Bridges Over the Nile

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Social Media: Instigating Factor Or Appropriated Tool?

Social media: Instigating factor or appropriated tool? Assessing the level of agency ascribed to the use of social media for the organization and coordination of the 25th January Revolution in Egypt Master thesis Author: Ardan Kockelkoren Student number: S4159519 University: Radboud University Nijmegen Date: 27-06-2013 Supervisors dr. H.W. Bomert and dr. G.M. Millar 1 Abstract This research addresses the perceived importance of the use of social media for the organization of the 25th of January, 2011, revolution in Egypt. Individual face-to-face semi-structured interviews and face-to-face collected written surveys were the main research methods used to acquire the research data. This research shows that there is a relationship between the use of social media and the way in which the revolution has unfolded in Egypt. Social media is perceived to have made the revolutionary process unfold in a faster pace and the initial organization and coordination trough the social media platforms have made the revolution a leaderless revolution. Social media played a significant role but it should not be seen as an instigating factor, however. The role that the social media platforms played, must be seen in a wider framework of interdependent processes and factors that are also perceived as important to the unfolding of the revolutionary process by the Egyptian people. Significant differences have been found between different population groups in how important they perceive the use of social media for the organization of the revolution. Egyptians with an university degree, who have an internet connection at home and who have a Facebook account, find the use of social media significantly more important for the organization of the revolution in Egypt than others. -

Utrecht University Vernacular Spaces in the Year of Dreams: A

Utrecht University Research Master’s Thesis Vernacular Spaces in the Year of Dreams: A Comparison Between Occupy Wall Street and the Egyptian Revolution Author: Supervisor: Alex Strete Prof. Dr. Ismee Tames Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the Research Master’s of History Faculty of Humanities 15th June, 2021 Chapter Outline Table of Contents Introduction: The Global Occupation Movement of 2011 ............................................................. 1 Chapter One: The Vernacular Space as an Ideal Type ................................................................. 11 Chapter Two: “The People” of Tahrir Square .............................................................................. 35 Chapter Three: “The 99%” of Zuccotti Park ................................................................................ 52 Chapter Four: Tahrir Square and Zuccotti Park in Perspective .................................................... 67 Conclusion: Occupy Everything? ................................................................................................. 79 Bibliography ................................................................................................................................. 85 Abstract The year 2011 was a year of dreams. From the revolutionaries in the Arab Spring to the occupiers of Wall Street, people around the world organized in order to find alternative ways of living. However, they did not do so in a vacuum. Protesters were part of the same international -

Al Jazeera's Expansion: News Media Moments and Growth in Australia

Al Jazeera’s Expansion: News Media Moments and Growth in Australia PhD thesis by publication, 2017 Scott Bridges Institute of Governance and Policy Analysis University of Canberra ABSTRACT Al Jazeera was launched in 1996 by the government of Qatar as a small terrestrial news channel. In 2016 it is a global media company broadcasting news, sport and entertainment around the world in multiple languages. Devised as an outward- looking news organisation by the small nation’s then new emir, Al Jazeera was, and is, a key part of a larger soft diplomatic and brand-building project — through Al Jazeera, Qatar projects a liberal face to the world and exerts influence in regional and global affairs. Expansion is central to Al Jazeera’s mission as its soft diplomatic goals are only achieved through its audience being put to work on behalf of the state benefactor, much as a commercial broadcaster’s profit is achieved through its audience being put to work on behalf of advertisers. This thesis focuses on Al Jazeera English’s non-conventional expansion into the Australian market, helped along as it was by the channel’s turning point coverage of the 2011 Egyptian protests. This so-called “moment” attracted critical and popular acclaim for the network, especially in markets where there was still widespread suspicion about the Arab network, and it coincided with Al Jazeera’s signing of reciprocal broadcast agreements with the Australian public broadcasters. Through these deals, Al Jazeera has experienced the most success with building a broadcast audience in Australia. After unpacking Al Jazeera English’s Egyptian Revolution “moment”, and problematising the concept, this thesis seeks to formulate a theoretical framework for a news media turning point. -

