State of the Coronado National Forest

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Section 9-Sierra Vista Subbasin of the Upper San Pedro Basin, Arizona

Section 9.—Conceptual Understanding and Groundwater Quality of the Basin-Fill Aquifer in the Sierra Vista Subbasin of the Upper San Pedro Basin, Arizona By David W. Anning and James M. Leenhouts in Conceptual Understanding and Groundwater Quality of Selected Basin- Fill Aquifers in the Southwestern United States Edited by Susan A. Thiros, Laura M. Bexfield, David W. Anning, and Jena M. Huntington National Water-Quality Assessment Program Professional Paper 1781 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey ii Contents Basin Overview .........................................................................................................................................145 Water Development History .....................................................................................................................147 Hydrogeology .............................................................................................................................................148 Conceptual Understanding of the Groundwater Flow System ...........................................................149 Water Budget ....................................................................................................................................149 Groundwater Movement .................................................................................................................152 Effects of Natural and Human Factors on Groundwater Quality ......................................................157 Summary......................................................................................................................................................160 -

Coronado National Forest Draft Land and Resource Management Plan I Contents

United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service Coronado National Forest Southwestern Region Draft Land and Resource MB-R3-05-7 October 2013 Management Plan Cochise, Graham, Pima, Pinal, and Santa Cruz Counties, Arizona, and Hidalgo County, New Mexico The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TTY). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Front cover photos (clockwise from upper left): Meadow Valley in the Huachuca Ecosystem Management Area; saguaros in the Galiuro Mountains; deer herd; aspen on Mt. Lemmon; Riggs Lake; Dragoon Mountains; Santa Rita Mountains “sky island”; San Rafael grasslands; historic building in Cave Creek Canyon; golden columbine flowers; and camping at Rose Canyon Campground. Printed on recycled paper • October 2013 Draft Land and Resource Management Plan Coronado National Forest Cochise, Graham, Pima, Pinal, and Santa Cruz Counties, Arizona Hidalgo County, New Mexico Responsible Official: Regional Forester Southwestern Region 333 Broadway Boulevard, SE Albuquerque, NM 87102 (505) 842-3292 For Information Contact: Forest Planner Coronado National Forest 300 West Congress, FB 42 Tucson, AZ 85701 (520) 388-8300 TTY 711 [email protected] Contents Chapter 1. -

The Grand Duke Constantine's Regiment of Cuirassiers of The

Johann Georg Paul Fischer (Hanover 1786 - London 1875) The Grand Duke Constantine’s Regiment of Cuirassiers of the Imperial Russian Army in 1806 signed and dated ‘Johann Paul Fischer fit 1815’ (lower left); dated 1815 (on the reverse); the mount inscribed with title and dated 1806 watercolour over pencil on paper, with pen and ink 20.5 x 29 cm (8 x 11½ in) This work by Johann Georg Paul Fischer is one of a series of twelve watercolours depicting soldiers of the various armies involved in the Napoleonic Wars, a series of conflicts which took place between 1803 and 1815, when Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821) was defeated at the Battle of Waterloo. The series is a variation of a similar set executed slightly earlier, held in the Royal Collection, and which was probably purchased by, or presented to, the Prince Regent. In this work, Fischer depicts various elements of the Russian army. On the left hand side, the Imperial Guard stride forward in unison, each figure looking gruff and determined. They are all tall, broad and strong and as a collective mass they appear very imposing. Even the drummer, who marches in front, looks battle-hardened and commanding. On the right-hand side, a cuirassier sits atop his magnificent steed and there appear to be further cavalry soldiers behind him. There is a swell of purposeful movement in the work, which creates an impressive image of military power. The Russian cuirassiers were part of the heavy cavalry and were elite troops as their ranks were filled up with the best soldiers selected from dragoon, uhlan, jager and hussar regiments. -

