Arms for Despots and the Powerlessness of Public Opinion

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commentary by Miriam Saage-Maaβ Vice Legal Director & Coordinator of Business & Human Rights Program European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights July 2012

How serious is the international community of states about human rights standards for business? commentary by Miriam Saage-Maaβ Vice Legal Director & coordinator of Business & Human Rights program European Center for Constitutional and Human Rights July 2012 Recent developments have shown one more time that the struggle for human rights is not only about the creation of international standards so that the rule of law may prevail. The struggle for human rights is also a struggle between different economic and political interests, and it is a question of power which interests prevail. 2011 was an important year for the development of standards in the field of business and human rights. In May 2011 the OECD member states approved a revised version of the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises, introducing a new human rights chapter. Only a month later the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) endorsed by consensus the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights.1 These two international documents are both designed to provide a global standard for preventing and addressing the risk of business-related human rights violations. In particular, the UN Guiding Principles focus on the “State Duty to Protect” and the “Corporate Responsibility to Respect” in addition to the “Access to Remedy” principle. This principle seeks to ensure that when people are harmed by business activity, there is both adequate accountability and effective redress, both judicial and non-judicial. The Guiding Principles clearly call on states to ensure -

Papers Situation Gruenen

PAPERS JOCHEN WEICHOLD ZUR SITUATION DER GRÜNEN IM HERBST 2014 ROSA LUXEMBURG STIFTUNG JOCHEN WEICHOLD ZUR SITUATION DER GRÜNEN IM HERBST 2014 REIHE PAPERS ROSA LUXEMBURG STIFTUNG Zum Autor: Dr. JOCHEN WEICHOLD ist freier Politikwissenschaftler. IMPRESSUM PAPERS wird herausgegeben von der Rosa-Luxemburg-Stiftung und erscheint unregelmäßig V. i. S . d. P.: Martin Beck Franz-Mehring-Platz 1 • 10243 Berlin • www.rosalux.de ISSN 2194-0916 • Redaktionsschluss: November 2014 Gedruckt auf Circleoffset Premium White, 100 % Recycling 2 Inhalt Einleitung 5 Wahlergebnisse der Grünen bei Europa- und bei Bundestagswahlen 7 Ursachen für die Niederlage der Grünen bei der Bundestagswahl 2013 11 Wählerwanderungen von und zu den Grünen bei Europa- und bei Bundestagswahlen 16 Wahlergebnisse der Grünen bei Landtags- und bei Kommunalwahlen 18 Zur Sozialstruktur der Wähler der Grünen 24 Mitgliederentwicklung der Grünen 32 Zur Sozialstruktur der Mitglieder der Grünen 34 Politische Positionen der Partei Bündnis 90/Die Grünen 36 Haltung der Grünen zu aktuellen Fragen 46 Innerparteiliche Differenzierungsprozesse bei den Grünen 48 Ausblick: Schwarz-Grün auf Bundesebene? 54 Anhang 58 Zusammensetzung des Bundesvorstandes der Grünen (seit Oktober 2013) 58 Zusammensetzung des Parteirates der Grünen (seit Oktober 2013) 58 Abgeordnete der Grünen im Deutschen Bundestag im Ergebnis der Bundestagswahl 2013 59 Abgeordnete der Grünen im Europäischen Parlament im Ergebnis der Europawahl 2014 61 Wählerwanderungen von bzw. zu den Grünen bei der Landtagswahl in Sachsen 2014 im Vergleich zur Landtagswahl 2009 62 3 Wählerwanderungen von bzw. zu den Grünen bei der Landtagswahl in Brandenburg 2014 im Vergleich zur Landtagswahl 2009 62 Wählerwanderungen von bzw. zu den Grünen bei der Landtagswahl in Thüringen 2014 im Vergleich zur Landtagswahl 2009 63 Zur Sozialstruktur der Grün-Wähler bei den Landtagswahlen in Branden- burg, Sachsen und Thüringen 2014 63 Anmerkungen 65 4 Einleitung Die Partei Bündnis 90/Die Grünen (Grüne) stellt zwar mit 63 Abgeordneten die kleinste Fraktion im Deutschen Bundestag. -

