After Hiroshima Interview Transcript

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The English Catholic New Left: Battling the Religious Establishment and the Politics of the Cold War

social sciences $€ £ ¥ Article The English Catholic New Left: Battling the Religious Establishment and the Politics of the Cold War Jay P. Corrin College of General Studies, Boston University, Boston, MA 02215, USA; [email protected] Received: 5 March 2018; Accepted: 30 March 2018; Published: 8 April 2018 Abstract: In the 1960s there appeared in England a group of young university educated Catholics who sought to merge radical Catholic social teachings with the ideas of Karl Marx and the latest insights of European and American sociologists and literary theorists. They were known as the English Catholic New Left (ECNL). Under the inspiration of their Dominican mentors, they launched a magazine called Slant that served as the vehicle for publishing their ideas about how Catholic theology along with the Social Gospels fused with neo-Marxism could bring a humanistic socialist revolution to Britain. The Catholic Leftists worked in alliance with the activists of the secular New Left Review to achieve this objective. A major influence on the ECNL was the Marxist Dominican friar Laurence Bright and Herbert McCabe, O. P. Slant took off with great success when Sheed and Ward agreed to publish the journal. Slant featured perceptive, indeed at times brilliant, cutting-edge articles by the Catholic Left’s young Turks, including Terry Eagleton, Martin Redfern, Bernard Sharratt, and Angela and Adrian Cunningham, among others. A major target of the Slant project was the Western Alliance’s Cold War strategy of nuclear deterrence, which they saw to be contrary to Christian just war theory and ultimately destructive of humankind. Another matter of concern for the Slant group was capitalist imperialism that ravaged the underdeveloped world and was a major destabilizing factor for achieving world peace and social equality. -

1986 Peace Through Non-Alignment: the Case for British Withdrawal from NATO

Digital Archive digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org International History Declassified 1986 Peace Through Non-Alignment: The case for British withdrawal from NATO Citation: “Peace Through Non-Alignment: The case for British withdrawal from NATO,” 1986, History and Public Policy Program Digital Archive, Ben Lowe, Published by Verso, sponsored by The Campaign Group of Labor MP's, The Socialist Society, and the Campaign for Non-Alignment, 1986. http://digitalarchive.wilsoncenter.org/document/110192 Summary: Pamphlet arguing for British withdrawal from the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. It examines the origins of NATO, its role in U.S. foreign policy, its nuclear strategies, and its effect on British politics and national security. Original Language: English Contents: Scan of Original Document Ben Lowe is author of a book on NATO published in Spain as part of the campaign for Spanish withdrawal during the referendum of March 1986, La Cara Ocuita de fa OTAN; a contributor to Mad Dogs edited by Edward Thompson and Mary Kaldor; and a member of the Socialist Society, which has provided financial and research support for this pamphlet. Ben Lowe Peace through Non-Alignlllent The Case Against British Membership of NATO The Campaign Group of Labour MPs welcomes the publication of this pamphlet and believes that the arguments it contains are worthy of serious consideration. VERSO Thn Il11prlnt 01 New Left Books Contents First published 1986 Verso Editions & NLB F'oreword by Tony Benn and Jeremy Corbyn 15 Greek St, London WI Ben Lowe 1986 Introduction 1 ISBN 086091882 Typeset by Red Lion Setters 1. NATO and the Post-War World 3 86 Riversdale Road, N5 Printed by Wernheim Printers Forster Rd N17 Origins of the Alliance 3 America's Global Order 5 NATO's Nuclear Strategies 7 A Soviet Threat? 9 NA TO and British Politics 11 Britain's Strategic Role 15 Star Wars and Tension in NA TO 17 America and Europe's Future 19 2. -

Prosecuting Terrorism: the Old Bailey Versus Belmarsh by Clive Walker

Prosecuting terrorism: the Old Bailey versus Belmarsh by Clive Walker Consistent with his “war on terror” paradigm, President George W Bush asserted that “it is not enough to serve our enemies with legal papers” (State of the Union Address, January 20, 2004). In resonance with this view, the prime legal focus in the immediate aftermath of 9/11 was more upon Belmarsh rather than the Old Bailey – in other words, upon detention without trial and latterly on control orders rather than prosecutions. However, this era of executive action is fading in United Kingdom domestic law. The first part of this paper will examine the foundations for the reinvigoration of criminal justice. The second part will explore the present and future implications for criminal justice. THE PRIMACY OF CRIMINAL terrorism, or new police powers to investigate potential PROSECUTION crimes, notably, 28 day detention. Within the Counter- Terrorism Act 2008, its administrative innovations of The British Government might assert that the primacy notification and foreign travel restriction in Part IV are of criminal prosecution has been assured ever since the dependent upon criminal convictions, while Part III Diplock Report (Report of the Commission to consider enhances sentencing powers. legal procedures to deal with terrorist activities in Northern Ireland (Cmnd 5185, London, 1972)) plotted a The second indicator is the paucity of executive orders. path out of internment without trial and military Despite the apocalyptic analysis in 2007 of Jonathan Evans, predominance in Northern Ireland. But what happened the Director of the Security Service, that 2,000 suspects between 2001 and 2005 appeared to be a swing away from pose a threat to national security, there were just 15 prosecution. -

