The Forgotten Army

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Masteroppgave I Kulturmøte

Masteroppgave i Kulturmøte Oppgavetittel: «Russenschwein!» Okkupasjonshistorie fra Solør med fokus på russiske tvangsarbeidere årene 1943-1945 ved Haslemoen leir – møte mellom lokalbefolkning, krigsfanger og Herrefolket. Studiepoeng: 60 Forfatternavn.: Elin Gundersen Mnd/År.: Mai 2017 Side 1 av 100 Abstract This thesis is looking into the local history in Solør during the Second World War, particularly russian prisoners of war. It will also briefly look in to how the story from Solør has been told for later generations in books and colloquially, and if the national and the local history is the story of the victor. There were also a relatively high share members of Nasjonal Samling, the Norwegian Nationalist Party, in the Solør area both before and during the Second World War. People in Solør, as many other places, had people on both sides that worked for or against the Government and people who just tried to live their lives as normal as they could. It’s the meeting between the different parts during the war and the first period in peacetime this thesis is also trying to look into. There were several million Soviet prisoners of war taken after Germany invaded The Soviet Union (USSR) June 22. 1941, this was called “Operation Barbarossa”. The nazis needed a lot of workers and forced their prisoners into labour. In Norway they had around 500 hundred small and bigger camps, Stalags, where forced working slaves were used for different things. Mostly in the infrastructure like roads, airports and railways. They usually didn’t get enough food, they were undernurished, and they often got sick. -

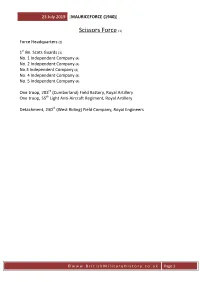

Scissors Force (1940)

23 July 2019 [MAURICEFORCE (1940)] Scissors Force (1) Force Headquarters (2) st 1 Bn. Scots Guards (3) No. 1 Independent Company (4) No. 2 Independent Company (4) No.3 Independent Company (4) No. 4 Independent Company (4) No. 5 Independent Company (4) One troop, 203rd (Cumberland) Field Battery, Royal Artillery One troop, 55th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment, Royal Artillery Detachment, 230th (West Riding) Field Company, Royal Engineers ©www.BritishMilitaryHistory.co.uk Page 1 23 July 2019 [MAURICEFORCE (1940)] NOTES: 1. Scissors Force was formed in early May 1940 under the command of Colonel Colin McVean GUBBINS. The role of this force was to form a base in the Bodo, Mo and Mosjoen area to the south of Narvik and to block and delay the German advance from the south. 2. The Force Headquarters was formed from the staff of the 61st Infantry Division on 15 April 1940. 3. The 1st Bn. Scots Guards was part of the 24th Infantry Brigade (Guards) which was sent to assist in blocking the road at Mo. 4. These companies were formed with volunteers from the Territorial Army divisions then stationed in the United Kingdom. They were: Ø No. 1 Independent Company – Formed by the 52nd (Lowland) Division; Ø No. 2 Independent Company – Formed by the 53rd (Welsh) Division; Ø No. 3 Independent Company – Formed by the 54th (East Anglian) Division; Ø No. 4 Independent Company – Formed by the 55th (West Lancashire) Division; Ø No. 5 Independent Company – Formed by the 56th (London) Division; Each company comprised five officers and about two-hundred and seventy men organised into three platoons, each consisting of three sections. -

