Book Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Romero: Person and His Charisma with the Pontiffs

260914: Julian Filochowski Romero: Person and His Charisma with the Pontiffs. It is my intuition that ‘the annunciation’ is just around the corner; that is an announcement from Rome - not from the Angel Gabriel, but from the Cardinal ‘Angel’ (Angelo) Amato, Head of the Congregation for the Causes of the Saints – an announcement that our beloved Servant of God, Oscar Romero, will be raised to the altars during 2015. Oremus! Archbishop Romero is not only the most famous Salvadoran of our times, but also the most loved and simultaneously the most hated. Nevertheless it seems entirely fitting to me to adapt the words from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, “he was the noblest Salvadoran of them all”. Indeed today he is recognised as such, repeatedly acclaimed by President Funes as the ‘spiritual guide of the nation’ - with monuments and memorials in almost every town and village in El Salvador. He has been described as a national treasure. As a holy prophet and martyr, Oscar Romero is, I would suggest, a precious diamond, who adds a special redemptive lustre to the universal Church of the 20th century. For over 30 years, however, Archbishop Romero’s detractors inside the Church have tried to paint a picture of him as a rather cheap fake diamond - naïve, vain, manipulated, doctrinally heterodox and politically extreme. (In truth they feared Romero’s canonisation might be interpreted as the canonisation of liberation theology.) And they are still not finished - even though their curial leader, the Colombian Cardinal Alfonso Lopez Trujillo, has now gone to that great dicastery in the sky, with God. -

The Last Confession by Roger Crane

THE LAST CONFESSION BY ROGER CRANE DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE INC. THE LAST CONFESSION Copyright © 2014, Roger Crane All Rights Reserved CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that performance of THE LAST CONFESSION is subject to payment of a royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan- American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights, including without limitation professional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical, electronic and digital reproduction, transmission and distribution, such as CD, DVD, the Internet, private and file-sharing networks, information storage and retrieval systems, photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved. Particular emphasis is placed upon the matter of readings, permission for which must be secured from the Author’s agent in writing. The English language stock and amateur stage performance rights in the United States, its territories, possessions and Canada for THE LAST CONFESSION are controlled exclusively by DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. No professional or nonprofessional performance of the Play may be given without obtaining in advance the written permission of DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., and paying the requisite fee. Inquiries concerning all other rights should be addressed to Alan Brodie Representation, Paddock Suite, The Courtyard, 55 Charterhouse Street, London EC1M 6HA, England. -

Archbishop with an Attitude : Oscar Romero's Sentir Con La Iglesia

Archbishop with an Attitude Oscar Romerds Sentir con la Iglesia Douglas Marcouiller, S.J. BX3701 S88x Studies in the spirituality of Jesuits. Issue: v.35:no.3(2003:May) Arrival Date: 05/22/2003 O'Neill Periodicals 35/3 • MAY 2003 THE SEMINAR ON JESUIT SPIRITUALITY The Seminar is composed of a number of Jesuits appointed from their provinces in the United States. It concerns itself with topics pertaining to the spiritual doctrine and practice of Jesuits, especially United States Jesuits, and communicates the results to the members of the provinces through its publication, STUDIES IN THE SPIRITUALITY OF JESUITS. This is done in the spirit of Vatican Li's recommendation that religious institutes recapture the original inspiration of their founders and adapt it to the circumstances of modern times. The Seminar welcomes reactions or comments in regard to the material that it publishes. The Seminar focuses its direct attention on the life and work of the Jesuits of the United States. The issues treated may be common also to Jesuits of other regions, to other priests, religious, and laity, to both men and women. Hence, the journal, while meant especially for American Jesuits, is not exclusively for them. Others who may find it helpful are cordially welcome to make use of it. CURRENT MEMBERS OF THE SEMINAR Robert L. Bireley, S.J., teaches history at Loyola University, Chicago, IL (2001). Richard A. Blake, S.J., is chairman of the Seminar and editor of STUDIES; he teaches film studies at Boston College, Chestnut Hill, MA (2002). Claudio M. Burgaleta, S.J., is executive director of Estudios Pastorales para la Nueva Evangelizacion, in Oceanside, NY (2002). -

