Wright, Natalie Francesca.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literature, Politics, and the University, 1932–19651

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by King's Research Portal King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1093/english/efw011 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Hutton, A. (2016). An English School for the Welfare State: Literature, Politics, and the University, 1932-1965. ENGLISH, 65(248), 3-34. https://doi.org/10.1093/english/efw011 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

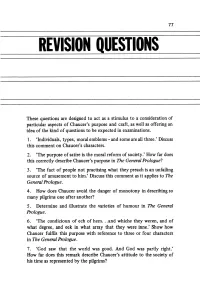

Revision Questions

77 REVISION QUESTIONS These questions are designed to act as a stimulus to a consideration of particular aspects of Chaucer's purpose and craft, as well as offering an idea of the kind of questions to be expected in examinations. 1. 'Individuals, types, moral emblems - and some are all three.' Discuss this comment on Chaucer's characters. 2. 'The purpose ofsatire is the moral reform ofsociety.' How far does this correctly describe Chaucer's purpose in The General Prologue? 3. 'The fact of people not practising what they preach is an unfailing source of amusement to him.' Discuss this comment as it applies to The General Prologue. 4. How does Chaucer avoid the danger of monotony in describing so many pilgrims one after another? 5. Determine and illustrate the varieties of humour in The General Prologue. 6. 'The condicioun of ech of hem ...and whiche they weren, and of what degree, and eek in what array that they were inne.' Show how Chaucer fulfils this purpose with reference to three or four characters in The General Prologue. 7. 'God saw that the world was good. And God was partly right.' How far does this remark describe Chaucer's attitude to the society of his time as represented by the pilgrims? 79 FURTHER READING Long book lists can be both daunting and useless, if a student cannot decide what will be of immediate interest to him. For this reason this bibliography has been kept very short. Its purpose is merely to point in one or two useful directions; further signposts are plentiful as soon as any of these books are examined. -

Annual Report 2006-2008 FINAL

WEATHERHEAD CENTER FOR INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS H A R V A R D U N I V E R S I T Y two2006-2007 thousand six – two thousand seven ANNUAL REPORTS two2007-2008 thousand seven – two thousand eight 1737 Cambridge Street • Cambridge, MA 02138 www.wcfia.harvard.edu TABLE OF CONTENTS PEOPLE 2 Advisory Committee 2 Executive Committee 2 Administration 3 RESEARCH ACTIVITIES 5 Small Grants for Faculty Research Projects 5 Medium Grants for Faculty Research Projects 5 Large Grants for Faculty Research Projects 5 Large Grants for Faculty Research Semester Leaves 6 Junior Faculty Synergy Semester Leaves 7 Distinguished Lecture Series 8 Weatherhead Initiative in International Affairs 8 CONFERENCES 10 STUDENT PROGRAMS 31 RESEARCH SEMINARS 45 Africa Research Seminar 45 Challenges Of The Twenty-First Century: European And American Perspectives 46 Communist and Postcommunist Countries Seminar 47 Comparative Politics Research Workshop 47 Comparative Politics Seminar 52 Cultural Politics: Interdisciplinary Pespectives Seminar 52 Director’s Faculty Seminar 53 Economic Growth and Development Workshop 53 Economic History Workshop 54 Ethics And International Relations Seminar 56 Faculty Discussion Group On Political Economy 56 Futue of War Seminar 63 Herbert C. Kelman Seminar on International Conflict Analysis and Resolution 63 International Business Seminar 65 International Economics Workshop 66 International History Seminar 68 International Law and International Relations Seminar 70 Middle East Seminar 71 Political Violence and Civil War 73 Religion and Society 75 Research Workshop in International Relations 75 Research Workshop on Political Economy 77 Science and Society Seminar 83 South Asia Seminar 84 Southeast Asia Security and International Relations 85 Transatlantic Relations Semimar 85 U.S. -

