Archbishop with an Attitude : Oscar Romero's Sentir Con La Iglesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018

Lesser Feasts and Fasts 2018 Conforming to General Convention 2018 1 Preface Christians have since ancient times honored men and women whose lives represent heroic commitment to Christ and who have borne witness to their faith even at the cost of their lives. Such witnesses, by the grace of God, live in every age. The criteria used in the selection of those to be commemorated in the Episcopal Church are set out below and represent a growing consensus among provinces of the Anglican Communion also engaged in enriching their calendars. What we celebrate in the lives of the saints is the presence of Christ expressing itself in and through particular lives lived in the midst of specific historical circumstances. In the saints we are not dealing primarily with absolutes of perfection but human lives, in all their diversity, open to the motions of the Holy Spirit. Many a holy life, when carefully examined, will reveal flaws or the bias of a particular moment in history or ecclesial perspective. It should encourage us to realize that the saints, like us, are first and foremost redeemed sinners in whom the risen Christ’s words to St. Paul come to fulfillment, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” The “lesser feasts” provide opportunities for optional observance. They are not intended to replace the fundamental celebration of Sunday and major Holy Days. As the Standing Liturgical Commission and the General Convention add or delete names from the calendar, successive editions of this volume will be published, each edition bearing in the title the date of the General Convention to which it is a response. -

We Are Pleased and Honored to Welcome You to St. Francis of Assisi Parish

We are pleased and honored Military Service Honor Roll To welcome you to LCPL Alex Bielawa, U.S. Marines Lt. Colonel William J. Girard, U.S. Army St. Francis of Assisi Parish Sgt. Derek Keegan, U.S. Army 67 West Town Street, Lebanon, CT 06249 Major Michael A. Goba, U.S. Army JAG Telephone: 860.642.6711 Fax: 860.642.4032 E-5 Francis Orcutt, U.S. Army HMC Heather S. Gardipee, U.S. Navy Rev. Mark Masnicki, Pastor Pvt. Zachary Berquist, U.S. Army Rev. Benjamin Soosaimanickam, Parochial Vicar Pvt. First Class Jacob Grzanowicz Deacon Michael Puscas Sgt. Justin A. VonEdwins, U.S. Army Sgt. Robert Massicotte U.S. Army 1st Lt. Miles N. Snelgrove USMC 2 nd Batt. 6 th Marines Airman Emerson Flannery, U.S. Navy Saturday June 25, 2016 Blessed Virgin Mary Prayer for our Men and Women in Military Service 4:00 PM Confessions 5:00 PM For the Souls in Purgatory O Prince of Peace, we humbly ask Your protection for all our Sunday, June 26, 2016 13th Sunday in Ordinary Time men and women in military service. Give them unflinching 8:00 AM People of the parish living & deceased courage to defend with honor, dignity, and devotion the rights of 10:30 AM Bert & Rachel Bosse 55 th wedding anniversary all who are imperiled by injustice and evil. Guard our churches, Monday June 27, 2016 St. Cyril of Alexandria, bishop, doctor our homes, our schools, our hospitals, our factories, our of the Church buildings and all those within from harm and peril. Protect our NO MASS land and its peoples from enemies within and without. -

General Curia Excerpts from a Message of Fr

Vol. 74 No. 4 - 5 April - May 2020 General Curia Excerpts from a message of Fr. General Father Rutilio Grande and companions The current experience of COVID -19 is showing us many things about ourselves and our world. I want to focus on how it is lighting up aspects of our path to God First of all, it is showing us that we are one humanity. It is showing us how overcoming a crisis is possible. It is possible when we begin looking after the Common Good. Pope Francis has authorized the Congregation for the Causes of the Saints to promulgate the It is showing us that there is no difference in decree on the martyrdom of the Jesuit priest age, race, religion or social status within our Rutilio Grande and his two lay companions, one humanity. Manuel Solórzano and Nelson Rutilio Lemus. It is showing us that we want to walk together. Fr. Rutilio courageously defended the We are all concerned, we help each other to defenseless. He suffered public persecution and overcome fears and anxieties. was eventually assassinated on 12 March 1977, It is showing us the competence and generosity alongside the catechist, Manuel Solórzano - of those who are in the front line, caring for aged 72 years, and the young Nelson Rutilio those affected, seeking solutions or making Lemus - aged 16 years. We shall soon witness difficult decisions for the good of all. the beatification of these three martyrs. It is showing us the power of faith, the strong bonds that unite believers, the love of Jesus Christ that impels us, reconciles us and unites Notice: In view of the current situation, Fr. -

