Chomolhari - One Perfect Day

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis of Vegetation Condition and Its Relationship with Meteorological Variables in the Yarlung Zangbo River Basin of China

Innovative water resources management – understanding and balancing interactions between humankind and nature Proc. IAHS, 379, 105–112, 2018 https://doi.org/10.5194/piahs-379-105-2018 Open Access © Author(s) 2018. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Analysis of vegetation condition and its relationship with meteorological variables in the Yarlung Zangbo River Basin of China Xianming Han1,2, Depeng Zuo1,2, Zongxue Xu1,2, Siyang Cai1,2, and Xiaoxi Gao1,2 1College of Water Sciences, Beijing Normal University, Beijing 100875, China 2Beijing Key Laboratory of Urban Hydrological Cycle and Sponge City Technology, Beijing 100875, China Correspondence: Depeng Zuo ([email protected]) Received: 31 December 2017 – Accepted: 12 January 2018 – Published: 5 June 2018 Abstract. The Yarlung Zangbo River Basin is located in the southwest border of China, which is of great significance to the socioeconomic development and ecological environment of Southwest China. Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI) is an important index for investigating the change of vegetation cover, which is widely used as the representation value of vegetation cover. In this study, the NDVI is adopted to explore the vegetation condition in the Yarlung Zangbo River Basin during the recent 17 years, and the relationship between NDVI and meteorological variables has also been discussed. The results show that the annual maximum value of NDVI usually appears from July to September, in which August occupies a large proportion. The minimum value of NDVI appears from January to March, in which February takes up most of the percentage. The higher values of NDVI are generally located in the lower elevation area. -

6 Days Lhasa Gyantse Shigatse Group Tour

[email protected] +86-28-85593923 6 days Lhasa Gyantse Shigatse group tour https://windhorsetour.com/tibet-group-tour/8-day-central-tibet-cultural-tour Lhasa Gyantse Shigatse Lhasa Enjoy an awe-inspiring tour to explore the Tibetan culture and history with a visits to Lhasa's Potala Palace and Tashilunpo Monastery in Shigatse. Along the way you will be immersed into the breathtaking scenery of Yamdrok Lake and beyond. Type Group, maximum of 12 person(s) Duration 6 days Theme Culture and Heritage Trip code FDT-03 Tour dates From ¥ 4,550 Itinerary Join in a budget Tibet group tour to explore the mysterious snow land, enjoying the spectacular landscape around Yamdrok Lake, listen to pilgrim chanting as you cross Lhasa city. New friends, exploring the unique Tibetan history and more awaits. Day 01 : Arrival in Lhasa [3,658 m] Your Tibetan guide will greet you at the Lhasa Gonggar Airport or Lhasa railway station upon your arrival, and then transfer you to your hotel in the city. From the airport to Lhasa is 68 km (42 mi), roughly an hour drive to your hotel. The drive from the train station is only 15 km (9 mi) and takes 20 minutes. During the course of the ride, you will not only be amazed by the spectacular scenery of the Tibetan plateau, the scattered Tibetan villages, but certainly by the hospitality of your guide and driver, as well! After checking into the hotel, you will have the remainder of the day to rest and acclimatize to the high altitude. Day 02 : Lhasa City Sightseeing (B) In the morning, you will visit Potala Palace. -

Report on Domestic Animal Genetic Resources in China

Country Report for the Preparation of the First Report on the State of the World’s Animal Genetic Resources Report on Domestic Animal Genetic Resources in China June 2003 Beijing CONTENTS Executive Summary Biological diversity is the basis for the existence and development of human society and has aroused the increasing great attention of international society. In June 1992, more than 150 countries including China had jointly signed the "Pact of Biological Diversity". Domestic animal genetic resources are an important component of biological diversity, precious resources formed through long-term evolution, and also the closest and most direct part of relation with human beings. Therefore, in order to realize a sustainable, stable and high-efficient animal production, it is of great significance to meet even higher demand for animal and poultry product varieties and quality by human society, strengthen conservation, and effective, rational and sustainable utilization of animal and poultry genetic resources. The "Report on Domestic Animal Genetic Resources in China" (hereinafter referred to as the "Report") was compiled in accordance with the requirements of the "World Status of Animal Genetic Resource " compiled by the FAO. The Ministry of Agriculture" (MOA) has attached great importance to the compilation of the Report, organized nearly 20 experts from administrative, technical extension, research institutes and universities to participate in the compilation team. In 1999, the first meeting of the compilation staff members had been held in the National Animal Husbandry and Veterinary Service, discussed on the compilation outline and division of labor in the Report compilation, and smoothly fulfilled the tasks to each of the compilers. -

