Sabers and Saddles: the Second Regiment of United

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

X^Sno7>\ 3V N,.AT^,7,W

Form 10-300 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR STATE: (July 1969) NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Oklahoma COUNTY: NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES Choctaw INVENTORY - NOMINATION FORM FOR NPS USE ONLY ENTRY NUMBER DATE (Type all entries complete applicable sections) /^/^J^<D<D09 9/3 ?/?< .:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:+:.:.:.:.:.:.^^^^££:£:::::::£:::£:::£:$£# COMMON: Fort Towson AND/OR HISTORIC: Cantonment Towson x^sno7>\ nilIllllililfc STREET AND NUMBER: A\X [fFrFn/FF] V^N / »_/ ' * tt/L| v L. Lj \ - ' \ I m. northeast of the town of /CO/ *..,..,/ «« m-»n \^\ CITY OR TOWN: J Fort Towson \3V N,.AT^,7,W fei STATE CQDE coif*^! REGJST^'^ ^"v CODE Oklahoma 55 6%i^taw J ^^^7 025 \'-'J-\'<'\'\'<'-:-Tfc''-''X''-''-''-'^:;:::;:::::Nif:^^:: ::^^::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::";-:':::^^-:; ^1'J 1 i^~.s ACCESSIBLE ts* CATEGORY OWNERSHIP ( Check One) TO THE PUBLIC E£] District CD Building Ixl Public Public Acquisition: D Occupied Yes: O K=n . , . , Kl Restricted n Site CD Structure CD Private CD '" Process Kl Unoccupied ' ' CD Object D Both n Being Cons iucieuidered ri |i PreservationD * worki CD Unrestricted 1- in progress ' ' U PRESENT USE (Check One or More as Appropriate) E£] Agricultural | | Government | | Park CD Transportation CD Comments a: CD Commercial CD Industrial | | Private Residence CD Other fSoecih,) h- CD Educational CD Military CD Religious At present ruins are merely being protected. uo CD Entertainment 03 Museum [f; Scientific .................. :::::¥:¥£tt:W:W:¥:¥:¥:^^ ^ :|:;$S:j:S;:|:;:S|:|:;:i:|:;:|:;:;:|:i:|:i:S:H::^ OWNER'S NAME: _ _ 01 Lessee: Fee Owner: Oklahoma Historical Society Th<» K-frlrnafr-lrlf Foundation $ IT LU STREET AND NUMBER: 13 W Historical Building 3 CITY OR TOWN: STATE: CODE b Oklahoma City Oklahoma $5 COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS, ETC: COUNTY: Office of the County Clerk O STREET AND NUMBER: O O Choc taw County Courthouse Cl TY OR TOWN: STATE CODE * HUP-O . -

The Documentary History of the Campaign on the Niagara Frontier in 1814

Documentary History 9W ttl# ampatgn on tl?e lagara f rontier iMiaM. K«it*«l fisp the Luntfy« Lfluiil "'«'>.,-,.* -'-^*f-:, : THE DOCUMENTARY HISTORY OF THE CAMPAIGN ON THE - NIAGARA FRONTIER IN 1814. EDITED FOR THE LUNDTS LANE HISTORICAL SOCIETY BY CAPT. K. CRUIK8HANK. WELLAND PRINTBD AT THE THIBVNK OKKICB. F-5^0 15 21(f615 ' J7 V.I ^L //s : The Documentary History of the Campaign on the Niagara Frontier in 1814. LIEVT.COL. JOHN HARVEY TO Mkl^-iiE^, RIALL. (Most Beoret and Confidential.) Deputy Adjutant General's Office, Kingston, 28rd March, 1814. Sir,—Lieut. -General Drummond having had under his con- sideration your letter of the 10th of March, desirinjr to be informed of his general plan of defence as far as may be necessary for your guidance in directing the operations of the right division against the attempt which there is reason to expect will be made by the enemy on the Niagara frontier so soon as the season for operations commences, I have received the commands of the Lieut.-General to the following observations instructions to communicate you and y The Lieut. -General concurs with you as to the probability of the enemy's acting on the ofTensive as soon as the season permits. Having, unfortunately, no accurate information as to his plans of attack, general defensive arrangements can alone be suggested. It is highly probable that independent of the siege of Fort Niagara, or rather in combination with the atttick on that place, the enemy \vill invade the District of Niagara by the western road, and that he may at the same time land a force at Long Point and per- haps at Point Abino or Fort Erie. -