Sharon Marcus

x SHARON MARCUS COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY • DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH AND COMPARATIVE LITERATURE • NEW YORK, NY 10027 256 WEST 10TH STREET, 1B • NEW YORK, NY 10014 • 646.981.7194 • [email protected] EDUCATION 1995 Ph.D., The Johns Hopkins University, Humanities Center, Comparative Literature 1986 B.A., Brown University, Comparative Literature (Honors) EMPLOYMENT 2014– 2017 Dean of Humanities, Arts and Sciences, Columbia University (3-year term) 2008– PRESENT Orlando Harriman Professor, English and Comparative Literature, Columbia University 2007-2008 Professor, English and Comparative Literature, Columbia University 2003-2007 Associate Professor, English and Comparative Literature, Columbia University 2003– PRESENT Affiliated Faculty, Institute for Comparative Literature and Society, Columbia University 2003– PRESENT Affiliated Faculty, Institute for Research on Women and Gender, Columbia University 1998-2003 Associate Professor, English, University of California, Berkeley 1994-1998 Assistant Professor, English, University of California, Berkeley FELLOWSHIPS, GRANTS, AND PRIZES 2017-18 John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation fellowship 2017-18 Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study fellowship 2017-18 Harry Ransom Center Research Fellowship in the Humanities 2015-17 Mellon Grant for Center for Spatial Research, Co-PI (with Laura Kurgan), 2016 Provost's MOOC Grant, "The Great Novels," Co-PI (with Nicholas Dames) 2015-17 ACLS Public Fellows Grant for Public Books, Co-PI (with Caitlin Zaloom) 2014 Public Voices Fellowship, The Op-Ed Project, Columbia University 2014-PRESENT Fellow of the New York Institute for the Humanities 2013-2017 Administrative Internship Program grant, Graduate School of Arts and Sciences, Columbia University (to provide graduate students with alt-ac training via Public Books) 2011 Jerome Lawrence and Robert E. -

TIME IMAGERY H SHAKESPEARE's PLAYS and POEMS by Arthur T. Grant a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of English I

Time imagery in Shakespeare's plays and poems Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Grant, Arthur T. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 23/09/2021 12:08:25 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/566674 TIME IMAGERY H SHAKESPEARE'S PLAYS AND POEMS by Arthur T. Grant A Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Graduate College, University of Arizona 1952 Director of Thesis ( 9 7 9 / ' A 8- ■ TABLE OF COITEM'S m p f i R PAOE i. 33^DE©BTJCHOE , , , , , @ a , o o , , , & , , , , o @ , » * © I Fl23?POS© of0 "feL,© 000000ijL©SlS000:0 0 0 000I 0 , 0000B©T IL3sl3»^ 3.0IX Of 0t©3nH8 0000 0,00 0I 0 0 000 Advantages of the study , o « , , , o , , , © . = « . « o 1 gamzat ion © , ,. , ,. ,■ , o , o , © o o , , , o , o , 2 H o A REVIEW OF m m TREM3S H HiAGERY STUDY i 3 ly stfGd.3—es , , , , , , , o o o © o , , © © © © © o © © 3 The xntrosfective approach © © © © © © . © © © . © © © o 5 The Organic approach © © © © © © © © © © © © © » © © © ©, 9 The substantiation method © © , © © , © © © , © © © © © © 9 Summary © & © © © © © © © © © © © o © © © © © © © © o © © H , HI, A TMS AlID I#IP HOD S © © o © © © © © , © © © © © © © © © © © © © 12 Mature of the investigation . © © © © © © © © © © © © . © 12 Advantages of the investigation , , , © , © © © © © © © © 12 Disadvantages of the investigation © © © © © © © © © © © 14 Befinition of an image © © © © © © © © © © © , © © © © » 1% Method of gathering images , © © . -

Department of English [email protected] Rutgers University Leahprice.Org DATE of BIRTH: October 1970. Citizenship: USA. H