TIBET - NEPAL Septembre - Octobre 2021

VOYAGE PEKIN - TIBET - NEPAL Septembre - octobre 2021 VOYAGE PEKIN - TIBET - NEPAL Itinéraire de 21 jours Genève - Zurich - Beijing - train - Lhasa - Gyantse - Shigatse - Shelkar - Camp de base de l’Everest - Gyirong - Kathmandu - Parc National de Chitwan - Kathmandu - Delhi - Zurich - Genève ITINERAIRE EN UN CLIN D’ŒIL 1 15.09.2021 Vol Suisse - Beijing 2 16.09.2021 Arrivée à Beijing 3 17.09.2021 Beijing 4 18.09.2021 Beijing 5 19.09.2021 Beijing - Train de Pékin vers le Tibet 6 20.09.2021 Train 7 21.09.2021 Arrivée à Lhassa 8 22.09.2021 Lhassa 9 23.09.2021 Lhassa 10 24.09.2021 Lhassa - Lac Yamdrok - Gyantse 11 25.09.2021 Gyantse - Shigatse 12 26.09.2021 Shigatse - Shelkar 13 27.09.2021 Shelkar - Rongbuk - Camp de base de l'Everest 14 28.09.2021 Rongbuk - Gyirong 15 29.09.2021 Gyirong – Rasuwa - Kathmandou 16 30.09.2021 Kathmandou 17 01.10.2021 Kathmandou - Parc national de Chitwan 18 02.10.2021 Parc national de Chitwan 19 03.10.2021 Parc national de Chitwan - Kathmandou 20 04.10.2021 Vol Kathmandou - Delhi - Suisse 21 05.10.2021 Arrivée en Suisse Itinéraire Tibet googlemap de Lhassa à Gyirong : https://goo.gl/maps/RN7H1SVXeqnHpXDP6 Itinéraire Népal googlemap de Rasuwa au Parc National de Chitwan : https://goo.gl/maps/eZLHs3ACJQQsAW7J7 ITINERAIRE DETAILLE : Jour 1 / 2 : VOL GENEVE – ZURICH (OU SIMILAIRE) - BEIJING Enregistrement de vos bagages au moins 2h00 avant l’envol à l’un des guichets de la compagnie aérienne. Rue du Midi 11 – 1003 Lausanne +41 21 311 26 87 ou + 41 78 734 14 03 @ [email protected] Jour 2 : ARRIVEE A BEIJING A votre arrivée à Beijing, formalités d’immigration, accueil par votre guide et transfert à l’hôtel. -

News China March. 13.Cdr

VOL. XXV No. 3 March 2013 Rs. 10.00 The first session of the 12th National People’s Congress (NPC) opens at the Great Hall of the People in Beijing, capital of China on March 5, 2013. (Xinhua/Pang Xinglei) Chinese Ambassador to India Mr. Wei Wei meets Indian Chinese Vice Foreign Minister Cheng Guoping , on behalf Foreign Minister Salman Khurshid in New Delhi on of State Councilor Dai Bingguo, attends the dialogue on February 25, 2013. During the meeting the two sides Afghanistan issue held in Moscow,together with Russian exchange views on high-level interactions between the two Security Council Secretary Nikolai Patrushev and Indian countries, economic and trade cooperation and issues of National Security Advisor Shivshankar Menon on February common concern. 20, 2013. Chinese Ambassador to India Mr.Wei Wei and other VIP Chinese Ambassador to India Mr. Wei Wei and Indian guests are having a group picture with actors at the 2013 Minister of Culture Smt. Chandresh Kumari Katoch enjoy Happy Spring Festival organized by the Chinese Embassy “China in the Spring Festival” exhibition at the 2013 Happy and FICCI in New Delhi on February 25,2013. Artists from Spring Festival. The exhibition introduces cultures, Jilin Province, China and Punjab Pradesh, India are warmly customs and traditions of Chinese Spring Festival. welcomed by the audience. Chinese Ambassador to India Mr. Wei Wei(third from left) Chinese Ambassador to India Mr. Wei Wei visits the participates in the “Happy New Year “ party organized by Chinese Visa Application Service Centre based in the Chinese Language Department of Jawaharlal Nehru Southern Delhi on March 6, 2013. -