Masteroppgave I Historie for Ingrid Lastein Hansen

Arbeiderpartiet og krisepolitikken i mellomkrigsårene En analyse av hovedlinjene i Arbeiderpartiets krisepolitiske syn, med utgangspunkt i Nygaardsvold-regjeringens krisepolitikk i perioden 1935-1938 Ingrid Lastein Hansen Masteroppgave i historie Høst 2010 Institutt for arkeologi, konservering og historie (IAKH) Universitetet i Oslo (UiO) Forord Denne oppgaven har blitt til gjennom en lang og krevende prosess. Først og fremst vil jeg takke veileder Einar Lie for gode faglige innspill, tilgjengelighet og ikke minst tålmodighet. En takk går også til familie og venner for oppmuntrende ord underveis. Arkivpersonalet på Riksarkivet fortjener en takk for informativ veiledning i arkivet. Til slutt vil jeg takke Odin for lange fine turer og et entusiastisk nærvær. Kragerø, 12. november, 2010, Ingrid Lastein Hansen 1 Innholdsfortegnelse Kapittel 1. Innledning .............................................................................................................. 4 1.1 Tema og problemstilling .................................................................................................. 4 1.2 Fremgangsmåte og begrepsavklaring............................................................................... 5 1.3 Tidligere fremstillinger .................................................................................................... 6 1.4 Kilder................................................................................................................................ 8 1.5 Disposisjon.................................................................................................................... -

The Rise and Fall of the Oslo School

Nordic Journal of Political Economy Volume 33 2007 Article 1 The Rise and Fall of the Oslo School ‡ Ib E. Eriksen* Tore Jørgen Hanisch † Arild Sæther * University of Agder, Faculty of Economics and Social Sciences, Kristiansand, Norway ‡ University of Agder, Faculty of Economics and Social Sciences, Kristiansand, Norway † University of Agder, Faculty of Economics and Social Sciences, Kristiansand, Norway This article can be dowloaded from: http://www.nopecjournal.org/NOPEC_2007_a01.pdf Other articles from the Nordic Journal of Political Economy can be found at: http://www.nopecjournal.org The Rise and Fall of the Oslo School 1 Ib E. Eriksen, Tore Jørgen Hanisch1, Arild Sæther The Rise and Fall of the Oslo School2 Abstract In 1931 Ragnar Frisch became professor at the University of Oslo. By way of his research, a new study programme and new staff he created the ”Oslo School”, characterised by mathematical modelling, econometrics, economic planning and scepticism towards the market economy. Consequently, detailed state economic planning and governance dominated Norwegian economic policy for three decades after WWII. In the 1970s the School’s dominance came to an end when the belief in competitive markets gained a foothold and the economy had poor performance. As a result a decentralized market economy was reintroduced. However, mathematical modelling and econometrics remain in the core of most economic programmes. JEL classification: B23, B29,B31, B59, O21, P41, P51 1. Introduction The main purpose of this presentation is to tell the story of how Ragnar Frisch founded the so-called Oslo School in economics, and secondly, to outline the main features of this School and investigate its major influence on the Norwegian post-war economy. -

Obituaries: Halvdan Koht and Lars Ahnebrink

Obituaries: Halvdan Koht and Lars Ahnebrink Halvdan Koht died in 1965, at the and again as a scholar, and as Nor- age of ninetytwo. In his rich life, wegian Minister of Foreign AfTairs, covering many hields of activity natio- establishing wide contacts with Ame- nal and international, the United rican intellectual life. He spent the States was one of the main formative war years of exile 1941-45 in the powcrs. As a young graduate in thc States, and uscd thcm on writing, 1890s hc went to the University of among others, his book on The Ameri- Leipzig, and studied with two of the can S~iritin Europe, the first attempt pioneers of modern American research to outline the impact of America on in Germany, the historians Erich this side of the Atlantic. hlarcks and Karl Lamprecht. He spent Halvdan Koht did not only know the year 1908-09 in America, - one America: lie loved it. His sober judg- of thc first Scandinavians to go therc mcnt of the less attractive sidcs of for scholarly studies of American civi- American dcvelopmcnt was ncver able lization. Upon his return, as professor to shake his faith in the youthful of History at thc University of Oslo, vigor and powcr of resilience in Ame- he made US ltistory an obligatory rican society. By his death America part of the curriculum, at a time whcn lost one of its staunchest friends in such requirements wcrc far from usual Europe, and (the study of America in in Europe. And in tcaching and the Scandinavian North one of its scholarship lie inaugurated in Norway Founding Fathers. -

