Benjamin Britten's Absorption of and Contribution to the Lied

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Music-Making in a Joyous Sense”: Democratization, Modernity, and Community at Benjamin Britten's Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts

“Music-making in a Joyous Sense”: Democratization, Modernity, and Community at Benjamin Britten's Aldeburgh Festival of Music and the Arts Daniel Hautzinger Candidate for Senior Honors in History Oberlin College Thesis Advisor: Annemarie Sammartino Spring 2016 Hautzinger ii Table of Contents 1. Introduction 1 2. Historiography and the Origin of the Festival 9 a. Historiography 9 b. The Origin of the Festival 14 3. The Democratization of Music 19 4. Technology, Modernity, and Their Dangers 31 5. The Festival as Community 39 6. Conclusion 53 7. Bibliography 57 a. Primary Sources 57 b. Secondary Sources 58 Hautzinger iii Acknowledgements This thesis would never have come together without the help and support of several people. First, endless gratitude to Annemarie Sammartino. Her incredible intellect, voracious curiosity, outstanding ability for drawing together disparate strands, and unceasing drive to learn more and know more have been an inspiring example over the past four years. This thesis owes much of its existence to her and her comments, recommendations, edits, and support. Thank you also to Ellen Wurtzel for guiding me through my first large-scale research paper in my third year at Oberlin, and for encouraging me to pursue honors. Shelley Lee has been an invaluable resource and advisor in the daunting process of putting together a fifty-some page research paper, while my fellow History honors candidates have been supportive, helpful in their advice, and great to commiserate with. Thank you to Steven Plank and everyone else who has listened to me discuss Britten and the Aldeburgh Festival and kindly offered suggestions. -

Britten’S Ever-Fresh Musical Ideas, Create a Work of Charm and Considerable Dramatic Impetus

CMYK N Composed in a remarkably fecund period following the success of Peter Grimes, the 1948 cantata AXOS St Nicolas wedded amateur chorus with professional soloists and string orchestra in a highly effective re-telling of the story. The unusual forces, together with Britten’s ever-fresh musical ideas, create a work of charm and considerable dramatic impetus. The companion work on this CD is the rarely-heard 8.557203 student work Christ’s Nativity of 1931, featuring a carefully chosen sequence of texts to unify this short DDD suite. These fresh and atmospheric accounts were originally released on Collins Classics. 8.557203 Benjamin Playing Time BRITTEN 66:00 (1913-1976) 1 - 9 St Nicolas, Op. 42 45:20 BRITTEN: A Cantata 0 - $ Christ’s Nativity 16:19 Christmas Suite for Chorus (1931) % Psalm 150, Op. 67 4:21 St Nicolas St Nicolas Tracks 1 - 9 Philip Langridge, Tenor • Tallis Chamber Choir • English Chamber Orchestra Tracks 0 - $ BBC Singers www.naxos.com Made in E.C. Sung texts in English Booklet notes in English • Kommentar auf Deutsch h h Track % New London Children’s Choir • London Schools Symphony Orchestra & 1996 Lambourne Productions Ltd. Tracks 1 - % Steuart Bedford g 2003 HNH International Ltd. BRITTEN: Recorded at All Hallows, Gospel Oak, London Tracks 1 - 9 and % recorded 16th-17th March 1996 Producer: John H West • Engineer: Mike Hatch, Floating Earth Music Publishers: Boosey & Hawkes Music Publishers Limited Tracks 0 - $ recorded 21st March 1996 Producer: Michael Emery • Digital Editor: Marvin Ware • Balance Engineer: Mike Hatch, Floating Earth Music Publishers: Faber Music • MCPS • Text to St Nicolas g 1948 by Boosey & Co Ltd. -

Literature, Politics, and the University, 1932–19651

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by King's Research Portal King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1093/english/efw011 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Hutton, A. (2016). An English School for the Welfare State: Literature, Politics, and the University, 1932-1965. ENGLISH, 65(248), 3-34. https://doi.org/10.1093/english/efw011 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

Guitar Syllabus

TheThe LLeinsteinsteerr SScchoolhool ooff MusMusiicc && DDrramama Established 1904 Singing Grade Examinations Syllabus The Leinster School of Music & Drama Singing Grade Examinations Syllabus Contents The Leinster School of Music & Drama ____________________________ 2 General Information & Examination Regulations ____________________ 4 Grade 1 ____________________________________________________ 6 Grade 2 ____________________________________________________ 9 Grade 3 ____________________________________________________ 12 Grade 4 ____________________________________________________ 15 Grade 5 ____________________________________________________ 19 Grade 6 ____________________________________________________ 23 Grade 7 ____________________________________________________ 27 Grade 8 ____________________________________________________ 33 Junior & Senior Repertoire Recital Programmes ________________________ 35 Performance Certificate __________________________________________ 36 1 The Leinster School of Music & Drama Singing Grade Examinations Syllabus TheThe LeinsterLeinster SchoolSchool ofof MusicMusic && DraDrammaa Established 1904 "She beckoned to him with her finger like one preparing a certificate in pianoforte... at the Leinster School of Music." Samuel Beckett Established in 1904 The Leinster School of Music & Drama is now celebrating its centenary year. Its long-standing tradition both as a centre for learning and examining is stronger than ever. TUITION Expert individual tuition is offered in a variety of subjects: • Singing and -