University of Edinburgh 1986

A eoomi bnent To C<mpaign: a sociological study of C.N.D. John Mattausch Ph.D. university of Edinburgh 1986 Declaration This thesis has been composed by myself and the research on which it is based was my own work. ul~ 1 V E1t~lTY OF EDINBURGH ABSTRACT OF THESIS (Regulation 7.9) John Mattausch Name a/Candidate .............................................................................................................................................................. .. 8 Savile Terrace, Edinburgh Address ................................................................................................................................................................................ .. ph.D. June 1986 Degree ....................................................................................................... Date ................................................................ To Title. a/ThesIs. .......................................................................................................................................................................A Corrmi trnent Ccmpaign: a sociological study of C.N.D. Na. a/wards in the main text a/Thesis .... 8.a*'125 ............................................................................................................... In this sociological study of the British Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, I seek to explain how social factors influence the form which disarmament protesting takes and how they also determine the Campaign's socially unrepresentative basis of support. Following the -

The Beginning Since Atomic Weapons Were First Used in 1945 It Is Odd That There Was No Big Campaign Against Them Until 1957

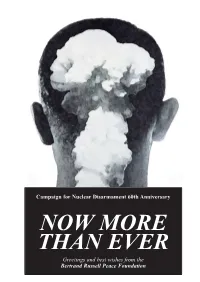

13.RussellCND_Template.qxd 15/02/2018 10:47 Page 14 Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament 60th Anniversary NOW MORE THAN EVER Greetings and best wishes from the Bertrand Russell Peace Foundation 14.DuffCND_Template.qxd 15/02/2018 10:48 Page 9 93 The Beginning Since atomic weapons were first used in 1945 it is odd that there was no big campaign against them until 1957. There CND 195865 had been one earlier attempt at a campaign, in 1954, when Britain was proceeding to make her own HBombs. Fourteen years later, Anthony Wedgwood Benn, who was one who led the Anti HBomb Petition then, was refusing the CND Aldermaston marchers permission to stop and hold a meeting on ministry land, outside the factory near Burghfield, Berks, making, warheads for Polaris submarine missiles. Autres temps, autres moeurs. Peggy Duff There were two reasons why it suddenly zoomed up in 1957.The first stimulus was the HBomb tests at Christmas Island in the Pacific. It was these that translated the committee formed in Hampstead in North London into a national campaign, and which brought into being a number of local committees around Britain which predated CND itself — in Oxford, in Reading, in Kings Lynn and a number of other places. Tests were a constant and very present reminder of the menace of nuclear weapons, affecting especially the health of children, and of babies yet unborn. Fallout seemed something uncanny, unseen and frightening. The Christmas Island tests, because they were British tests, at last roused opinion in Britain. The second reason was the failure of the Labour Party in the autumn of 1957 to pass, Peggy Duff was the first as expected, a resolution in favour of secretary of the Campaign unilateral abandonment of nuclear weapons for Nuclear Disarmament. -

Science Studies Probing the Dynamics of Scientific Knowledge

Sabine Maasen / Matthias Winterhager (eds.) Science Studies Probing the Dynamics of Scientific Knowledge 09.05.01 --- Projekt: transcript.maasen.winterhager / Dokument: FAX ID 012a286938514334|(S. 1 ) T00_01 schmutztitel.p 286938514390 09.05.01 --- Projekt: transcript.maasen.winterhager / Dokument: FAX ID 012a286938514334|(S. 2 ) vakat 002.p 286938514406 Sabine Maasen / Matthias Winterhager (eds.) Science Studies Probing the Dynamics of Scientific Knowledge 09.05.01 --- Projekt: transcript.maasen.winterhager / Dokument: FAX ID 012a286938514334|(S. 3 ) T00_03 innentitel.p 286938514414 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Die Deutsche Bibliothek – CIP-Einheitsaufnahme Science studies : probing the dynamics of scientific knowledge / Sabine Maasen / Matthias Winterhager (ed.). – Bielefeld : transcript, 2001 ISBN 3-933127-64-5 © 2001 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld Umschlaggestaltung: Kordula Röckenhaus, Bielefeld Satz: digitron GmbH, Bielefeld Druck: Digital Print, Witten ISBN 3-933127-64-5 09.05.01 --- Projekt: transcript.maasen.winterhager / Dokument: FAX ID 012a286938514334|(S. 4 ) T00_04 impressum.p 286938514422 To Peter Weingart and, of course, Henry Holorenshaw 09.05.01 --- Projekt: transcript.maasen.winterhager / Dokument: FAX ID 012a286938514334|(S. 5 ) T00_05 widmung.p 286938514430 09.05.01 --- Projekt: transcript.maasen.winterhager / Dokument: FAX ID 012a286938514334|(S. 6 ) vakat 006.p 286938514438 Contents Introduction 9 Science Studies. Probing the Dynamics of Scientific Knowledge Sabine Maasen and Matthias Winterhager 9 Eugenics – Looking at the Role of Science Anew 55 A Statistical Viewpoint on the Testing of Historical Hypotheses: The Case of Eugenics Diane B. Paul 57 Humanities – Inquiry Into the Growing Demand for Histories 71 Making Sense Wolfgang Prinz 73 Bibliometrics – Monitoring Emerging Fields 85 A Bibliometric Methodology for Exploring Interdisciplinary, ‘Unorthodox’ Fields of Science. -

