University of Edinburgh 1986

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The English Catholic New Left: Battling the Religious Establishment and the Politics of the Cold War

social sciences $€ £ ¥ Article The English Catholic New Left: Battling the Religious Establishment and the Politics of the Cold War Jay P. Corrin College of General Studies, Boston University, Boston, MA 02215, USA; [email protected] Received: 5 March 2018; Accepted: 30 March 2018; Published: 8 April 2018 Abstract: In the 1960s there appeared in England a group of young university educated Catholics who sought to merge radical Catholic social teachings with the ideas of Karl Marx and the latest insights of European and American sociologists and literary theorists. They were known as the English Catholic New Left (ECNL). Under the inspiration of their Dominican mentors, they launched a magazine called Slant that served as the vehicle for publishing their ideas about how Catholic theology along with the Social Gospels fused with neo-Marxism could bring a humanistic socialist revolution to Britain. The Catholic Leftists worked in alliance with the activists of the secular New Left Review to achieve this objective. A major influence on the ECNL was the Marxist Dominican friar Laurence Bright and Herbert McCabe, O. P. Slant took off with great success when Sheed and Ward agreed to publish the journal. Slant featured perceptive, indeed at times brilliant, cutting-edge articles by the Catholic Left’s young Turks, including Terry Eagleton, Martin Redfern, Bernard Sharratt, and Angela and Adrian Cunningham, among others. A major target of the Slant project was the Western Alliance’s Cold War strategy of nuclear deterrence, which they saw to be contrary to Christian just war theory and ultimately destructive of humankind. Another matter of concern for the Slant group was capitalist imperialism that ravaged the underdeveloped world and was a major destabilizing factor for achieving world peace and social equality. -

The Beginning Since Atomic Weapons Were First Used in 1945 It Is Odd That There Was No Big Campaign Against Them Until 1957

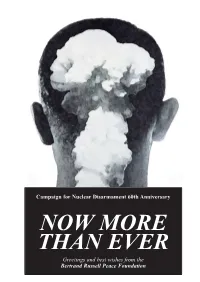

13.RussellCND_Template.qxd 15/02/2018 10:47 Page 14 Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament 60th Anniversary NOW MORE THAN EVER Greetings and best wishes from the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation 14.DuffCND_Template.qxd 15/02/2018 10:48 Page 9 93 The Beginning Since atomic weapons were first used in 1945 it is odd that there was no big campaign against them until 1957. There CND 195865 had been one earlier attempt at a campaign, in 1954, when Britain was proceeding to make her own HBombs. Fourteen years later, Anthony Wedgwood Benn, who was one who led the Anti HBomb Petition then, was refusing the CND Aldermaston marchers permission to stop and hold a meeting on ministry land, outside the factory near Burghfield, Berks, making, warheads for Polaris submarine missiles. Autres temps, autres moeurs. Peggy Duff There were two reasons why it suddenly zoomed up in 1957.The first stimulus was the HBomb tests at Christmas Island in the Pacific. It was these that translated the committee formed in Hampstead in North London into a national campaign, and which brought into being a number of local committees around Britain which predated CND itself — in Oxford, in Reading, in Kings Lynn and a number of other places. Tests were a constant and very present reminder of the menace of nuclear weapons, affecting especially the health of children, and of babies yet unborn. Fallout seemed something uncanny, unseen and frightening. The Christmas Island tests, because they were British tests, at last roused opinion in Britain. The second reason was the failure of the Labour Party in the autumn of 1957 to pass, Peggy Duff was the first as expected, a resolution in favour of secretary of the Campaign unilateral abandonment of nuclear weapons for Nuclear Disarmament. -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. Michael Gove, 15 November 2010, Hansard Parliamentary Debates,column 634, www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201011. 2. Ofsted made a statement to this effect on 11 July 2004 which was reported on by the BBC (http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/education/3884087.stm) and The Telegraph (www.telegraph.co.uk/education/educationnews). 3. There is a growing literature on the Falklands War, most of which does not contextualise the conflict in terms of the British Empire despite the jingoistic use of imperial ideology during the conflict. 4. Bill Schwarz (2011) The White Man’s World, Memories of Empire, 1 (Oxford University Press), p. 6. 5. Avner Offer (1993) ‘The British Empire, 1870–1914: A Waste of Money?’, The Economic History Review 46, no. 2, 215–38. 6. Bernard Porter (2004) The Absent-Minded Imperialists: Empire, Society, and Culture in Britain (Oxford University Press); John M. MacKenzie (1984) Pro- paganda and Empire: The Manipulation of British Public Opinion, 1880–1960 (Manchester University Press). 7. Alan Sked (1987) Britain’s Decline: Problems and Perspectives (Oxford: Basil Blackwell). 8. Catherine Hall and Sonya Rose (2006) ‘Introduction: Being at Home with the Empire’, in Catherine Hall and Sonya O. Rose (eds), At Home with the Empire: Metropolitan Culture and the Imperial World (Cambridge University Press). 9. Bill Schwarz (1996) ‘ “The Only White Man in There”: The Re-Racialisation of England, 1956–1968’, Race and Class 38, no. 1, 65. 10. Stuart Ward (ed.) (2001) British Culture and the End of Empire,Studiesin Imperialism (Manchester University Press). 11. Stuart Ward (2001) ‘Introduction’, in idem (ed.), British Culture and the End of Empire (Manchester University Press), p. -