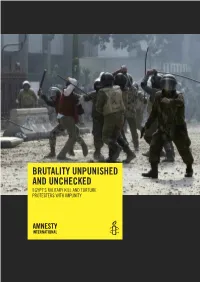

Brutality Unpunished and Unchecked

brutality unpunished and unchecked EGYPT’S MILITARY KILL AND TORTURE PROTESTERS WITH IMPUNITY amnesty international is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the universal declaration of human rights and other international human rights standards. we are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2012 by amnesty international ltd peter benenson house 1 easton street london wc1X 0dw united kingdom © amnesty international 2012 index: mde 12/017/2012 english original language: english printed by amnesty international, international secretariat, united kingdom all rights reserved. this publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. the copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. to request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover phot o: egyptian soldiers beating a protester during clashes near the cabinet offices by cairo’s tahrir square on 16 december 2011. © mohammed abed/aFp/getty images amnesty.org CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................5 2. MASPERO PROTESTS: ASSAULT OF COPTS.............................................................11 3. CRACKDOWN ON CABINET OFFICES SIT-IN.............................................................17 4. -

Degruyter Opphil Opphil-2020-0112 462..477 ++

Open Philosophy 2020; 3: 462–477 Philosophy of the City Mathew Crippen*, Vladan Klement Architectural Values, Political Affordances and Selective Permeability https://doi.org/10.1515/opphil-2020-0112 received April 21, 2020; accepted July 21, 2020 Abstract: This article connects value-sensitive design to Gibson’saffordance theory: the view that we perceive in terms of the ease or difficulty with which we can negotiate space. Gibson’s ideas offer a nonsubjectivist way of grasping culturally relative values, out of which we develop a concept of political affordances, here understood as openings or closures for social action, often implicit. Political affordances are equally about environments and capacities to act in them. Capacities and hence the severity of affordances vary with age, health, social status and more. This suggests settings are selectively permeable, or what postphenomenologists call multistable. Multistable settings are such that a single physical location shows up differently – as welcoming or hostile – depending on how individuals can act on it. In egregious cases, authoritarian governments redesign politically imbued spaces to psychologically cordon both them and the ideologies they represent. Selective permeability is also orchestrated according to business interests, which is symptomatic of commercial imperatives increasingly dictating what counts as moral and political goods. Keywords: architectural values, moral and political philosophy, multistability, political affordances, postphenomenology, pragmatism, selective permeability, sociology of place, urban planning, value- sensitive design 1 Introduction Everyday life is valuative, that is, organized around emotions, interests and aesthetics.¹ The behavioral neuroscientist and philosopher Jay Schulkin, for example, identifies emotion with cognitive systems that “pervade aesthetic judgment.”² The environmental psychologists Rachel and Stephen Kaplan similarly argue that aesthetic and affective sensitivities to environments undergird cognition and perception.³ They locate their position loosely within J. -

Cairo & the Egyptian Museum

© Lonely Planet Publications 107 Cairo CAIRO Let’s address the drawbacks first. The crowds on a Cairo footpath make Manhattan look like a ghost town. You will be hounded by papyrus sellers at every turn. Your life will flash before your eyes each time you venture across a street. And your snot will run black from the smog. But it’s a small price to pay, to visit the city Cairenes call Umm ad-Dunya – ‘the mother of the world’. This city has an energy, palpable even at three in the morning, like no other. It’s the product of its 20 million inhabitants waging a battle against the desert and winning (mostly), of 20 million people simultaneously crushing the city’s infrastructure under their collective weight and lifting the city’s spirit up with their uncommon graciousness and humour. One taxi ride can span millennia, from the resplendent mosques and mausoleums built at the pinnacle of the Islamic empire, to the 19th-century palaces and grand avenues (which earned the city the nickname ‘Paris on the Nile’), to the brutal concrete blocks of the Nasser years – then all the way back to the days of the pharaohs, as the Pyramids of Giza hulk on the western edge of the city. The architectural jumble is smoothed over by an even coating of beige sand, and the sand is a social equalizer as well: everyone, no matter how rich, gets dusty when the spring khamsin blows in. So blow your nose, crack a joke and learn to look through the dirt to see the city’s true colours. -