Florida Historical Quarterly FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY

The Florida Historical Quarterly FLORIDA HISTORICAL SOCIETY V OLUME XLV July 1966 - April 1967 CONTENTS OF VOLUME XLV Abernethy, Thomas P., The Formative Period in Alabama, 1815- 1828, reviewed, 180 Adams, Adam, book review by, 70 Agriculture and the Civil War, by Gates, reviewed, 68 Alachua County Historical Commission, 89, 196 Alexander, Charles C., book review by, 186 “American Seizure of Amelia Island,” by Richard G. Lowe, 18 Annual Meeting, Florida Historical Society May 5-7, 1966, 199 May 5-6, 1967, 434 Antiquities Commission, 321 Appalachicola Historical Society, 308 Arana, Luis R., book review by, 61 Atticus Greene Haygood, by Mann, reviewed, 185 Bailey, Kenneth K., Southern White Protestantism in the Twen- tieth Century, reviewed, 80 Barber, Willard F., book review by, 84 Baringer, William E., book review by, 182 Barry College, 314 Batista, Fulgencio, The Growth and Decline of the Cuban Repub- lic, reviewed, 82 Battle of Pensacola, March 9 to May 8, 1781; Spain’s Final Triumph Over Great Britain in the Gulf of Mexico, by Rush, reviewed, 412 Beals, Carlton, War Within a War: The Confederacy Against Itself, reviewed, 182 Bearss, Edwin C., “The Federal Expedition Against Saint Marks Ends at Natural Bridge,” 369 Beck, Earl R., On Teaching History in Colleges and Universities, reviewed, 432 Bennett, Charles E., “Early History of the Cross-Florida Barge Canal,” 132; “A Footnote on Rene Laudionniere,” 287; Papers, 437 Bigelow, Gordon E., Frontier Eden: The Literary Career of Mar- jorie Kinnan Rawlings, reviewed, 410 “Billy Bowlegs (Holata Micco) in the Second Seminole War” (Part I), 219; “Billy Bowlegs (Holata Micco) in the Civil War” (Part II), 391 “Bishop Michael J. -

Wildlife Habitat in Oklahoma Territory and the Chickasaw Nation, Circa 1870

W 2800.7 F293 no. T-17-P-1 6/04-12/07 c.1 FINAL PERFORMA1~CEREPORT OKL.AHOMA o "7JLDLIFE HABITAT IN OKLAHOMA TERRITORY AND THE CmCKASAW NATION, CIRCA 1870 . OKLAHOMA DEPARTMENT OF WILDLIFE CONSERVATION June 1, 2004 through December 31,2007 Grant Tide: Wildlife Habitat in Oklahoma Territory and the Chickasaw Nation, circa 1870 Principal Investiga!or: Bruce Hoagland . '. Abstract: Habitat loss is the greatest threat facing wildlife species. This project created a land cover map of Oklahoma using General Land Office plats circa 1871. Such maps provide both a snapshot of past habitat conditions and a baseline for comparison with the modern distribution of wildlife habitat. General Land Office plats were acquired from the Archives Division of the Oklahoma Department of Libraries, georeferenced and digitized. Plat features were categorized as hydrology, transportation, land cover, or settlement. Each of these categories were further subdivided. For example, land cover consisted of natural (i.e., grassland, forests, etc.) and agricultural (cultivated lands, orchards, etc.). A total of 1,348 plats were digitized and joined into a comprehensive map. Grassland (6.2 million hectares) was the most extensive land cover type, followed by forest-woodland (2.6 million hectares). A sawmill, two lime kilns, a sandstone quarry, and several stores are examples of settlement features encountered. Land in cultivation was 7,600 hectares, and several named ranches were present. Future studies should include comparisons between the 1870s map and modern data sources such as the Gap Analysis map in order to quantify habitat change. Introduction: Habitat loss is the greatest threat facing wildlife species. -