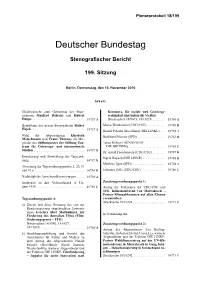

Plenarprotokoll 16/220

Plenarprotokoll 16/220 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 220. Sitzung Berlin, Donnerstag, den 7. Mai 2009 Inhalt: Glückwünsche zum Geburtstag der Abgeord- ter und der Fraktion DIE LINKE: neten Walter Kolbow, Dr. Hermann Scheer, Bundesverantwortung für den Steu- Dr. h. c. Gernot Erler, Dr. h. c. Hans ervollzug wahrnehmen Michelbach und Rüdiger Veit . 23969 A – zu dem Antrag der Abgeordneten Dr. Erweiterung und Abwicklung der Tagesord- Barbara Höll, Dr. Axel Troost, nung . 23969 B Dr. Gregor Gysi, Oskar Lafontaine und der Fraktion DIE LINKE: Steuermiss- Absetzung des Tagesordnungspunktes 38 f . 23971 A brauch wirksam bekämpfen – Vor- handene Steuerquellen erschließen Tagesordnungspunkt 15: – zu dem Antrag der Abgeordneten Dr. a) Erste Beratung des von den Fraktionen der Barbara Höll, Wolfgang Nešković, CDU/CSU und der SPD eingebrachten Ulla Lötzer, weiterer Abgeordneter Entwurfs eines Gesetzes zur Bekämp- und der Fraktion DIE LINKE: Steuer- fung der Steuerhinterziehung (Steuer- hinterziehung bekämpfen – Steuer- hinterziehungsbekämpfungsgesetz) oasen austrocknen (Drucksache 16/12852) . 23971 A – zu dem Antrag der Abgeordneten b) Beschlussempfehlung und Bericht des Fi- Christine Scheel, Kerstin Andreae, nanzausschusses Birgitt Bender, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion BÜNDNIS 90/DIE – zu dem Antrag der Fraktionen der GRÜNEN: Keine Hintertür für Steu- CDU/CSU und der SPD: Steuerhin- erhinterzieher terziehung bekämpfen (Drucksachen 16/11389, 16/11734, 16/9836, – zu dem Antrag der Abgeordneten Dr. 16/9479, 16/9166, 16/9168, 16/9421, Volker Wissing, Dr. Hermann Otto 16/12826) . 23971 B Solms, Carl-Ludwig Thiele, weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion der Lothar Binding (Heidelberg) (SPD) . 23971 D FDP: Steuervollzug effektiver ma- Dr. Hermann Otto Solms (FDP) . 23973 A chen Eduard Oswald (CDU/CSU) . -

Kettenduldungen Abschaffen

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 16/687 16. Wahlperiode 16. 02. 2006 Antrag der Abgeordneten Josef Philip Winkler, Volker Beck (Köln), Britta Haßelmann, Monika Lazar, Jerzy Montag, Claudia Roth (Augsburg), Irmingard Schewe-Gerigk, Hans-Christian Ströbele, Silke Stokar von Neuforn, Wolfgang Wieland und der Fraktion BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN Kettenduldungen abschaffen Der Bundestag wolle beschließen: I. Der Deutsche Bundestag stellt fest: Die Anwendung des § 25 des Aufenthaltsgesetzes (AufenthG) durch die Länder steht nicht in Einklang mit dem Ziel des Gesetzgebers, die Kettenduldungen ab- zuschaffen. II. Der Bundestag fordert die Bundesregierung daher auf, folgende Maßnahmen zu treffen: 1. Die Bundesregierung sorgt gegenüber den Bundesländern bis Ende März 2006 für eine Klarstellung in den vorläufigen Anwendungshinweisen des Bundesministeriums des Innern, die dem Ziel des Gesetzgebers entspricht. Hierin sind insbesondere die Zumutbarkeit einer Ausreise sowie die beson- dere Situation in Deutschland aufgewachsener Kinder und Jugendlicher zu berücksichtigen. 2. Die Bundesregierung legt dem Deutschen Bundestag zeitnah einen Gesetz- entwurf zur Änderung von § 25 Abs. 5 AufenthG vor, der der Intention des Gesetzgebers gerecht wird, wenn auf dem vorgenannten Weg keine Ände- rung der Praxis der Bundesländer zu erreichen ist. Berlin, den 15. Februar 2006 Renate Künast, Fritz Kuhn und Fraktion Begründung Der ehemalige Bundesminister des Innern, Otto Schily, hatte in der Debatte zur Verabschiedung des Zuwanderungsgesetzes vor dem Deutschen Bundestag er- -

