Appendix a the Leavises and Other Literatures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Literature, Politics, and the University, 1932–19651

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by King's Research Portal King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1093/english/efw011 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Hutton, A. (2016). An English School for the Welfare State: Literature, Politics, and the University, 1932-1965. ENGLISH, 65(248), 3-34. https://doi.org/10.1093/english/efw011 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

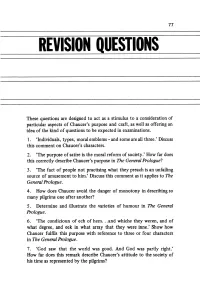

Revision Questions

77 REVISION QUESTIONS These questions are designed to act as a stimulus to a consideration of particular aspects of Chaucer's purpose and craft, as well as offering an idea of the kind of questions to be expected in examinations. 1. 'Individuals, types, moral emblems - and some are all three.' Discuss this comment on Chaucer's characters. 2. 'The purpose ofsatire is the moral reform ofsociety.' How far does this correctly describe Chaucer's purpose in The General Prologue? 3. 'The fact of people not practising what they preach is an unfailing source of amusement to him.' Discuss this comment as it applies to The General Prologue. 4. How does Chaucer avoid the danger of monotony in describing so many pilgrims one after another? 5. Determine and illustrate the varieties of humour in The General Prologue. 6. 'The condicioun of ech of hem ...and whiche they weren, and of what degree, and eek in what array that they were inne.' Show how Chaucer fulfils this purpose with reference to three or four characters in The General Prologue. 7. 'God saw that the world was good. And God was partly right.' How far does this remark describe Chaucer's attitude to the society of his time as represented by the pilgrims? 79 FURTHER READING Long book lists can be both daunting and useless, if a student cannot decide what will be of immediate interest to him. For this reason this bibliography has been kept very short. Its purpose is merely to point in one or two useful directions; further signposts are plentiful as soon as any of these books are examined. -

Wright, Natalie Francesca.Pdf

A University of Sussex PhD thesis Available online via Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/ This thesis is protected by copyright which belongs to the author. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the Author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the Author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Please visit Sussex Research Online for more information and further details Pragmatic Criticism: Women and Femininity in the Inauguration of Academic English Studies in the U.K., 1900-1950 Natalie Francesca Wright Ph.D. University of Sussex August 2020 2 I hereby declare that this thesis has not been and will not be, submitted in whole or in part to another University for the award of any other degree. Signature: ……………………………………… 3 University of Sussex Natalie Francesca Wright Doctorate of Philosophy Pragmatic Criticism: Women and Femininity in the Inauguration of Academic English Studies in the U.K., 1900-1950 This project looks at how gender operates in literary-critical values during the formation of U.K. English departments in the early twentieth century through the lives and work of three pioneering women scholars: Edith Morley, Caroline Spurgeon, and Q. D. Leavis. It argues that academic literary studies inculcated masculine critical rhetoric into the discipline, revolving around the conceptual pillars of stoicism, seriousness, and hard work, and that this rhetoric had a material impact on early women scholars. -

Benjamin Britten's Compositions for Children and Amateurs: Cloaking

i O ^ 3 3 1 Benjamin Britten’s compositions for children and amateurs: cloaking simplicity behind the veil of sophistication by Angie Flynn Thesis submitted to the National University of Ireland, Maynooth as part- fulfilment for the degree of Master of Arts in Historical Studies Head of Department: Professor Gerard Gillen Department of Music National University of Ireland Maynooth Co. Kildare Supervisor: Dr Mark Fitzgerald Department of Music National University of Ireland Maynooth Co. Kildare Naas, July 2006 \ 7 h N o r w i c h E a s t S u f f o l k s o u t h w o l d ; PEASENHA1X N o /\ t h YOXFORD SAXMUNDHAM GREAT flLC N H A M AL JOE BURGH PART OP j THE To I p n v ith & L o n d o n SUFFOLK COAST Contents Preface ii Acknowledgements v Introduction vii Benjamin Britten’s compositions for children and amateurs: cloaking simplicity behind the veil of sophistication Chapter 1 - 1 Chapter 2- 16 Chapter 3 - 30 Chapter 4 - 44 Conclusion 57 Appendix A 60 Appendix B 62 Appendix C 71 Appendix D 75 Bibliography 76 Abstract 80 Preface This thesis conforms to the house style of the Department of Music, National University of Ireland, Maynooth. As far as possible an adherence to The Oxford Dictionary of English has been made for spellings, where a choice is necessary. Any direct quotations from Britten’s letters or diaries (or, indeed, any correspondence relating to him) maintain his rather idiosyncratic and variable spelling style (e.g. ‘abit’) and his practice for underlining words, which would appear to be a habit he retained from childhood, and no attempt has thus been made to alter them. -

