Social Media: Instigating Factor Or Appropriated Tool?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Forecast 2017: Our Writers’ Predictions for the New Year Contents

Forecast 2017: Our Writers’ Predictions for the New Year Contents Egypt | 2 Lebanon | 5 Ayah Aman Haytham Mouzahem Shahira Amin North Africa | 5 Walaa Hussein Sarah Souli Gulf | 2 Giorgio Cafiero Palestine | 6 Ibrahim al-Hatlani Asmaa al-Ghoul Amal Nasser Daoud Kuttab Bruce Riedel Russia | 6 Yury Barmin Iran | 3 Vitaly Naumkin Maysam Bizaer Paul Saunders Rohollah Faghihi Maxim A. Suchkov Ali Hashem Saeid Jafari Syria | 7 Alireza Ramezani Asaad Hanna Mohammad Ali Shabani Kamal Sheikho Iraq | 4 Turkey | 7-8 Ali Mamouri Mustafa Akyol Mustafa Saadoun Ali Bayramoglu Saad Salloum Mahmut Bozarslan Cengiz Candar Israel | 4-5 Metin Gurcan Ben Caspit Semih Idiz Akiva Eldar Fehim Tastekin Shlomi Eldar Pinar Tremblay Mazal Mualem Amberin Zaman Uri Savir US | 8 Jordan | 5 Julian Pecquet Osama al-Sharif Laura Rozen Credits Cover: Mohammed Abed/AFP/Getty Images Page 3: Atta Kenare/AFP/Getty Images Page 4: Odd Andersen/AFP/Getty Images Page 6: Mahmud Hams/AFP/Getty Images Page 7: Reuters/Bassam Khabieh Designed by Aaron Schaffer. © 2016 Al-Monitor 1 on the issue of reconciliation with the Walaa Hussein Brotherhood. Sisi will nonetheless Egypt release small groups of detained Cairo hopes for many things in 2017, young men. Security problems are including an end to the economic Ayah Aman expected to continue in Sinai. crisis, control of the budget deficit, Shahira Amin stability of the local currency after In 2017, President Abdel Fattah the flotation of the pound, quelling al-Sisi will be heading Egypt’s I predict that in the year 2017, terrorism in Sinai and reaching a political administration for the third Egypt will see a surge in Islamist solution to the Renaissance Dam consecutive year, after years of political militancy with the insurgency in crisis. -

Utrecht University Vernacular Spaces in the Year of Dreams: A

Utrecht University Research Master’s Thesis Vernacular Spaces in the Year of Dreams: A Comparison Between Occupy Wall Street and the Egyptian Revolution Author: Supervisor: Alex Strete Prof. Dr. Ismee Tames Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Research Master’s of History Faculty of Humanities 15th June, 2021 Chapter Outline Table of Contents Introduction: The Global Occupation Movement of 2011 ............................................................. 1 Chapter One: The Vernacular Space as an Ideal Type ................................................................. 11 Chapter Two: “The People” of Tahrir Square .............................................................................. 35 Chapter Three: “The 99%” of Zuccotti Park ................................................................................ 52 Chapter Four: Tahrir Square and Zuccotti Park in Perspective .................................................... 67 Conclusion: Occupy Everything? ................................................................................................. 79 Bibliography ................................................................................................................................. 85 Abstract The year 2011 was a year of dreams. From the revolutionaries in the Arab Spring to the occupiers of Wall Street, people around the world organized in order to find alternative ways of living. However, they did not do so in a vacuum. Protesters were part of the same international -

In May 2011, Freedom House Issued a Press Release Announcing the Findings of a Survey Recording the State of Media Freedom Worldwide