The British Peace Movement and Socialist Change*

THE BRITISH PEACE MOVEMENT AND SOCIALIST CHANGE* Richard Taylor In the post-war period the largest, and arguably the most significant, mobilisation of radical forces in Britain has taken place around the issue of nuclear disarmament. From the late-1950s to the mid-1960s, and again from the late-1970s to the time of writing, the peace movement has been a dominant force and has succeeded in bringing together a diverse coalition in opposition to British possession of nuclear weapons. This paper has two primary purposes: first, to examine the politics of the peace movement of 1958 to 1965 and to analyse the reasons for its ultimate failure; second, to argue, on the basis of the experience of that period, that for the peace movement to succeed in the future there must be a linkage at a number of levels between the movement for peace and the movement for specifically socialist change. The focus is thus upon the various political strategies adopted by the earlier movement, but always within the context of the implications this experience has for the contemporary movement. The persistent and fundamental problem of the movement since its inception has been its inability to translate its undoubted popular appeal into real, tangible achievement. Although the movement has had a very considerable impact upon public opinion, and thus, arguably, indirectly upon formal political structures and policies, it is quite clear that its central objectives have not been achieved. Moreover, the deterioration of the Cold War climate in the 1980s and the increasing escalation of the arms race both testify to the movement's lack of success. -

Pat Arrowsmith Interview After Hiroshima Project 28Th April 2015

Pat Arrowsmith Interview After Hiroshima Project 28th April 2015 Interviewee: Pat Arrowsmith (PA) born 02.03.1930 Interviewer(s): Katie Nairne & Ruth Dewa (Interviewer) (0.00) Interviewer: Um so my name is Katie Nairne, N-A-I-R-N-E, um and I'm interviewing, er could you say your name for the tape please? PA: Pat Arrowsmith. Interviewer: How's that spelt? PA: Well, Pat is P-A-T, it's not short for Patricia, I was christened Pat by two bishops, one of whom arrived late for the event, and Arrowsmith as, most inappropriate for a peace activist, 'arrow' as the arrows that you shoot, and 'smith' - all the same word, Arrowsmith. Interviewer: Thank you. And please could I get you to say your date of birth for the tape? PA: 2nd March, 1930. Interviewer: Thank you. Um and I'm interviewing Pat for the After Hiroshima Project, er for London Bubble Theatre Company. Um so Pat, just to start in 1945, um what are your memories of the Second World War? PA: Um I don't have any (1.00) very grisly memories, my father was a vicar who travelled around doing dif, different parishes, and happenstance in 1939 when World War Two broke out he was scheduled to go to Torquay anyway, so we moved from where we had been living er further up the coast at Weston-super-Mare to Torquay, in time to arrive there for the outbreak of er, fairly soon after we got there, World War Two, which er was er... Oh well no wait a moment, we got there in 1939, ‘40. -

