Benjamin Britten's Compositions for Children and Amateurs: Cloaking

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Music-Making in a Joyous Sense”: Democratization, Modernity, and Community at Benjamin Britten's Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts

“Music-making in a Joyous Sense”: Democratization, Modernity, and Community at Benjamin Britten's Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts Daniel Hautzinger Candidate for Senior Honors in History Oberlin College Thesis Advisor: Annemarie Sammartino Spring 2016 Hautzinger ii Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Historiography and the Origin of the Festival 9 a. Historiography 9 b. The Origin of the Festival 14 3. The Democratization of Music 19 4. Technology, Modernity, and Their Dangers 31 5. The Festival as Community 39 6. Conclusion 53 7. Bibliography 57 a. Primary Sources 57 b. Secondary Sources 58 Hautzinger iii Acknowledgements This thesis would never have come together without the help and support of several people. First, endless gratitude to Annemarie Sammartino. Her incredible intellect, voracious curiosity, outstanding ability for drawing together disparate strands, and unceasing drive to learn more and know more have been an inspiring example over the past four years. This thesis owes much of its existence to her and her comments, recommendations, edits, and support. Thank you also to Ellen Wurtzel for guiding me through my first large-scale research paper in my third year at Oberlin, and for encouraging me to pursue honors. Shelley Lee has been an invaluable resource and advisor in the daunting process of putting together a fifty-some page research paper, while my fellow History honors candidates have been supportive, helpful in their advice, and great to commiserate with. Thank you to Steven Plank and everyone else who has listened to me discuss Britten and the Aldeburgh Festival and kindly offered suggestions. -

The Latest Newsletter. We Do Hope You Can Attend the AGM and the Holst Birthday Concert, Both in Cheltenham on Saturday 29Th September

SEPTEMBER 2018 Welcome to the latest newsletter. We do hope you can attend the AGM and the Holst Birthday Concert, both in Cheltenham on Saturday 29th September. AGM Sunday 23rd September at 2.30pm, Malvern Theatres, Malvern. Welcome to the latest newsletter. This month, we celebrate the Holst A Moorside Suite. 144th anniversary of the birth of Holst. The annual Holst Birthday Concert will take place in St Andrew’s URC, Sunday 23rd September at 3pm, St Mary Magdalene Church, th Montpellier Street, Cheltenham at 7.30pm on Saturday 29 Hucknall, Nottingham. Holst Choral Hymns from the Rig Veda. September. If you plan to be in Cheltenham that evening, why rd not make it a day’s visit by including the Society’s first AGM Sunday 23 September at 7.30pm, Wigmore Hall, London. which will be held at St Andrew’s URC that afternoon, at 4pm. Holst The Heart Worships. At the conclusion of the AGM, Angela Applegate will present a th PowerPoint illustrated celebration of Holst, entitled “Music, Saturday 29 September at 7.30pm, Ely Cathedral. Holst The Friendship and the Cotswold Hills: The Life of Gustav Holst”. Planets and The Cotswold Symphony. th We hope to finish events by 5.30pm, which should give a little Sunday 30 September at 3pm, Great Witley Church, time for a bite to eat, prior to the evening’s concert. Worcestershire. Holst The Moorside Suite. nd Please also note that we will be providing refreshments at the Tuesday 2 October at 7.30pm, St John’s Smith Square, AGM including hot drinks, biscuits and cake. -

Literature, Politics, and the University, 1932–19651

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by King's Research Portal King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1093/english/efw011 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Hutton, A. (2016). An English School for the Welfare State: Literature, Politics, and the University, 1932-1965. ENGLISH, 65(248), 3-34. https://doi.org/10.1093/english/efw011 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