Great Cloud of Witnesses.Indd

A Great Cloud of Witnesses i ii A Great Cloud of Witnesses A Calendar of Commemorations iii Copyright © 2016 by The Domestic and Foreign Missionary Society of The Protestant Episcopal Church in the United States of America Portions of this book may be reproduced by a congregation for its own use. Commercial or large-scale reproduction for sale of any portion of this book or of the book as a whole, without the written permission of Church Publishing Incorporated, is prohibited. Cover design and typesetting by Linda Brooks ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-962-3 (binder) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-966-1 (pbk.) ISBN-13: 978-0-89869-963-0 (ebook) Church Publishing, Incorporated. 19 East 34th Street New York, New York 10016 www.churchpublishing.org iv Contents Introduction vii On Commemorations and the Book of Common Prayer viii On the Making of Saints x How to Use These Materials xiii Commemorations Calendar of Commemorations Commemorations Appendix a1 Commons of Saints and Propers for Various Occasions a5 Commons of Saints a7 Various Occasions from the Book of Common Prayer a37 New Propers for Various Occasions a63 Guidelines for Continuing Alteration of the Calendar a71 Criteria for Additions to A Great Cloud of Witnesses a73 Procedures for Local Calendars and Memorials a75 Procedures for Churchwide Recognition a76 Procedures to Remove Commemorations a77 v vi Introduction This volume, A Great Cloud of Witnesses, is a further step in the development of liturgical commemorations within the life of The Episcopal Church. These developments fall under three categories. First, this volume presents a wide array of possible commemorations for individuals and congregations to observe. -

Romero's Legacy 2

ROMERO’S LEGACY 2 Faith in the City: Poverty, Politics, and Peacebuilding Foreword by Robert T. McDermott Edited by Pilar Hogan Closkey Kevin Moran John P. Hogan The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy Copyright © 2014 by The Council for Research in Values and Philosophy Box 261 Cardinal Station Washington, D.C. 20064 All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Romero’s legacy 2. Faith in the City: Poverty, Politics, and Peacebuilding / edited by Pilar Hogan Closkey, Kevin Moran and John P. Hogan. p. cm. -- Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Faith. 2. Justice and Politics. 3. Religion—Christianity. I. Hogan, John P. II. Hogan Closky, Pilar. III. Moran, Kevin. BT83.57.R66 2007 2007014078 261.8-dc22 CIP ISBN 978-1-56518-2981 (pbk.) TABLE OF CONTENT Foreword: A Vision for an Urban Parish v Robert T. McDermott Preface xiii Pilar Hogan Closkey, Kevin Moran and John P. Hogan Introduction: Faith in the City: Joy and Belief in the 1 Midst of Struggle Pilar Hogan Closkey and Kevin Moran Chapter 1 The Challenge of God’s Call to Live Justly 13 Tony Campolo Chapter 2 The Hidden Face of Racism: Catholics Should 27 Stand Firm on Affirmative Action Bryan N. Massingale Chapter 3 Images of Justice: Present among Us: 37 Remembering Monsignor Carolyn Forché Chapter 4 Politics and the Pews: Your Faith, 57 Your Vote and The 2012 Election Stephen F. Schneck Chapter 5 Justice or Just Us: World Changing 63 Expressions of Faith Jack Jezreel Chapter 6 Make Us Instruments of Peace: 77 Peacebuilding in the 21st Century Maryann Cusimano Love Appendices A. -

Archbishop Romero's Homilies A

ARCHBISHOP ROMERO’S HOMILIES A THEOLOGICAL AND PASTORAL ANALYSIS THOMAS GREENAN This was translated from the original Spanish by the Archbishop Romero Trust. It is available to download from www.romerotrust.org.uk. Contents INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................. 10 CHRONOLOGY OF THE LIFE OF OSCAR ROMERO .................................................................... 13 CHAPTER ONE - OSCAR ROMERO, BELIEVER IN GOD ................................................................ 14 1.1 The person of Oscar Romero ........................................................................................................... 14 1.1.1 The childhood of Oscar Romero ................................................................................................ 14 1.1.2 Seminarian and priest .................................................................................................................... 14 1.1.3 The sheep and the wolves are just the same .............................................................................. 14 1.1.4 Secretary of the El Salvador Bishops’ Conference (CEDES) ................................................. 15 1.1.5 Editor of the weekly bulletin Orientación .................................................................................. 15 1.1.6 Auxiliary Bishop of San Salvador ................................................................................................ 15 1.1.7 -