Jewish Stereotyping in English Fiction and Society, 1875-1914

AN OVERWHELMING QUESTION: JEWISH STEREOTYPING IN ENGLISH FICTION AND SOCIETY, 1875-1914 BY BRYM H. CHEYETTE, B.A., Hons., (Sheffield) THESIS PRESEt.ITED FOR THE DEGREE OF tXJCItR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF SHEFFIELD DEPARTMENTS OF ENGLISH LITERATURE AND ECCNOMIC AND SOCIAL HISTORY MAY 1986 "Streets that fo11ci like a tedious argument Of insidious intent To lead you to an overwhelming question. T.S. , Love Song 2 r4 Prufrock (1917) "But what was it? What did everybody mean about them?" Dorothy Richardson, The Tunnel (1920) 1 TABLE OF COt1TEtS Page Acknowledgements ii Summary 1]1 Note on editions used V Chapter 1 Jewish Stereotyping: A Theoretical Introduction 1 Chapter 2 Jewish Stereotyping and Modernity: Anthony Trollope and the Late 1870s 34 Chapter 3 Jewish Stereotyping and Social Darwinism: Ford Madox Ford and the Age of Evolutionism 73 Chapter 4 Jewish Stereotyping and Imperialism: John Buchan, Rudyard Kipling and the "Crisis of &npire" 96 Chapter 5 Jewish Stereotyping and Politics: Hilaire Belloc, G.K. Chesterton and Political Antisemitism 135 Chapter 6 Jewish Self-Stereotyping and Jewish &llancipation: Benjamin Farjeon, Amy Levy, Julia Frankau and the Modern Anglo-Jewish Novel 176 Chapter 7 Jewish Self-Stereotyping and Jewish Immigration: Israel Zangwill, Samuel Gordon and the Modern Anglo-Jewish Novel 220 Chapter 8 Jewish Stereotyping and Jewish Nationalism: George Eliot, Proto-Zionism and the Popular aiglish Novel 253 Chapter 9 Jewish Stereotyping and Socialism: H.G. Wells, George Bernard Shaw and the "Socialism of Fools" 292 Chapter 10 Jewish Stereotyping and Jewish Sexuality: George Du Maurier, Henry James and the Fiction of Desire 329 Chapter 11 Conclusion: Why the Jews? Jewish Stereotyping and the Christian Legacy 362 Bibliography 403 ii ACKWLEDGEMENTS This thesis would not have been possible without the guidance of my supervisors, Professor Kenneth Graham and Dr. -

B.A. Hons. Part - I

B.A. Hons. Part - I English Language and Usage-I (Code : ENG 111) Semester : I Credits : 3 Course : 1 No. of contact hours per week : 3 Objective : To familiarize the students with the grammatical structures and their applications. To develop the ability to comprehend and analyse a literary text. Unit 1 (12 Hrs.) Sentence Elements (SVOCA) Use of Modals (from A Practical English Grammar by Thomson and Martinet) Unit 2 (8 Hrs.) Relative Clauses Transformation of Sentences: Passivization, Reported Speech, Change of degrees of adjective. Unit 3 (7Hrs.) Theme Writing Unit 4 (10 Hrs.) Précis Writing (Summarizing) Unit 5 (8 Hrs) CVs and Job Applications Suggested Readings • The Written Word, Vandana R. Singh (OUP) • The Oxford Guide to Writing & Speaking (OUP) John Seely • A University Grammar of English, Quirk & Greenbaum • Write It : Michael Dean (Cambridge University Press) • Guided Paragraph Writing by T. C. Jupp & John Milne • A Practical English Grammar by A.J. Thomson and A.V.Martinet B.A. Hons.Part-I The English Renaissance and Metaphysical Age -I (Code : ENG 112) Semester : I Credits : 4 Course : 2 No. of Contact Hrs./Week : 4 Objective : To Familiarize the students with the respective literary ages and their salient features; various literary movements and trends and the representative poets and their individual traits. Unit 1 (14 Hrs.) B. Jonson Every Man in His Humour Unit 2 (14 Hrs.) W. Shakespeare Twelfth Night Unit 3 (10 Hrs.) Edmund Spenser Of this World’s Theatre in which we stay.. (54) Most Glorious Lord of Lyfe, that on this day… One day I wrote her name upon the strand (75) (Sonnets from “Amoretti”) Unit 4 (12 Hrs.) John Donne The Good Morrow, Woman’s Constancy Death, be not Proud Goe & Catche a Falling Starre Loves Alchymie, Song – Sweetest Love I do not go.. -