Media in North Africa: the Case of Egypt 10 Lourdes Pullicino In May 2011, Freedom House issued a press release announcing the findings of a survey recording the state of media freedom worldwide. It reported that the number of people worldwide with access to free and independent media had declined to its lowest level in over a decade.1 The survey recorded a substantial deterioration in the Middle East and North Africa region. In this region, Egypt suffered the greatest set-back, slipping into the Not Free category in 2010 as a result of a severe crackdown preceding the November 2010 parliamentary elections. In Tunisia, traditional media were also censored and tightly controlled by government while internet restriction increased extensively in 2009 and 2010 as Tunisians sought to use it as an alternative field for public debate.2 Furthermore Libya was included in the report as one of the world’s worst ten countries where independent media are considered either non-existent or barely able to operate and where dissent is crushed through imprisonment, torture and other forms of repression.3 The United Nations Development Programme’s (UNDP) Arab Knowledge Report published in 2009 corroborates these findings and view the prospects of a dynamic, free space for freedom of thought and expression in Arab states as particularly dismal. 1 Freedom House, (2011): World Freedom Report, Press Release dated May 2, 2011. The report assessed 196 countries and territories during 2010 and found that only one in six people live in countries with a press that is designated Free. The Freedom of the Press index assesses the degree of print, broadcast and internet freedom in every country, analyzing the events and developments of each calendar year. -

In 1984 William Beeman Published a Brief but Fascinating Essay on The

Egypt's Media Ecology in a Time of Revolution Mark Allen Peterson Miami University Abstract: In 1984 William Beeman published a brief but useful essay on the media ecology of Iran before, during and after the revolution. After briefly discussing the relationship between interpersonal gossip ("the grapevine"), and state television and radio, he discusses the dramatic changes in the news media as the revolution progressed, only to settle back into its original role as a voice for the regime—albeit a new regime. The Egyptian uprising had new elements absent in the Iranian revolution, most notably social media and satellite television. Social media does not replace either "the grapevine" of networks of face-to- face interaction nor the monodirectional power of television (which was, in fact, somewhat less unitary than 1970s Iran because of satellite programming). Rather, it offers a way to extend the "grapevine" networks to link otherwise geographically separated individuals into an entirely new public sphere, on the one hand, and to appropriate, supplement, comment on and reframe other media on the other. The revolutionary media ecology of Egypt—in particular the ways various media index, image and influence one another—suggests that (unlike Iran) whatever the ultimate political outcome of the uprisings, the mediascape of Egypt after the revolution will be significantly different than it was before January 25. At times newly introduced mass media have produced revolutionary effects in the societal management of time and energy as they forged new spaces for themselves. Thus media are cultural forces as well as cultural objects. In operation, they produce specific cultural effects that cannot be easily predicted (Beeman 1984: 147). -

Al Jazeera's Expansion: News Media Moments and Growth in Australia

Al Jazeera’s Expansion: News Media Moments and Growth in Australia PhD thesis by publication, 2017 Scott Bridges Institute of Governance and Policy Analysis University of Canberra ABSTRACT Al Jazeera was launched in 1996 by the government of Qatar as a small terrestrial news channel. In 2016 it is a global media company broadcasting news, sport and entertainment around the world in multiple languages. Devised as an outward- looking news organisation by the small nation’s then new emir, Al Jazeera was, and is, a key part of a larger soft diplomatic and brand-building project — through Al Jazeera, Qatar projects a liberal face to the world and exerts influence in regional and global affairs. Expansion is central to Al Jazeera’s mission as its soft diplomatic goals are only achieved through its audience being put to work on behalf of the state benefactor, much as a commercial broadcaster’s profit is achieved through its audience being put to work on behalf of advertisers. This thesis focuses on Al Jazeera English’s non-conventional expansion into the Australian market, helped along as it was by the channel’s turning point coverage of the 2011 Egyptian protests. This so-called “moment” attracted critical and popular acclaim for the network, especially in markets where there was still widespread suspicion about the Arab network, and it coincided with Al Jazeera’s signing of reciprocal broadcast agreements with the Australian public broadcasters. Through these deals, Al Jazeera has experienced the most success with building a broadcast audience in Australia. After unpacking Al Jazeera English’s Egyptian Revolution “moment”, and problematising the concept, this thesis seeks to formulate a theoretical framework for a news media turning point. -