The Anglo-Portuguese Army, September 1810

The Anglo-Portuguese Army September 1810 Commanding General: Viscount Wellington Artillery Commander: Brigadier-General Howorth Engineer Commander: Lieutenant Colonel Fletcher Quartermaster Gen.: Colonel Murray Infantry 1st Division: Lieutenant-General Spencer Brigade: Stopford 1/Coldstream Guard Regiment (24/790) 1/Scots Fusilier Guard Regiment (26/791) 5/60th Foot Regiment (1 coy)(2/51) Brigade: Lord Blantyre 2/24th Foot Regiment (30/338) 2/42nd Foot Regiment (23/391) 1/61st Foot Regiment (36/648) 5/60th Foot Regiment (1 coy)(3/47) Brigade: 1st KGL Line Battalion (28/510) 2nd KGL Line Battalion (31/453) 5th KGL Line Battalion (30/460) 7th KGL Line Battalion (24/429) Det. KGL Light Battalions (6/90) Brigade: Pakenham 1/7th Foot Regiment (26/843) 1/79th Foot Regiment (38/885) 2nd Division: Major-General Hill Brigade: W. Stewart 1/3rd Foot Regiment (32/826) 2/31st Foot Regiment (27/384) 2/48th Foot Regiment (27/454) 2/66th Foot Regiment (30/433) 5/60th Foot Regiment (1 co)(1/33) Brigade: Inglis 29th Foot Regiment (31/430) 1/48th Foot Regiment (32/519) 1/57th Foot Regiment (28/727) 5/60th Foot Regiment (1 co)(1/50) Brigade: C. Crawfurd 2/28th Foot Regiment (32/522) 2/34th Foot Regiment (36/617) 2/39th Foot Regiment (27/394) 5/60th Foot Regiment (1 co)(2/42) Portuguese Division: Brigade: Campbell 4th Portuguese Line Regiment (2)(1,164) 10th Portuguese Line Regiment (2)(1,086) Brigade: Fonseca 2nd Portuguese Line Regiment (2)(1,317) 14th Portuguese Line Regiment (2)(1,373) 3rd Division: Major General Picton Brigade: Mackinnon 1/45th Foot Regiment (35/560) 1 74th Foot Regiment (38/456) 1/88th Foot Regiment (40/679) Brigade: Lightburne 2/5th Foot Regiment (31/464) 2/83rd Foot Regiment (43/461) 5/90th Foot Regiment (3 coys)(16/145) Portuguese Brigade: Champlemond (Harvey) 9th Portuguese Line Regiment (2)(1,234) 21st Portuguese Line Regiment (1)(541) 4th Division: L.Cole Brigade: A. -

Deaths, Desertions, & Stations in the British Army 1811

Deaths, Desertions and Stations of the British Army l8ll Deaths Desertions Station lst Life Guard Regiment - - England 2nd Life Guard Regiment - - England Royal Regiment of Horse Guards 6 7 England lst Dragoon Guard Regiment 9 l5 Ireland 2nd Dragoon Guard Regiment l2 22 England 3rd Dragoon Guard Regiment 66 9 Eng. & Portugal 4th Dragoon Guard Regiment 79 l6 ditto 5th Dragoon Guard Regiment 2l ll ditto 6th Dragoon Guard Regiment l3 22 Scotland 7th Dragoon Guard Regiment 9 l6 England lst Dragoon Regiment 56 l Eng. & Portugal 2nd Dragoon Regiment ll l4 England 3rd Dragoon Regiment 4l l4 Eng. & Portugal 4th Dragoon Regiment 39 5 ditto 5th Dragoon Regiment unk unk 6th Dragoon Regiment l6 42 Ireland 7th Light Dragoon Regiment l9 30 Ireland 8th Light Dragoon Regiment 26 - Bengal 9th Light Dragoon Regiment 47 34 Eng. & Portugal l0th Light Dragoon Regiment l3 l9 England llth Light Dragoon Regiment 68 l7 Eng. & Portugal l2th Light Dragoon Regiment 52 l4 Eng. & Portugal l3th Light Dragoon Regiment 99 2 Eng. & Portugal l4th Light Dragoon Regiment 49 9 Eng. & Portugal l5th Light Dragoon Regiment l6 l8 England l6th Light Dragoon Regiment 48 l0 Eng. & Portugal l7th Light Dragoon Regiment 40 0 Bombay, India l8th Light Dragoon Regiment l2 26 England l9th Light Dragoon Regiment 9 44 Ireland 20th Light Dragoon Regiment 27 8 Sicily 2lst Light Dragoon Regiment l3 - Cape of Good Hope 22nd Light Dragoon Regiment 55 - Madras, India 23rd Light Dragoon Regiment 7 l9 England 24th Light Dragoon Regiment 24 - Bengal, India 25th Light Dragoon Regiment 47 - Madras, India l/lst Foot Guard Regiment l5 40 England 2/lst Foot Guard Regiment 8l 20 England 3/lst Foot Guard Regiment 20 7 Cadiz l/Coldstream Foot Guard Regiment 73 l Portugal 2/Coldstream Foot Guard Regiment 45 38 England l/3rd Foot Guard Regiment 64 l Portugal 2/3rd Foot Guard Regiment 64 l2 England Royal Waggon Train 42 ll Eng. -