English Translation of the German by Tom Hammond

Richard Strauss Susan Bullock Sally Burgess John Graham-Hall John Wegner Philharmonia Orchestra Sir Charles Mackerras CHAN 3157(2) (1864 –1949) © Lebrecht Music & Arts Library Photo Music © Lebrecht Richard Strauss Salome Opera in one act Libretto by the composer after Hedwig Lachmann’s German translation of Oscar Wilde’s play of the same name, English translation of the German by Tom Hammond Richard Strauss 3 Herod Antipas, Tetrarch of Judea John Graham-Hall tenor COMPACT DISC ONE Time Page Herodias, his wife Sally Burgess mezzo-soprano Salome, Herod’s stepdaughter Susan Bullock soprano Scene One Jokanaan (John the Baptist) John Wegner baritone 1 ‘How fair the royal Princess Salome looks tonight’ 2:43 [p. 94] Narraboth, Captain of the Guard Andrew Rees tenor Narraboth, Page, First Soldier, Second Soldier Herodias’s page Rebecca de Pont Davies mezzo-soprano 2 ‘After me shall come another’ 2:41 [p. 95] Jokanaan, Second Soldier, First Soldier, Cappadocian, Narraboth, Page First Jew Anton Rich tenor Second Jew Wynne Evans tenor Scene Two Third Jew Colin Judson tenor 3 ‘I will not stay there. I cannot stay there’ 2:09 [p. 96] Fourth Jew Alasdair Elliott tenor Salome, Page, Jokanaan Fifth Jew Jeremy White bass 4 ‘Who spoke then, who was that calling out?’ 3:51 [p. 96] First Nazarene Michael Druiett bass Salome, Second Soldier, Narraboth, Slave, First Soldier, Jokanaan, Page Second Nazarene Robert Parry tenor 5 ‘You will do this for me, Narraboth’ 3:21 [p. 98] First Soldier Graeme Broadbent bass Salome, Narraboth Second Soldier Alan Ewing bass Cappadocian Roger Begley bass Scene Three Slave Gerald Strainer tenor 6 ‘Where is he, he, whose sins are now without number?’ 5:07 [p. -

Delius Monument Dedicatedat the 23Rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn

The Delius SocieQ JOUrnAtT7 Summer/Autumn1992, Number 109 The Delius Sociefy Full Membershipand Institutionsf 15per year USA and CanadaUS$31 per year Africa,Australasia and Far East€18 President Eric FenbyOBE, Hon D Mus.Hon D Litt. Hon RAM. FRCM,Hon FTCL VicePresidents FelixAprahamian Hon RCO Roland Gibson MSc, PhD (FounderMember) MeredithDavies CBE, MA. B Mus. FRCM, Hon RAM Norman Del Mar CBE. Hon D Mus VernonHandley MA, FRCM, D Univ (Surrey) Sir CharlesMackerras CBE Chairman R B Meadows 5 WestbourneHouse. Mount ParkRoad. Harrow. Middlesex HAI 3JT Ti,easurer [to whom membershipenquiries should be directed] DerekCox Mercers,6 Mount Pleasant,Blockley, Glos. GL56 9BU Tel:(0386) 700175 Secretary@cting) JonathanMaddox 6 Town Farm,Wheathampstead, Herts AL4 8QL Tel: (058-283)3668 Editor StephenLloyd 85aFarley Hill. Luton. BedfordshireLul 5EG Iel: Luton (0582)20075 CONTENTS 'The others are just harpers . .': an afternoon with Sidonie Goossens by StephenLloyd.... Frederick Delius: Air and Dance.An historical note by Robert Threlfall.. BeatriceHarrison and Delius'sCello Music by Julian Lloyd Webber.... l0 The Delius Monument dedicatedat the 23rd Annual Festival by Thomas Hilton Gunn........ t4 Fennimoreancl Gerda:the New York premidre............ l1 -Opera A Village Romeo anrl Juliet: BBC2 Season' by Henry Gi1es......... .............18 Record Reviews Paris eIc.(BSO. Hickox) ......................2l Sea Drift etc. (WNOO. Mackerras),.......... ...........2l Violin Concerto etc.(Little. WNOOO. Mackerras)................................22 Violin Concerto etc.(Pougnet. RPO. Beecham) ................23 Hassan,Sea Drift etc. (RPO. Beecham) . .-................25 THE HARRISON SISTERS Works by Delius and others..............26 A Mu.s:;r1/'Li.fe at the Brighton Festival ..............27 South-WestBranch Meetinss.. ........30 MicllanclsBranch Dinner..... ............3l Obittrary:Sir Charles Groves .........32 News Round-Up ...............33 Correspondence....... -