Islamist Reactions to the Biden Presidency in the Middle East

ISSUE BRIEF 04.13.21 Islamist Reactions to the Biden Presidency in the Middle East A.Kadir Yildirim, Ph.D., Fellow for the Middle East For Islamists, the Trump administration ISLAMIST GROUPS’ MESSAGING embodied the worst of American policy toward Islam, Muslims, and Muslim- ON BIDEN majority countries. The Muslim ban, The Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood has been express support for Israeli policies in among the most enthusiastic about the the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and the Biden administration. Ibrahim Munir, the embrace of Islamophobic discourse leave deputy supreme guide of the Brotherhood, little doubt that Muslims in general and welcomed the change in U.S. leadership Islamists in particular were discontented and called on the United States to “return with the Trump presidency. to the values of democracy and respect the How have Islamists—as the relentless will of nations.”1 self-proclaimed defenders of Islam and The Brotherhood’s interest in Biden is Muslims—reacted to the Biden presidency? firmly rooted in the group’s desire to see a Do Islamists’ ideological leanings dictate change in the Egyptian political landscape. their response to Biden in the form of a In particular, the Brotherhood hopes for warm welcome, or do their tangible and This is familiar terrain the Biden administration to gain greater for the Brotherhood. political interests shape their reactions? awareness of the ongoing repressive Statements by Islamist organizations or environment in Egypt and to pressure The group has always their leadership reveal that Islamists around Egyptian President Abdel Fattah al-Sisi to claimed to speak on the Middle East filter Biden’s electoral victory change his policy toward the Brotherhood behalf of the people through their organizational self-interests. -

Framing of Political Forces in Liberal, Islamist and Government Newspapers in Egypt: a Content Analysis

American University in Cairo AUC Knowledge Fountain Theses and Dissertations 6-1-2012 Framing of political forces in liberal, islamist and government newspapers in Egypt: A content analysis Noha El-Nahass Follow this and additional works at: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds Recommended Citation APA Citation El-Nahass, N. (2012).Framing of political forces in liberal, islamist and government newspapers in Egypt: A content analysis [Master’s thesis, the American University in Cairo]. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/296 MLA Citation El-Nahass, Noha. Framing of political forces in liberal, islamist and government newspapers in Egypt: A content analysis. 2012. American University in Cairo, Master's thesis. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/296 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by AUC Knowledge Fountain. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AUC Knowledge Fountain. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The American University in Cairo School of Global Affairs and Public Policy Framing of Political Forces in Liberal, Islamist and government newspapers in Egypt: A content analysis A Thesis Submitted to Journalism & Mass Communication department In partial fulfillment of the requirements for The degree of Master of Arts By Noha El-Nahass Under the supervision of Dr. Naila Hamdy Spring 2016 1 Dedication I dedicate this thesis to the journalists who lost their lives while covering the political turbulences in Egypt, may their sacrifices enlighten the road and give the strength to their colleagues to continue reflecting the truth and nothing but the truth. -

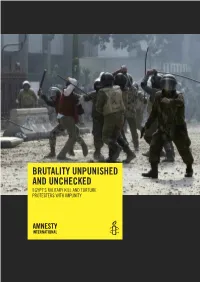

Brutality Unpunished and Unchecked

brutality unpunished and unchecked EGYPT’S MILITARY KILL AND TORTURE PROTESTERS WITH IMPUNITY amnesty international is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the universal declaration of human rights and other international human rights standards. we are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2012 by amnesty international ltd peter benenson house 1 easton street london wc1X 0dw united kingdom © amnesty international 2012 index: mde 12/017/2012 english original language: english printed by amnesty international, international secretariat, united kingdom all rights reserved. this publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. the copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. to request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover phot o: egyptian soldiers beating a protester during clashes near the cabinet offices by cairo’s tahrir square on 16 december 2011. © mohammed abed/aFp/getty images amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................5 2. MASPERO PROTESTS: ASSAULT OF COPTS.............................................................11 3. CRACKDOWN ON CABINET OFFICES SIT-IN.............................................................17 4. -