Spring/Summer 2016

News for Friends of Leonard Bernstein Spring/Summer 2016 High-brow, Low-brow, All-brow Bernstein, Gershwin, Ellington, and the Richness of American Music © VICTOR © VICTOR KRAFT by Michael Barrett uch of my professional life has been spent on convincing music lovers Mthat categorizing music as “classical” or “popular” is a fool’s errand. I’m not surprised that people s t i l l c l i n g t o t h e s e d i v i s i o n s . S o m e w h o love classical masterpieces may need to feel reassured by their sophistication, looking down on popular culture as dis- posable and inferior. Meanwhile, pop music fans can dismiss classical music lovers as elitist snobs, out of touch with reality and hopelessly “square.” Fortunately, music isn’t so black and white, and such classifications, especially of new music, are becoming ever more anachronistic. With the benefit of time, much of our country’s greatest music, once thought to be merely “popular,” is now taking its rightful place in the category of “American Classics.” I was educated in an environment that was dismissive of much of our great American music. Wanting to be regarded as a “serious” musician, I found myself going along with the thinking of the times, propagated by our most rigid conservatory student in the 1970’s, I grew work that studiously avoided melody or key academic composers and scholars of up convinced that Aaron Copland was a signature. the 1950’s -1970’s. These wise men (and “Pops” composer, useful for light story This was the environment in American yes, they were all men) had constructed ballets, but not much else. -

Recordings of Mahler Symphony No. 4

Recordings of Mahler Symphony No. 4 by Stan Ruttenberg, President, Colorado MahlerFest SUMMARY After listening to each recording once or twice to get the general feel, on bike rides, car trips, while on the Internet etc, I then listened more carefully, with good headphones, following the score. They are listed in the survey in about the order in which I listened, and found to my delight, and disgust, that as I went on I noticed more and more details to which attention should be paid. Lack of time and adequate gray matter prevented me from going back and re-listening all over again, except for the Mengelberg and Horenstein recordings, and I did find a few points to change or add. I found that JH is the ONLY conductor to have the piccolos play out adequately in the second movement, and Claudio Abbado with the Vienna PO is the only conductor who insisted on the two horn portamenti in the third movement.. Stan's prime picks: Horenstein, Levine, Reiner, Szell, Skrowaczewski, von Karajan, Abravanel, in that order, but the rankings are very close. Also very good are Welser- Most, and Klemperer with Radio Orchestra Berlin, and Berttini at Cologne. Not one conductor met all my tests of faithfulness to the score in all the too many felicities therein, but these did the best and at the same time produced a fine overall performance. Mengelberg, in a class by himself, should be heard for reference. Stan's soloist picks: Max Cencic (boy soprano with Nanut), in a class by himself. Then come, not in order, Davrath (Abravanel), Mathes (von Karajan), Trötschel (Klemperer BRSO), Raskin (Szell), Blegen (Levine), Della Casa (Reiner), Irmgard Seefried (Walter), Jo Vincent (Mengelberg), Ameling (Haitink RCOA), Ruth Zeisek (Gatti), Margaret Price with Horenstein, and Kiri Te Kanawa (Solti), Szell (Rattle broadcast), and Battle (Maazel). -

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS His Broadcasting Career Covers Both Radio and Television