Britten Spring Symphony Welcome Ode • Psalm 150

BRITTEN SPRING SYMPHONY WELCOME ODE • PSALM 150 Elizabeth Gale soprano London Symphony Chorus Alfreda Hodgson contralto Martyn Hill tenor London Symphony Orchestra Southend Boys’ Choir Richard Hickox Greg Barrett Richard Hickox (1948 – 2008) Benjamin Britten (1913 – 1976) Spring Symphony, Op. 44* 44:44 For Soprano, Alto and Tenor solos, Mixed Chorus, Boys’ Choir and Orchestra Part I 1 Introduction. Lento, senza rigore 10:03 2 The Merry Cuckoo. Vivace 1:57 3 Spring, the Sweet Spring. Allegro con slancio 1:47 4 The Driving Boy. Allegro molto 1:58 5 The Morning Star. Molto moderato ma giocoso 3:07 Part II 6 Welcome Maids of Honour. Allegretto rubato 2:38 7 Waters Above. Molto moderato e tranquillo 2:23 8 Out on the Lawn I lie in Bed. Adagio molto tranquillo 6:37 Part III 9 When will my May come. Allegro impetuoso 2:25 10 Fair and Fair. Allegretto grazioso 2:13 11 Sound the Flute. Allegretto molto mosso 1:24 Part IV 12 Finale. Moderato alla valse – Allegro pesante 7:56 3 Welcome Ode, Op. 95† 8:16 13 1 March. Broad and rhythmic (Maestoso) 1:52 14 2 Jig. Quick 1:20 15 3 Roundel. Slower 2:38 16 4 Modulation 0:39 17 5 Canon. Moving on 1:46 18 Psalm 150, Op. 67‡ 5:31 Kurt-Hans Goedicke, LSO timpani Lively March – Lightly – Very lively TT 58:48 4 Elizabeth Gale soprano* Alfreda Hodgson contralto* Martyn Hill tenor* The Southend Boys’ Choir* Michael Crabb director Senior Choirs of the City of London School for Girls† Maggie Donnelly director Senior Choirs of the City of London School† Anthony Gould director Junior Choirs of the City of London School -

Copland As Mentor to Britten, 1939-1942

'You absolutely owe it to England to stay here': Copland as mentor to Britten, 1939-1942 Suzanne Robinson Few details of the circumstances of Benjamin Copland to visit him for the weekend at his home in a Britten's stay in America in the years 1939-42 were converted mill in Snape. On this occasion they familiar- known before the publication in 1991of Britten's letters ised one another with their music; Copland played his and, in 1992, of a biography by Humphrey Carpenter. school opera, The Second Hurricane, singing all the parts And with the exception of a short article on Aaron himself, while Britten performed the first version of his Copland and Britten in an Aldeburgh Festival Programme Piano ~oncerto.~Being July, and England, at the first ~ook,llittle attention has been paid to the significance sign of sunshine the locals escorted their visitor to one of Britten's exposure to Copland's music, which Britten of Suffolk's pebbled beaches (which Copland described regarded as the best America had to offer. More than 20 as a 'shingle'). Copland realised that perhaps he was letters survive between 'Benjie' and 'my dearest Aaron', more accustomed to the effects of the sun, when Ibefore the majority of them belonging to the war years when long it became clear that the assembled group was in Copland was resident in New York and Britten was, for danger of "roasting". When I politely pointed out the the most part, nearby in Long ~sland.~Britten fre- obvious result to be expected from lying unprotected quently referred to Copland as his 'very dear friend', on the beach, I was told: "But we see the sun so and even 'Father' (Copland was the senior of the two rarely"'? When he returned to America, copland wrote by 13 years). -