LEAH PRICE Department of English [email protected] Rutgers University leahprice.org DATE OF BIRTH: October 1970. Citizenship: USA. EMPLOYMENT: Henry Rutgers Distinguished Professor of English, Rutgers University (2019--) Founding director of Rutgers Initiative for the Book Professor of English, Harvard University. Francis Lee Higginson Professor, 2013-- Chair, History and Literature Program, 2007-12 Harvard College Professor (chair endowed for teaching excellence), 2006-12 Full Professor, 2003-- Assistant Professor, 2000-- Research Fellow in English Literature, Girton College, Cambridge, 1997-2000 EDUCATION: 1998 Ph.D. in Comparative Literature, Yale University. 1991 A.B. in Literature summa cum laude, Harvard University. GRANTS & PRIZES: 2017-18 NEH Public Scholar Fellowship. 2015, 2017 Elson Art-Making Grant, Harvard Faculty of Arts and Sciences. 2014 Robert Lowry Patten Prize for best book in 18th- or 19th-century British studies. 2013-14 Guggenheim Fellowship. 2013 Walter Channing Cabot Prize. 2013 Honorable mention, James Russell Lowell Prize for best book of literary criticism. 2010 Fellow, Columbia University Institute for Scholars (Paris). 2006-7 National Endowment for the Humanities Fellowship. 2006-7 Walter Jackson Bate Fellowship, Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study. 2002-3 Stanford Humanities Center Fellowship. 2000-02 Career Development Award (Harvard). 2000-3, 5-6, 8-10 Clarke-Cooke grant for research in the humanities (Harvard). 1994-97 Sterling Prize Fellowship (Yale). 1995-96 Andrew W. Mellon Dissertation Fellowship. 1995 Beinecke Library Fellowship. 1992-94 Mellon Fellowship in the Humanities. 1991-92 Bourse de recherches (Ministère des Affaires Etrangères, Paris). 113 1991-92 Augustus Clifford Tower Fellowship (Ecole Normale Supérieure). 1991 Fulbright Fellowship to Universidad de Buenos Aires (declined). -

The Way to Otranto: Gothic Elements

THE WAY TO OTRANTO: GOTHIC ELEMENTS IN EIGHTEENTH-CENTURY ENGLISH POETRY, 1717-1762 Vahe Saraoorian A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate School of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December 1970 ii ABSTRACT Although full-length studies have been written about the Gothic novel, no one has undertaken a similar study of poetry, which, if it may not be called "Gothic," surely contains Gothic elements. By examining Gothic elements in eighteenth-century poetry, we can trace through it the background to Horace Walpole's The Castle of Otranto, the first Gothic novel. The evolutionary aspect of the term "Gothic" itself in eighteenth-century criticism was pronounced, yet its various meanings were often related. To the early graveyard poets it was generally associated with the barbarous and uncouth, but to Walpole, writing in the second half of the century, the Gothic was also a source of inspiration and enlightenment. Nevertheless, the Gothic was most frequently associated with the supernatural. Gothic elements were used in the work of the leading eighteenth-century poets. Though an age not often thought remark able for its poetic expression, it was an age which clearly exploited the taste for Gothicism, Alexander Pope, Thomas Parnell, Edward Young, Robert Blair, Thomas and Joseph Warton, William Collins, Thomas Gray, and James Macpherson, the nine poets studied, all expressed notes of Gothicism in their poetry. Each poet con tributed to the rising taste for Gothicism. Alexander Pope, whose influence on Walpole was considerable, was the first poet of significance in the eighteenth century to write a "Gothic" poem. -

Caroline Spurgeon (1869–1942) and the Institutionalisation of English Studies As a Scholarly Discipline