Romero: Person and His Charisma with the Pontiffs

260914: Julian Filochowski Romero: Person and His Charisma with the Pontiffs. It is my intuition that ‘the annunciation’ is just around the corner; that is an announcement from Rome - not from the Angel Gabriel, but from the Cardinal ‘Angel’ (Angelo) Amato, Head of the Congregation for the Causes of the Saints – an announcement that our beloved Servant of God, Oscar Romero, will be raised to the altars during 2015. Oremus! Archbishop Romero is not only the most famous Salvadoran of our times, but also the most loved and simultaneously the most hated. Nevertheless it seems entirely fitting to me to adapt the words from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, “he was the noblest Salvadoran of them all”. Indeed today he is recognised as such, repeatedly acclaimed by President Funes as the ‘spiritual guide of the nation’ - with monuments and memorials in almost every town and village in El Salvador. He has been described as a national treasure. As a holy prophet and martyr, Oscar Romero is, I would suggest, a precious diamond, who adds a special redemptive lustre to the universal Church of the 20th century. For over 30 years, however, Archbishop Romero’s detractors inside the Church have tried to paint a picture of him as a rather cheap fake diamond - naïve, vain, manipulated, doctrinally heterodox and politically extreme. (In truth they feared Romero’s canonisation might be interpreted as the canonisation of liberation theology.) And they are still not finished - even though their curial leader, the Colombian Cardinal Alfonso Lopez Trujillo, has now gone to that great dicastery in the sky, with God. -

St Maurice at Resurrection Catholic Church 441 NE 2Nd St, Dania Beach, FL 33004 954-961-7777 FAX 954-961-4358 October 7, 2018 We Have a Seat Saved for You

St Maurice at Resurrection Catholic Church 441 NE 2nd St, Dania Beach, FL 33004 954-961-7777 FAX 954-961-4358 October 7, 2018 We Have A Seat Saved For You PARISH OFFICE DISASTROUS Monday–Friday: 9:00am–5:00pm CONFESSION "He Who has brought Saturday: 3:00pm (Chapel) disaster upon you will, in saving you, bring you BAPTISM back enduring joy." — The baptism of children of registered Baruch 4:29 parishioners is celebrated on the last Sunday of each month. Most people have suffered disasters in their lives. Some ANOINTING OF THE SICK of these have been caused This sacrament is celebrated once a by our own sins. If we would year during weekend Masses and is seek the Lord ten times more zealously than we strayed from Him, He available at other times on request. would save us from disaster and bring us back a joy that this time will last PASTORAL CARE OF THE SICK (Bar 4:28). Our Parish Care Givers bring the The Lord turns all things, even disasters, to the good for those who love Eucharist to those who are sick in Him (Rm 8:28). If we repent and seek the Lord, we will understand that the hospitals, nursing homes or in their sufferings of the present are "nothing compared with the glory to be own residences. revealed in us" (Rm 8:18). We may go forth weeping, but we'll come back rejoicing (Ps 126:6). The Lord will change our mourning into dancing, our MARRIAGE sackcloth into robes of gladness (Ps 30:12), and our darkness into dawn (Ps Couples contemplating this 30:6). -

The Last Confession by Roger Crane

THE LAST CONFESSION BY ROGER CRANE DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE INC. THE LAST CONFESSION Copyright © 2014, Roger Crane All Rights Reserved CAUTION: Professionals and amateurs are hereby warned that performance of THE LAST CONFESSION is subject to payment of a royalty. It is fully protected under the copyright laws of the United States of America, and of all countries covered by the International Copyright Union (including the Dominion of Canada and the rest of the British Commonwealth), and of all countries covered by the Pan- American Copyright Convention, the Universal Copyright Convention, the Berne Convention, and of all countries with which the United States has reciprocal copyright relations. All rights, including without limitation professional/amateur stage rights, motion picture, recitation, lecturing, public reading, radio broadcasting, television, video or sound recording, all other forms of mechanical, electronic and digital reproduction, transmission and distribution, such as CD, DVD, the Internet, private and file-sharing networks, information storage and retrieval systems, photocopying, and the rights of translation into foreign languages are strictly reserved. Particular emphasis is placed upon the matter of readings, permission for which must be secured from the Author’s agent in writing. The English language stock and amateur stage performance rights in the United States, its territories, possessions and Canada for THE LAST CONFESSION are controlled exclusively by DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., 440 Park Avenue South, New York, NY 10016. No professional or nonprofessional performance of the Play may be given without obtaining in advance the written permission of DRAMATISTS PLAY SERVICE, INC., and paying the requisite fee. Inquiries concerning all other rights should be addressed to Alan Brodie Representation, Paddock Suite, The Courtyard, 55 Charterhouse Street, London EC1M 6HA, England. -

