Pat Arrowsmith Interview After Hiroshima Project 28Th April 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The English Catholic New Left: Battling the Religious Establishment and the Politics of the Cold War

social sciences $€ £ ¥ Article The English Catholic New Left: Battling the Religious Establishment and the Politics of the Cold War Jay P. Corrin College of General Studies, Boston University, Boston, MA 02215, USA; [email protected] Received: 5 March 2018; Accepted: 30 March 2018; Published: 8 April 2018 Abstract: In the 1960s there appeared in England a group of young university educated Catholics who sought to merge radical Catholic social teachings with the ideas of Karl Marx and the latest insights of European and American sociologists and literary theorists. They were known as the English Catholic New Left (ECNL). Under the inspiration of their Dominican mentors, they launched a magazine called Slant that served as the vehicle for publishing their ideas about how Catholic theology along with the Social Gospels fused with neo-Marxism could bring a humanistic socialist revolution to Britain. The Catholic Leftists worked in alliance with the activists of the secular New Left Review to achieve this objective. A major influence on the ECNL was the Marxist Dominican friar Laurence Bright and Herbert McCabe, O. P. Slant took off with great success when Sheed and Ward agreed to publish the journal. Slant featured perceptive, indeed at times brilliant, cutting-edge articles by the Catholic Left’s young Turks, including Terry Eagleton, Martin Redfern, Bernard Sharratt, and Angela and Adrian Cunningham, among others. A major target of the Slant project was the Western Alliance’s Cold War strategy of nuclear deterrence, which they saw to be contrary to Christian just war theory and ultimately destructive of humankind. Another matter of concern for the Slant group was capitalist imperialism that ravaged the underdeveloped world and was a major destabilizing factor for achieving world peace and social equality. -

In My Lifetime - the Film’S Mission

1 In My Lifetime - The Film’s Mission http://thenuclearworld.org/category/in-my-lifetime/ This film is meant to be a wakeup call for humanity, to help develop an understanding of the realities of the nuclear weapon, to explore ways of presenting the answers for “a way beyond” and to facilitate a dialogue moving towards resolution of this Gordian knot of nuclear weapons gripping the world. The documentary’s characters are the narrative voices, interwoven with highly visual sequences of archival and contemporary footage and animation. The story is a morality play, telling the struggle waged over the past six and half decades with the last act yet to be determined, of trying to find what is “the way beyond?” Director’s Statement “In My Lifetime” takes on the complex realities of “the nuclear world”, and searches internationally for an answer to the question is there a Way Beyond? This documentary is part wake up call, part challenge for people to engage with the issue of ridding the world of the most destructive weapon ever invented. In February 2008, I began a journey to film and report on the story of the inner workings of the nuclear world. There has been a re-emergence of the realization that a world with nuclear weapons, including a proliferation of fissile nuclear materials, is a very dangerous place. Of course this realization has been known since the creation of the atomic bomb. It continues to be a struggle which has not been resolved. 2 This is a very complex issue with many voices, speaking from many perspectives, representing the forces and entrenched institutions in the nuclear states, not to speak of the rest of the world’s nations some of them with nuclear power capable of producing their own fissile materials and now there is the danger of so called “non-state actors”, who want to get their hands on the nuclear fissile materials necessary to create nuclear weapons. -

University of Edinburgh 1986

A eoomi bnent To C<mpaign: a sociological study of C.N.D. John Mattausch Ph.D. university of Edinburgh 1986 Declaration This thesis has been composed by myself and the research on which it is based was my own work. ul~ 1 V E1t~lTY OF EDINBURGH ABSTRACT OF THESIS (Regulation 7.9) John Mattausch Name a/Candidate .............................................................................................................................................................. .. 8 Savile Terrace, Edinburgh Address ................................................................................................................................................................................ .. ph.D. June 1986 Degree ....................................................................................................... Date ................................................................ To Title. a/ThesIs. .......................................................................................................................................................................A Corrmi trnent Ccmpaign: a sociological study of C.N.D. Na. a/wards in the main text a/Thesis .... 8.a*'125 ............................................................................................................... In this sociological study of the British Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, I seek to explain how social factors influence the form which disarmament protesting takes and how they also determine the Campaign's socially unrepresentative basis of support. Following the -