On Revolutionary Street Screenings in Egypt

International Journal of Communication 9(2015), 2903–2921 1932–8036/20150005 Making Media Public: On Revolutionary Street Screenings in Egypt NINA GRØNLYKKE MOLLERUP1 Roskilde University, Denmark SHERIEF GABER Mosireen, Egypt This article focuses on two related street screening initiatives, Tahrir Cinema and Kazeboon, which took place in Egypt mainly between 2011 and 2013. Based on long- term ethnographic studies and activist work, we explore street screenings as place- making and describe how participants at street screenings knew with rather than from the screenings. With the point of departure that participants’ experiences of the images cannot be understood detached from their experiences of everything around the images, we argue that Egyptian revolutionary street screenings enabled particular paths to knowledge because they made media engage with and take place within everyday spaces that the revolution aims to liberate and transform, and because the screenings’ public and illegal manner at times embodied events portrayed in the images. Keywords: Egypt, revolution, street screenings, information activism, media Introduction Tahrir Cinema, summer, 2011 (Sherief Gaber’s experience): Tahrir Square is full once again. The tents in the middle of the square are in place, and people are determined not to leave before Mubarak is held accountable and the hundreds killed and thousands wounded are given justice. I hear from friends about a plan to set up a screen in the square and show footage collected over the past months to remind people why we are here. And to show others who may not have seen these images. I go, without much to offer but happy to help. -

S T U D I M a G E B

UNIOR D.A.A.M. Centro di Studi Mag·rebini REBINI ‚ STUDI MAG STUDI Gender Mobility and Social Activism Gender Mobility and Social Emerging Actors in Post-Revolutionary North Africa Actors in Post-Revolutionary North Emerging Nuova Serie Vol. XIV - XV Tomo I Napoli 2016 - 2017 UNIOR D.A.A.M. Centro di Studi Mag·rebini UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI NAPOLI “L’ORIENTALE” DIPARTIMENTO ASIA, AFRICA E MEDITERRANEO Centro di Studi Magrebini· STUDI MAG‚REBINI Nuova Serie Volumi XIV - XV Napoli 2016 - 2017 REBINI ‚ EMERGING ACTORS IN POST-REVOLUTIONARY NORTH AFRICA Gender Mobility and Social Activism Preface by STUDI MAG STUDI Gilbert ACHCAR Edited by Anna Maria DI TOLLA & Ersilia FRANCESCA Nuova Serie Vol. XIV - XV Tomo I Tomo I ISSN: 0585-4954 Napoli ISBN: 978-88-6719-155-0 2016 - 2017 UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI NAPOLI “L’ORIENTALE” DIPARTIMENTO ASIA, AFRICA E MEDITERRANEO Centro di Studi Magrebini· STUDI MAGREBINI‚ Nuova Serie Volumi XIV - XV Napoli 2016 -2017 EMERGING ACTORS IN POST-REVOLUTIONARY NORTH AFRICA Gender Mobility and Social Activism Preface by Gilbert ACHCAR Edited by Anna Maria DI TOLLA & Ersilia FRANCESCA Tomo I UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI NAPOLI “L’ORIENTALE” DIPARTIMENTO ASIA, AFRICA E MEDITERRANEO CENTRO DI STUDI MAG‚REBINI Presidente: Sergio BALDI Direttore della rivista: Agostino CILARDO &RQVLJOLR6FLHQWLÀFR6HUJLR%$/',$QQD0DULD',72//$0RKD ENNAJ, Ersilia FRANCESCA$KPHG+$%2866(O+RXVVDLQ (/028-$+,'$EGDOODK(/02817$66,52XDKPL28/' BRAHAM, Nina PAWLAK, Fatima SADIQI Consiglio Editoriale: Flavia AIELLO, Orianna CAPEZIO, Carlo DE ANGELO, Roberta DENARO Piazza S. Domenico Maggiore , 12 Palazzo Corigliano 80134 NAPOLI Direttore Responsabile: Agostino Cilardo Autorizzazione del Tribunale di Napoli n. -

