Coronado National Forest Draft Land and Resource Management Plan I Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chiricahua Leopard Frog (Rana Chiricahuensis)

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service Chiricahua Leopard Frog (Rana chiricahuensis) Final Recovery Plan April 2007 CHIRICAHUA LEOPARD FROG (Rana chiricahuensis) RECOVERY PLAN Southwest Region U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Albuquerque, New Mexico DISCLAIMER Recovery plans delineate reasonable actions that are believed to be required to recover and/or protect listed species. Plans are published by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and are sometimes prepared with the assistance of recovery teams, contractors, state agencies, and others. Objectives will be attained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views nor the official positions or approval of any individuals or agencies involved in the plan formulation, other than the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. They represent the official position of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service only after they have been signed by the Regional Director, or Director, as approved. Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in species status, and the completion of recovery tasks. Literature citation of this document should read as follows: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2007. Chiricahua Leopard Frog (Rana chiricahuensis) Recovery Plan. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Southwest Region, Albuquerque, NM. 149 pp. + Appendices A-M. Additional copies may be obtained from: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Arizona Ecological Services Field Office Southwest Region 2321 West Royal Palm Road, Suite 103 500 Gold Avenue, S.W. -

Section 9-Sierra Vista Subbasin of the Upper San Pedro Basin, Arizona

Section 9.—Conceptual Understanding and Groundwater Quality of the Basin-Fill Aquifer in the Sierra Vista Subbasin of the Upper San Pedro Basin, Arizona By David W. Anning and James M. Leenhouts in Conceptual Understanding and Groundwater Quality of Selected Basin- Fill Aquifers in the Southwestern United States Edited by Susan A. Thiros, Laura M. Bexfield, David W. Anning, and Jena M. Huntington National Water-Quality Assessment Program Professional Paper 1781 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey ii Contents Basin Overview .........................................................................................................................................145 Water Development History .....................................................................................................................147 Hydrogeology .............................................................................................................................................148 Conceptual Understanding of the Groundwater Flow System ...........................................................149 Water Budget ....................................................................................................................................149 Groundwater Movement .................................................................................................................152 Effects of Natural and Human Factors on Groundwater Quality ......................................................157 Summary......................................................................................................................................................160 -

State of the Coronado National Forest

Douglas RANGER DISTRICT www.skyislandaction.org 3-1 State of the Coronado Forest DRAFT 11.05.08 DRAFT 11.05.08 State of the Coronado Forest 3-2 www.skyislandaction.org CHAPTER 3 Dragoon Ecosystem Management Area The Dragoon Mountains are located at the heart of development. Crossing Highway 80, one passes the Coronado National Forest. The Forest through another narrow strip of private land and encompasses 52,411 acres of the mountains in an area enters the BLM-managed San Pedro Riparian some 15 miles long by 6 miles wide. The Dragoon National Conservation Area. On the west side of the Ecosystem Management Area (EMA) is the smallest San Pedro River, the valley (mostly under private and on the Forest making it sensitive to activities state land jurisdiction) slopes up to the Whetstone happening both on the Forest and in lands Mountains, another Ecosystem Management Area of surrounding the Forest. Elevations range from the Coronado National Forest. approximately 4,700 feet to 7,519 feet at the summit of Due to the pattern of ecological damage and Mount Glenn. (See Figure 3.1 for an overview map of unmanaged visitor use in the Dragoons, we propose the Dragoon Ecosystem Management Area.) the area be divided into multiple management units ( The Dragoons are approximately sixty miles 3.2) with a strong focus on changing management in southeast of Tucson and thirty-five miles northeast of the Dragoon Westside Management Area (DWMA). Sierra Vista. Land adjacent to the western boundary of In order to limit overall impacts on the Westside, a the Management Area is privately owned and remains visitor permit system with a cap on daily visitor relatively remote and sparsely roaded compared to the numbers is recommended. -

Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; 12-Month Findings on Petitions