The Beginning Since Atomic Weapons Were First Used in 1945 It Is Odd That There Was No Big Campaign Against Them Until 1957

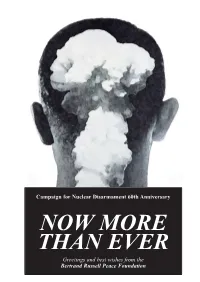

13.RussellCND_Template.qxd 15/02/2018 10:47 Page 14 Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament 60th Anniversary NOW MORE THAN EVER Greetings and best wishes from the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation 14.DuffCND_Template.qxd 15/02/2018 10:48 Page 9 93 The Beginning Since atomic weapons were first used in 1945 it is odd that there was no big campaign against them until 1957. There CND 195865 had been one earlier attempt at a campaign, in 1954, when Britain was proceeding to make her own HBombs. Fourteen years later, Anthony Wedgwood Benn, who was one who led the Anti HBomb Petition then, was refusing the CND Aldermaston marchers permission to stop and hold a meeting on ministry land, outside the factory near Burghfield, Berks, making, warheads for Polaris submarine missiles. Autres temps, autres moeurs. Peggy Duff There were two reasons why it suddenly zoomed up in 1957.The first stimulus was the HBomb tests at Christmas Island in the Pacific. It was these that translated the committee formed in Hampstead in North London into a national campaign, and which brought into being a number of local committees around Britain which predated CND itself — in Oxford, in Reading, in Kings Lynn and a number of other places. Tests were a constant and very present reminder of the menace of nuclear weapons, affecting especially the health of children, and of babies yet unborn. Fallout seemed something uncanny, unseen and frightening. The Christmas Island tests, because they were British tests, at last roused opinion in Britain. The second reason was the failure of the Labour Party in the autumn of 1957 to pass, Peggy Duff was the first as expected, a resolution in favour of secretary of the Campaign unilateral abandonment of nuclear weapons for Nuclear Disarmament. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. Michael Gove, 15 November 2010, Hansard Parliamentary Debates,column 634, www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201011. 2. Ofsted made a statement to this effect on 11 July 2004 which was reported on by the BBC (http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/education/3884087.stm) and The Telegraph (www.telegraph.co.uk/education/educationnews). 3. There is a growing literature on the Falklands War, most of which does not contextualise the conflict in terms of the British Empire despite the jingoistic use of imperial ideology during the conflict. 4. Bill Schwarz (2011) The White Man’s World, Memories of Empire, 1 (Oxford University Press), p. 6. 5. Avner Offer (1993) ‘The British Empire, 1870–1914: A Waste of Money?’, The Economic History Review 46, no. 2, 215–38. 6. Bernard Porter (2004) The Absent-Minded Imperialists: Empire, Society, and Culture in Britain (Oxford University Press); John M. MacKenzie (1984) Pro- paganda and Empire: The Manipulation of British Public Opinion, 1880–1960 (Manchester University Press). 7. Alan Sked (1987) Britain’s Decline: Problems and Perspectives (Oxford: Basil Blackwell). 8. Catherine Hall and Sonya Rose (2006) ‘Introduction: Being at Home with the Empire’, in Catherine Hall and Sonya O. Rose (eds), At Home with the Empire: Metropolitan Culture and the Imperial World (Cambridge University Press). 9. Bill Schwarz (1996) ‘ “The Only White Man in There”: The Re-Racialisation of England, 1956–1968’, Race and Class 38, no. 1, 65. 10. Stuart Ward (ed.) (2001) British Culture and the End of Empire,Studiesin Imperialism (Manchester University Press). 11. Stuart Ward (2001) ‘Introduction’, in idem (ed.), British Culture and the End of Empire (Manchester University Press), p. -