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company Sally Elizabeth Drew A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Music This work was supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council September 2018 1 2 Abstract This thesis examines the working culture of the Decca Record Company, and how group interaction and individual agency have made an impact on the production of music recordings. Founded in London in 1929, Decca built a global reputation as a pioneer of sound recording with access to the world’s leading musicians. With its roots in manufacturing and experimental wartime engineering, the company developed a peerless classical music catalogue that showcased technological innovation alongside artistic accomplishment. This investigation focuses specifically on the contribution of the recording producer at Decca in creating this legacy, as can be illustrated by the career of Christopher Raeburn, the company’s most prolific producer and specialist in opera and vocal repertoire. It is the first study to examine Raeburn’s archive, and is supported with unpublished memoirs, private papers and recorded interviews with colleagues, collaborators and artists. Using these sources, the thesis considers the history and functions of the staff producer within Decca’s wider operational structure in parallel with the personal aspirations of the individual in exerting control, choice and authority on the process and product of recording. Having been recruited to Decca by John Culshaw in 1957, Raeburn’s fifty-year career spanned seminal moments of the company’s artistic and commercial lifecycle: from assisting in exploiting the dramatic potential of stereo technology in Culshaw’s Ring during the 1960s to his serving as audio producer for the 1990 The Three Tenors Concert international phenomenon. -

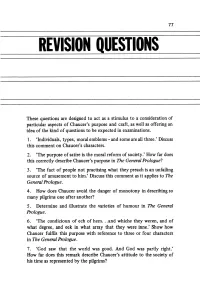

Revision Questions

77 REVISION QUESTIONS These questions are designed to act as a stimulus to a consideration of particular aspects of Chaucer's purpose and craft, as well as offering an idea of the kind of questions to be expected in examinations. 1. 'Individuals, types, moral emblems - and some are all three.' Discuss this comment on Chaucer's characters. 2. 'The purpose ofsatire is the moral reform ofsociety.' How far does this correctly describe Chaucer's purpose in The General Prologue? 3. 'The fact of people not practising what they preach is an unfailing source of amusement to him.' Discuss this comment as it applies to The General Prologue. 4. How does Chaucer avoid the danger of monotony in describing so many pilgrims one after another? 5. Determine and illustrate the varieties of humour in The General Prologue. 6. 'The condicioun of ech of hem ...and whiche they weren, and of what degree, and eek in what array that they were inne.' Show how Chaucer fulfils this purpose with reference to three or four characters in The General Prologue. 7. 'God saw that the world was good. And God was partly right.' How far does this remark describe Chaucer's attitude to the society of his time as represented by the pilgrims? 79 FURTHER READING Long book lists can be both daunting and useless, if a student cannot decide what will be of immediate interest to him. For this reason this bibliography has been kept very short. Its purpose is merely to point in one or two useful directions; further signposts are plentiful as soon as any of these books are examined. -

Britten Connections a Guide for Performers and Programmers

Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Britten –Pears Foundation Telephone 01728 451 700 The Red House, Golf Lane, [email protected] Aldeburgh, Suffolk, IP15 5PZ www.brittenpears.org Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Contents The twentieth century’s Programming tips for 03 consummate musician 07 13 selected Britten works Britten connected 20 26 Timeline CD sampler tracks The Britten-Pears Foundation is grateful to Orchestra, Naxos, Nimbus Records, NMC the following for permission to use the Recordings, Onyx Classics. EMI recordings recordings featured on the CD sampler: BBC, are licensed courtesy of EMI Classics, Decca Classics, EMI Classics, Hyperion Records, www.emiclassics.com For full track details, 28 Lammas Records, London Philharmonic and all label websites, see pages 26-27. Index of featured works Front cover : Britten in 1938. Photo: Howard Coster © National Portrait Gallery, London. Above: Britten in his composition studio at The Red House, c1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton . 29 Further information Opposite left : Conducting a rehearsal, early 1950s. Opposite right : Demonstrating how to make 'slung mugs' sound like raindrops for Noye's Fludde , 1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton. Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers 03 The twentieth century's consummate musician In his tweed jackets and woollen ties, and When asked as a boy what he planned to be He had, of course, a great guide and mentor. with his plummy accent, country houses and when he grew up, Britten confidently The English composer Frank Bridge began royal connections, Benjamin Britten looked replied: ‘A composer.’ ‘But what else ?’ was the teaching composition to the teenage Britten every inch the English gentleman. -