State of the Coronado National Forest

Douglas RANGER DISTRICT www.skyislandaction.org 3-1 State of the Coronado Forest DRAFT 11.05.08 DRAFT 11.05.08 State of the Coronado Forest 3-2 www.skyislandaction.org CHAPTER 3 Dragoon Ecosystem Management Area The Dragoon Mountains are located at the heart of development. Crossing Highway 80, one passes the Coronado National Forest. The Forest through another narrow strip of private land and encompasses 52,411 acres of the mountains in an area enters the BLM-managed San Pedro Riparian some 15 miles long by 6 miles wide. The Dragoon National Conservation Area. On the west side of the Ecosystem Management Area (EMA) is the smallest San Pedro River, the valley (mostly under private and on the Forest making it sensitive to activities state land jurisdiction) slopes up to the Whetstone happening both on the Forest and in lands Mountains, another Ecosystem Management Area of surrounding the Forest. Elevations range from the Coronado National Forest. approximately 4,700 feet to 7,519 feet at the summit of Due to the pattern of ecological damage and Mount Glenn. (See Figure 3.1 for an overview map of unmanaged visitor use in the Dragoons, we propose the Dragoon Ecosystem Management Area.) the area be divided into multiple management units ( The Dragoons are approximately sixty miles 3.2) with a strong focus on changing management in southeast of Tucson and thirty-five miles northeast of the Dragoon Westside Management Area (DWMA). Sierra Vista. Land adjacent to the western boundary of In order to limit overall impacts on the Westside, a the Management Area is privately owned and remains visitor permit system with a cap on daily visitor relatively remote and sparsely roaded compared to the numbers is recommended. -

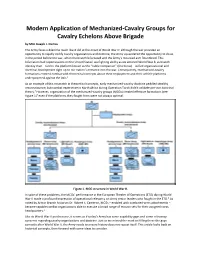

Modern Application of Mechanized-Cavalry Groups for Cavalry Echelons Above Brigade by MAJ Joseph J

Modern Application of Mechanized-Cavalry Groups for Cavalry Echelons Above Brigade by MAJ Joseph J. Dumas The Army faces a dilemma much like it did at the onset of World War II: although the war provided an opportunity to rapidly codify cavalry organizations and doctrine, the Army squandered the opportunity to do so in the period before the war, when the branch bifurcated and the Army’s mounted arm floundered. This bifurcation had repercussions on the United States’ warfighting ability as we entered World War II, as branch identity then – tied to the platform known as the “noble companion” (the horse) – stifled organizational and doctrinal development right up to our nation’s entrance into the war. Consequently, mechanized-cavalry formations entered combat with theoretical concepts about their employment and their vehicle platforms underpowered against the Axis.1 As an example of this mismatch in theoretical concepts, early mechanized-cavalry doctrine peddled stealthy reconnaissance, but combat experience in North Africa during Operation Torch didn’t validate pre-war doctrinal theory.2 However, organization of the mechanized-cavalry groups (MCGs) created effective formations (see Figure 1)3 even if the platforms they fought from were not always optimal. Figure 1. MCG structure in World War II. In spite of these problems, the MCGs’ performance in the European Theater of Operations (ETO) during World War II made a profound impression of operational relevancy on Army senior leaders who fought in the ETO.4 As noted by Armor Branch historian Dr. Robert S. Cameron, MCGs – enabled with combined-arms attachments – became capable combat organizations able to execute a broad range of mission sets for their assigned corps headquarters.5 Like its World War II predecessor, it seems as if today’s Army has some capability gaps and some relevancy concerns regarding cavalry organizations and doctrine. -

Before the Line Volume Iii Caddo Indians: the Final Years

BEFORE THE LINE VOLUME III CADDO INDIANS: THE FINAL YEARS BEFORE THE LINE VOLUME III CADDO INDIANS: THE FINAL YEARS Jim Tiller Copyright © 2013 by Jim Tiller All rights reserved Bound versions of this book have been deposited at the following locations: Louisiana State University, Shreveport (Shreveport, Louisiana) Sam Houston State University (Huntsville, Texas) Stephen F. Austin State University (Nacogdoches, Texas) Texas A&M University (College Station, Texas) Texas General Land Office (Archives and Records) (Austin, Texas) Texas State Library (Austin, Texas) University of North Texas (Denton, Texas) University of Texas at Austin (Austin, Texas) To view a pdf of selected pages of this and other works by Jim Tiller, see: http://library.shsu.edu > Digital Collection > search for: Jim Tiller Electronic versions of Vol. I, II and III as well as a limited number of bound sets of the Before the Line series are available from: The Director, Newton Gresham Library, Sam Houston State University, PO Box 2281 (1830 Bobby K. Marks Drive), Huntsville, Texas 77341 Phone: 936-294-1613 Design and production by Nancy T. Tiller The text typefaces are Adobe Caslon Pro and Myriad Pro ISBN 978-0-9633100-6-4 iv For the People of the Caddo Nation Also by Jim Tiller Our American Adventure: The History of a Pioneer East Texas Family, 1657-1967(2008) (with Albert Wayne Tiller) Named Best Family History Book by a Non-Professional Genealogist for 2008 by the Texas State Genealogical Society Before the Line Volume I An Annotated Atlas of International Boundaries and Republic of Texas Administrative Units Along the Sabine River-Caddo Lake Borderland, 1803-1841 (2010) Before the Line Volume II Letters From the Red River, 1809-1842 (2012) Jehiel Brooks and the Grappe Reservation: The Archival Record (working manuscript) vi CONTENTS Preface . -