European Peace Movements During the Cold War and Their Elective Affinities

This is a repository copy of A quantum of solace? European peace movements during the Cold War and their elective affinities. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/74457/ Article: Ziemann, Benjamin (2009) A quantum of solace? European peace movements during the Cold War and their elective affinities. Archiv für Sozialgeschichte , 49. pp. 351-389. ISSN 0066-6505 Reuse Unless indicated otherwise, fulltext items are protected by copyright with all rights reserved. The copyright exception in section 29 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 allows the making of a single copy solely for the purpose of non-commercial research or private study within the limits of fair dealing. The publisher or other rights-holder may allow further reproduction and re-use of this version - refer to the White Rose Research Online record for this item. Where records identify the publisher as the copyright holder, users can verify any specific terms of use on the publisher’s website. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Archiv für Sozialgeschichte 49, 2009 351 Benjamin Ziemann A Quantum of Solace? European Peace Movements during the Cold War and their Elective Affinities Peace movements can be defined as social movements that aim to protest against the per- ceived dangers of political decision-making about armaments.1 During the Cold War, the foremost aim of peace protests was to ban atomic weapons and to alert the public about the dangers of these new powerful means of destruction. -

The Public Health Crisis in Occupied Germany

OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 03/21/2015, SPi THE PERILS OF PEACE OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 03/21/2015, SPi OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 03/21/2015, SPi The Perils of Peace The Public Health Crisis in Occupied Germany JESSICA REINISCH 1 OUP CORRECTED PROOF – FINAL, 03/21/2015, SPi 3 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Jessica Reinisch 2013 The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2013 Impression: 1 Some rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise, for commercial purposes without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press. This is an open access publication. Except where otherwise noted, this work is distributed under the terms of a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence (CC BY-NC-ND), a copy of which is available at http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by- nc-nd/4.0/ Enquiries concerning use outside the scope of the licence terms should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the above address. British Library Cataloguing in Publication data Data available ISBN 978–0–19–966079–7 Printed in Great Britain by MPG Books Group, Bodmin and King’s Lynn Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

Nuclear Disarmament and the Making of National Identity in Scotland and Wales

NB: The online application system was not accepting PDF files, hence this Word Version Nations of Peace: Nuclear Disarmament and the Making of National Identity in Scotland and Wales This article uses the Scottish and Welsh Councils for Nuclear Disarmament as windows into the relationship between peace and nationalism in Scotland and Wales in the late 1950s and early 60s. From one perspective, it challenges histories of peace movements in Britain, which have laboured under approaches and assumptions centred on London. From an- other, it demonstrates the role of movements for nuclear disarmament in the emergence of a ‘left of centre’ nationalism in Scotland and Wales. Although these movements were constituents of the British Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND), their nationalism evolved as the threat from nuclear weapons to Scotland and Wales came to be seen as distinctive and was interpreted through lenses of local culture and tradition. The movements contributed to ‘the making of national identity’ by providing a channel through activists could ‘nationalise’ and galvanise Scottish and Welsh Christianity, folk and socialism in particular. It was through the movements that activists articulated and promoted Scotland and Wales as sovereign nations of peace, with an international outlook separate from that of Britain. Key Words: Nuclear Disarmament; Nationalism; Peace The movements for nuclear disarmament in Scotland and Wales contributed to the ‘nationalisation’ of local forms of idealism and activism in those countries. As Scottish and Welsh activists drew upon local cultures and traditions to construct and imagine civil societies free from the threat of the Cold War and nuclear weapons, they brought them into a national context that was rich in potential for nationalist parties and politics.1 The Scottish and Welsh movements were a means not only by which local cultures in Scotland and Wales could be homogenised and defined in favour of national sover- eignty, but also by which they could be fortified and defined against Britain. -

Roberts.Sophie Phd.Pdf

Northumbria Research Link Citation: Roberts, Sophie (2018) British Women Activists and the Campaigns against the Vietnam War, 1965-75. Doctoral thesis, Northumbria University. This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/id/eprint/40000/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/policies.html British Women Activists and the Campaigns against the Vietnam War, 1965-75 Sophie Roberts PhD 2018 British Women Activists and the Campaigns against the Vietnam War, 1965-75 Sophie Roberts A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Northumbria at Newcastle for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Research undertaken in the Faculty of Arts, Design and Social Sciences October 2018 Abstract This thesis makes an original contribution to the literature on anti-war protest in Britain by assessing the role of women activists in the movement against the Vietnam War. -

