Literature, Politics, and the University, 1932–19651

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Study of Feminine and Feminist Subjectivity in the Poetry of Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton, Margaret Atwood and Adrienne Rich, 1950-1980 Little, Philippa Susan

Images of Self: A Study of Feminine and Feminist Subjectivity in the Poetry of Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton, Margaret Atwood and Adrienne Rich, 1950-1980 Little, Philippa Susan The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author For additional information about this publication click this link. http://qmro.qmul.ac.uk/jspui/handle/123456789/1501 Information about this research object was correct at the time of download; we occasionally make corrections to records, please therefore check the published record when citing. For more information contact [email protected] Images of Self: A Study of Feminine and Feminist Subjectivity in the Poetry of Sylvia Plath, Anne Sexton, Margaret Atwood and Adrienne Rich, 1950-1980. A thesis supervised by Dr. Isobel Grundy and submitted at Queen Mary and Westfield College, in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Ph. D. by Philippa Susan Little June 1990. The thesis explores the poetry (and some prose) of Plath, Sexton, Atwood and Rich in terms of the changing constructions of self-image predicated upon the female role between approx. 1950-1980.1 am particularly concerned with the question of how the discourses of femininity and feminism contribute to the scope of the images of the self which are presented. The period was chosen because it involved significant upheaval and change in terms of women's role and gender identity. The four poets' work spans this period of change and appears to some extent generally characteristic of its social, political and cultural contexts in America, Britain and Canada. -

The Pelican Record Corpus Christi College Vol

The Pelican Record Corpus Christi College Vol. LV December 2019 The Pelican Record The President’s Report 4 Features 10 Ruskin’s Vision by David Russell 10 A Brief History of Women’s Arrival at Corpus by Harriet Patrick 18 Hugh Oldham: “Principal Benefactor of This College” by Thomas Charles-Edwards 26 The Building Accounts of Corpus Christi College, Oxford, 1517–18 by Barry Collett 34 The Crew That Made Corpus Head of the River by Sarah Salter 40 Richard Fox, Bishop of Durham by Michael Stansfield 47 Book Reviews 52 The Renaissance Reform of the Book and Britain: The English Quattrocento by David Rundle; reviewed by Rod Thomson 52 Anglican Women Novelists: From Charlotte Brontë to P.D. James, edited by Judith Maltby and Alison Shell; reviewed by Emily Rutherford 53 In Search of Isaiah Berlin: A Literary Adventure by Henry Hardy; reviewed by Johnny Lyons 55 News of Corpuscles 59 News of Old Members 59 An Older Torpid by Andrew Fowler 61 Rediscovering Horace by Arthur Sanderson 62 Under Milk Wood in Valletta: A Touch of Corpus in Malta by Richard Carwardine 63 Deaths 66 Obituaries: Al Alvarez, Michael Harlock, Nicholas Horsfall, George Richardson, Gregory Wilsdon, Hal Wilson 67-77 The Record 78 The Chaplain’s Report 78 The Library 80 Acquisitions and Gifts to the Library 84 The College Archives 90 The Junior Common Room 92 The Middle Common Room 94 Expanding Horizons Scholarships 96 Sharpston Travel Grant Report by Francesca Parkes 100 The Chapel Choir 104 Clubs and Societies 110 The Fellows 122 Scholarships and Prizes 2018–2019 134 Graduate -

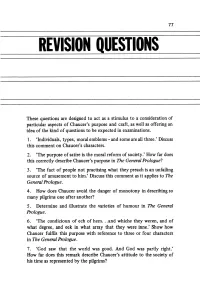

Revision Questions

77 REVISION QUESTIONS These questions are designed to act as a stimulus to a consideration of particular aspects of Chaucer's purpose and craft, as well as offering an idea of the kind of questions to be expected in examinations. 1. 'Individuals, types, moral emblems - and some are all three.' Discuss this comment on Chaucer's characters. 2. 'The purpose ofsatire is the moral reform ofsociety.' How far does this correctly describe Chaucer's purpose in The General Prologue? 3. 'The fact of people not practising what they preach is an unfailing source of amusement to him.' Discuss this comment as it applies to The General Prologue. 4. How does Chaucer avoid the danger of monotony in describing so many pilgrims one after another? 5. Determine and illustrate the varieties of humour in The General Prologue. 6. 'The condicioun of ech of hem ...and whiche they weren, and of what degree, and eek in what array that they were inne.' Show how Chaucer fulfils this purpose with reference to three or four characters in The General Prologue. 7. 'God saw that the world was good. And God was partly right.' How far does this remark describe Chaucer's attitude to the society of his time as represented by the pilgrims? 79 FURTHER READING Long book lists can be both daunting and useless, if a student cannot decide what will be of immediate interest to him. For this reason this bibliography has been kept very short. Its purpose is merely to point in one or two useful directions; further signposts are plentiful as soon as any of these books are examined. -