Promotio Iustitiae No

Nº 117, 2015/1 Promotio Iustitiae Martyrs for justice From Latin America Juan Hernández Pico, SJ Aloir Pacini, SJ From Africa David Harold-Barry, SJ Jean Baptiste Ganza, SJ From South Asia William Robins, SJ M.K. Jose, SJ From Asia Pacific Juzito Rebelo, SJ Social Justice and Ecology Secretariat Social Justice and Ecology Secretariat Society of Jesus Editor: Patxi Álvarez sj Publishing Coordinator: Concetta Negri Promotio Iustitiae is published by the Social Justice Secretariat at the General Curia of the Society of Jesus (Rome) in English, French, Italian and Spanish. Promotio Iustitiae is available electronically on the World Wide Web at the following address: www.sjweb.info/sjs If you are struck by an idea in this issue, your brief comment is very welcome. To send a letter to Promotio Iustitiae for inclusion in a future issue, please write to the fax or email address shown on the back cover. The re-printing of the document is encouraged; please cite Promotio Iustitiae as the source, along with the address, and send a copy of the re-print to the Editor. 2 Social Justice and Ecology Secretariat Contents Editorial .................................................................................. 4 Patxi Álvarez, SJ The legacy of the martyrs of El Salvador ..................................... 6 Juan Hernández Pico, SJ With martyrdom is reborn the hope of the indigenous peoples of Mato Grosso .......................................................................... 10 Aloir Pacini, SJ The seven Jesuit martyrs of Zimbabwe...................................... 14 David Harold-Barry, SJ Three grains planted in the Rwandan soil .................................. 18 Jean Baptiste Ganza, SJ A Haven for the Homeless: Fr. Thomas E. Gafney, SJ .................. 21 William Robins, SJ Fr. -

Padre Rutilio Grande. Profeta Y Mártir De América Latina

Nº 92 PADREPADRE RUTILIORUTILIO GRANDE.GRANDE. PROFETAPROFETA YY MÁRTIRMÁRTIR DEDE AMÉRICAAMÉRICA LATINA.LATINA. 2 INTRODUCCIÓN A 40 AÑOS INTRODUCCIÓN El 12 de marzo de 1977 en Aguilares, en el Salvador son acribillados a ba- lazos por los Escuadrones de la Muerte, Rutilio Grande, sacerdote jesuita de 49 años, y sus compañeros Nelson R. Lemus, de 16 años, y Manuel Solorzano, de 72 años. Es un momento en Centroamérica en el que están resurgiendo los movi- mientos sociales, en que está queriendo nacer un nuevo modelo de sistema de orientación socialista y cuando se están llevando a cabo procesos de luchas po- pulares, con la participación de muchos sectores de la población, en los que tam- bién se integran las Comunidades Eclesiales de Base (influenciadas éstas por la teología de la liberación). Rutilio, como salvadoreño, es consciente de las necesidades de su pueblo y se suma al proceso. Trabaja desde su parroquia en la concientización y también en la formación de líderes y de delegados de la palabra, dentro de su comunidad. Desde ahí denuncia las expulsiones, persecución y el silenciamiento de otros sa- cerdotes salvadoreños por parte de su gobierno. “Queridos hermanos y amigos, me doy perfecta cuenta que muy pronto la Biblia y el Evangelio no podrán cruzar las fronteras. Sólo nos llegarán las cubiertas, ya que todas las páginas son subversivas—contra el pecado, se entiende. De manera que si Jesús cruza la frontera cerca de Chalatenango, no lo dejarán entrar. Le acusarían al Hombre-Dios... de agitador, de forastero judío, que confunde al pueblo con ideas exóticas y foráneas, ideas contra la democracia, esto es, contra las minorías. -

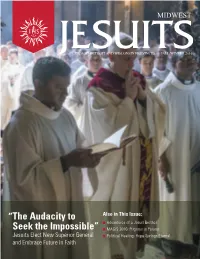

The Audacity to Seek the Impossible” “

MIDWEST CHICAGO-DETROIT AND WISCONSIN PROVINCES FALL/WINTER 2016 “The Audacity to Also in This Issue: n Adventures of a Jesuit Brother Seek the Impossible” n MAGIS 2016: Pilgrims in Poland Jesuits Elect New Superior General n Political Healing: Hope Springs Eternal and Embrace Future in Faith Dear Friends, What an extraordinary time it is to be part of the Jesuit mission! This October, we traveled to Rome with Jesuits from all over the world for the Society of Jesus’ 36th General Congregation (GC36). This historic meeting was the 36th time the global Society has come together since the first General Congregation in 1558, nearly two years after St. Ignatius died. General Congregations are always summoned upon the death or resignation of the Jesuits’ Superior General, and this year we came together to elect a Jesuit to succeed Fr. Adolfo Nicolás, SJ, who has faithfully served as Superior General since 2008. After prayerful consideration, we elected Fr. Arturo Sosa Abascal, SJ, a Jesuit priest from Venezuela. Father Sosa is warm, friendly, and down-to-earth, with a great sense of humor that puts people at ease. He has offered his many gifts to intellectual, educational, and social apostolates at all levels in service to the Gospel and the universal Church. One of his most impressive achievements came during his time as rector of la Universidad Católica del Táchira, where he helped the student body grow from 4,000 to 8,000 students and gave the university a strong social orientation to study border issues in Venezuela. The Jesuits in Venezuela have deep love and respect for Fr.