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 10/06/2016 and available online at https://federalregister.gov/d/2016-24142, and on FDsys.gov DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 17 [4500090022] Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; 12-Month Findings on Petitions To List 10 Species as Endangered or Threatened Species AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior. ACTION: Notice of 12-month petition findings. SUMMARY: We, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), announce 12-month findings on petitions to list 10 species as endangered or threatened species under the Endangered Species Act of 1973, as amended (Act). After a review of the best available scientific and commercial information, we find that listing the Huachuca-Canelo population of the Arizona treefrog, the Arkansas darter, black mudalia, Highlands tiger beetle, Dichanthelium (=panicum) hirstii (Hirst Brothers’ panic grass), two Kentucky cave beetles (Louisville cave beetle and Tatum Cave beetle), relict leopard frog, sicklefin redhorse sucker, and Stephan’s riffle beetle is not warranted at this time. However, we ask the public to submit to us at any time any new information that becomes available concerning the stressors to any of the 10 species listed above or their habitats. DATES: The findings announced in this document were made on [INSERT DATE OF FEDERAL REGISTER PUBLICATION]. ADDRESSES: Detailed descriptions of the basis for each of these findings are available on the Internet at 1 http://www.regulations.gov -

Draft Coronado Revised Plan

Coronado National United States Forest Department of Agriculture Forest Draft Land and Service Resource Management August 2011 Plan The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its programs and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sexual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW, Washington, DC 20250-9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TTY). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Printed on recycled paper – Month and Year Draft Land and Resource Management Plan Coronado National Forest Cochise, Graham, Pima, Pinal, and Santa Cruz Counties, Arizona Hidalgo County, New Mexico Responsible Official: Regional Forester Southwestern Region 333 Broadway Boulevard SE Albuquerque, NM 87102 (505) 842-3292 For more information contact: Forest Planner Coronado National Forest 300 West Congress, FB 42 Tucson, AZ 85701 (520) 388-8300 TTY 711 [email protected] ii Draft Land and Management Resource Plan Coronado National Forest Table of Contents Chapter 1: Introduction ...................................................................................... 1 Purpose of Land and Resource Management Plan ......................................... 1 Overview of the Coronado National Forest ..................................................... -

Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Chiricahua National Monument

In Cooperation with the University of Arizona, School of Natural Resources Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Chiricahua National Monument Open-File Report 2008-1023 U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey National Park Service This page left intentionally blank. In cooperation with the University of Arizona, School of Natural Resources Vascular Plant and Vertebrate Inventory of Chiricahua National Monument By Brian F. Powell, Cecilia A. Schmidt, William L. Halvorson, and Pamela Anning Open-File Report 2008-1023 U.S. Geological Survey Southwest Biological Science Center Sonoran Desert Research Station University of Arizona U.S. Department of the Interior School of Natural Resources U.S. Geological Survey 125 Biological Sciences East National Park Service Tucson, Arizona 85721 U.S. Department of the Interior DIRK KEMPTHORNE, Secretary U.S. Geological Survey Mark Myers, Director U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, Virginia: 2008 For product and ordering information: World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov/pubprod Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS For more information on the USGS-the Federal source for science about the Earth, its natural and living resources, natural hazards, and the environment: World Wide Web:http://www.usgs.gov Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS Suggested Citation Powell, B.F., Schmidt, C.A., Halvorson, W.L., and Anning, Pamela, 2008, Vascular plant and vertebrate inventory of Chiricahua National Monument: U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 2008-1023, 104 p. [http://pubs.usgs.gov/of/2008/1023/]. Cover photo: Chiricahua National Monument. Photograph by National Park Service. Note: This report supersedes Schmidt et al. (2005). Any use of trade, product, or firm names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. -