![Égypte/Monde Arabe, 13 | 2015, « Nouvelles Luttes Autour Du Genre En Egypte Depuis 2011 » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 10 Novembre 2017, Consulté Le 24 Septembre 2020](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5053/%C3%A9gypte-monde-arabe-13-2015-%C2%AB-nouvelles-luttes-autour-du-genre-en-egypte-depuis-2011-%C2%BB-en-ligne-mis-en-ligne-le-10-novembre-2017-consult%C3%A9-le-24-septembre-2020-2155053.webp)

Égypte/Monde Arabe, 13 | 2015, « Nouvelles Luttes Autour Du Genre En Egypte Depuis 2011 » [En Ligne], Mis En Ligne Le 10 Novembre 2017, Consulté Le 24 Septembre 2020

Égypte/Monde arabe 13 | 2015 Nouvelles luttes autour du genre en Egypte depuis 2011 New gender-related Struggles in Egypt since 2011 Leslie Piquemal (dir.) Édition électronique URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ema/3492 DOI : 10.4000/ema.3492 ISSN : 2090-7273 Éditeur CEDEJ - Centre d’études et de documentation économiques juridiques et sociales Édition imprimée Date de publication : 10 novembre 2015 ISBN : 9782905838865 ISSN : 1110-5097 Référence électronique Leslie Piquemal (dir.), Égypte/Monde arabe, 13 | 2015, « Nouvelles luttes autour du genre en Egypte depuis 2011 » [En ligne], mis en ligne le 10 novembre 2017, consulté le 24 septembre 2020. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/ema/3492 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/ema.3492 Ce document a été généré automatiquement le 24 septembre 2020. © Tous droits réservés 1 Depuis le soulèvement de 2011 en Égypte, les problématiques de genre ont émergé sous différentes formes dans le cadre des mouvements protestataires – révolutionnaires, réactionnaires – et plus largement, dans celui des transformations sociales se produisant autour et entre ces vagues de mobilisation. Alors que les relations entre citoyens et autorités étatiques ont été contestées, modifiées, puis repoussées dans une direction réactionnaire, comment les relations de genre ont-elles été contestées depuis 2011 ? Quels nouveaux imaginaires, quels nouveaux rôles et identités ont été revendiqués ? Quelles mobilisations se sont construites face à l’essor saisissant des violences sexistes dans l’espace public ? Quatre ans après le début de la période révolutionnaire, ce numéro d’Égypte/Monde arabe explore les nouvelles luttes liées au genre en Égypte au prisme de la sociologie, l’anthropologie et la science politique. -

Degruyter Opphil Opphil-2020-0112 462..477 ++

Open Philosophy 2020; 3: 462–477 Philosophy of the City Mathew Crippen*, Vladan Klement Architectural Values, Political Affordances and Selective Permeability https://doi.org/10.1515/opphil-2020-0112 received April 21, 2020; accepted July 21, 2020 Abstract: This article connects value-sensitive design to Gibson’saffordance theory: the view that we perceive in terms of the ease or difficulty with which we can negotiate space. Gibson’s ideas offer a nonsubjectivist way of grasping culturally relative values, out of which we develop a concept of political affordances, here understood as openings or closures for social action, often implicit. Political affordances are equally about environments and capacities to act in them. Capacities and hence the severity of affordances vary with age, health, social status and more. This suggests settings are selectively permeable, or what postphenomenologists call multistable. Multistable settings are such that a single physical location shows up differently – as welcoming or hostile – depending on how individuals can act on it. In egregious cases, authoritarian governments redesign politically imbued spaces to psychologically cordon both them and the ideologies they represent. Selective permeability is also orchestrated according to business interests, which is symptomatic of commercial imperatives increasingly dictating what counts as moral and political goods. Keywords: architectural values, moral and political philosophy, multistability, political affordances, postphenomenology, pragmatism, selective permeability, sociology of place, urban planning, value- sensitive design 1 Introduction Everyday life is valuative, that is, organized around emotions, interests and aesthetics.¹ The behavioral neuroscientist and philosopher Jay Schulkin, for example, identifies emotion with cognitive systems that “pervade aesthetic judgment.”² The environmental psychologists Rachel and Stephen Kaplan similarly argue that aesthetic and affective sensitivities to environments undergird cognition and perception.³ They locate their position loosely within J. -

