1 Introduction: 'The Sun Is Gone Down'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Checklist of Publications and Discoveries in 2013

ARTICLE Part II: Reproductions of Drawings and Paintings Section A: Illustrations of Individual Authors Section B: Collections and Selections Part III: Commercial Engravings Section A: Illustrations of Individual Authors William Blake and His Circle: Part IV: Catalogues and Bibliographies A Checklist of Publications and Section A: Individual Catalogues Section B: Collections and Selections Discoveries in 2013 Part V: Books Owned by William Blake the Poet Part VI: Criticism, Biography, and Scholarly Studies By G. E. Bentley, Jr. Division II: Blake’s Circle Blake Publications and Discoveries in 2013 with the assistance of Hikari Sato for Japanese publications and of Fernando 1 The checklist of Blake publications recorded in 2013 in- Castanedo for Spanish publications cludes works in French, German, Japanese, Russian, Span- ish, and Ukrainian, and there are doctoral dissertations G. E. Bentley, Jr. ([email protected]) is try- from Birmingham, Cambridge, City University of New ing to learn how to recognize the many styles of hand- York, Florida State, Hiroshima, Maryland, Northwestern, writing of a professional calligrapher like Blake, who Oxford, Universidade Federal de Santa Maria, Voronezh used four distinct hands in The Four Zoas. State, and Wrocław. The Folio Society facsimile of Blake’s designs for Gray’s Poems and the detailed records of “Sale Editors’ notes: Catalogues of Blake’s Works 1791-2013” are likely to prove The invaluable Bentley checklist has grown to the point to be among the most lastingly valuable of the works listed. where we are unable to publish it in its entirety. All the material will be incorporated into the cumulative Gallica “William Blake and His Circle” and “Sale Catalogues of William Blake’s Works” on the Bentley Blake Collection 2 A wonderful resource new to me is Gallica <http://gallica. -

Issues) and Begin with the Summer Issue

VOLUME 22 NUMBER 3 WINTER 1988/89 ■iiB ii ••▼•• w BLAKE/AN ILLUSTRATED QUARTERLY WINTER 1988/89 REVIEWS 103 William Blake, An Island in the Moon: A Facsimile of the Manuscript Introduced, Transcribed, and Annotated by Michael Phillips, reviewed by G. E. Bentley, Jr. 105 David Bindman, ed., William Blake's Illustrations to the Book of Job, and Colour Versions of William- Blake 's Book of job Designs from the Circle of John Linnell, reviewed by Martin Butlin AN ILLUSTRATED QUARTERLY VOLUME 22 NUMBER 3 WINTER 1988/89 DISCUSSION 110 An Island in the Moon CONTENTS Michael Phillips 80 Canterbury Revisited: The Blake-Cromek Controversy by Aileen Ward CONTRIBUTORS 93 The Shifting Characterization of Tharmas and Enion in Pages 3-7 of Blake's Vala or The FourZoas G. E. BENTLEY, JR., University of Toronto, will be at by John B. Pierce the Department of English, University of Hyderabad, India, through November 1988, and at the National Li• brary of Australia, Canberra, from January-April 1989. Blake Books Supplement is forthcoming. MARTIN BUTLIN is Keeper of the Historic British Col• lection at the Tate Gallery in London and author of The Paintings and Drawings of William Blake (Yale, 1981). MICHAEL PHILLIPS teaches English literature at Edinburgh University. A monograph on the creation in J rrfHRurtfr** fW^F *rWr i*# manuscript and "Illuminated Printing" of the Songs of Innocence and Songs ofExperience is to be published in 1989 by the College de France. JOHN B. PIERCE, Assistant Professor in English at the University of Toronto, is currently at work on the manu• script of The Four Zoas. -

Literature, Politics, and the University, 1932–19651

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by King's Research Portal King’s Research Portal DOI: 10.1093/english/efw011 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication record in King's Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Hutton, A. (2016). An English School for the Welfare State: Literature, Politics, and the University, 1932-1965. ENGLISH, 65(248), 3-34. https://doi.org/10.1093/english/efw011 Citing this paper Please note that where the full-text provided on King's Research Portal is the Author Accepted Manuscript or Post-Print version this may differ from the final Published version. If citing, it is advised that you check and use the publisher's definitive version for pagination, volume/issue, and date of publication details. And where the final published version is provided on the Research Portal, if citing you are again advised to check the publisher's website for any subsequent corrections. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognize and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. •Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. •You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain •You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the Research Portal Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. -

William Blake's Songs of Innocence and of Experience: from Innocence to Experience to Wise Innocence Robert W