Early Days at Fort Brooke

Sunland Tribune Volume 1 Article 2 1974 Early Days at Fort Brooke George Mercer Brooke Jr. Virginia Military Institute Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/sunlandtribune Recommended Citation Brooke, George Mercer Jr. (1974) "Early Days at Fort Brooke," Sunland Tribune: Vol. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/sunlandtribune/vol1/iss1/2 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Sunland Tribune by an authorized editor of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. (DUO\'D\VDW)RUW%URRNH By COL. GEORGE MERCER BROOKE, JR. Professor of History Virginia Military Institute, Lexington, Va. On 5 November 1823, the Adjutant General in Washington ordered Lieutenant Colonel George Mercer Brooke of the Fourth Infantry to take four companies from Cantonment Clinch near Pensacola to Tampa Bay for the purpose of building a military post. Exactly three months later, Brooke reported from the Tampa Bay area that he had arrived and work on the post was under way. A study of this troop movement and the construction of the cantonment later called Fort Brooke gives some insight into the problems the army faced one hundred and fifty years ago. At that time the population of the country was only ten million and the immigration flood of the nineteenth century was as yet only a trickle. The population was predominantly rural, only seven per cent living in urban areas. The railroad era lay in the future. Missouri had just recently been admitted as the twenty-fourth state after a portentous struggle on the slavery issue, and the country was laboring to recover from the Panic of 1819 induced in large part by overspeculation in land. -

The Civil War and Reconstruction in Indian Territory

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and University of Nebraska Press Chapters 2015 The iC vil War and Reconstruction in Indian Territory Bradley R. Clampitt Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/unpresssamples Clampitt, Bradley R., "The ivC il War and Reconstruction in Indian Territory" (2015). University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters. 311. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/unpresssamples/311 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Nebraska Press at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Nebraska Press -- Sample Books and Chapters by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. The Civil War and Reconstruction in Indian Territory Buy the Book Buy the Book The Civil War and Reconstruction in Indian Territory Edited and with an introduction by Bradley R. Clampitt University of Nebraska Press Lincoln and London Buy the Book © 2015 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska A portion of the introduction originally appeared as “ ‘For Our Own Safety and Welfare’: What the Civil War Meant in Indian Territory,” by Bradley R. Clampitt, in Main Street Oklahoma: Stories of Twentieth- Century America edited by Linda W. Reese and Patricia Loughlin (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2013), © 2013 by the University of Oklahoma Press. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved Manufactured in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data The Civil War and Reconstruction in Indian Territory / Edited and with an introduction by Bradley R. -