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level

Table of Codes for Each Court of Each Level Corresponding Type Chinese Court Region Court Name Administrative Name Code Code Area Supreme People’s Court 最高人民法院 最高法 Higher People's Court of 北京市高级人民 Beijing 京 110000 1 Beijing Municipality 法院 Municipality No. 1 Intermediate People's 北京市第一中级 京 01 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Shijingshan Shijingshan District People’s 北京市石景山区 京 0107 110107 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Haidian District of Haidian District People’s 北京市海淀区人 京 0108 110108 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Mentougou Mentougou District People’s 北京市门头沟区 京 0109 110109 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Municipality Changping Changping District People’s 北京市昌平区人 京 0114 110114 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Yanqing County People’s 延庆县人民法院 京 0229 110229 Yanqing County 1 Court No. 2 Intermediate People's 北京市第二中级 京 02 2 Court of Beijing Municipality 人民法院 Dongcheng Dongcheng District People’s 北京市东城区人 京 0101 110101 District of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Xicheng District Xicheng District People’s 北京市西城区人 京 0102 110102 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Fengtai District of Fengtai District People’s 北京市丰台区人 京 0106 110106 Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality 1 Fangshan District Fangshan District People’s 北京市房山区人 京 0111 110111 of Beijing 1 Court of Beijing Municipality 民法院 Municipality Daxing District of Daxing District People’s 北京市大兴区人 京 0115 -

China/Tibet: Unterschiedliche Na- Men Geographischer Orte Und Kenntnisse Der Administrativen Einheiten

China/Tibet: Unterschiedliche Na- men geographischer Orte und Kenntnisse der administrativen Einheiten Auskunft Adrian Schuster Bern, 2. Dezember 2015 1 Einleitung Die Schweizerische Flüchtlingshilfe hat verschiedene Fragen zur aktuellen Situation, zum Alltag und der Lebenswelt der lokalen Bevölkerung in Tibet erhalten. Diese Auskunft behandelt Fragen zu den unterschiedlichen Namen geographischer Orte, den administrativen Einheiten Tibets sowie den Kenntnissen der lokalen Bevölke- rung dazu. Diese Auskunft basiert auf Expertenauskünften 1 und auf eigenen Recher- chen. 2 Schwierigkeiten bezüglich allgemeingültiger Aussagen Generalisierungen nicht möglich. Nach Angaben verschiedener Expertinnen und Experten zu Tibet können Angaben zu diversen Fragen des Alltags der ti betischen Bevölkerung meist nicht in generalisierender Form gemacht werden. Nach der am 31. März 2015 gemachten Einschätzung von Geoff Barstow 2 von der Otterbein Uni- versität in Westerville USA, kann sich die Situation in den verschiedenen Gebieten sehr stark unterscheiden.3 Die Beantwortung von Fragen zum Alltag sowie der ver- schiedenen Aspekte des Lebens der Tibeterinnen und Tibeter innerhalb des Auto- nomen Gebiets Tibet (AGT) sowie in den Gebieten ausserhalb des AGT ist deshalb äusserst komplex. Diese Angaben machte eine Kontaktperson 4 mit Expertenwissen zu Ost-Tibet am 28. April 2015 aufgrund der vielfältigen regionalen Unterschiede sowie den Unterschieden zwischen den ländlichen und urbanen Gebieten. Eine Ge- neralisierung und Übertragung einzelner Erkenntnisse, die für eine spezifische Re- gion gelten, auf andere Regionen und Provinzen im Autonomen Gebiet Tibet sowie auf die ausserhalb liegenden tibetischen Gebiete, ist laut der Kontaktperson nicht möglich.5 Anne Carolyn Klein, Professorin vom Department of Religion der Rice Uni- versity in Virginia betont in einer Publikation aus dem Jahr 2008 ebenfalls, dass die grosse Vielfalt in Tibet es unmöglich macht, Generalisierungen zu ganz Tibet zu 1 Entsprechend den COI-Standards verwendet die SFH öffentlich zugängliche Quellen. -

2008 UPRISING in TIBET: CHRONOLOGY and ANALYSIS © 2008, Department of Information and International Relations, CTA First Edition, 1000 Copies ISBN: 978-93-80091-15-0