The London Gazette, June 3, 1910

3884 THE LONDON GAZETTE, JUNE 3, 1910. CAVALRY. IQth (Queen Alexandra's Own Royal) Hussars, Lieutenant Guy Bonham-Carter is seconded for 2nd Life Guards, The undermentioned Lieutenants service under the Colonial Office. Dated llth to be Captains. Dated 2nd May, 1910 :— May, 1910. Charles N. Newton, vice S. B. B. Dyer, D.S.O., retired. 20th Hussars, Lieutenant Robert G. Berwick is seconded for service with the Northern Cavalry The Honourable Algernon H. Strutt, vice Depot. Dated 21st April, 1910. C. Champion de Crespigny, D.8.O., retired. Second Lieutenant Wilfrid H. M. Micholls 1st (King's) Dragoon Guards, Lieutenant Samuel to be Lieuteuant, vice R. G. Berwick. Dated E. Harvey is placed temporarily on the Half- 21st April, 1910. pay List on account of ill-health. Dated 13th May, 1910. ROYAL REGIMENT OF ARTILLERY. 2nd Dragoon Guards (Queen's Bays}, Lieutenant Royal Horse and Royal Field Artillery, Lieutenant- David H. Evaus resigns his Commission. Dated Colonel Walter E. Kerrich, Indian Ordnance 4th June, 1910. Department, retires on an Indian pension. 4th (Royal Irish) Dragoon Guards, Second Lieu- Dated 2nd June, 1910. tenant Oswald Beddall Sanderson, from East The undermentioned Captains to be Majors. Riding- of Yorkshire Yeomanry, to be Second Dated 28th May, 1910 :— Lieutenant (on probation), in succession to George T. Mair, D.S.O., vice L. H. D. Lieutenant R. W. Oppenheim, placed tem- Broughton, retired. porarily on the Half-pay List on account of ill-health. Dated 4th June, 1910. Arthur C. Edwards, vice G. T. Mair, D.S.O., seconded. 2nd Dragoons (Royal Scots Greys), Second Lieu- Supernumerary Captain Charles A. -

![7 Armoured Division (1941-42)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/4788/7-armoured-division-1941-42-1304788.webp)

7 Armoured Division (1941-42)]

3 September 2020 [7 ARMOURED DIVISION (1941-42)] th 7 Armoured Division (1) Headquarters, 7th Armoured Division 4th Armoured Brigade (2) Headquarters, 4th Armoured Brigade & Signal Section 4th Royal Tank Regiment (3) 5th Royal Tank Regiment (3) 7th Royal Tank Regiment (4) 7th Armoured Brigade (5) Headquarters, 7th Armoured Brigade & Signal Section 2nd Royal Tank Regiment 7th Support Group (6) Headquarters, 7th Support Group & Signal Section 1st Bn. The King’s Royal Rifle Corps 2nd Bn. The Rifle Brigade (Prince Consort’s Own) 3rd Regiment, Royal Horse Artillery 4th Regiment, Royal Horse Artillery 1st Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Artillery Divisional Troops 11th Hussars (Prince Albert’s Own) (7) 4th Field Squadron, Royal Engineers (8) 143rd Field Park Squadron, Royal Engineers (8) 7th Armoured Divisional Signals, Royal Corps of Signals ©www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk Page 1 3 September 2020 [7 ARMOURED DIVISION (1941-42)] NOTES: 1. This was a regular army division stationed in Egypt. It had been formed as the Mobile Division in September 1938, as a result of the raised tension caused by the Munich Crisis. Initially called the ‘Matruh Mobile Force’, it was founded by Major General P. C. S. HOBART. This is the Order of Battle for the division on 15 May 1941. This was the date of the start of Operation Brevity, the operation to reach Tobruk The division was under command of Headquarters, British Troops in Egypt until 16 May 1941. On that date, it came under command of Headquarters, Western Desert Force (W.D.F.). It remained under command of W.D.F. -