A Life in the Shadow of the Bomb

A Life in the Shadow of the Bomb I am a child of the atomic age. The atomic bomb, that is, the threat of nuclear war and mass destruction, has been in my consciousness—sometimes in the background but frequently in the foreground—nearly all of my life. I was born on August 9, 1945 at the Lying Inn Hospital of the University of Chicago, the day that the second atomic bomb was dropped in Japan on the city of Nagasaki, killing tens of thousands of people. My birthplace, the U of C, was also the birthplace of the atomic bomb, which had been conceived there a couple of years before. Enrico Fermi and other scientists in the Manhattan Project carried out the first chain reaction on December 2, 1942 in a secret laboratory hidden in the university’s football stadium. Of course, when I let out my first shriek at the shock of birth and the awakening into life, I knew nothing of any of that. I first became conscious of the issue of nuclear war when I was eight years old. My parents had moved to Whittier, California, where my father was to manage a Co-op Grocery Store. The local public elementary school that I attended held “duck-and-cover” drills and we students had to get under our desks and put our hands over our heads. We were told this would protect us in the event of a nuclear attack. A duck-and-cover pubic service announcement of the era shows, among other scenarios, an elementary school class much like mine. -

The British Peace Movement and Socialist Change*

THE BRITISH PEACE MOVEMENT AND SOCIALIST CHANGE* Richard Taylor In the post-war period the largest, and arguably the most significant, mobilisation of radical forces in Britain has taken place around the issue of nuclear disarmament. From the late-1950s to the mid-1960s, and again from the late-1970s to the time of writing, the peace movement has been a dominant force and has succeeded in bringing together a diverse coalition in opposition to British possession of nuclear weapons. This paper has two primary purposes: first, to examine the politics of the peace movement of 1958 to 1965 and to analyse the reasons for its ultimate failure; second, to argue, on the basis of the experience of that period, that for the peace movement to succeed in the future there must be a linkage at a number of levels between the movement for peace and the movement for specifically socialist change. The focus is thus upon the various political strategies adopted by the earlier movement, but always within the context of the implications this experience has for the contemporary movement. The persistent and fundamental problem of the movement since its inception has been its inability to translate its undoubted popular appeal into real, tangible achievement. Although the movement has had a very considerable impact upon public opinion, and thus, arguably, indirectly upon formal political structures and policies, it is quite clear that its central objectives have not been achieved. Moreover, the deterioration of the Cold War climate in the 1980s and the increasing escalation of the arms race both testify to the movement's lack of success. -

View / Open Thesis Final-Dorland.Pdf

CREATIVE NONVIOLENT ACTION: LEVERAGING THE INTERSECTIONS OF ART, PROTEST, AND INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATIONS TECHNOLOGY FOR SOCIAL CHANGE by EMMA DORLAND A THESIS Presented to the Department of Spanish and the Robert D. Clark Honors College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts June 2015 Acknowledgements I would like to formally acknowledge and thank my Advisory Committee for their commitment to seeing me through this process. These professors have generously given of their time and expertise to facilitate my growth and my completion of this substantial project. Thank you to Professor Analisa Taylor, who has coached and guided me, consistently offering insightful critique of my work and challenging me to develop my thinking and express myself clearly. Her expertise in the humanities and in the writing process has made me a stronger writer and a more analytical scholar. Thank you to Professor Kiersten Muenchinger for lending her keen eye to this project and for helping me to build my capacity for creativity by extending her most perceptive feedback. Thank you to Professor Monique Balbuena for serving as a reliable resource and for urging me to develop a more amplified perspective and complex argument from the outset of this project through to its completion. I am incredibly appreciative of each of these professors for their words of encouragement and commitment to my success. In addition, I would like to thank Dianne Torres for her consistent support throughout my writing of this thesis and all of my college years. I am deeply grateful for her caring guidance each step of the way. -