557643bk VW US 16/8/05 5:02 pm Page 5 8.557643 Iain Burnside Songs of Travel (Words by Robert Louis Stevenson) 24:03 1 The Vagabond 3:24 The English Song Series • 14 DDD Iain Burnside enjoys a unique reputation as pianist and broadcaster, forged through his commitment to the song 2 Let Beauty awake 1:57 repertoire and his collaborations with leading international singers, including Dame Margaret Price, Susan Chilcott, 3 The Roadside Fire 2:17 Galina Gorchakova, Adrianne Pieczonka, Amanda Roocroft, Yvonne Kenny and Susan Bickley; David Daniels, 4 John Mark Ainsley, Mark Padmore and Bryn Terfel. He has also worked with some outstanding younger singers, Youth and Love 3:34 including Lisa Milne, Sally Matthews, Sarah Connolly; William Dazeley, Roderick Williams and Jonathan Lemalu. 5 In Dreams 2:18 VAUGHAN WILLIAMS His broadcasting career covers both radio and television. He continues to present BBC Radio 3’s Voices programme, 6 The Infinite Shining Heavens 2:15 and has recently been honoured with a Sony Radio Award. His innovative programming led to highly acclaimed 7 Whither must I wander? 4:14 recordings comprising songs by Schoenberg with Sarah Connolly and Roderick Williams, Debussy with Lisa Milne 8 Songs of Travel and Susan Bickley, and Copland with Susan Chilcott. His television involvement includes the Cardiff Singer of the Bright is the ring of words 2:10 World, Leeds International Piano Competition and BBC Young Musician of the Year. He has devised concert series 9 I have trod the upward and the downward slope 1:54 The House of Life • Four poems by Fredegond Shove for a number of organizations, among them the acclaimed Century Songs for the Bath Festival and The Crucible, Sheffield, the International Song Recital Series at London’s South Bank Centre, and the Finzi Friends’ triennial The House of Life (Words by Dante Gabriel Rossetti) 26:27 festival of English Song in Ludlow. -

Benjamin Britten: a Catalogue of the Orchestral Music

BENJAMIN BRITTEN: A CATALOGUE OF THE ORCHESTRAL MUSIC 1928: “Quatre Chansons Francaises” for soprano and orchestra: 13 minutes 1930: Two Portraits for string orchestra: 15 minutes 1931: Two Psalms for chorus and orchestra Ballet “Plymouth Town” for small orchestra: 27 minutes 1932: Sinfonietta, op.1: 14 minutes Double Concerto in B minor for Violin, Viola and Orchestra: 21 minutes (unfinished) 1934: “Simple Symphony” for strings, op.4: 14 minutes 1936: “Our Hunting Fathers” for soprano or tenor and orchestra, op. 8: 29 minutes “Soirees musicales” for orchestra, op.9: 11 minutes 1937: Variations on a theme of Frank Bridge for string orchestra, op. 10: 27 minutes “Mont Juic” for orchestra, op.12: 11 minutes (with Sir Lennox Berkeley) “The Company of Heaven” for two speakers, soprano, tenor, chorus, timpani, organ and string orchestra: 49 minutes 1938/45: Piano Concerto in D major, op. 13: 34 minutes 1939: “Ballad of Heroes” for soprano or tenor, chorus and orchestra, op.14: 17 minutes 1939/58: Violin Concerto, op. 15: 34 minutes 1939: “Young Apollo” for Piano and strings, op. 16: 7 minutes (withdrawn) “Les Illuminations” for soprano or tenor and strings, op.18: 22 minutes 1939-40: Overture “Canadian Carnival”, op.19: 14 minutes 1940: “Sinfonia da Requiem”, op.20: 21 minutes 1940/54: Diversions for Piano(Left Hand) and orchestra, op.21: 23 minutes 1941: “Matinees musicales” for orchestra, op. 24: 13 minutes “Scottish Ballad” for Two Pianos and Orchestra, op. 26: 15 minutes “An American Overture”, op. 27: 10 minutes 1943: Prelude and Fugue for eighteen solo strings, op. 29: 8 minutes Serenade for tenor, horn and strings, op. -

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company

A Culture of Recording: Christopher Raeburn and the Decca Record Company Sally Elizabeth Drew A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Sheffield Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Music This work was supported by the Arts & Humanities Research Council September 2018 1 2 Abstract This thesis examines the working culture of the Decca Record Company, and how group interaction and individual agency have made an impact on the production of music recordings. Founded in London in 1929, Decca built a global reputation as a pioneer of sound recording with access to the world’s leading musicians. With its roots in manufacturing and experimental wartime engineering, the company developed a peerless classical music catalogue that showcased technological innovation alongside artistic accomplishment. This investigation focuses specifically on the contribution of the recording producer at Decca in creating this legacy, as can be illustrated by the career of Christopher Raeburn, the company’s most prolific producer and specialist in opera and vocal repertoire. It is the first study to examine Raeburn’s archive, and is supported with unpublished memoirs, private papers and recorded interviews with colleagues, collaborators and artists. Using these sources, the thesis considers the history and functions of the staff producer within Decca’s wider operational structure in parallel with the personal aspirations of the individual in exerting control, choice and authority on the process and product of recording. Having been recruited to Decca by John Culshaw in 1957, Raeburn’s fifty-year career spanned seminal moments of the company’s artistic and commercial lifecycle: from assisting in exploiting the dramatic potential of stereo technology in Culshaw’s Ring during the 1960s to his serving as audio producer for the 1990 The Three Tenors Concert international phenomenon. -