“Norway Is a Peace Nation”

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NORA - Norwegian Open Research Archives “Norway is a Peace Nation” Discursive Preconditions for the Norwegian Peace Engagement Policy Øystein Haga Skånland M.A.Thesis, Peace and Conflict Studies Faculty of Social Science UNIVERSITY OF OSLO 20th June, 2008 ii Acknowledgements First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisor Halvard Leira for his insightful feedback, suggestions, and encouraging comments. Without him keeping me on track and gently prodding me in the right direction, carrying out the analysis would undoubtedly have been an overwhelming task. I am also grateful to Iver B. Neumann, who has read through and given valuable comments on a draft in the finishing stages of the process. I would also like to thank Prof. Jeffrey T. Checkel for an excellent introduction to social constructivism in International Relations, Prof. Werner Christie Mathisen for his course on textual analysis, and Sunniva Engh for introducing me to Norwegian development aid history. You have all inspired me in the choice of perspective and object of study. Writing this thesis would not be possible without support and encouragement to overcome the many small and big challenges I have encountered. I am indebted to my fellow students, particularly Jonathan Amario and Ruben Røsler; my friends; and my parents. Last, but not least, Synnøve deserves my most heartfelt thanks for her patience and loving support. All the viewpoints presented, and all errors and inconsistencies, are solely my own responsibility. Øystein Haga Skånland Oslo, June 2008 iii Table of Content Acknowledgements .............................................................................................................. -

Revival and Society

REVIVAL AND SOCIETY An examination of the Haugian revival and its influence on Norwegian society in the 19th century. Magister Thesis in Sociology at the University of Oslo, 1978. By Alv Johan Magnus Grimerud 2312 Ottestad, Norway. Hans Nielsen Hauge, painted in 1800 Contents page Chapter 1: Introduction 3 Chapter 2: Hauge and his times 14 Chapter 3: Hauge and his message 23 Chapter 4: Hauge's work 36 Chapter 5: Revival in focus 67 Chapter 6: Social consequences of the revival 77 Chapter 7: The economic institution 83 Chapter 8: The political institution 95 Chapter 9: The religious institution 104 Chapter 10: Summing up 117 Literature 121 Foreword As I submit this thesis, it remains for me to give a special thank to my two supervisors, associate professor Sigurd Skirbekk and rector Otto Hauglin, for their personal involvement in my work. Our many talks and discussions have influenced this thesis. I also want to thank my fellow students for their constructive criticism during the writing periode. Rev. Einar Huglen has red the material on church history and given valuable corrections. A special thank goes to him. Elisabeth Engelsviken har accurately typed the whole manuscript, and Gro Bjerke has been of great help in drawing the figures. Thanks to both of you. Oslo, April 1, 1978. Alv J. Magnus PS: The painting above shows the only known original portrait of Hans Nielsen Hauge, probably made in Copenhagen in 1800. The English translation is done by Jenefer E. Hough, and the digital version by Steinar Thorvaldsen at Tromsø University College. A final part (Chapter 11-14) is only available in Norwegian, and is not included in this English version. -