At 55, the Peace Symbol Endures. Peace, Not So Much by Bill Berkowitz

At 55, The Peace Symbol Endures. Peace, Not So Much By Bill Berkowitz (Dedicated to my grandson Alton Theodore Berkowitz-Gosselin and to all the children who will be inheriting a world hungry for peace.) The peace symbol is arguably the world’s most widely recognized protest symbol. In 2008, on the occasion of its fiftieth birthday, BBC News noted that the peace symbol has been “adapted, attacked and commercialized.” At fifty-five, the peace symbol remains a cultural icon, but as it ages, is it more than that? Originally created as a symbol for the British anti-nuclear movement, it is now ubiquitous: appearing at thousands of anti-nuclear and anti-war protests; adorning posters, buttons, badges, and peace flags; becoming a fixture on postal stamps; and, decorating clothing, beach towels, jewelry, and people’s skin. “Walk through the halls of any elementary or junior high school and you'll see the peace sign all over in kids' fashion, young girls especially - t-shirts, shorts, shoes, backpacks, earrings, pendants,” Peace Talks radio pointed out on its website a while back. The peace symbol was first seen in public on Good Friday in 1958 when thousands of British anti-nuclear campaigners – organized by the Direct Action Committee Against Nuclear War (DAC) and the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) -- marched 50 miles from London's Trafalgar Square to the weapons factory at Aldermaston. When Gerald Holtom, a British designer and former World War II conscientious objector, sat down at his drawing board fifty-five years ago, he was in almost total despair. -

European Peace Movements During the Cold War and Their Elective Affinities

This is a repository copy of A quantum of solace? European peace movements during the Cold War and their elective affinities. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/74457/ Article: Ziemann, Benjamin (2009) A quantum of solace? European peace movements during the Cold War and their elective affinities. Archiv für Sozialgeschichte , 49. pp. 351-389. ISSN 0066-6505 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Archiv für Sozialgeschichte 49, 2009 351 Benjamin Ziemann A Quantum of Solace? European Peace Movements during the Cold War and their Elective Affinities Peace movements can be defined as social movements that aim to protest against the per- ceived dangers of political decision-making about armaments.1 During the Cold War, the foremost aim of peace protests was to ban atomic weapons and to alert the public about the dangers of these new powerful means of destruction. -

The Public Health Crisis in Occupied Germany

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 03/21/2015, SPi THE PERILS OF PEACE OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 03/21/2015, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 03/21/2015, SPi The Perils of Peace The Public Health Crisis in Occupied Germany JESSICA REINISCH 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 03/21/2015, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Jessica Reinisch 2013 The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2013 Impression: 1 Some rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise, for commercial purposes without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press. This is an open access publication. Except where otherwise noted, this work is distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND), a copy of which is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by- nc-nd/4.0/ Enquiries concerning use outside the scope of the licence terms should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the above address. British Library Cataloguing in Publication data Data available ISBN 978–0–19–966079–7 Printed in Great Britain by MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King’s Lynn Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

Nuclear Disarmament and the Making of National Identity in Scotland and Wales

NB: The online application system was not accepting PDF files, hence this Word Version Nations of Peace: Nuclear Disarmament and the Making of National Identity in Scotland and Wales This article uses the Scottish and Welsh Councils for Nuclear Disarmament as windows into the relationship between peace and nationalism in Scotland and Wales in the late 1950s and early 60s. From one perspective, it challenges histories of peace movements in Britain, which have laboured under approaches and assumptions centred on London. From an- other, it demonstrates the role of movements for nuclear disarmament in the emergence of a ‘left of centre’ nationalism in Scotland and Wales. Although these movements were constituents of the British Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND), their nationalism evolved as the threat from nuclear weapons to Scotland and Wales came to be seen as distinctive and was interpreted through lenses of local culture and tradition. The movements contributed to ‘the making of national identity’ by providing a channel through activists could ‘nationalise’ and galvanise Scottish and Welsh Christianity, folk and socialism in particular. It was through the movements that activists articulated and promoted Scotland and Wales as sovereign nations of peace, with an international outlook separate from that of Britain. Key Words: Nuclear Disarmament; Nationalism; Peace The movements for nuclear disarmament in Scotland and Wales contributed to the ‘nationalisation’ of local forms of idealism and activism in those countries. As Scottish and Welsh activists drew upon local cultures and traditions to construct and imagine civil societies free from the threat of the Cold War and nuclear weapons, they brought them into a national context that was rich in potential for nationalist parties and politics.1 The Scottish and Welsh movements were a means not only by which local cultures in Scotland and Wales could be homogenised and defined in favour of national sover- eignty, but also by which they could be fortified and defined against Britain.