2008 UPRISING IN TIBET CHRONOLOGY AND ANALYSIS CONTENTS (Full contents here) Foreword List of Abbreviations 2008 Tibet Uprising: A Chronology 2008 Tibet Uprising: An Analysis Introduction Facts and Figures State Response to the Protests Reaction of the International Community Reaction of the Chinese People Causes Behind 2008 Tibet Uprising: Flawed Tibet Policies? Political and Cultural Protests in Tibet: 1950-1996 Conclusion Appendices Maps Glossary of Counties in Tibet 2008 UPRISING IN TIBET CHRONOLOGY AND ANALYSIS UN, EU & Human Rights Desk Department of Information and International Relations Central Tibetan Administration Dharamsala - 176215, HP, INDIA 2010 2008 UPRISING IN TIBET: CHRONOLOGY AND ANALYSIS © 2008, Department of Information and International Relations, CTA First Edition, 1000 copies ISBN: 978-93-80091-15-0 Acknowledgements: Norzin Dolma Editorial Consultants Jane Perkins (Chronology section) JoAnn Dionne (Analysis section) Other Contributions (Chronology section) Gabrielle Lafitte, Rebecca Nowark, Kunsang Dorje, Tsomo, Dhela, Pela, Freeman, Josh, Jean Cover photo courtesy Agence France-Presse (AFP) Published by: UN, EU & Human Rights Desk Department of Information and International Relations (DIIR) Central Tibetan Administration (CTA) Gangchen Kyishong Dharamsala - 176215, HP, INDIA Phone: +91-1892-222457,222510 Fax: +91-1892-224957 Email: [email protected] Website: www.tibet.net; www.tibet.com Printed at: Narthang Press DIIR, CTA Gangchen Kyishong Dharamsala - 176215, HP, INDIA ... for those who lost their lives, for -

Tibet Is My Country

TIBET IS MY COUNTRY The Autobiography of TIHUBTEN JIGME NORBU Brother of the Dalai Lama as told to HEINRICH HARRER Translated from the German by EDWARD FITZGERALD E. P. DUTTON & CO., INC. NEW YORK 1981 First published in the U.S.A., 1961, by E. P. Dutton 81 Co., Inc. English Translation copyright, 0, 1960 by E. P. Dutton and Co., Inc., New York, and Rupert Hart-Davis Ltd., London. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. FIRST EDITION (i No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a review written for inclusion in a magazine, newspaper or broadcast. First piiblished in Germany under the title of TIBET VERLORENE HEIMAT original edition 0, 1960 by Verlag Ullstein GmbH Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 61-5040 TO HIS HOLINESS THE DALAI LAMA IN RESPECT AND FRATERNAL LOVE The Tibetan Calendar 1927 Fire-Hare Year 1957 Fire-Bird Year 1928 Earth-Dragon Year 1958 Earth-Dog Year 1929 Earth-Snake Year 1959 Earth-Pig Year 1930 Iron-Horse Year 1960 Iron-Mouse Year 1931 Iron-Sheep Year 1961 Iron-Bull Year 1932 Water-Ape Year 1962 Water-Tiger Year 1933 Water-Bird Year 1963 Water-Hare Year 1934 Wood-Dog Year 1964 Wood-Dragon Year 1935 Wood-Pig Year 1965 Wood-Snake Year 1936 Fire-Mouse Year 1966 Fire-Horse Year 1937 Fire-Bull Year 1967 Fire-Sheep Year 1938 Earth-Tiger Year I 968 Earth-Ape Year 1939 Earth-Hare Year 1969 Earth-Bird Year I 940 Iron-Dragon Year I 970 Iron-Dog Year 1941 Iron-Snake Year I 97I Iron-Pig -

February 2016

INTERNATIONAL U.S.-Russia Relations 2016 Reg. ss-973 February www.southasia.com.pk INSIDE INDIA SRI LANKA AFGHANISTAN NEIGHBOR Local Focus Sad Saga No Child’s Play The Deal and After ISIS Marches Recent incidentsEast of violence in Afghanistan, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Indonesia indicate that the Islamic State (IS) is moving eastwards from Syria and Iraq. Afghanistan Afg. 50 India Rs. 65 Philippines P 75 Australia A$ 6 Japan ¥ 500 Saudi Arabia SR 15 Bangladesh Taka 65 Korea Won 3000 Singapore S$ 8 Bhutan NU 45 Malaysia RM 6 Sri Lanka Rs. 100 Brazil BRL 20 Maldives Rf 45 Thailand B 100 Canada C$ 6 Myanmar MMK10 Turkey Lira. 2 China RMB 30 Nepal NcRs. 75 UAE AED 10 France Fr 30 New Zealand NZ$ 7 UK £ 3 Hong Kong HK$ 30 Pakistan Rs. 150 USA $ 5 Ad 2 Contents 12 Eastward Bound The IS looks for new territories to conquer. India Sri Lanka 26Local Focus ‘Make In India’ is still Sad Saga groping in the dark. The unwanted dividends of 32 prosperity. Nepal Big Brother Politics Nepal should get better 36 treatment from India. The Maldives Indian Ocean Turmoil 38 The pains of growth. 30 Bangladesh Rising Religious Extremism A surge of Islamic fundamentalism. 4 SOUTHASIA • FEBRUARY 2016 REGULAR FEATURES Editor’s Mail 8 On Record 9 Briefs 10 COVER STORY Eastward Bound 12 IS and Saarc 16 Changing Directions 20 Expanding Territory 22 REGION Pakistan Honour Among Thieves 24 India Local Focus 26 Afghanistan Shattered Country 28 42 Bangladesh International Rising Religious Extremism 30 Hot and Cold Sri Lanka Indications for world peace. -