The Rise and Fall of the Labour League of Youth

University of Huddersfield Repository Webb, Michelle The rise and fall of the Labour league of youth Original Citation Webb, Michelle (2007) The rise and fall of the Labour league of youth. Doctoral thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/761/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ THE RISE AND FALL OF THE LABOUR LEAGUE OF YOUTH Michelle Webb A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Huddersfield July 2007 The Rise and Fall of the Labour League of Youth Abstract This thesis charts the rise and fall of the Labour Party’s first and most enduring youth organisation, the Labour League of Youth. -

Constitution

Constitution 1. Name The name of the association is Momentum. 2. Administration The association shall be governed under this constitution by the members of the National Coordinating Group (“NCG”) as provided for under Rules 6 and 7 below. 3. Aims The association aims: ● To work for the election of a Labour government; ● To revitalise the Labour Party by building on the values, energy and enthusiasm of the Jeremy for Leader campaign so that Labour will become an effective, open, inclusive, participatory, democratic and member-led party of and in Government; ● To broaden support for a transformative, socialist programme; ● To unite people in their communities and workplaces to win victories on the issues that matter to them; ● To make politics more accessible to more people; ● To ensure a wide and diverse membership of Labour who are in and heard at every level of the party; ● To demonstrate how collective action and Labour values can transform our society for the better and improve the lives of ordinary people; and ● To achieve a society that is more democratic, fair and equal. 4. Commitments To achieve its aims the association will: ● Work towards the association’s affiliation to the Labour Party; ● Encourage those inspired by Jeremy Corbyn's leadership campaigns to join the Labour Party; ● Consult with its members using a variety of means including but not limited to surveys of members and local groups, referenda, and canvassing members at local, regional or national gatherings; ● Focus on issues and campaigns on which its members broadly -

Introduction

Notes Introduction 1. Michael Gove, 15 November 2010, Hansard Parliamentary Debates,column 634, www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm201011. 2. Ofsted made a statement to this effect on 11 July 2004 which was reported on by the BBC (http://news.bbc.co.uk/1/hi/education/3884087.stm) and The Telegraph (www.telegraph.co.uk/education/educationnews). 3. There is a growing literature on the Falklands War, most of which does not contextualise the conflict in terms of the British Empire despite the jingoistic use of imperial ideology during the conflict. 4. Bill Schwarz (2011) The White Man’s World, Memories of Empire, 1 (Oxford University Press), p. 6. 5. Avner Offer (1993) ‘The British Empire, 1870–1914: A Waste of Money?’, The Economic History Review 46, no. 2, 215–38. 6. Bernard Porter (2004) The Absent-Minded Imperialists: Empire, Society, and Culture in Britain (Oxford University Press); John M. MacKenzie (1984) Pro- paganda and Empire: The Manipulation of British Public Opinion, 1880–1960 (Manchester University Press). 7. Alan Sked (1987) Britain’s Decline: Problems and Perspectives (Oxford: Basil Blackwell). 8. Catherine Hall and Sonya Rose (2006) ‘Introduction: Being at Home with the Empire’, in Catherine Hall and Sonya O. Rose (eds), At Home with the Empire: Metropolitan Culture and the Imperial World (Cambridge University Press). 9. Bill Schwarz (1996) ‘ “The Only White Man in There”: The Re-Racialisation of England, 1956–1968’, Race and Class 38, no. 1, 65. 10. Stuart Ward (ed.) (2001) British Culture and the End of Empire,Studiesin Imperialism (Manchester University Press). 11. Stuart Ward (2001) ‘Introduction’, in idem (ed.), British Culture and the End of Empire (Manchester University Press), p. -