PhiN-Beiheft | Supplement 4/2009 : 55 Juliette Dor (Liège, Belgium) Caroline Spurgeon (1869–1942) and the Institutionalisation of English Studies as a Scholarly Discipline Caroline Spurgeon (1869–1942) and the Institutionalisation of English Studies as a Scholarly Discipline Through a brief survey of the career, connections, and major activities of what was the first female university pr ofessor in London, this essay singles out Caroline Spurgeon's role in her country’s restructuring of English studies. She contributed to the renewal of academic English studies and she also secured the admission of British women to doctoral degrees at Oxford and Cambridge. The post- war crisis was a time of reconsideration of education (the elitism and male character of British educational system were especially attacked). The English committee, chaired by Sir Henry Newbolt, was, for instance, appointed to e nquire into the position of English (language and literature) in England and to advise how to promote its study. The Report emphasized the international scope of English, the value of their literature and the importance of education and culture for everybo dy. Caroline Spurgeon was involved in various committees debating the subject. She was receptive to the pressure to reject the German form of philology and also had a strong curiosity about the cultural dimension of literature. Through her teachings, writi ngs and activities inside her own department, she put her ideas of literary criticism into practice, and participated in the academic literary-critical renaissance of the 20s and early 30s. She was conjunctly an active militant in favour of women’s eligibi lity to any degree and struggled for their academic career. -

Classical Myth As Thematic Image in King Lear and Antony and Cleopatra

CLASSICAL MYTH AS THEMATIC IMAGE IN KING LEAR AND ANTONY AND CLEOPATRA By Freda Elizabeth Ward Submitted as an Honors Paper in the Department of English THE WOMAN'S COLLEGE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA GREENSBORO, NORTH CAROLINA 1952 PHLFACE Tnis paper is primarily a study of myth as it appears in King Lear and Antony and Cleopatra. A minor consideration is given to thematic imagery, its appearance in two early plays, and to mythology in general as it appears in Shaxespeare's plays. The investigation of Antony and Cleopatra has been conducted partly on the suggestions of others, especially Dr. Marc Friedlaender, but tne study of King Lear is my own research. In the two other plays that are briefly considered for their imagery, 1 have relied on the information collected by others, adding some instances of my own. TABLE OF CONTENTS Chapter Page I. SHAKESPEARIAN IMAGERY 1 II. SHAKESPEARE AND MYTHOLOGY 12 III. KING LEAR 19 IV. ANTONY AND CLEOPATRA 38 BIBLIOGRAPHY 58 Chapter I SHAKESPEARIAN IMAGERY An image is a linguistic device that presents by comparison or analogy with some other object a picture of an impression, emotion, or idea which comes to the poet. The image may be a word or group of words, and it may be a simile, a metaphor, or a word naving various levels of interpretation. The image is used to transmit more vividly to tne reader the idea of the poet. Because emotions and associations are aroused within the mind of the reader by the image, there is greater sensitivity to the idea of the poet. -

Benjamin Britten's Compositions for Children and Amateurs: Cloaking

i O ^ 3 3 1 Benjamin Britten’s compositions for children and amateurs: cloaking simplicity behind the veil of sophistication by Angie Flynn Thesis submitted to the National University of Ireland, Maynooth as part- fulfilment for the degree of Master of Arts in Historical Studies Head of Department: Professor Gerard Gillen Department of Music National University of Ireland Maynooth Co. Kildare Supervisor: Dr Mark Fitzgerald Department of Music National University of Ireland Maynooth Co. Kildare Naas, July 2006 \ 7 h N o r w i c h E a s t S u f f o l k s o u t h w o l d ; PEASENHA1X N o /\ t h YOXFORD SAXMUNDHAM GREAT flLC N H A M AL JOE BURGH PART OP j THE To I p n v ith & L o n d o n SUFFOLK COAST Contents Preface ii Acknowledgements v Introduction vii Benjamin Britten’s compositions for children and amateurs: cloaking simplicity behind the veil of sophistication Chapter 1 - 1 Chapter 2- 16 Chapter 3 - 30 Chapter 4 - 44 Conclusion 57 Appendix A 60 Appendix B 62 Appendix C 71 Appendix D 75 Bibliography 76 Abstract 80 Preface This thesis conforms to the house style of the Department of Music, National University of Ireland, Maynooth. As far as possible an adherence to The Oxford Dictionary of English has been made for spellings, where a choice is necessary. Any direct quotations from Britten’s letters or diaries (or, indeed, any correspondence relating to him) maintain his rather idiosyncratic and variable spelling style (e.g. ‘abit’) and his practice for underlining words, which would appear to be a habit he retained from childhood, and no attempt has thus been made to alter them. -