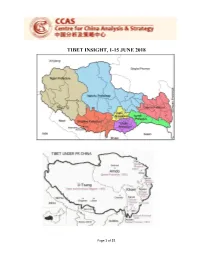

Tibet Insight, 1-15 June 2018

TIBET INSIGHT, 1-15 JUNE 2018 Page 1 of 21 TAR NEWS TAR Party Secretary visits Kindergarten June 01, 2018 On International Children’s Day on May 31, TAR Party Secretary Wu Yingjie visited a Bilingual kindergarten in Chengguan district of Lhasa. Posters highlighting the contrast between “old and new Tibet” were pasted in the corridors of the school. TAR Party Secretary Wu Yingjie advised the children to understand the trust and loyalty of the Party and to remember Chinese President Xi Jinping's message of safeguarding the motherland's unity. Training Course for Lhasa’s Budget Performance June 05, 2018 A training class for enhancing efficiency in Lhasa’s budget performance began in Lhasa on June 4. Well-known experts were invited, including a Professor from Beijing’s Information Science and Technology University who gave a lecture on financial performance and management. The Training was especially to strengthen the budgetary performance of the Central Party’s special funds. All departments have been mandated to achieve an overall budget performance target of over 300,000 Yuan by end of the fiscal year 2019. The Lhasa Municipal Government has also established a mechanism to assess nine key livelihood policies and major projects in Lhasa. Tibet University Takes Measures to Promote Teachers' Teaching Skills June 05, 2018 Since March 2018, the Tibet University has launched a large number of military training activities for teachers. To oversee the progress of this training, a group comprising “excellent teachers with high moral character, excellent professional skills, and strong educational and teaching abilities” was constituted. According to the arrangement, Tibet University has organized departments to further study the State Council's "Opinions on Comprehensively Deepening the Reform of the Teaching Staff in the New Era", "National Standards for Undergraduate Teaching Quality", "Undergraduate Professional Certification Standards" and "Tibetan College Teacher's Classroom Basic Requirements" etc. -

© 生物多样性biodiversity Science

胡一鸣, 梁健超, 金崑, 丁志锋, 周智鑫, 胡慧建, 蒋志刚. 喜马拉雅山哺乳动物物种多样性垂直分布格局. 生物多样性, 2018, 26 (2): 191–201. http://www.biodiversity-science.net/CN/10.17520/biods.2017324 附录 1 哺乳动物物种数据获取的主要方法 Appendix 1 Methods for acquiring data of mammal species 1.1 野外调查时间与样线布设情况 1.1 Survey area, date of survey and sampling effort 调查区域 调查日期 样线数量 样线总长度 Survey area Date of survey Number of transects Total length of the transects (km) 吉隆县吉隆沟 Gyirong Valley, 2012.05.10-2012.10.13, 46 110.0 Gyirong county 2013.07.09-2013.09.05, 2017.06.20-2017.06.26. 聂拉木县樟木沟 Zhangmu Valley, 2013.07.11-2013.07.20, 22 89.8 Nyalam County 2017.06.16-2017.06.23. 定日县绒线沟 Rongxian Valley, 2013.09.12-2013.09.16. 11 56.7 Tingri County 定日县嘎玛沟 Gama Valley, Tingri 2013.05.15-2013.05.23. 1 62.4 County 定结县陈塘沟 Chentang Valley, 2013.05.15-2013.05.23. 10 91.3 Dinggyê County 亚东县亚东沟 Yadong Valley, 2013.05.16-2013.05.24, 22 91.7 Yadong County 2017.06.10-2017.06.16. 洛扎县多布沟 Duobu Valley, 2013.09.29-2013.10.04. 10 51.3 Lhozhag County 错那县勒布沟 Lubu Valley, Cona 2013.09.28-2013.10.05, 30 58.6 County 2017.06.03-2017.06.09. 错那县浪坡沟 Langpo Valley, Cona 2013.09.26-2013.09.27, 5 29.3 County 2015.06.06-2015.06.07. 隆子县玉麦沟 Yumai Valley, 2013.09.23-2013.09.14, 3 15.0 Lhünzê County 2015.06.04-2015.06.05. 隆子县扎日沟 Zhari Valley, Lhünzê 2013.09.20-2013.09.24, 12 64.8 County 2015.05.30-2015.06.04.