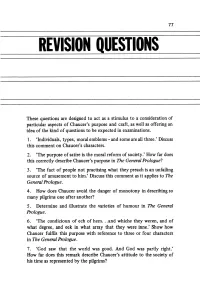

Revision Questions

77 REVISION QUESTIONS These questions are designed to act as a stimulus to a consideration of particular aspects of Chaucer's purpose and craft, as well as offering an idea of the kind of questions to be expected in examinations. 1. 'Individuals, types, moral emblems - and some are all three.' Discuss this comment on Chaucer's characters. 2. 'The purpose ofsatire is the moral reform ofsociety.' How far does this correctly describe Chaucer's purpose in The General Prologue? 3. 'The fact of people not practising what they preach is an unfailing source of amusement to him.' Discuss this comment as it applies to The General Prologue. 4. How does Chaucer avoid the danger of monotony in describing so many pilgrims one after another? 5. Determine and illustrate the varieties of humour in The General Prologue. 6. 'The condicioun of ech of hem ...and whiche they weren, and of what degree, and eek in what array that they were inne.' Show how Chaucer fulfils this purpose with reference to three or four characters in The General Prologue. 7. 'God saw that the world was good. And God was partly right.' How far does this remark describe Chaucer's attitude to the society of his time as represented by the pilgrims? 79 FURTHER READING Long book lists can be both daunting and useless, if a student cannot decide what will be of immediate interest to him. For this reason this bibliography has been kept very short. Its purpose is merely to point in one or two useful directions; further signposts are plentiful as soon as any of these books are examined. -

Britten Connections a Guide for Performers and Programmers

Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Britten –Pears Foundation Telephone 01728 451 700 The Red House, Golf Lane, [email protected] Aldeburgh, Suffolk, IP15 5PZ www.brittenpears.org Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers by Paul Kildea Contents The twentieth century’s Programming tips for 03 consummate musician 07 13 selected Britten works Britten connected 20 26 Timeline CD sampler tracks The Britten-Pears Foundation is grateful to Orchestra, Naxos, Nimbus Records, NMC the following for permission to use the Recordings, Onyx Classics. EMI recordings recordings featured on the CD sampler: BBC, are licensed courtesy of EMI Classics, Decca Classics, EMI Classics, Hyperion Records, www.emiclassics.com For full track details, 28 Lammas Records, London Philharmonic and all label websites, see pages 26-27. Index of featured works Front cover : Britten in 1938. Photo: Howard Coster © National Portrait Gallery, London. Above: Britten in his composition studio at The Red House, c1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton . 29 Further information Opposite left : Conducting a rehearsal, early 1950s. Opposite right : Demonstrating how to make 'slung mugs' sound like raindrops for Noye's Fludde , 1958. Photo: Kurt Hutton. Britten Connections A guide for performers and programmers 03 The twentieth century's consummate musician In his tweed jackets and woollen ties, and When asked as a boy what he planned to be He had, of course, a great guide and mentor. with his plummy accent, country houses and when he grew up, Britten confidently The English composer Frank Bridge began royal connections, Benjamin Britten looked replied: ‘A composer.’ ‘But what else ?’ was the teaching composition to the teenage Britten every inch the English gentleman. -

That to See How Britten Handles the Dramatic and Musical Materials In

BOOKS 131 that to see how Britten handles the dramatic and musical materials in the op- era is "to discover anew how from private pain the great artist can fashion some- thing that transcends his own individual experience and touches all humanity." Given the audience to which it is directed, the book succeeds superbly. Much of it is challenging and stimulating intellectually, while avoiding exces- sive weightiness, and at the same time, it is entertaining in the very best sense of the word. Its format being what it is, there are inevitable duplications of information, and I personally found the Garbutt and Garvie articles less com- pelling than the remainder of the book. The last two articles of Brett's, excel- lent as they are, also tend to be a little discursive, but these are minor reserva- tions. For anyone who cares for this masterwork of twentieth-century opera, Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/oq/article/4/3/131/1587210 by guest on 01 October 2021 or for Britten and his music, this book is obligatory reading. Carlisle Floyd Peter Grimes/Gloriana Benjamin Britten English National Opera/Royal Opera Guide 24 Nicholas John, series editor London: John Calder; New York: Riverrun Press, 1983 128 pages, $5.95 (paper) The English National Opera/Royal Opera Guides, small paperbacks with siz- able contents, are among the best introductions available to the thirty-plus operas published in the series so far. Each guide includes some essays by ac- knowledged authorities on various aspects of its subject, followed by a table of major musical themes, a complete libretto (original language plus transla- tion), a brief bibliography, and a discography.