Plenarprotokoll 18/199

Plenarprotokoll 18/199 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 199. Sitzung Berlin, Donnerstag, den 10. November 2016 Inhalt: Glückwünsche zum Geburtstag der Abge- Kommerz, für soziale und Genderge- ordneten Manfred Behrens und Hubert rechtigkeit und kulturelle Vielfalt Hüppe .............................. 19757 A Drucksachen 18/8073, 18/10218 ....... 19760 A Begrüßung des neuen Abgeordneten Rainer Marco Wanderwitz (CDU/CSU) .......... 19760 B Hajek .............................. 19757 A Harald Petzold (Havelland) (DIE LINKE) .. 19762 A Wahl der Abgeordneten Elisabeth Burkhard Blienert (SPD) ................ 19763 B Motschmann und Franz Thönnes als Mit- glieder des Stiftungsrates der Stiftung Zen- Tabea Rößner (BÜNDNIS 90/ trum für Osteuropa- und internationale DIE GRÜNEN) ..................... 19765 C Studien ............................. 19757 B Dr. Astrid Freudenstein (CDU/CSU) ...... 19767 B Erweiterung und Abwicklung der Tagesord- Sigrid Hupach (DIE LINKE) ............ 19768 B nung. 19757 B Matthias Ilgen (SPD) .................. 19769 A Absetzung der Tagesordnungspunkte 5, 20, 31 und 41 a ............................. 19758 D Johannes Selle (CDU/CSU) ............. 19769 C Nachträgliche Ausschussüberweisungen ... 19759 A Gedenken an den Volksaufstand in Un- Zusatztagesordnungspunkt 1: garn 1956 ........................... 19759 C Antrag der Fraktionen der CDU/CSU und SPD: Klimakonferenz von Marrakesch – Pariser Klimaabkommen auf allen Ebenen Tagesordnungspunkt 4: vorantreiben Drucksache 18/10238 .................. 19771 C a) -

Framing the Same-Sex Marriage Debate in the 17Th Session of the German Bundestag

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2014 Ja, Ich Will: Framing the Same-Sex Marriage Debate in the 17th Session of the German Bundestag Stephen Colby Woods University of Mississippi. Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Woods, Stephen Colby, "Ja, Ich Will: Framing the Same-Sex Marriage Debate in the 17th Session of the German Bundestag" (2014). Honors Theses. 875. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/875 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JA, ICH WILL: FRAMING THE SAME-SEX MARRIAGE DEBATE IN THE 17TH SESSION OF THE GERMAN BUNDESTAG 2014 By S. Colby Woods A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion Of the Bachelor of Arts degree in International Studies Croft Institute for International Studies Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College University of Mississippi University of Mississippi May 2014 Approved: __________________________ Advisor: Dr. Ross Haenfler __________________________ Reader: Dr. Kees Gispen __________________________ Reader: Dr. Alice Cooper © 2014 Stephen Colby Woods ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS AND DEDICATION I would first like to thank the Croft Institute for International Studies and the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College for fostering my academic growth and development over the past four years. I want to express my sincerest gratitude to my thesis advisor, Dr. -