Coronado National Forest Potential Wilderness Area Evaluation Report

United States Department of Agriculture Coronado National Forest Potential Wilderness Area Evaluation Report Forest Service Southwestern Region Coronado National Forest July 2017 Potential Wilderness Area Evaluation Report In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-9992. Submit your completed form or letter to USDA by: (1) mail: U.S. -

Exploring the Dragoons Land of Cochise PLUS Prescott‘S Mail Trail West Clear Creek Magic Contents August 2007 38 36 32 22 16

Conquer Fear at an Outdoors Camp for Women AUGUST 2007 Exploring the Dragoons Land of Cochise PLUS Prescott‘s Mail Trail West Clear Creek Magic 8 Chasing Cochise History lingers among the rocks in the search for the Dragoon Mountains campsites of the great Apache chief. BY PETER ALESHIRE PHOTOGRAPHS BY RANDY PRENTICE online arizonahighways.com Need some help when it comes to Arizona august 2007 history? Allow it to repeat itself this month 16 Why Are They with some of the top-rated trips in our “10 Trying to Kill Me? Great History Trips Guide.” Go online for this Writer rides Prescott's historic Mail Trail. and more at www.arizonahighways.com. BY ROGER NAYLOR PHOTOGRAPHS BY HUMOR Our writer explores his own personal DON B. AND RYAN B. STEVENSON history as he recalls his first father-and-son chat. WEEKEND GETAWAY Explore some real "hot 22 Wet Wizard spots" in Tombstone and the Dragoon Mountains. Water makes magic in West Clear Creek. BY STEVE BRUNO EXPERIENCE ARIZONA Plan your Arizona getaway with our events calendar. 32 ‘Profitless’ Splendor contents Lt. Ives' epic journey upriver to the Grand Canyon yielded stirring adventure and a foolish prediction. Photographic Prints Available BY GREGORY M CNAMEE n Prints of some photographs are available for purchase, as designated in captions. To order, call toll-free (866) 962-1191 or visit 36 Troubadours of Summer Cicadas inspire myths and mischief. www.magazineprints.com. BY CARRIE M. MINER PHOTOGRAPHS BY MARTY CORDANO 38 Learning to Lean Back Outdoors woman camp in the Bradshaw Mountains reveals the benefits of fear. -

Second Day -- Ap Ril 6, 1959

Southeastern Arizona-Trip V-2 GENERAL GEOLOGY OF SOUTHEASTERN ARIZONA TRIP V, ROAD LOG (C ontinue d) Second Day -- Ap ril 6, 1959 Leaders: E. B. Mayo and W. D. Pye Driving Distance: 225. 7 miles Logged Distance: 216. 9 miles Starting Time : 7:00 A. M. General Statement: The route leads northward, along the axis of Sulphur Spring s Valley to Elfrida. From Elfrida the course is westward to the southe rn Dragoon Mountains and the old mining camps of Gleeson and Courtland. It will then continue northward along Sulphur Spring s Valley, finally turning eastward to ascend the out wash apron of the Chiricahua Mountains. The route will then head northward and northeastward over Apache Pas s, and on to Bowie and State Highway 86. From Bowie the route is southwestward to Willcox, then along the no rthern margin of Willcox Playa. It ascends southwestward past the northern edge of the Red Bird Hills, pas ses betwe en the Gunnison Hills and Steele Hill s, crosses the Little Dragoon Mountains via Texas Canyon, and de scends to Benson on the San Pedro River. Beyond Benson the highway asc ends we stward betw een the Whetstone Mountain s on the south and the Rincons on the north to Mountain View, and on to Tucson. The party will see: (1) the thrust blocks, intrusions and abandoned mining camps of the southern Dragoon Mountains; (2) some of the volcanic rocks of the northern Chiricahua Mountains ; (3) the Precam brian granite and the Cretaceous and Paleozoic sections in Apache Pass; (4) Willcox Playa, lowe st part of Sulphur Sp ring s Valley; (5) the Paleozoic section of the Gunnison Hills, and the young er Precambrian Apache and Paleozoic sequences of the Little Dragoon Mountains; (6) the porphyritic granite of Texas Canyon; and (7) the steeply-dipping Miocene (?) Pantano beds west of Benson. -