Modernist Mediums of Transcendence in Sylvia Plath's Poetry and Prose

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 2003 Love, Violence, and Creation: Modernist Mediums of Transcendence in Sylvia Plath's Poetry and Prose Autumn Williams Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Williams, Autumn, "Love, Violence, and Creation: Modernist Mediums of Transcendence in Sylvia Plath's Poetry and Prose" (2003). Masters Theses. 1395. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/1395 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THESIS REPRODUCTION CERTIFICATE TO: Graduate Degree Candidates (who have written formal theses) SUBJECT: Permission to Reproduce Theses The University Library is receiving a number of request from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow these to be copied. PLEASE SIGN ONE OF THE FOLLOWING STATEMENTS: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. Date I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University NOT allow my thesis to be reproduced because: Author's Signature Date This form must be submitted in duplicate. -

Myths, Legends, and Apparitional Lesbians: Amy Lowell's Haunting Modernism

This is a repository copy of Myths, Legends, and Apparitional Lesbians: Amy Lowell's Haunting Modernism. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/122951/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Roche, H (2018) Myths, Legends, and Apparitional Lesbians: Amy Lowell's Haunting Modernism. Modernist Cultures, 13 (4). pp. 568-589. ISSN 2041-1022 https://doi.org/10.3366/mod.2018.0230 This article is protected by copyright. All rights reserved. This is an author produced version of a paper accepted for publication in Modernist Cultures, published by the Edinburgh University Press, at: http://www.euppublishing.com/loi/mod. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Myths, Legends, and Apparitional Lesbians: Amy Lowell’s Haunting Modernism Dr Hannah Roche Email: [email protected] Affiliation: University of Leeds 1 Abstract By the end of the twentieth century, Amy Lowell’s poetry had been all but erased from modernism, with her name resurfacing only in relation to her dealings with Ezra Pound, her distant kinship with Robert Lowell, or her correspondence with D. -

Two Contemporary Poets and the Ted Hughes Bestiary

WESTON | THE TED HUGHES SOCIETY JOURNAL VII .1 Two Contemporary Poets and the Ted Hughes Bestiary Daniel Weston Who was the first poet to write about birds having observed them with the aid of binoculars? The question is posed by naturalist Tim Dee in his foreword to The Poetry of Birds (2009), the anthology he co-edited with Simon Armitage. His tentative offering in response is that Edward Thomas ‘may have slung a rudimentary pair around his neck’, but with some more certainty, ‘it is possible to detect binocular- assisted poetry in some of Ted Hughes’s work’.1 This speculation, verified or not, is useful because it is based on noticing the observational qualities that can be discerned clearly in Hughes’s animal poems. It is this same documentary closeness to the animals observed that Dee and Armitage value most highly in the contemporary poems they select for inclusion in their trans-historical anthology. The best bird poems written recently, Dee notes in praise of work by Michael Longley, Kathleen Jamie, and Peter Reading, are ‘open-eyed meetings that are crammed with ornithological acuity and capture the direct experience of looking at birds today, giving us a comparable quickening to that which leaps up around any encounter we have with the real things’.2 In this alignment of what both Hughes and contemporary poets bring to the fore, we can begin to see one of the chief ways in which Hughes’s legacy is felt in poetry today. Of contemporary A-list poets, Armitage is perhaps the most obviously influenced by Ted Hughes’s legacy. -