A Comparative Analysis of Poetic Structure As the Primary Determinant of Musical Form in Selected a Cappella Choral Works of Gerald Finzi and Benjamin Britten

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Spring 5-2008 A Comparative Analysis of Poetic Structure as the Primary Determinant of Musical Form in Selected A Cappella Choral Works of Gerald Finzi and Benjamin Britten Andrew Malcolm Jensen University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Composition Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Jensen, Andrew Malcolm, "A Comparative Analysis of Poetic Structure as the Primary Determinant of Musical Form in Selected A Cappella Choral Works of Gerald Finzi and Benjamin Britten" (2008). Dissertations. 1109. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1109 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF POETIC STRUCTURE AS THE PRIMARY DETERMINANT OF MUSICAL FORM IN SELECTED A CAPPELLA CHORAL WORKS OF GERALD FINZI AND BENJAMIN BRITTEN by Andrew Malcolm Jensen A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts Approved May 2008 COPYRIGHT BY ANDREW MALCOLM JENSEN 2008 The University of Southern Mississippi A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF POETIC STRUCTURE AS THE PRIMARY -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} from James to Eliot by Boris Ford Boris Ford

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} From James to Eliot by Boris Ford Boris Ford. Richard Boris Ford (1 July 1917 in India – 19 May 1998), [1] [2] known as Boris Ford , was a literary critic, writer, and educationist. Contents. Early life [ edit | edit source ] The son of an Indian Army officer, Brigadier Geoffrey Noel Ford, and his Russian wife Ekaterina, [3] Ford was a chorister at King's College, Cambridge, eventually becoming head chorister. [4] He was then educated at Gresham's School, and through his English master there, Denys Thompson, was introduced to F.R. Leavis under whom he studied at Downing College, Cambridge. [2] [3] Even before graduating, Ford's essay on Wuthering Heights was published by Leavis in Scrutiny in March 1939. Although he came to share many of Leavis's ideas, Ford could not follow Leavis in making "exclusion and exclusivity major features of [Leavis's] critical policy". [2] Ford had an increasingly stormy relationship with Leavis and his wife Q. D.: at one point, Q. D. wrote to him "Mrs Leavis informs Mr Ford that he is no longer an acceptable visitor to her house. Any communications from him will not be answered." [1] Career [ edit | edit source ] After Cambridge, Ford joined the army, and from 1940 until the end of the Second World War was the officer commanding the Middle East School of Artistic Studies. [1] He then became chief editor and director of the Army Bureau of Current Affairs (ABCA). So critical of Britain were ABCA's seminars addressed to officers and men that Ford attracted the attention of MI5. -

685-Cs 2Q0 700 Edrs Price Mf-$0.65 Hc-$3.29

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 022 200 CS 200 684 TITLE Anglo-American Seminar on the Teaching and Learning of English Agenda (Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire, Aug. 20-Sept. 16, 1966); and Miscellaneous Papers: Freshman English, English in English Departments of English Universities, Some Technical Terms; and The Breadth and Depth of English in the United States. INSTITUTION Modern Language Association of America, New York, N.Y.; National Association for the Teaching of English (England).; National Council of Teachers of English, Champaign, Ill. PUB DATE Sep 66 NOTE 93p.; For text of the working papers see CS 200 685-CS 2Q0 700 EDRS PRICE MF-$0.65 HC-$3.29 DESCRIPTORS College freshmen; Conference Reports; Definitions; English Departments; *English Instruction; Language Standardization; Sociolinguistics; Tutorial Programs IDENTIFIERS *Dartmouth Seminar on the Teaching of English ABSTRACT The Anglo-American Conference held at Dartmouth College .in the summer of 1966, was designed to improve the teaching of English and the cooperation between scholars and teachers in Great Britain, Canada, and the United States. Major issues in English education were identified in advance of the conference. Papers on these topics were discussed at an early plenary session and then referred for further consideration to a working party. This agenda contains: a daily calendar of seminar events; working party and study group assignments; names, addresses, and biographies of participants and staff; and a guide to the community cf Hanover and points of interest in New England. Miscellaneous paiiers are included. "Freshman English" discusses and evaluates a tutorial method of teaching. Freshman English at Berkeley. "English in English Departments of English Universities" discusses functions and goals of-English departments. -