Ambient Groundwater Quality of Tlie Douglas Basin: an ADEQ 1995-1996 Baseline Study

Ambient Groundwater Quality of tlie Douglas Basin: An ADEQ 1995-1996 Baseline Study I. Introduction »Ragstaff The Douglas Groundwater Basin (DGB) is located in southeastern Arizona (Figure 1). It is a picturesque broad alluvial valley surrounded by rugged mountain ranges. This factsheet is based on a study conducted in 1995- 1996 by the Arizona Department of Enviroimiental Quality (ADEQ) and Douglas summarizes a comprehensive regional Groundwater groundwater quality report (1). Basin The DGB was chosen for study for the following reasons: • Residents predominantly rely upon groundwater for their water needs. • There is a history of management decrees designed to increase groundwater sustainability (2). • The basin extends into Mexico, making groundwater issues an international concern. II. Background The DGB consists of the southern portion of the Sulphur Springs Valley, a northwest-southeast trending trough that extends through southeastern Arizona into Mexico. Covering 950 square miles, the DGB is roughly 15 miles wide and 35 miles long. The boundaries of the DGB include the Swisshelm (Figure 2), Pedregosa, and Perilla Mountains to the east, the Mule and Dragoon Mountains to the west, and a series of small ridges and buttes to * AguaPrieta the north (Figure 1). Although the Mexico DGB extends south hydrologically into Figure 1. Infrared satellite image of the Douglas Groundwater Basin (DGB) taken in June, 1993. Mexico, the international border serves Irrigated farmland is shown in bright red in the central parts of the basin, grasslands and mountain as the southern groundwater divide for areas appear in both blue and brown. The inset map shows the location of the DGB within Arizona. -

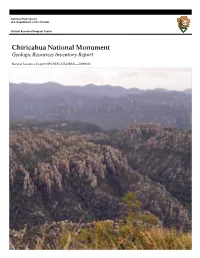

Chiricahua National Monument Geologic Resources Inventory Report

National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior Natural Resource Program Center Chiricahua National Monument Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR—2009/081 THIS PAGE: Close up of the many rhyolitic hoodoos within the Monument ON THE COVER: Scenic vista in Chiricahua NM NPS Photos by: Ron Kerbo Chiricahua National Monument Geologic Resources Inventory Report Natural Resource Report NPS/NRPC/GRD/NRR—2009/081 Geologic Resources Division Natural Resource Program Center P.O. Box 25287 Denver, Colorado 80225 June 2009 U.S. Department of the Interior National Park Service Natural Resource Program Center Denver, Colorado The Natural Resource Publication series addresses natural resource topics that are of interest and applicability to a broad readership in the National Park Service and to others in the management of natural resources, including the scientific community, the public, and the NPS conservation and environmental constituencies. Manuscripts are peer-reviewed to ensure that the information is scientifically credible, technically accurate, appropriately written for the intended audience, and is designed and published in a professional manner. Natural Resource Reports are the designated medium for disseminating high priority, current natural resource management information with managerial application. The series targets a general, diverse audience, and may contain NPS policy considerations or address sensitive issues of management applicability. Examples of the diverse array of reports published in this series include vital signs monitoring plans; "how to" resource management papers; proceedings of resource management workshops or conferences; annual reports of resource programs or divisions of the Natural Resource Program Center; resource action plans; fact sheets; and regularly-published newsletters.