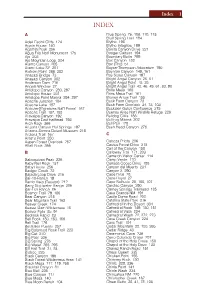

Index 1 INDEX

Index 1 INDEX A Blue Spring 76, 106, 110, 115 Bluff Spring Trail 184 Adeii Eechii Cliffs 124 Blythe 198 Agate House 140 Blythe Intaglios 199 Agathla Peak 256 Bonita Canyon Drive 221 Agua Fria Nat'l Monument 175 Booger Canyon 194 Ajo 203 Boundary Butte 299 Ajo Mountain Loop 204 Box Canyon 132 Alamo Canyon 205 Box (The) 51 Alamo Lake SP 201 Boyce-Thompson Arboretum 190 Alstrom Point 266, 302 Boynton Canyon 149, 161 Anasazi Bridge 73 Boy Scout Canyon 197 Anasazi Canyon 302 Bright Angel Canyon 25, 51 Anderson Dam 216 Bright Angel Point 15, 25 Angels Window 27 Bright Angel Trail 42, 46, 49, 61, 80, 90 Antelope Canyon 280, 297 Brins Mesa 160 Antelope House 231 Brins Mesa Trail 161 Antelope Point Marina 294, 297 Broken Arrow Trail 155 Apache Junction 184 Buck Farm Canyon 73 Apache Lake 187 Buck Farm Overlook 34, 73, 103 Apache-Sitgreaves Nat'l Forest 167 Buckskin Gulch Confluence 275 Apache Trail 187, 188 Buenos Aires Nat'l Wildlife Refuge 226 Aravaipa Canyon 192 Bulldog Cliffs 186 Aravaipa East trailhead 193 Bullfrog Marina 302 Arch Rock 366 Bull Pen 170 Arizona Canyon Hot Springs 197 Bush Head Canyon 278 Arizona-Sonora Desert Museum 216 Arizona Trail 167 C Artist's Point 250 Aspen Forest Overlook 257 Cabeza Prieta 206 Atlatl Rock 366 Cactus Forest Drive 218 Call of the Canyon 158 B Calloway Trail 171, 203 Cameron Visitor Center 114 Baboquivari Peak 226 Camp Verde 170 Baby Bell Rock 157 Canada Goose Drive 198 Baby Rocks 256 Canyon del Muerto 231 Badger Creek 72 Canyon X 290 Bajada Loop Drive 216 Cape Final 28 Bar-10-Ranch 19 Cape Royal 27 Barrio -

Arizona Regional Haze 308

Arizona State Implementation Plan Regional Haze Under Section 308 Of the Federal Regional Haze Rule Air Quality Division January 2011 (page intentionally blank) TABLE OF CONTENTS CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION........................................................................................................ 1 1.1 Overview of Visibility and Regional Haze..................................................................................2 1.2 Arizona Class I Areas.................................................................................................................. 3 1.3 Background of the Regional Haze Rule ......................................................................................3 1.3.1 The 1977 Clean Air Act Amendments................................................................................ 3 1.3.2 Phase I Visibility Rules – The Arizona Visibility Protection Plan ..................................... 4 1.3.3 The 1990 Clean Air Act Amendments................................................................................ 4 1.3.4 Submittal of Arizona 309 SIP............................................................................................. 6 1.4 Purpose of This Document .......................................................................................................... 9 1.4.1 Basic Plan Elements.......................................................................................................... 10 CHAPTER 2: ARIZONA REGIONAL HAZE SIP DEVELOPMENT PROCESS ......................... 15 2.1 Federal -

Camping in the Tucson Area Note: the Public Camping Areas Listed Below Charge Entrance Fees And/Or Camping Fees

Camping in the Tucson Area Note: The public camping areas listed below charge entrance fees and/or camping fees. Call the area you are interest- ed in for campsite availability, up to date fee information, fire closures, or any other information you need to plan your trip. For private campground information, contact either the Tucson Chamber of Commerce or the Tucson Visitors Bureau. Arizona State Parks Catalina State Park 123 drive-in campsites. Facilities include: (520) 628-5798 restrooms, showers, electricity, dump sta- Located 15 miles north of Tucson on State tion and water. * Due to budget Highway 77. constraints, some Picacho Peak State Park State Parks may be 100 drive-in campsites. Facilities include: (520) 466-3183 closed. Please check restrooms, showers, electricity and a dump website Located 40 miles north of Tucson on I-10 (exit 219). station. www.azstateparks. com Kartchner Caverns State Park (520) 586-4100 (tours/camping); 62 drive-in campsites. Facilities include: re- 586-2283 (tours/reservations) strooms, showers, electricity, dump station Located 9 miles south of I-10 (exit 302) on and water. State Highway 90. Pima County Parks Colossal Cave Mountain Park 30 drive-in campsites. Facilities include: (520) 647-7050 (camping & tours after chemical toilet and water. The main park hours); 647-7275 (tours only) gate is locked nightly, no entrance or exit Located 11 miles south of Saguaro Nation- after hours. 35’ limit on RV’s. al Park (east) on Old Spanish Trail. 150 drive-in campsites. Facilities include: Tucson Mountain Park (Gilbert Ray Campground) restrooms, electricity, dump station and (520) 883-4200 or 877-6000 water. -

Dos Cabezas Mountains Proposed LWC Is Affected Primarily by the Forces of Nature and Appears Natural to the Average Visitor