1 Introduction

Notes 1 Introduction 1. Donald Macintyre, Narvik (London: Evans, 1959), p. 15. 2. See Olav Riste, The Neutral Ally: Norway’s Relations with Belligerent Powers in the First World War (London: Allen and Unwin, 1965). 3. Reflections of the C-in-C Navy on the Outbreak of War, 3 September 1939, The Fuehrer Conferences on Naval Affairs, 1939–45 (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1990), pp. 37–38. 4. Report of the C-in-C Navy to the Fuehrer, 10 October 1939, in ibid. p. 47. 5. Report of the C-in-C Navy to the Fuehrer, 8 December 1939, Minutes of a Conference with Herr Hauglin and Herr Quisling on 11 December 1939 and Report of the C-in-C Navy, 12 December 1939 in ibid. pp. 63–67. 6. MGFA, Nichols Bohemia, n 172/14, H. W. Schmidt to Admiral Bohemia, 31 January 1955 cited by Francois Kersaudy, Norway, 1940 (London: Arrow, 1990), p. 42. 7. See Andrew Lambert, ‘Seapower 1939–40: Churchill and the Strategic Origins of the Battle of the Atlantic, Journal of Strategic Studies, vol. 17, no. 1 (1994), pp. 86–108. 8. For the importance of Swedish iron ore see Thomas Munch-Petersen, The Strategy of Phoney War (Stockholm: Militärhistoriska Förlaget, 1981). 9. Churchill, The Second World War, I, p. 463. 10. See Richard Wiggan, Hunt the Altmark (London: Hale, 1982). 11. TMI, Tome XV, Déposition de l’amiral Raeder, 17 May 1946 cited by Kersaudy, p. 44. 12. Kersaudy, p. 81. 13. Johannes Andenæs, Olav Riste and Magne Skodvin, Norway and the Second World War (Oslo: Aschehoug, 1966), p. -

NORWAY AND. the WAR · September 1.939 - December 1940

DOCUMENTS ON -INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS . NORWAY AND. THE WAR · September 1.939 - December 1940. The Royal IMtitute of International .Affairs is an unofficial and non-political body, founded in 1920 to encourage and facilitate the seientifie study of international affairs. The Institute, as sueh, is precluded by its Royal Charter from expressing any opinion on any aspect of international affairs. .Any opinioM that may be expressed in this book on sueh subjects are not, therefore, the views of the Institute. DOCUMENTS ON INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS NORWAY AND THE WAR September 1939 December 1940 EDITED BY MONICA CURTIS OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON NEW YORK TORONTO 188Ved under the av.spicu of the Royal. li!Mil!IU of lntenlldioltal AJ!airB 1941 OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS A..ME.N ROUSE, E.C. 4 LONDON l!DilfBUI!.GH GLASGOW OW YORK !I:OBOIITO IIELBOUI!.l!fB CAPETOWN BOIIBAY CALCUTTA IIADBAS HUMPHREY MILFORD PUBLISIIEB TO TBE U!HVEBSITY PBINTKD 11'1 GBE&T DBl'r&Il'l PREFATORY NOTE OWING to war conditions it has not. been possible to publish the complete annual volumes of the Documents on International Affairs as ea:rly as usual. It has therefore been thought desirable to issue a separate advance publication relating to Norway and the War. This publication is to be regarded as forming part of the regular series of Documents on International Affairs and is conceived on the same lines. The fact that it has been compiled during the war nevertheless makes certain differences. Certain texts which it would be desirable to publish, especially those emanating from enemy or enemy-occupied countries, are not available, or can be found only in newspapers instead of in the more official form which would normally be used. -