Servant of God Fra' Andrew Bertie

SERVANT OF GOD FRA’ ANDREW BERTIE A BOOKLET_GENERIC.indd 1 02/07/2020 15:34 © BASMOM 2020 Email: [email protected] website: www.orderofmalta.org.uk Registered Charity No. 1103567 (England & Wales) Registered Charity No. SCO 040124 (Scotland) Company No. 05039938 B BOOKLET_GENERIC.indd 2 02/07/2020 15:34 CONTENTS Introduction ....................................................... 3 Election as 78th Grand Master ........................... 5 Works as Grand Master ...................................... 7 Spirituality ......................................................... 9 Early years ........................................................ 11 Works for the Order of Malta ........................... 11 Death of Fra’ Andrew Bertie ............................. 17 The path to sainthood ..................................... 19 Prayers of intercession ...................................... 23 1 BOOKLET_GENERIC.indd 1 02/07/2020 15:34 A current and a future Grand Master: Fra’ Andrew Bertie with Fra’Giacomo Dalla Torre del Tempio di Sanguinetto 2 BOOKLET_GENERIC.indd 2 02/07/2020 15:34 INTRODUCTION Fra’ Andrew Bertie, 78th Grand Master of the Sovereign Order of Malta, was a deeply respected and revered figure, by the 13,500 members of the Order worldwide, by the Church, and by all with whom he came into contact. His vocation, as a Professed Knight of the Order, was to care for the poor and the sick, and to demonstrate this inspiration through his deep Christian spirituality. He lived modestly, with humility and with intense faith. -

The Battalion • Impressions of Sunday’S Race Tuesday, August 8, 1978 News Dept

Inside Tuesday » A&M graduates guard Lady Bird Johnson — p. 3. » Manilow concert scheduled for this fall is canceled — p. 3. The Battalion • Impressions of Sunday’s race Tuesday, August 8, 1978 News Dept. 845-2611 - p. 8. College Station, Texas Business Dept. 845-2611 Pope’s successor to be named by large group of cardinals By ERNEST SAKLER Italian “papabili ’ — potential papal candidates — year-old Segri-born Felici is a polished and pungent United Press International include Cardinals Giovanni Benelli, Sergio Pignedoli, speaker who leans toward the conservative. He is dis VATICAN CITY — Pope Paul Vi’s successor, whose Sebastiano Baggio, Pericle Felici, Giovanni Colombo, trusted by church progressives. A cardinal since 1967, election will decide the future of the Roman Catholic Michele Pellegrino, Antonio Poma, Corrado Ursi and his lack of pastoral experience could hurt him in papal church and perhaps the allegiance of nearly 700 million Albino Luciani. balloting. faithful, probably will come from a group of fewer than Non-Italian cardinals, who were given long-shot Luciani: A theologian and philosopher, he is one of 20 cardinals, Vatican experts said Monday. chances for election, include American Cardinals John the newest cardinals, named in 1973. Born in Forno di Predicting the outcome of a papal election is always F. Dearden and John J. Wright, Leon Duval of Canale in 1912 he is vice president of the Italian difficult, but particularly so this time because the Col Algeria, Gabriel Garrone and Jean Villot of France, Bishops’ Conference. lege o* Cardinals is the largest in history. James Knox of Australia, Franz Koenig of Austria, Pellegrino: The retired archbishop of Turin is There will be 115 cardinals meeting in Maurice Roy of Canada, Johannes Willenbrands of Hol viewed by many traditionalists as too liberal. -