Benjamin Britten's Absorption of and Contribution to the Lied

Benjamin Britten’s absorption of and contribution to the Lied tradition Paul Higgins Benjamin Britten (1913-1976) grew up in a musical household. His mother was a keen amateur singer who was active in the local Choral Society and also encouraged the family’s musical entertainment of guests. In his contribution to Mitchell and Keller’s 1952 book, Peter Pears lists the repertory performed in the Britten household; prominent among this repertoire are the songs of Schubert, Schumann and Brahms and of lesser significance some lighter weight songs of Arthur Sullivan, ballads of Liza Lehmann and others, and some few folk songs,1 thus highlighting the relative importance of German Lieder as a formative influence on this young composer. From an early age Britten’s role in this musical household was to provide the piano accompaniment for his mother’s voice, who performed her son’s early settings; this formative experience of writing for and accompanying high voice was to become a significant and permanent of Britten’s vocal writing style. This article seeks to identify and critically assess the significance of art song to Britten’s compositional achievements; while addressing specifically the genres of solo art song with instrumental accompaniment and orchestral song, it excludes the consideration of Britten’s vocal duets, trios and dramatic works. This selection reflects the fact that it is in these two genres that Britten approaches most directly the origins of the German art song tradition. In addressing solo-voice art song, the following, separate yet inter-related questions are central to an understanding of Britten’s engagement with English art song: What attracted Britten to the genre of art song? Was this association consistent throughout his career? How did the tradition of art song form and shape his aesthetic view of the artist in society? And, finally, how did he build upon these traditions and make his own contribution to this genre? 1 Peter Pears: ‘The Vocal Music’ Benjamin Britten a Commentary on his Works from a Group of Specialists, ed. -

Old Greshamian Magazine CONTENTS

Old Greshamian Magazine CONTENTS Calendar of Events ......................................................................................................3 Chairmans Notes ........................................................................................................4 Minutes of A.G.M....................................................................................................5-7 Accounts..................................................................................................................9-10 Staff Lists...............................................................................................................12-14 Obituaries..............................................................................................................16-41 News.......................................................................................................................43-55 The Edinburgh House Dinner .................................................................................56 Class of 1989 Reunion...............................................................................................56 The Old School House Dinner.................................................................................57 Reunion Dinner in Newquay ...................................................................................59 Philip Newell Awards...........................................................................................60-64 Marriages and Engagements ....................................................................................65 -

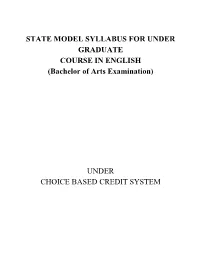

STATE MODEL SYLLABUS for UNDER GRADUATE COURSE in ENGLISH (Bachelor of Arts Examination)

STATE MODEL SYLLABUS FOR UNDER GRADUATE COURSE IN ENGLISH (Bachelor of Arts Examination) UNDER CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM Course structure of UG English Honours Semester Course Course Name Credits Total marks I AEC-I AEC-I 04 100 C-I British Poetry and Drama: 14th 06 100 to 17th Centuries C-II British Poetry and Drama: 17th 06 and 18th Century 100 GE-I Academic Writing and 06 100 Composition 22 II AEC-II AEC-II 04 100 C-III British Prose: 18th Century 06 100 C-IV Indian Writing in English 06 100 GE-II Gender and Human Rights 06 100 22 III C-V British Romantic Literature 06 100 th C-VI British Literature 19 Century 06 100 C-VII British Literature: Early 20th 06 100 Century GE-III Nation, Culture, India 06 100 SEC-I SEC-I 04 100 28 IV C-VIII American Literature 06 100 C-IX European Classical Literature 06 100 C-X 06 100 Women’s Writing GE-IV Language and Linguistics 06 100 SEC-II SEC-II 04 100 28 Semester Course Course Name Credits Total marks V C-XI 06 100 Modern European Drama C-XII 06 100 Indian Classical Literature DSE-I Literary Theory 06 100 DSE-II 06 100 World Literature 24 VI C-XIII Postcolonial Literatures 06 100 C-XIV Popular Literature 06 100 DSE-III 06 100 Partition Literature DSE-IV Writing for Mass Media 06 100 OR DSE-IV Dissertation 06 100* 24 ENGLISH HONOURS PAPERS: Core Course -14 papers Discipline Specific Elective - 4 papers (3 + 1 paper or Project) Generic Elective for Non English students - 4 Papers.