Arab Authoritarianism and US Foreign Policy

Lingnan University Digital Commons @ Lingnan University Bachelor of Social Sciences – Senior Theses Undergraduate Open Access Dissertations 2014 Arab authoritarianism and US foreign policy Ki Chun LUK Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.ln.edu.hk/socsci_fyp Part of the American Politics Commons, International Relations Commons, and the Peace and Conflict Studies Commons Recommended Citation Luk, K. C. (2014). Arab authoritarianism and US foreign policy (UG dissertation, Lingnan University, Hong Kong). Retrieved from http://commons.ln.edu.hk/socsci_fyp/7 This UG Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Undergraduate Open Access Dissertations at Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bachelor of Social Sciences – Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Lingnan University. Arab authoritarianism and US foreign policy A Thesis Presented to: The Program Office of Social Sciences of Lingnan University in partial fulfilment for the requirement of the Degree in Bachelor of Social Sciences Submitted by: Luk, Ki Chun (1170101) Submitted to: Dr. Zhang Baohui 2014 1 Table of Content 1. Chapter I: 1.1 Abstract 1.2 Research background and questions 1.3 Hypothesises 1.4 Research significance 1.5 Methodologies 1.6 Literature review and critical analysis 1.6.1 national interest analysis 1.6.2 national-interest analysis: Asset mobility approach 1.6.3 national-interest analysis: international conditions analysis 1.6.4 The Foreign policy model: US grand strategy 1.6.5 US domestic politics analysis 1.6.5.1 Congressional/senior security advisors’ unity in opinions 1.6.5.2 The strength of lobbying activities 1.6.5.3 Mass media and American public opinion during foreign policy crisis 1.6.6 Critical analysis of the realist national-interest framework and the US grand strategy neoclassical realist model, asset mobility approach, international conditions analysis and US Domestic politics analysis 2. -

Modern Art in Egypt and Constellational Modernism: a New Approach to Global Modern Art

MAVCOR Journal (mavcor.yale.edu) Modern Art in Egypt and Constellational Modernism: A New Approach to Global Modern Art Alex Dika Seggerman Collection in complement to Alex Dika Seggerman’s Modernism on the Nile: Art in Egypt Between the Islamic and the Contemporary, The University of North Carolina Press, 2019. Fig. 1 Pascal Sebah Photography Studio, Portrait of Princess Nazli, ca. 1890, albumen cabinet card, collection of Barry Iverson, Cairo, Egypt My book, Modernism on the Nile: Art in Egypt between the Islamic and the Contemporary analyzes the modernist art movement that arose in Cairo and Alexandria from the late-nineteenth century through the 1960s. By incorporating the previously undervalued artists of this understudied region into the modernist canon, I challenge the prevailing understanding that modern art is largely a Euro-American phenomenon. As such, this book serves as post-colonial critique, providing new ways of understanding Egypt’s visual culture, as well as modernism, as a global phenomenon. In what follows, I introduce my reader to the problematic intellectual paradigms of modernism in art history and detail the new approach that I develop in my book for modern Egyptian art. I then analyze a selection of artworks, which are not included in the book, and present how they relate to the overarching themes detailed below. The paucity of knowledge about modern art produced outside of Western Europe MAVCOR Journal (mavcor.yale.edu) and America prompted me to take a deep dive into the art history of modern Egypt. Over the last ten years, I have located and evaluated primary sources such as state correspondence, art criticism, and physical artworks, approaching them as part of the global phenomenon of modernism. -