Literary Contexts

Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42555-1 — Ted Hughes in Context Edited by Terry Gifford Excerpt More Information part i Literary Contexts © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42555-1 — Ted Hughes in Context Edited by Terry Gifford Excerpt More Information © in this web service Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 978-1-108-42555-1 — Ted Hughes in Context Edited by Terry Gifford Excerpt More Information chapter 1 Hughes and His Contemporaries Jonathan Locke Hart The complexity of Hughes’s early poetic contexts has been occluded by a somewhat polarised critical sense of the 1950s in which the work of the Movement poets, frequently represented by Philip Larkin, is seen to have been challenged by the poets of Al Alvarez’s anthology, The New Poetry (1962). Alvarez’s introductory essay, subtitled, ‘Beyond the Gentility Principle’, appeared to offer Hughes’s poetry as an antidote to Larkin’s work, which he nevertheless also included in The New Poetry. John Goodby argues that actually Hughes ‘did not so much “revolt against” the Movement so much as precede it, and continue regardless of it in extending English poetry’s radical-dissident strain’.1 Goodby’s case is based upon the early influences upon Hughes’s poetry of D. H. Lawrence,2 Robert Graves3 and Dylan Thomas. In the latter case, for example, Goodby argues that ‘Hughes’s quarrying of Thomas went beyond verbal resemblances to shared intellectual co-ordinates that include the work of Schopenhauer and the Whitehead-influenced “process poetic” forged by Thomas in 1933–34’.4 Ted Hughes’s supervisor at Cambridge, Doris Wheatley, ‘confessed that she had learned more from him about Dylan Thomas than he had learned from her about John Donne’.5 In a literal sense, the contemporaries of Ted Hughes are those who lived at the same time as Hughes – that is, from 1930 to 1998. -

1. Philip Larkin

Notes References to material held in the Philip Larkin Archive lodged in the Brynmor Jones Library, University of Hull (BJL), are given as file numbers preceded by 'DPL'. 1. PHILIP LARKIN 1. Harry Chambers, 'Meeting Philip Larkin', in Larkin at Sixty, ed. Anthony Thwaite (London: Faber and Faber, 1982) p. 62. 2. John Haffenden, Viewpoints: Poets in Conversation (London, Faber and Faber, 1981) p. 127. 3. Christopher Ricks, Beckett's Dying Words (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993). 4. D. J. Enright, 'Down Cemetery Road: the Poetry of Philip Larkin', in Conspirators and Poets (London: Chatto & Windus, 1966) p. 142. 5. Hugo Roeffaers, 'Schriven tegen de Verbeelding', Streven, vol. 47 (December 1979) pp. 209-22. 6. Andrew Motion, Philip Larkin: A Writer's Life (London: Faber and Faber, 1993). 7. Philip Larkin, Required Writing (London: Faber and Faber, 1983) p. 48. 8. See Selected Letters of Philip Larkin 1940-1985, ed. Anthony Thwaite (London: Faber and Faber, 1992) pp. 648-9. 9. DPL 2 (in BJL). 10. DPL 5 (in BJL). 11. Kingsley Amis, Memoirs (London: Hutchinson, 1991) p. 52. 12. Philip Larkin, Introduction to Jill (London: The Fortune Press, 1946; rev. edn. Faber and Faber, 1975) p. 12. 13. Donald Davie, Thomas Hardy and British Poetry (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1973) p. 64. 14. Required Writing, p. 297. 15. Blake Morrison, 'In the grip of darkness', The Times Literary Supplement, 14-20 October 1988, p. 1152. 16. Lisa Jardine, 'Saxon violence', Guardian, 8 December 1992. 17. Bryan Appleyard, 'The dreary laureate of our provincialism', Independent, 18 March 1993. 18. Ian Hamilton, 'Self's the man', The Times Literary Supplement, 2 April 1993, p. -

The Writer's Voice, 2006, Al Alvarez, 0747579318, 9780747579311, Bloomsbury, 2006

The Writer's Voice, 2006, Al Alvarez, 0747579318, 9780747579311, Bloomsbury, 2006 DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1c2tMMx http://goo.gl/RJmy2 http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?search=The+Writer%27s+Voice What makes good writing good? In his brilliant new book, Al Alvarez argues that it is the development of the voice - voice as distinct from style - that makes a writer great. A poet as well as a critic, Al Alvarez approaches his subject both as an informed observer and an insider. Here are - among others - Sylvia Plath, John Donne, Jean Rhys, Shakespeare, T. S. Eliot, Coleridge and W. B. Yeats, dissected with clarity, depth and a profound understanding of the mechanics of writing. Like the best literary criticism, The Writer's Voicemakes writing come vividly alive. Written with passion and insight, it is the ideal gift for anyone who loves to read. DOWNLOAD http://fb.me/2MzkBobh7 http://www.fishpond.co.nz/Books/The-Writers-Voice http://bit.ly/1w2AA7k Risky Business People, Pastimes, Poker and Books, Al Alvarez, Jan 21, 2008, Language Arts & Disciplines, 409 pages. Al Alvarez's writing career has come in many guises. One of the most influential post-war critics, he has written profoundly and eloquently about writers and their craft for. Sylvia Plath , Eileen M. Aird, 1973, Literary Criticism, 114 pages. Where Did It All Go Right? , Al Alvarez, Mar 1, 2002, Authors, English, 352 pages. This is the autobiography of poet, critic, novelist, sportsman and poker player, Al Alvarez. Although his family had been settled in London for more than two centuries, being. -