Gustav Smedals Klipparkiv

Gustav Smedals klipparkiv Juristen Gustav Smedal (1888-1951) var en profilert person i det polare miljøet i Norge før krigen, og han involverte seg spesielt i Grønlandssaken på 1920- og 1930-tallet Arkivet består av avisutklipp innsamlet av Smedal selv Norsk Polarinstitutt Biblioteket Innledning Klipparkivet er på omtrent fem hyllemeter, sortert i bokser. Boksene inneholder mapper organisert av Gustav Smedal selv, inndelt i tema og ofte på dato. Klippene kommer i hovedsak norske aviser, men arkivet består også av utklipp fra nordisk og internasjonal presse. Enkelte tema er mye mer omfattende enn andre siden særlig Grønlandsspørsmål opptok Smedal. Likevel er det en stor spennvidde i arkivet fra norsk innenrikspolitikk til dansk kolonipolitikk, fra Arktis og Antarktis til strid om grensen mellom Danmark og Tyskland for å nevne noen. Hver enkel mappe er indeksert i listen under. Biblioteket kan i enkelte tilfeller tilby seg å kopiere innholdet i ønskede mapper. Der det finnes større mengder materiale lar dette seg dessverre ikke gjøre. Alle interesserte er imidlertid velkomne til å besøke biblioteket i Tromsø for nærmere studier. Tilleggsinformasjon utover Smedals egne notater er ført inn i parentes. Dette er i enkelte tilfeller gjort for å beskrive saker og personer. Boks 1 1. Det østgrønlandske suverenitetsspørsmål I Herunder Ishavsrådets offentliggjørelse av en henvendelse til Regjeringen av 5. mai 1931 og okkupasjonen av Eirik Raudes Land 1. januar – 21. mai 1931 2. Det østgrønlandske suverenitetsspørsmål II 30. mai – 29. juni 1931 Boks 2 3. Det østgrønlandske suverenitetsspørsmål III 30. juni – 4. juli 1931 4. Det østgrønlandske suverenitetsspørsmål IV 5. juli – 11. juli 1931 Boks 3 5. -

Forcible Entry and the German Invasion of Norway, 1940

FORCIBLE ENTRY AND THE GERMAN INVASION OF NORWAY, 1940 A thesis presented to the Faculty of the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF MILITARY ARTS AND SCIENCES Strategy by MICHAEL W. RICHARDSON, MAJ, USA B.S., University of Scranton, Scranton, PA, 1989 B.S., University of Scranton, Scranton, PA, 1989 M.S.B.A., Bucknell University, Lewisburg, PA, 1996 Fort Leavenworth, Kansas 2001 Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited. i MASTER OF MILITARY ART AND SCIENCE THESIS APPROVAL PAGE Name of Candidate: MAJ Michael W. Richardson Thesis Title: Forcible Entry and the German Invasion of Norway, 1940 Approved by: _______________________________________, Thesis Committee Chairman Marvin L. Meek, M.S., M.M.A.S. _______________________________________, Member Justin L.C. Eldridge, M.A., M.S.S.I. _______________________________________, Member Christopher R. Gabel, Ph.D. Accepted this 1st day of June 2001 by: _______________________________________, Director, Graduate Degree Programs Philip J. Brookes, Ph.D. The opinions and conclusions expressed herein are those of the student author and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College or any other governmental agency. (References to this study should include the foregoing statement.) 1 i 1 i 1 ABSTRACT FORCIBLE ENTRY AND THE GERMAN INVASION OF NORWAY, 1940, by MAJ Michael W. Richardson, 106 pages. The air-sea-land forcible entry of Norway in 1940 utilized German operational innovation and boldness to secure victory. The Germans clearly met, and understood, the conditions that were necessary to achieve victory. -

Nordic Narratives of the Second World War : National Historiographies Revisited

Nordic Narratives of the Second World War : National Historiographies Revisited Stenius, Henrik; Österberg, Mirja; Östling, Johan 2011 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Stenius, H., Österberg, M., & Östling, J. (Eds.) (2011). Nordic Narratives of the Second World War : National Historiographies Revisited. Nordic Academic Press. Total number of authors: 3 General rights Unless other specific re-use rights are stated the following general rights apply: Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal Read more about Creative commons licenses: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/ Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. LUND UNIVERSITY PO Box 117 221 00 Lund +46 46-222 00 00 Download date: 01. Oct. 2021 nordic narratives of the second world war Nordic Narratives of the Second World War National Historiographies Revisited Henrik Stenius, Mirja Österberg & Johan Östling (eds.) nordic academic press Nordic Academic Press P.O. Box 1206 SE-221 05 Lund, Sweden [email protected] www.nordicacademicpress.com © Nordic Academic Press and the authors 2011 Typesetting: Frederic Täckström www.sbmolle.com Cover: Jacob Wiberg Cover image: Scene from the Danish movie Flammen & Citronen, 2008.