Call the Seminole Tribune Hamilton, MT

Seminole Grass Dancers honored at Fair, see special section. Tribe gives Broward Commisioners framed Seminole Heritage Celebration poster. Shark attack, page 10. Bulk Rate U.S. Postage Paid Lake Placid FL Permit No. 128 TheSEMINOLE TRIBUNE “Voice of the Unconquered” 50c www.seminoletribe.com Volume XXI Number 3 March 3, 2000 Hunting Gator By Colin Kenny BIG CYPRESS — Jay Young has handled many a gator on his father’s alligator farm for the last 13 years. He has done it all, from wrestling the surly reptiles in front of gaping spectators and rais- ing the mega-lizards from birth to nursing some really sickly saurians back Colorado Gator Farmers to health. Unlike many alligator wrestlers, though, Jay has yet to have a close encounter with the scaly beastie in its natural habitat. But then again, one doesn’t encounter too many wild gators — in Colorado. As the main alligator wrangler out west, it was Jay who got the call to bring one to New Mexico last November. The caller was Seminole Chief Jim Billie who wanted to bring a live gator on stage with him at the Native American Music Awards (NAMA) in Albuquerque, N.M. A few hours after the Chief called, Jay, 25, and Paul Wertz, 28, of Colorado Gators were carry- ing an eight-foot gator to the stage while the Chief performed his signature song “Big Alligator” to a frenzied, sold out Popejoy Hall crowd at the University of New Mexico. Chief Billie returned the favor last week by having the two young men, Jay’s pregnant wife, Cathy, and Paul’s fiancée, Fawn, flown to Big Cypress, Florida for some real live gator huntin.’ Chief Billie — along with experienced gator-men Joe Don Billie, Danny Johns, and Roscoe Coon — took the Coloradoans down Snake Road to a spot near the Seminole/Miccosukee reservation line where a fairly large gator had been spotted ear- lier on the bank of the canal. -

The African American Soldier at Fort Huachuca, Arizona, 1892-1946

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Faculty Publications Anthropology, Department of 2-2001 The African American Soldier At Fort Huachuca, Arizona, 1892-1946 Steven D. Smith University of South Carolina - Columbia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/anth_facpub Part of the Anthropology Commons Publication Info Published in 2001. © 2001, University of South Carolina--South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology This Book is brought to you by the Anthropology, Department of at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE AFRICAN AMERICAN SOLDIER AT FORT HUACHUCA, ARIZONA, 1892-1946 The U.S Army Fort Huachuca, Arizona, And the Center of Expertise for Preservation of Structures and Buildings U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, Seattle District Seattle, Washington THE AFRICAN AMERICAN SOLDIER AT FORT HUACHUCA, ARIZONA, 1892-1946 By Steven D. Smith South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology University of South Carolina Prepared For: U.S. Army Fort Huachuca, Arizona And the The Center of Expertise for Preservation of Historic Structures & Buildings, U.S. Army Corps of Engineer, Seattle District Under Contract No. DACW67-00-P-4028 February 2001 ABSTRACT This study examines the history of African American soldiers at Fort Huachuca, Arizona from 1892 until 1946. It was during this period that U.S. Army policy required that African Americans serve in separate military units from white soldiers. All four of the United States Congressionally mandated all-black units were stationed at Fort Huachuca during this period, beginning with the 24th Infantry and following in chronological order; the 9th Cavalry, the 10th Cavalry, and the 25th Infantry. -

Zachary Taylor 1 Zachary Taylor

Zachary Taylor 1 Zachary Taylor Zachary Taylor 12th President of the United States In office [1] March 4, 1849 – July 9, 1850 Vice President Millard Fillmore Preceded by James K. Polk Succeeded by Millard Fillmore Born November 24, 1784Barboursville, Virginia Died July 9, 1850 (aged 65)Washington, D.C. Nationality American Political party Whig Spouse(s) Margaret Smith Taylor Children Ann Mackall Taylor Sarah Knox Taylor Octavia Pannill Taylor Margaret Smith Taylor Mary Elizabeth (Taylor) Bliss Richard Taylor Occupation Soldier (General) Religion Episcopal Signature Military service Nickname(s) Old Rough and Ready Allegiance United States of America Service/branch United States Army Years of service 1808–1848 Rank Major General Zachary Taylor 2 Battles/wars War of 1812 Black Hawk War Second Seminole War Mexican–American War *Battle of Monterrey *Battle of Buena Vista Zachary Taylor (November 24, 1784 – July 9, 1850) was the 12th President of the United States (1849-1850) and an American military leader. Initially uninterested in politics, Taylor nonetheless ran as a Whig in the 1848 presidential election, defeating Lewis Cass. Taylor was the last President to hold slaves while in office, and the last Whig to win a presidential election. Known as "Old Rough and Ready," Taylor had a forty-year military career in the United States Army, serving in the War of 1812, the Black Hawk War, and the Second Seminole War. He achieved fame leading American troops to victory in the Battle of Palo Alto and the Battle of Monterrey during the Mexican–American War. As president, Taylor angered many Southerners by taking a moderate stance on the issue of slavery.