Appendix a the Leavises and Other Literatures

Appendix A The Leavises and Other Literatures Those who delight in discrediting or diminishing Leavis's achieve ment commonly cite his provinciality and bad manners for the coup de grace. But they usually give themselves away instead. To call Leavis provincial is patently absurd; and the charge of bad man ners is nine times out of ten highly debatable. Rene Wellek, a doughty combatant, calls Leavis 'provincial and insular' on account of three things: his 'concern with the Eng lish provincial moral tradition which he apparently fmds in Shakespeare, in Bunyan, in Jane Austen, in George Eliot, and D. H. Lawrence, all countryfolk'; his 'concern for his students, for the controversies of his university'; the fact that 'besides English and American, he seems to have no interest whatever in another literature' . 1 This is a caricature of Leavis, not the truth. The f1rst proposition neatly omits James and Conrad, to go no further; and as ifLeavis's interest in Shakespeare, and in promoting the great novelists, both American and English, as Shakespeare's successors, could be called provincial or insular! The second proposition trivialises the author of Educa#on and the University. (Ironically, there is an essay printed along with Wellek's in which Northrop Frye, with all the appearance of making new insights, discusses the university as a centre of spiritual authority in the modem world-Leavis's theme for more than twenty years before.) The third proposition, even if true, ignores a key premise with Leavis, that to say anything of weight the student of literature must become thoroughly at home in his own literature .first, before he branches out into other literatures. -

Jewish Stereotyping in English Fiction and Society, 1875-1914

AN OVERWHELMING QUESTION: JEWISH STEREOTYPING IN ENGLISH FICTION AND SOCIETY, 1875-1914 BY BRYM H. CHEYETTE, B.A., Hons., (Sheffield) THESIS PRESEt.ITED FOR THE DEGREE OF tXJCItR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF SHEFFIELD DEPARTMENTS OF ENGLISH LITERATURE AND ECCNOMIC AND SOCIAL HISTORY MAY 1986 "Streets that fo11ci like a tedious argument Of insidious intent To lead you to an overwhelming question. T.S. , Love Song 2 r4 Prufrock (1917) "But what was it? What did everybody mean about them?" Dorothy Richardson, The Tunnel (1920) 1 TABLE OF COt1TEtS Page Acknowledgements ii Summary 1]1 Note on editions used V Chapter 1 Jewish Stereotyping: A Theoretical Introduction 1 Chapter 2 Jewish Stereotyping and Modernity: Anthony Trollope and the Late 1870s 34 Chapter 3 Jewish Stereotyping and Social Darwinism: Ford Madox Ford and the Age of Evolutionism 73 Chapter 4 Jewish Stereotyping and Imperialism: John Buchan, Rudyard Kipling and the "Crisis of &npire" 96 Chapter 5 Jewish Stereotyping and Politics: Hilaire Belloc, G.K. Chesterton and Political Antisemitism 135 Chapter 6 Jewish Self-Stereotyping and Jewish &llancipation: Benjamin Farjeon, Amy Levy, Julia Frankau and the Modern Anglo-Jewish Novel 176 Chapter 7 Jewish Self-Stereotyping and Jewish Immigration: Israel Zangwill, Samuel Gordon and the Modern Anglo-Jewish Novel 220 Chapter 8 Jewish Stereotyping and Jewish Nationalism: George Eliot, Proto-Zionism and the Popular aiglish Novel 253 Chapter 9 Jewish Stereotyping and Socialism: H.G. Wells, George Bernard Shaw and the "Socialism of Fools" 292 Chapter 10 Jewish Stereotyping and Jewish Sexuality: George Du Maurier, Henry James and the Fiction of Desire 329 Chapter 11 Conclusion: Why the Jews? Jewish Stereotyping and the Christian Legacy 362 Bibliography 403 ii ACKWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the guidance of my supervisors, Professor Kenneth Graham and Dr.