DOS CABEZAS MOUNTAINS LANDS WITH WILDERNESS CHARACTERISTICS PUBLIC LANDS CONTIGUOUS TO THE BLM’S DOS CABEZAS MOUNTAINS WILDERNESS IN THE NORTHERN CHIRICAHUA MOUNTAINS, ARIZONA A proposal report to the Bureau of Land Management, Safford Field Office, Arizona APRIL, 2016 Prepared by: Joseph M. Trudeau, Amber R. Fields, & Shannon Maitland Dos Cabezas Mountains Wilderness Contiguous Proposed LWC TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE: This Proposal was developed according to BLM Manual 6310 page 3 METHODS: The research approach to developing this citizens’ proposal page 5 Section 1: Overview of the Proposed Lands with Wilderness Characteristics Unit Introduction: Overview map showing unit location and boundaries page 8 • provides a brief description and labels for the units’ boundary Previous Wilderness Inventories: Map of former WSA’s or inventory unit’s page 9 • provides comparison between this and past wilderness inventories, and highlights new information Section 2: Documentation of Wilderness Characteristics The proposed LWC meets the minimum size criteria for roadless lands page 11 The proposed LWC is affected primarily by the forces of nature page 12 The proposed LWC provides outstanding opportunities for solitude and/or primitive and unconfined recreation page 16 A Sky Island Adventure: an essay and photographs by Steve Till page 20 MAP: Hiking Routes in the Dos Cabezas Mountains discussed in this report page 22 The proposed LWC has supplemental values that enhance the wilderness experience & deserve protection page 23 Conclusion: The proposed -

Galiuro Mountains Unit, Graham County, Arizona MLA 21

I MI~A~J~L M)P~SAL OF CORONADO I NATIONAL FOREST, PART 9 I Galiuro Mountains Unit I Graham County, Arizona I Galiuro Muni~Untains I i A IZON I,' ' I BUREAU OF MINES UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR f United States Department of the Interior BUREAU OF MINES INTERMOUNTAIN FIELD OPERATIONS CENTER "m II P.O. BOX 25086 II BUILDING 20, DENVER FEDERAL CENTER DENVER, COLORADO 80225 November 22, 1993 Nyal Niemuth Arizona Department of Mines and Mineral Resources 1502 West Washington Phoenix, AZ 85007 Dear Mr. Niemuth: Enclosed are two copies of the following U.S. Bureau of Mines Open File Report for your use: MLA 21-93 Mineral Appraisal of the Coronado National Forest, Part 9, Galiuro Mountains Unit, Graham County, Arizona If you would like additional copies, please notify Mark Chatman at 303-236-3400. Resource Evaluation Branch I i I MINERAL APPRAISAL OF THE CORONADO NATIONAL FOREST PART 9, GALIURO MOUNTAINS UNIT, I GRAHAM COUNTY, ARIZONA I I by. I S. Don Brown I MLA 21-93 I 1993 I I, i Intermountain Field Operations Center I Denver, Colorado I UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR I BRUCE BABBITT, Secretary BUREAU OF MINES I HERMANN ENZER, Acting Director I I I PREFACE I A January 1987 Interagency Agreement between the U.S. Bureau of Mines, U.S. Geological Survey, and U.S. Forest Service describes the purpose, authority, and I program operation for the forest-wide studies. The program is intended to assist the I Forest Service in incorporating mineral resource data in forest plans as specified by the National Forest Management Act (1976) and Title 36, Chapter 2, Part 219, Code of i Federal Regulations, and to augment the Bureau's mineral resource data base so that it can analyze and make available minerals information as required by the National I Materials and Minerals Policy, Research and Development Act (1980). -

Species at Risk on Department of Defense Installations

Species at Risk on Department of Defense Installations Revised Report and Documentation Prepared for: Department of Defense U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Submitted by: January 2004 Species at Risk on Department of Defense Installations: Revised Report and Documentation CONTENTS 1.0 Executive Summary..........................................................................................iii 2.0 Introduction – Project Description................................................................. 1 3.0 Methods ................................................................................................................ 3 3.1 NatureServe Data................................................................................................ 3 3.2 DOD Installations............................................................................................... 5 3.3 Species at Risk .................................................................................................... 6 4.0 Results................................................................................................................... 8 4.1 Nationwide Assessment of Species at Risk on DOD Installations..................... 8 4.2 Assessment of Species at Risk by Military Service.......................................... 13 4.3 Assessment of Species at Risk on Installations ................................................ 15 5.0 Conclusion and Management Recommendations.................................... 22 6.0 Future Directions.............................................................................................