New Legislation in Germany Concerning Same-Sex Unions

NEW LEGISLATION IN GERMANY CONCERNING SAME-SEX UNIONS Stephen Ross Levitt* Freudvoll und leidvoll, gedankenvoll sein, langen und bangen in schwebender Pein; himmelhoch jauchzend, zum Tode betrUbt- glUcklich allein ist die Seele, die liebt.* Johann Wolfgang Von Goethe I. INTRODUCTION ....................................... 470 II. THE HISTORICAL BACKGROUND .......................... 471 I. POLITICAL BACKGROUND OF THE LAST TEN YEARS .......... 473 IV. THE "HAMBURG MARRIAGE" LEGISLATION AND THE RESOLUTION FROM THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT ............ 474 V. THE LEGISLATION PROPOSED BY THE FDP ................. 475 VI. THE DRAFT LEGISLATION FROM JULY 4TH, 2000 ............. 477 VII. THE BUNDESRAT AND THE SAME-SEX PARTNERSHIP LEGISLATION ........................................ 479 VIII. THE LEGISLATION GOVERNING SAME-SEX PARTNERSHIPS ..... 481 IX. CONSTITUTIONAL CHALLENGES .......................... 488 X. CONCLUSION ........................................ 493 * Assistant Professor of Legal Studies in the Liberal Arts Department, Farquhar Center for Undergraduate Studies, Nova Southeastern University; B.A., York University (Canada), 1985; LLB., Osgoode Hall Law School, (Toronto, Canada) 1985; LLM., University of London (LS.E.) 1986. Translations from German into English are the author's unless otherwise noted. The author would like to thank the following for their assistance with this article: Ms. Brenda Cox- Graham, Barrister and Solicitor, (Hamilton, Canada); Mr. Marco Dattini, Attorney (Fort Lauderdale, Florida); Dr. Lester Lindley (Libertyville, -

Abstimmungsergebnis 20170601 11-Data

Deutscher Bundestag 237. Sitzung des Deutschen Bundestages am Donnerstag, 1. Juni 2017 Endgültiges Ergebnis der Namentlichen Abstimmung Nr. 11 Beschlussempfehlung des Innenausschuss (4. Ausschuss) zu dem Antrag der Abgeordneten Luise Amtsberg, Omid Nouripour, Volker Beck (Köln), weiterer Abgeordneter und der Fraktion BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN Abschiebung nach Afghanistan - Drucksache 18/12099 und 18/12414 - Abgegebene Stimmen insgesamt: 561 Nicht abgegebene Stimmen: 69 Ja-Stimmen: 439 Nein-Stimmen: 108 Enthaltungen: 14 Ungültige: 0 Berlin, den 02.06.2017 Beginn: 23:17 Ende: 23:19 Seite: 1 Seite: 2 Seite: 2 CDU/CSU Name Ja Nein Enthaltung Ungült. Nicht abg. Stephan Albani X Katrin Albsteiger X Peter Altmaier X Artur Auernhammer X Dorothee Bär X Thomas Bareiß X Norbert Barthle X Günter Baumann X Maik Beermann X Manfred Behrens (Börde) X Veronika Bellmann X Sybille Benning X Dr. André Berghegger X Dr. Christoph Bergner X Ute Bertram X Peter Beyer X Steffen Bilger X Clemens Binninger X Peter Bleser X Dr. Maria Böhmer X Wolfgang Bosbach X Norbert Brackmann X Klaus Brähmig X Michael Brand X Dr. Reinhard Brandl X Helmut Brandt X Dr. Ralf Brauksiepe X Dr. Helge Braun X Heike Brehmer X Ralph Brinkhaus X Cajus Caesar X Gitta Connemann X Alexandra Dinges-Dierig X Alexander Dobrindt X Michael Donth X Thomas Dörflinger X Marie-Luise Dött X Hansjörg Durz X Iris Eberl X Jutta Eckenbach X Dr. Bernd Fabritius X Hermann Färber X Uwe Feiler X Dr. Thomas Feist X Enak Ferlemann X Ingrid Fischbach X Dirk Fischer (Hamburg) X Axel E. Fischer (Karlsruhe-Land) X Dr. Maria Flachsbarth X Klaus-Peter Flosbach X Seite: 3 CDU/CSU Name Ja Nein Enthaltung Ungült. -