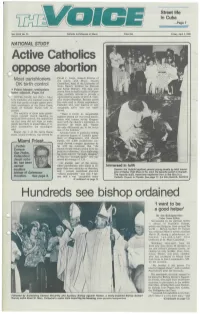

Active Catholics >E Abortion

Street life in Cuba ...Page 7 Vol. XXXII No. 33 Catholic Archdiocese of Miami Price 250 Friday, April 4, 1986 NATIONAL STUDY Active Catholics >e abortion David C. Leege, research director of Most parishioners the study, and Msgr. Joseph Gremillion, head of the University of OK birth control Notre Dame's Institute for Pastoral • Priests happier, seminarians and Social Ministry. The data were drawn from in-depth studies of 36 par- better adjusted, Pages 5-6 ishes, carefully selected to provide a NOTRE DAME, Ind. (NC) — Most representative sample of all U.S. Cath- U.S. Catholics who maintain some ties olics except Hispanics. Because parish with their parish strongly oppose abor- lists were used to obtain respondents, tion, sociologists of the Notre Dame Catholics who were inactive or only Study of Catholic Parish Life re- marginally active were not repre- ported. sented. The majority of those same parish- "There is simply no recognizable ioners rejected church teaching on segment among our (surveyed) parish- artificial birth control, but opposition ioners who express strong disagree- on that issue did not seem to make ment with the church's opposition to people less likely to attend Mass or re- abortion," the report said. "Rather ceive Communion the sociologists the only differences are in the strict- said. ness of the position." Report No. 7 of the Notre Dame Among a series of questions seeking study, issued in March, was written by to uncover degrees of Catholic agree- ment or disagreement with church stands, the 2,600 parishioners sur- — Miami Priest... veyed showed strongest agreement by ...Father far with the statement that "the Enrique church should remain strong in its op- position to abortion." On a scale rang- San Pedro, ing from one for "strongly disagree" Cuban-born to four for "strongly agree," they reg- Jesuit scho- istered an average of 3.35. -

Short Conclave Is Expected Two Italians Are Frontrunners

PRICE 25c AUGUST tl/OICE25, 1978 VOL. XX No. 25 Short conclave is expected Two Italians are frontrunners By JOHN MUTHIG VATICAN CITY-(NC)-A quick decision was ex- pected as 111 red-robed cardinals headed into conclave in the Vatican's Apostolic Palace to pick the 262nd successor of St. Peter and the spiritual leader of some 700 million Catholics. Observers predicted that the conclave would take four days or less of voting after its Aug. 25 opening. , THE LEADING candidates appeared to be Cardinal Sebastiano Baggio, 65, prefect of the powerful Vatican congregation which oversees the naming of bishops, and Cardinal Sergio Pignedoli, 68, a close friend of the late Pope Paul VI and president of the Vatican body which promotes dialogue with non-Christian religions. The vast pastoral, diplomatic and curial experience of the two men made them strong favorites in a conclave ex- pected to continue the 455-year-old tradition of an Italian pope. It remained possible, however, that the first conclave since the Second Vatican Council, the largest and most international conclave ever, would decide to give the world a non-Italian pontiff. Front-running non-Italian candidates included charismatic Cardinal Eduardo Pironio, 57, prefect of the Congregation for Religious, former head of the large Mar del Plata Diocese in Argentina and conciliatory general secretary of the Latin American Bishops' Council (CELAM). At the same time, some Vatican watchers were saying that cardinals seeking a pope who would share more power with local churches might decide to give their votes to Franciscan Cardinal Aloisio Lorscheider, president of both CELAM and the Brazilian Bishops' Conference. -