Tunisia, Egypt, and the Unmaking of an Era

REVOLUTION IN THE ATUNISIA,RA EGYPBT, AND WOTHE UNMAKINGR OFLD AN ERA A SPECIAL REPORT FROM '03&*(/10-*$:t3&70-65*0/*/5)&"3"#803-%t'03&*(/10-*$:t3&70-65*0/*/5)&"3"#803-%TUNISIA © 2011 F!"#$%& P!'$() Published by the Slate Group, a division of !e Washington Post Company www.foreignpolicy.com '03&*(/10-*$:t3&70-65*0/*/5)&"3"#803-%t'03&*(/10-*$:t3&70-65*0/*/5)&"3"#803-%RUMBLINGS REVOLUTION IN THE ARAB WORLD TUNISIA, EGYPT, AND THE UNMAKING OF AN ERA Exclusive coverage of the turmoil in the Middle East — as it’s happening. By the world’s leading experts and journalists on the ground. A Middle East Channel Production Edited by Marc Lynch, Susan B. Glasser, and Blake Hounshell Produced by Britt Peterson Art-directed by Dennis Brack with assistance from Erin Aulov and Andrew Hughey I '03&*(/10-*$:t3&70-65*0/*/5)&"3"#803-%t'03&*(/10-*$:t3&70-65*0/*/5)&"3"#803-%RUMBLINGS “What is the perfect day for Hosni Mubarak? A day when nothing happens.” —Egyptian joke, December 2010 “A bunch of incognizant, ine"ective young people” —Egyptian Interior Minister Habib al-Adly on the Tahrir Square protesters, Jan. 25, 2011 II '03&*(/10-*$:t3&70-65*0/*/5)&"3"#803-%t'03&*(/10-*$:t3&70-65*0/*/5)&"3"#803-%RUMBLINGS I!"#$%&'"($! By Blake Hounshell and Marc Lynch 1 C)*+",# - R&./0(!12 $3 R,4$0&"($! Introduction 10 January 2010: A5er Pharaoh By Issandr El Amrani 11 June 2010: Even Iran’s Regime Hates Iran’s Regime By Karim Sadjadpour 13 June 2010: 6e Hollow Arab Core By Marc Lynch 16 June 2010: “Reform,” Saudi Style By Toby C. -

11. H Salama Tahrir Square

International Journal of Architectural Research Hussam Hussein Salama TAHRIR SQUARE A Narrative of a Public Space Hussam Hussein Salama Department of Architecture and Urban Planning Qatar University, Doha, Qatar [email protected] Abstract This paper investigates the patterns of public discourse that occurred in Tahrir Square during the 18 days of the Egyptian Revolution. For protestors Tahrir Square became an urban utopia, a place of community engagement, collective projects, social discourse, and most importantly, freedom of speech and expression. This paper traces these forms of spatial adaptation, and the patterns of social organization and discourse that emerged in the square during that period. The paper builds on Henri Lefebvre’s interpretation of space and his three dimensional conceptualization: the perceived, the conceived, and the lived. Keywords: Tahrir Square; public space; Henri Lefebvre; public discourse; space adaptation. INTRODUCTION For decades, the notion of public space has been conceived by average Egyptians as the space that is owned by the government. The term melk el hokooma (property of government) was commonly used to refer to the public realm. Egyptians were made to believe that “public” equates “governmental,” a conception that shaped their mental image of public space for decades. People were deprived of any social or political practices within the public realm. Under the Egyptian Emergency Laws, the agglomeration of more than five people in a public space could be considered a protest that threatens public safety and can lead to prosecution. On its part, the government tended to minimize people’s presence in public spaces and in particular, plazas, by either fencing them or changing their land use.