Missa Brevis

Jacob de Haan Missa Brevis Partiture per coro misto Solo per uso personale 2 Ⓡ Ⓡ Soli Deo Hon Et Gl ia 3 Missa Brevis Indice dei contenuti Kyrie .............................................. .............. 4 Gloria............................................. ............... 6 Credo.............................................. .............. 11 Sanctus ............................................ .............. 18 Benedictus......................................... ................ 20 Agnus Dei .......................................... ............... 24 4 Missa Brevis Kyrie Coro Misto Jacob de Haan ø = 80 Soprano 11 2 2 Ky ri e e lei son, Ky ri e e lei son, f f Alto 11 2 2 11 Tenore 2 8 2 Kyf ri e e lei son, Kyf ri e e lei son, 11 Basso 2 2 19 S 3 Ky ri e e lei son, Ky ri e e lei son, 2 f f A 3 2 T 3 8 2 Kyf ri e e lei son, Kyf ri e e lei son, B 3 2 28 S 3 2 3 2 3 2 3 2 Ky ri e e 2 lei son, 2 Ky ri e e 2 lei son. 2Christe e 2 lei son, 2 ff f p A 3 2 3 2 3 2 3 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 T 3 2 3 2 3 2 3 8 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 Kyff ri e e lei son, Kyf ri e e lei son. Chrip ste e lei son, B 3 2 3 2 3 2 3 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 Coro Misto 5 34 S 3 2 3 2 2 Christe e 2 lei son, e lei son, 2 Chri ste Chri ste 2Christe e A ff ff ff 3 2 3 2 2 2 2 2 T 3 2 3 2 8 2 2 2 2 Christe e lei son, e lei son, Chriff ste Chriff ste Chriff ste e B 3 2 3 2 2 2 2 2 41 S 2 2 3 2 3 lei son. -

BENJAMIN BRITTEN a Ceremony of Carols IRELAND | BRIDGE | HOLST

BENJAMIN BRITTEN A Ceremony of Carols IRELAND | BRIDGE | HOLST Choir of Clare College, Cambridge Graham Ross FRANZ LISZT A Ceremony of Carols BENJAMIN BRITTEN (1913-1976) ANONYMOUS, arr. BENJAMIN BRITTEN 1 | Venite exultemus Domino 4’11 12 | The Holly and the Ivy 3’36 for mixed choir and organ (1961) traditional folksong, arranged for mixed choir a cappella (1957) 2 | Te Deum in C 7’40 for mixed choir and organ (1934) BENJAMIN BRITTEN 3 | Jubilate Deo in C 2’30 13 | Sweet was the song the Virgin sung 2’45 for mixed choir and organ (1961) from Christ’s Nativity for soprano and mixed choir a cappella (1931) 4 | Deus in adjutorium meum intende 4’37 from This Way to the Tomb for mixed choir a cappella (1944-45) A Ceremony of Carols op. 28 (1942, rev. 1943) version for mixed choir and harp arranged by JULIUS HARRISON (1885-1963) 5 | A Hymn to the Virgin 3’23 for solo SATB and mixed choir a cappella (1930, rev. 1934) 14 | 1. Procession 1’18 6 | A Hymn of St Columba 2’01 15 | 2. Wolcum Yole! 1’21 for mixed choir and organ (1962) 16 | 3. There is no rose 2’27 7 | Hymn to St Peter op. 56a 5’57 17 | 4a. That yongë child 1’50 for mixed choir and organ (1955) 18 | 4b. Balulalow 1’18 19 | 5. As dew in Aprille 0’56 JOHN IRELAND (1879-1962) 20 | 6. This little babe 1’24 8 | The Holy Boy 2’50 version for mixed choir a cappella (1941) 21 | 7.