Pope Kulto Elevate

X 1? Courier-Journal — Friday, April 4, 1969 Pope KuLto Elevate coming a cardinal on April 28, has customarily are not made until after (Continued from Page 1) ing elected president of the National (ContinuedT from Page 1) the, cosmos, the goodness_ojE God t£ Conference of Catholic Bishops long been recognized as one of the the consistory at which the new cardi ~ oitr fathers, how He liberated us , In his year as Archbishop of New -HNCCB) and the United States Catho most eloquent, versatile and experi nals are elevated. But unofficial priests and people to sing praise to York, Cardinal-designate Cooke, 48, 1 from slavery, of both the flesh and! lic Conference (NSCC), is best enced. Catholic churchmen in the x sounieb_Jia3reJsrw)ken„cif_two possible the Risen One:--~i , the youngest of the 10 U.S. cardi known in Detroit as a bishop deep- United States. appointments; The Secretariat for 'the spirit, bur visions of the future. nals, has already made an impres ly concerned with the prohreniria*"' Promoting Christian Unity, whose Our story mtunts as we begin four and His sombre warning of the price .- sive record in the fields of social the people of his archdiocese, He was singled out for special men first president, Augustine Cardinal lessons and four songs from Sacred\ "of our infidelity to His plan. action and ecumenical activity. tion by Archbishop Luigi Raimondi, Bea, died In November, and the Vati Scripture, telling of the origins~7sr Then we call out IhlT names of He is a tall, (6 foot 1) personable Apostolic Delegate to the U.S., in a can Secretariat of State, whose head, those present who-have-gomr before - The successor to the Me„ J&anck . -

Chiesa Viva 506 LA

YEAR XLIX 529 SEPTEMBER 2019 «Truth will make you free» (Jo. 8, 32) MENSILE DI FORMAZIONE E CULTURA ChiesavivaFONDATORE e Direttore (1971-2012): sac. dott. Luigi Villa Direttore responsabile: dott. Franco Adessa Direzione - Redazione - Amministrazione: Operaie di Maria Immacolata e Editrice Civiltà Via G. Galilei, 121 25123 Brescia Tel. e fax (030) 3700003 www.chiesaviva.com Autor. Trib. Brescia n. 58/1990 - 16-11-1990 Fotocomposizione in proprio Stampa: Com & Print (BS) contiene I. R. e-mail: [email protected] Poste Italiane S.p.a. Spedizione in Abbonamento Postale D.L. 353/2003(conv. L. 27/02/2004 n° 46) art. 1, comma 2, DCB Brescia. Abbonamento annuo: ordinario Euro 40, sostenitore Euro 65 - una copia Euro 3,5 arretrata Euro 4 (inviare francobolli). Per l’estero: Euro 65 + sovrattassa postale. Le richieste devono essere inviate a: Operaie di Maria Immacolata e Editrice Civiltà Via G. Galilei, 121 25123 Brescia, C.C.P. n. 11193257 I manoscritti, anche se non pubblicati, non vengono restituiti Ogni Autore scrive sotto la sua personale responsabilità «THIS IS HOW I, AS A YOUNG PRIEST HAVE (NOT) BEEN TRAINED» by a young priest young priest wrote an ar- sonic Temple?” began on Febru- ticle, then sent to Carlo ary 20, 2006. This special edition Maria Valli, with these demonstrates the Masonic-Satanic Awords of introduction: «I must ad- nature of this new church and the dress a subject that is hardly ever existence of horrible offenses talked about, but this subject is against Jesus Christ and the Holy quite important because it is about Trinity. -