Deutscher Bundestag

Plenarprotokoll 14/171 Deutscher Bundestag Stenographischer Bericht 171. Sitzung Berlin, Freitag, den 18. Mai 2001 Inhalt: Zusatztagesordnungspunkt 13: Fraktion der CDU/CSU: EU-Richtlini- envorschlag zur Gewährung vorüber- Erste Beratung des von den Abgeordneten gehenden Schutzes im Falle eines Alfred Hartenbach, Hermann Bachmaier, Massenzustroms überarbeiten weiteren Abgeordneten und der Fraktion (Drucksache 14/5754) . 16734 A der SPD sowie den Abgeordneten Volker Beck (Köln), Grietje Bettin, weiteren Ab- in Verbindung mit geordneten und der Fraktion des BÜND- NISSES 90/DIE GRÜNEN eingebrachten Entwurfs eines Gesetzes zur Modernisie- Zusatztagesordnungspunkt 8: rung des Schuldrechts (Drucksache 14/6040) . 16719 A Antrag der Abgeordneten Ulla Jelpke, Carsten Hübner, weiterer Abgeordneter und Dr. Herta Däubler-Gmelin, Bundesministerin der Fraktion der PDS: EU-Richtlinienvor- BMJ . 16719 B schlag zu Mindeststandards in Asylver- Ronald Pofalla CDU/CSU . 16721 B fahren ist ein wichtiger Schritt für einen wirksamen Flüchtlingsschutz in Europa Volker Beck (Köln) BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜ- (Drucksache 14/6050) . 16734 B NEN . 16723 C Erwin Marschewski (Recklinghausen) Rainer Funke F.D.P. 16725 C CDU/CSU . 16734 C Dr. Evelyn Kenzler PDS . 16727 C Otto Schily, Bundesminister BMI . 16735 D Dirk Manzewski SPD . 16728 B Dr. Max Stadler F.D.P. 16738 C Dr. Andreas Birkmann, Minister (Thüringen) 16730 B Ulla Jelpke PDS . 16739 B Alfred Hartenbach SPD . 16732 A Marieluise Beck (Bremen) BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN . 16740 B Ulla Jelpke PDS . 16742 A Tagesordnungspunkt 15: Dr. Hans-Peter Uhl CDU/CSU . 16742 D a) Antrag der Abgeordneten Wolfgang Bosbach, Erwin Marschewski (Reck- Rüdiger Veit SPD . 16744 D linghausen), weiterer Abgeordneter und Erwin Marschewski (Recklinghausen) der Fraktion der CDU/CSU: EU-Richt- CDU/CSU . -

Auszug Aus Dem Plenarprotokoll 18/155

Textrahmenoptionen: 16 mm Abstand oben Plenarprotokoll 18/155 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 155. Sitzung Berlin, Donnerstag, den 18. Februar 2016 Inhalt: Glückwünsche zum Geburtstag der Abgeord- Dr. Gerhard Schick (BÜNDNIS 90/ neten Dr. Ernst Dieter Rossmann, Bernhard DIE GRÜNEN) ................... 15214 A Schulte-Drüggelte, Dr. Karl Lamers und Christian Petry (SPD) .................. 15215 B Alois Gerig .......................... 15201 A Dr. Frank Steffel (CDU/CSU) ............ 15216 D Erweiterung und Abwicklung der Tagesord- nung. 15201 B Absetzung der Tagesordnungspunkte 5 und Zusatztagesordnungspunkt 2: 14. 15201 D Antrag der Abgeordneten Monika Lazar, Luise Nachträgliche Ausschussüberweisungen ... 15202 A Amtsberg, Volker Beck (Köln), weiterer Abge- ordneter und der Fraktion BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN: Demokratie stärken – Dem Hass Tagesordnungspunkt 4: keine Chance geben Drucksache 18/7553 ................... 15218 B Erste Beratung des von der Bundesregie- rung eingebrachten Entwurfs eines Ersten Dr. Anton Hofreiter (BÜNDNIS 90/ Gesetzes zur Novellierung von Finanz- DIE GRÜNEN) ..................... 15218 B marktvorschriften auf Grund europäischer Marian Wendt (CDU/CSU) .............. 15219 D Rechtsakte (Erstes Finanzmarktnovellie- rungsgesetz – 1. FiMaNoG) Katja Kipping (DIE LINKE) ............ 15221 D Drucksache 18/7482 ................... 15202 C Uli Grötsch (SPD) ..................... 15223 C Dr. Michael Meister, Parl. Staatssekretär Dr . Volker Ullrich (CDU/CSU) ........... 15224 D BMF ............................ -