EU Thieves Fall out on Third World Markets

WORKERS OF ALL COUNTRIES, UNITE! No 1346 Week commencing 17 June 2005 Weekly paper of the New Communist Party of Britain 50p IRAQ US IMPERIALISTS READY TO TALK? by our Arab Affairs Correspondent And US defence min- anti-imperialist violence ister Donald Rumsfeld, one that has destroyed any le- IRAQI PARTISANS have broken the back of the of the chief war-mongers gitimacy the US occupation American offensive against the resistance inside in the Bush cabinet, has once claimed. And last the capital, Baghdad, while across the country confirmed that tentative week the resistance dem- talks between the puppet onstrated an authority of wave after wave of ambushes, raids and bombings their own when take a relentless toll on the forces of imperialism. regime and the partisans have taken place. Though Mujahideen units seized The Russian ambassa- American imperialist troops he refused to go into details, control of parts of south- dor held talks last week and wounded 13,000 more. he told the BBC that these western Baghdad for a with maverick Shia leader Last month 67 US soldiers contacts were broad-rang- time to show that they can Muqtada al Sadr. were killed in action, the ing and crucial to establish- take any area whenever The British expedition- fourth highest tally since ing stability. they want. The point was ary force in the south will the invasion in March 2003. rammed home with re- be cut within the next six “This insurgency is not a ploy? peated attacks on Baghdad months to free troops to going to be settled, the ter- International Airport and beef up the American pres- rorists and the terrorism in Whether it’s simply a the assassination of the ence in Afghanistan and a Iraq is not going to be ploy to split the resistance quisling Iraqi general in senior member of the Bush settled, through military or the beginning of the end charge of puppet troops in- administration has con- options or military opera- only time will tell. -

From the Cold War to the Kosovo War: Yugoslavia and the British Labour Party

Unkovski-Korica, V. (2019) From the Cold War to the Kosovo War: Yugoslavia and the British Labour Party. Revue d'Études Comparatives Est-Ouest, 2019/1(5), pp. 115-145. There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/189346/ Deposited on: 1 July 2019 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk 1 From the Cold War to the Kosovo War: Yugoslavia and the British Labour Party1 The protracted and violent collapse of Yugoslavia was one of the profound international crises following the end of the Cold War. The inability of the United Nations to stop the bloodshed, the retreat of Russian power alongside the failure of the European powers to reach a common approach, and the ultimate deployment of US-led NATO forces to settle the Bosnian War and later to conduct the Kosovo War exposed the unlikelihood of what George H.W. Bush had hailed as a ‘new world order’ based on collective security. The wars of succession in the former Yugoslavia in fact provided the spring-board for a different vision of global security under American hegemony, which would characterise in particular George W. Bush’s project to reshape global affairs in the new millennium (Rees, 2006, esp. pp. 34-35). It is unsurprising in this context that scholarly production relating to the collapse of Yugoslavia and its importance for international relations has been immense (for a recent short overview: Baker 2015). -

A Human Rights Approach to Policing Protest

House of Lords House of Commons Joint Committee on Human Rights Demonstrating respect for rights? A human rights approach to policing protest Seventh Report of Session 2008–09 Volume I Report, together with formal minutes and written evidence Ordered by the House of Commons to be printed 3 March 2009 Ordered by the House of Lords to be printed 3 March 2009 HL Paper 47-I HC 320-I Published on 23 March 2009 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £0.00 Joint Committee on Human Rights The Joint Committee on Human Rights is appointed by the House of Lords and the House of Commons to consider matters relating to human rights in the United Kingdom (but excluding consideration of individual cases); proposals for remedial orders, draft remedial orders and remedial orders. The Joint Committee has a maximum of six Members appointed by each House, of whom the quorum for any formal proceedings is two from each House. Current membership HOUSE OF LORDS HOUSE OF COMMONS Lord Bowness John Austin MP (Labour, Erith & Thamesmead) Lord Dubs Mr Andrew Dismore MP (Labour, Hendon) (Chairman) Lord Lester of Herne Hill Dr Evan Harris MP (Liberal Democrat, Oxford West & Lord Morris of Handsworth OJ Abingdon) The Earl of Onslow Mr Virendra Sharma MP (Labour, Ealing, Southall) Baroness Prashar Mr Richard Shepherd MP (Conservative, Aldridge-Brownhills) Mr Edward Timpson MP (Conservative, Crewe & Nantwitch) Powers The Committee has the power to require the submission of written evidence and documents, to examine witnesses, to meet at any time (except when Parliament is prorogued or dissolved), to adjourn from place to place, to appoint specialist advisers, and to make Reports to both Houses.