Diary of a Pontificate

Diary of a Pontificate From Conclave to Funeral 25 August - 4 October 1978 25 August - At 19.00 the announcement of the extra omnes heralds in the conclave, it marks the first such event since the Second Vatican Council. At the time the Patriarch of Venice, Cardinal Albino Luciani, in his last letter to his sister Antonia writes: «Ahead of me lies no danger». 26 August - By the fourth ballot the quorum is reached with an almost unanimous consent. Cardinal Albino Luciani assents to the election and takes the name of John Paul. At 19.20 the proto-deacon Cardinal Pericle Felici announces the Habemus Papam. At 19.30 John Paul I appears at the central balcony of St. Peter's Basilica to impart his Apostolic blessing. The cardinals prolong their stay in the conclave area until the following morning. 27 August - At 9.30 Eucharistic concelebration together with all the cardinals: those to elect him and those over eighty, excluded from the conclave because of their age. His first Urbi et Orbi radio message outlines the six point programme, or ‘vogliamo’, of his pontificate. At his first Angelus appearance he says: «I hope you will support me with your prayers». Unexpectedly he renounces the traditional plural maiestatis, or royal we. Takes possession of his private apartment on the third floor of the Apostolic Palace accompanied by his secretary, Don Diego Lorenzo. 28 August - Names Cardinal Jean Villot as Secretary of State and reconfirms all other official curial posts. 29 August - Names Monsignor Giuseppe Bosa as apostolic administrator of Venice and sends a message to Venetians. -

The Tradition

14-15 Tablet 25 Apr 09 Mic 22/4/09 3:37 pm Page 4 ROBERT MICKENS Return to the Tradition More than 30 years ago when Pope Paul VI instructed Catholics Portraits of Pope Benedict XVI and Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre, founder that they must use the new rite of Mass, it dismayed of the Society of St Pius X, in St Michael traditionalists. But a group of cardinals over many years strove to the Archangel Chapel in Farmingville, New York. Photo: CNS/ ensure that the vernacular would not supplant the old Mass Gregory A. Shemitz n the summer of 1980 the late Pope John scient. “According to the bishops, the spirit confidently, ‘hopes to intervene with the Paul II authorised the then Sacred that has been created in these groups leads Pope to find a solution’,” Zizola wrote. Congregation for the Sacraments and one to think that an eventual concession to In an address in Long Island, New York, Divine Worship to conduct a consulta- use the Tridentine Rite would mark the begin- in November 1983, Archbishop Lefebvre Ition with the heads of all Latin rite dioceses ning … of an attitude of defiance towards all named Cardinal Ratzinger among those he around the world. The Congregation, at that that was established by the Second Vatican considered to be his most sympathetic allies time headed by Australian Cardinal James R. Council.” in the Vatican. The other two were Cardinal Knox, put two principal questions to the bish- The report on the episcopal consultation Silvio Oddi, Prefect of the Congregation for the ops. -

Libro 50 Años

185 QUINTA PARTE LA CAL A PARTIR DE LA REFORMA DE PABLO VI DE 1969 A 1988 186 187 La decisión de Pablo VI de inserir la Pontificia Comisión para América Latina en la Sagrada Congregación para los Obispos marca un nuevo momento en la historia de este organismo de la Curia Romana. El ambiente de renovación y de aggiornamento que inspiró el Concilio Vaticano II se dejó sentir en la Curia Romana en la reforma que Pablo VI sancionó con la publicación de la Constitución Apostólica Regimini Ecclesiae Universae, lo que provocó la creación de nuevos organismos, la desaparición de algunos y la reestructuración de otros. Con respecto a la CAL el Santo Padre dispuso que asumiera una nueva configuración en correspondencia con las cambiantes circunstancias de la Iglesia y de la sociedad en América Latina y en Europa. El Episcopado latinoamericano era cada vez más organizado y tomaba mayor conciencia de su misión y de su protagonismo en la renovación del catolicismo en el Continente, lo que exigía una presencia más activa en los organismos centrales de la Santa Sede que se ocupaban de la Iglesia en Latinoamérica. Así, pues, la nueva etapa de la historia de la CAL revela una reestructuración de la Comisión misma y de su Consejo General con mayor presencia del Episcopado de América Latina. Se evidencia, igualmente, una relevante presencia del CELAM y de los Obispos latinoamericanos en el estudio y búsqueda de soluciones de los problemas pastorales y doctrinales que se presentaban a la acción evangelizadora de la Iglesia. Es, en definitiva, un período en el cual los esfuerzos de la Iglesia en favor de la renovación católica del Continente comienzan a dar sus frutos.