MESA ANNUAL MEETING 2011 December 1‐4 Washington Marriott Wardman Park Hotel, Washington DC

MESA ANNUAL MEETING 2011 December 1‐4 Washington Marriott Wardman Park Hotel, Washington DC The following listing of CMES and Harvard Affiliated speakers was compiled from the MESA Program that was posted in October. Please note that there may have been updates since this time that we were unable to include. For the most current information on times and locations of these panels, visit: http://www.mesa.arizona.edu/pdf/11_preliminary_program.pdf Pages 1‐2 Harvard Affiliate Listing with session times Pages 3‐46 MESA Program with Harvard Affiliate names highlighted Harvard Affiliate listing with day(s)/time(s) of MESA sessions Harvard Faculty: . Doherty, Gareth (Lecturer in Landscape Architecture & Urban Planning / Design) – Fri, 2‐4 . Frye, Richard N. (Aga Khan Professor of Iranian, Emeritus) – Sat, 5‐7 . Kafadar, Cemal (Vehbi Koç Professor of Turkish Studies) – Fri, 8:30‐10:30 . Miller, Susan Gilson (CMES Associate) – Sat, 11‐1; Sat, 5‐7 . Mottahedeh, Roy (Gurney Professor of History) – Fri, 8:30‐10:30 . Najmabadi, Afsaneh (Professor of Women's Studies; Professor of History) – Sun, 11‐1 . Owen, E. Roger (A.J. Meyer Professor of Middle Eastern History) – Thurs, 5‐7; Fri, 4:30‐6:30 . Zeghal, Malika (Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal Professor in Contemporary Islamic Thought & Life) – Sat, 11‐1 Harvard Students: . Balbale, Abigail Krasner (G7 History/MES) – Sat, 2:30‐4:30 . Egemen, Melih (History) – Sat, 11‐1 . Gerbakher, Ilona (G1 Divinity) – Sat, 2:30‐4:30 . Gordon, Jennifer (G4 History/MES) – Fri, 8:30‐10:30 . Kibler, Bethany (G1 Anthropology/MES) – Sun, 1:30‐3:30 . Li, Darryl (G8 Anthropology/MES) – Fri, 2‐4 . -

Cairo & the Egyptian Museum

© Lonely Planet Publications 107 Cairo CAIRO Let’s address the drawbacks first. The crowds on a Cairo footpath make Manhattan look like a ghost town. You will be hounded by papyrus sellers at every turn. Your life will flash before your eyes each time you venture across a street. And your snot will run black from the smog. But it’s a small price to pay, to visit the city Cairenes call Umm ad-Dunya – ‘the mother of the world’. This city has an energy, palpable even at three in the morning, like no other. It’s the product of its 20 million inhabitants waging a battle against the desert and winning (mostly), of 20 million people simultaneously crushing the city’s infrastructure under their collective weight and lifting the city’s spirit up with their uncommon graciousness and humour. One taxi ride can span millennia, from the resplendent mosques and mausoleums built at the pinnacle of the Islamic empire, to the 19th-century palaces and grand avenues (which earned the city the nickname ‘Paris on the Nile’), to the brutal concrete blocks of the Nasser years – then all the way back to the days of the pharaohs, as the Pyramids of Giza hulk on the western edge of the city. The architectural jumble is smoothed over by an even coating of beige sand, and the sand is a social equalizer as well: everyone, no matter how rich, gets dusty when the spring khamsin blows in. So blow your nose, crack a joke and learn to look through the dirt to see the city’s true colours.