Public Diplomacy for the Nuclear Age: the United States, the United Kingdom, and the End of the Cold War

PUBLIC DIPLOMACY FOR THE NUCLEAR AGE: THE UNITED STATES, THE UNITED KINGDOM, AND THE END OF THE COLD WAR A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History By Anthony M. Eames, M.A. Washington, DC April 9, 2020 Copyright 2020 by Anthony M. Eames All Rights ReserveD ii PUBLIC DIPLOMACY FOR THE NUCLEAR AGE: THE UNITED STATES, THE UNITED KINGDOM, AND THE END OF THE COLD WAR Anthony M. Eames, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Kathryn Olesko, Ph.D., David Painter, Ph.D. ABSTRACT During the 1980s, public diplomacy campaigns on both sides of the Atlantic competed for moral, political, and scientific legitimacy in debates over arms control, the deployment of new missile systems, ballistic missile defense, and the consequences of nuclear war. The U.S. and U.K. governments, led respectively by Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, and backed by a network of think tanks and political organizations associated with the New Right, sought to win public support for a policy of Western nuclear superiority over the Soviet bloc. Transatlantic peace movement and scientific communities, in contrast, promoted the language and logic of arms reduction as an alternative to the arms race. Their campaigns produced new approaches for relating scientific knowledge and the voice of previously neglected groups such as women, racial minorities, and the poor, to the public debate to illuminate the detrimental effects of reliance on nuclear weapons for Western society. The conflict between these simultaneously domestic and transnational campaigns transformed the nature of diplomacy and public diplomacy, in which official and unofficial actors engaged transnational publics in order to win support for their policy preferences, emerged as an important complement to state-based institutional channels of international relations. -

Democracy – Growing Or Dying?

Editorial Democracy – Growing or Dying? This is the hundredth number of The Spokesman, so we are expected to have a birthday party. Nostalgia is in order at such events, and we have accordingly devoted quite a large part of this number to reproducing articles and features which involved us, with many of our readers, in a variety of campaigns to change things for the better. Sometimes these have succeeded, if only, say the sceptics, in provoking our old antagonists to find new ways to make them worse again. Sometimes they have failed, only to stiffen our resolve to try again, when times may be more propitious for their success. There are, of course, a number of key concerns which have continuously preoccupied us. There has been no possibility of forgetting, even temporarily, the desperate urgency of the struggle for peace and disarmament. It has been quite possible, but very regrettable, to forget the struggle for the widening and deepening of democracy, and this possibility has been amply brought into evidence by the progress of sundry statesmen, not to say less elevated tribunes of the people, some of whom have opted for popular emancipation, one at a time, me first. This kind of apostasy does discourage people, if only temporarily. If hope springs eternal, so too does the aspiration for effective power over the terms and conditions of our own lives. Politicians commonly tell us that the major social struggles are about power. ‘We need’ they say, ‘power to prevent the next war, or to save the environment from destruction, or to protect people from exploitation and domination.’ That is one way of putting it, but there are dangers wrapped up in it. -

Roberts, Sophie (2018) British Women Activists and the Campaigns Against the Vietnam War, 1965-75

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Northumbria Research Link Citation: Roberts, Sophie (2018) British Women Activists and the Campaigns against the Vietnam War, 1965-75. Doctoral thesis, Northumbria University. This version was downloaded from Northumbria Research Link: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/40000/ Northumbria University has developed Northumbria Research Link (NRL) to enable users to access the University’s research output. Copyright © and moral rights for items on NRL are retained by the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. Single copies of full items can be reproduced, displayed or performed, and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided the authors, title and full bibliographic details are given, as well as a hyperlink and/or URL to the original metadata page. The content must not be changed in any way. Full items must not be sold commercially in any format or medium without formal permission of the copyright holder. The full policy is available online: http://nrl.northumbria.ac.uk/policies.html British Women Activists and the Campaigns against the Vietnam War, 1965-75 Sophie Roberts PhD 2018 British Women Activists and the Campaigns against the Vietnam War, 1965-75 Sophie Roberts A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Northumbria at Newcastle for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Research undertaken in the Faculty of Arts, Design and Social Sciences October 2018 Abstract This thesis makes an original contribution to the literature on anti-war protest in Britain by assessing the role of women activists in the movement against the Vietnam War.