The Ted Hughes Society Journal

The Ted Hughes Society Journal Volume VIII Issue 1 The Ted Hughes Society Journal Co-Editors Dr James Robinson Durham University Dr Mark Wormald Pembroke College Cambridge Reviews Editor Prof. Terry Gifford Bath Spa University Editorial Assistant Dr Mike Sweeting Editorial Board Prof. Terry Gifford Bath Spa University Dr Yvonne Reddick University of Central Lancashire Prof. Neil Roberts University of Sheffield Dr Carrie Smith Cardiff University Production Manager Dr David Troupes Published by the Ted Hughes Society. All matters pertaining to the Ted Hughes Society Journal should be sent to: [email protected] You can contact the Ted Hughes Society via email at: [email protected] Questions about joining the Society should be sent to: [email protected] thetedhughessociety.org This Journal is copyright of the Ted Hughes Society but copyright of the articles is the property of their authors. Written consent should be requested from the copyright holder before reproducing content for personal and/or educational use; requests for permission should be addressed to the Editor. Commercial copying is prohibited without written consent. 2 Contents Editorial ......................................................................................................................4 Mark Wormald List of abbreviations of works by Ted Hughes .......................................................... 7 The Wound that Bled Lupercal: Ted Hughes in Massachusetts .............................. 8 David Troupes ‘Right to -

Wright, Natalie Francesca.Pdf

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Pragmatic Criticism: Women and Femininity in the Inauguration of Academic English Studies in the U.K., 1900-1950 Natalie Francesca Wright Ph.D. University of Sussex August 2020 2 I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature: ……………………………………… 3 University of Sussex Natalie Francesca Wright Doctorate of Philosophy Pragmatic Criticism: Women and Femininity in the Inauguration of Academic English Studies in the U.K., 1900-1950 This project looks at how gender operates in literary-critical values during the formation of U.K. English departments in the early twentieth century through the lives and work of three pioneering women scholars: Edith Morley, Caroline Spurgeon, and Q. D. Leavis. It argues that academic literary studies inculcated masculine critical rhetoric into the discipline, revolving around the conceptual pillars of stoicism, seriousness, and hard work, and that this rhetoric had a material impact on early women scholars. -

Representations of Space in the Poetry of Robert Lowell, Sylvia Plath, and Anne Sexton

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Loughborough University Institutional Repository ‘My landscape is a hand with no lines’: Representations of Space in the Poetry of Robert Lowell, Sylvia Plath, and Anne Sexton A Doctoral Thesis by Mohammed Fattah Rashid Al-Obaidi Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the award of Doctor of Philosophy of Loughborough University Supervised by Dr. Brian Jarvis Dr. Deirdre O’Byrne September 2017 © Mohammed Al-Obaidi Abstract This thesis is the first study using contemporary spatial theory, including cultural geography and its precursors, to examine and compare representations of space in the poetry of three mid- twentieth–century American poets: Robert Lowell, Sylvia Plath, and Anne Sexton. Because of the autobiographical content often foregrounded in their work, these poets have been labelled ‘Confessional.’ Previous criticism has focused primarily on the ways in which they narrate (or draw on) their personal lives, treating accompanying descriptions of their surroundings primarily as backdrops. However, these poets frequently manifest their affective states by using the pathetic fallacy within structures of metaphor that form a textual ‘mapping’ of the physical space they describe. This mapping can be temporal as well as spatial; the specific spaces ‘mapped’ in the poem’s present are often linked to memories of earlier life or family. These spaces include psychiatric, general, and penal institutions, parks and gardens, nature (especially coastal settings), and the home (almost always a place of tension or conflict). Each poet addresses these broad types of space differently according to their evolving subjective relationship to them.