Plenarprotokoll 16/190

Plenarprotokoll 16/190 Deutscher Bundestag Stenografischer Bericht 190. Sitzung Berlin, Donnerstag, den 27. November 2008 Inhalt: Nachträgliche Ausschussüberweisungen . 20439 A Peer Steinbrück, Bundesminister BMF . 20455 A Karl-Georg Wellmann (CDU/CSU) . 20457 C Tagesordnungspunkt IV: Dr. Hermann Otto Solms (FDP) . 20458 C – Zweite und dritte Beratung des von der Bundesregierung eingebrachten Entwurfs Dr. Peter Ramsauer (CDU/CSU) . 20459 D eines Gesetzes zur Reform des Erbschaft- Dr. Hermann Otto Solms (FDP) . 20460 C steuer- und Bewertungsrechts (Erb- schaftsteuerreformgesetz – ErbStRG) Florian Pronold (SPD) . 20461 A (Drucksachen 16/7918, 16/8547, 16/11075, Dr. Hermann Otto Solms (FDP) . 20461 C 16/11107) . 20439 B Otto Bernhardt (CDU/CSU) . 20462 A – Bericht des Haushaltsausschusses gemäß § 96 der Geschäftsordnung Volker Beck (Köln) (BÜNDNIS 90/ (Drucksache 16/11085) . 20439 B DIE GRÜNEN) . 20462 C Florian Pronold (SPD) . 20439 D Dirk Niebel (FDP) . 20463 A Dr. h. c. Hans Michelbach Dirk Niebel (FDP) . 20465 A (CDU/CSU) . 20440 C Otto Bernhardt (CDU/CSU) . 20465 C Dr. Volker Wissing (FDP) . 20442 D Namentliche Abstimmungen . .2046 . .5 . D,. 20466 A Carl-Ludwig Thiele (FDP) . 20443 B Albert Rupprecht (Weiden) Ergebnisse . .2046 . .7 . D,. 20470 A (CDU/CSU) . 20445 C Carl-Ludwig Thiele (FDP) . 20446 C Tagesordnungspunkt II (Fortsetzung): Dr. Peter Ramsauer (CDU/CSU) . 20446 D a) Zweite Beratung des von der Bundesregie- Carl-Ludwig Thiele (FDP) . 20447 D rung eingebrachten Entwurfs eines Geset- zes über die Feststellung des Bundes- Florian Pronold (SPD) . 20448 B haushaltsplans für das Haushaltsjahr 2009 (Haushaltsgesetz 2009) Dr. Barbara Hendricks (SPD) . 20448 C (Drucksachen 16/9900, 16/9902) . 20466 B Dr. Barbara Höll (DIE LINKE) . -

Deutscher Bundestag Antrag

Deutscher Bundestag Drucksache 18/2618 18. Wahlperiode 24.09.2014 Antrag der Abgeordneten Tom Koenigs, Annalena Baerbock, Marieluise Beck (Bremen), Dr. Franziska Brantner, Agnieszka Brugger, Uwe Kekeritz, Dr. Tobias Lindner, Omid Nouripour, Cem Özdemir, Claudia Roth (Augsburg), Manuel Sarrazin, Dr. Frithjof Schmidt, Jürgen Trittin, Doris Wagner, Luise Amtsberg, Volker Beck (Köln), Katja Keul, Renate Künast, Monika Lazar, Irene Mihalic, Dr. Konstantin von Notz und der Fraktion BÜNDNIS 90/DIE GRÜNEN Menschenrechtsförderung stärken – Gesetzliche Grundlage für Deutsches Institut für Menschenrechte schaffen Der Bundestag wolle beschließen: I. Der Deutsche Bundestag stellt fest: Im Dezember 2000 wurde das Deutsche Institut für Menschenrechte (DIMR) durch interfraktionellen Beschluss des Bundestages ins Leben gerufen. Es arbeitet seit März 2001 nun schon mehr als 13 Jahre äußerst erfolgreich für den Schutz der Men- schenrechte in und durch Deutschland. Eine Bestätigung seines wertvollen Beitrages zum Menschenrechtsschutz spiegelt sich in den stetig gestiegenen Erwartungen von Politik, Zivilgesellschaft und inter- nationalen Organisationen an das Institut wider. So zählen zu den thematischen Schwerpunkten des Instituts mittlerweile so unter- schiedliche Themen wie der Schutz vor Diskriminierung, wirtschaftliche Menschen- rechte, menschenrechtliche Anforderungen an die Sicherheitspolitik, zeitgenössi- sche Formen der Sklaverei, Menschenrechte von Flüchtlingen und Migrantinnen und Migranten und Menschenrechte und Entwicklungszusammenarbeit. 2009