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1977 William Blake's Songs of Innocence and of Experience: From Innocence to Experience to Wise Innocence Robert W. Winkleblack Eastern Illinois University This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Winkleblack, Robert W., "William Blake's Songs of Innocence and of Experience: From Innocence to Experience to Wise Innocence" (1977). Masters Theses. 3328. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/3328 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PAPER CERTIFICATE #2 TO: Graduate Degree Candidates who have written formal theses. SUBJECT: Permission to reproduce theses. The University Library is receiving a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclusion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. Please sign one of the following statements: Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. �S"Date J /_'117 Author I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University not allow my thesis be reproduced because ��--��- Date Author pdm WILLIAM BLAKE'S SONGS OF INNOCENCE AND OF EXPERIENCE: - FROM INNOCENCE TO EXPERIENCE TO WISE INNOCENCE (TITLE) BY Robert W . -

Alicia Ostriker, Ed., William Blake: the Complete Poems

REVIEW Alicia Ostriker, ed., William Blake: The Complete Poems John Kilgore Blake/An Illustrated Quarterly, Volume 12, Issue 4, Spring 1979, pp. 268-270 268 psychological—carried by Turner's sublimely because I find myself in partial disagreement with overwhelming sun/god/king/father. And Paulson argues Arnheim's contention "that any organized entity, in that the vortex structure within which this sun order to be grasped as a whole by the mind, must be characteristically appears grows as much out of translated into the synoptic condition of space." verbal signs and ideas ("turner"'s name, his barber- Arnheim seems to believe, not only that all memory father's whorled pole) as out of Turner's early images of temporal experiences are spatial, but that sketches of vortically copulating bodies. Paulson's they are also synoptic, i.e. instantaneously psychoanalytical speculations are carried to an perceptible as a comprehensive whole. I would like extreme by R. F. Storch who argues, somewhat to suggest instead that all spatial images, however simplistically, that Shelley's and Turner's static and complete as objects, are experienced tendencies to abstraction can be equated with an temporally by the human mind. In other works, we alternation between aggression toward women and a "read" a painting or piece of sculpture or building dream-fantasy of total love. Storch then applauds in much the same way as we read a page. After Constable's and Wordsworth's "sobriety" at the isolating the object to be read, we begin at the expense of Shelley's and Turner's overly upper left, move our eyes across and down the object; dissociated object-relations, a position that many when this scanning process is complete, we return to will find controversial. -

The Visionary Company

WILLIAM BLAKE 49 rible world offering no compensations for such denial, The] can bear reality no longer and with a shriek flees back "unhinder' d" into her paradise. It will turn in time into a dungeon of Ulro for her, by the law of Blake's dialectic, for "where man is not, nature is barren"and The] has refused to become man. The pleasures of reading The Book of Thel, once the poem is understood, are very nearly unique among the pleasures of litera ture. Though the poem ends in voluntary negation, its tone until the vehement last section is a technical triumph over the problem of depicting a Beulah world in which all contraries are equally true. Thel's world is precariously beautiful; one false phrase and its looking-glass reality would be shattered, yet Blake's diction re mains firm even as he sets forth a vision of fragility. Had Thel been able to maintain herself in Experience, she might have re covered Innocence within it. The poem's last plate shows a serpent guided by three children who ride upon him, as a final emblem of sexual Generation tamed by the Innocent vision. The mood of the poem culminates in regret, which the poem's earlier tone prophe sied. VISIONS OF THE DAUGHTERS OF ALBION The heroine of Visions of the Daughters of Albion ( 1793), Oothoon, is the redemption of the timid virgin Thel. Thel's final griefwas only pathetic, and her failure of will a doom to vegetative self-absorption. Oothoon's fate has the dignity of the tragic. -

William Blake PART I

126 Of the fifty-three more-or-less complete copies of Blake's writings in private hands, only one has moved to a public collection: VICTORIA UNIVERSITY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO. This is Songs of Innocence and of Experience (i), a posthumous copy watermarked with fragments of J WHATMAN | 1831, lacking ten of fifty-four prints. A curious feature of copy i is that one print (pl. 23) is watercoloured (see Illus. 1A), perhaps by Catherine Blake (d. 18 October 1831 [BR (2) 546]) or Frederick Tatham who printed the posthumous copies of Blake's works in Illuminated Printing. The colouring is distinct from the colour-printed copy of the same etching in VICTORIA UNIVERSITY IN THE UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO. The public appearance of Songs (i) has permitted the correction of minor errors in the account of it in Blake Books. COPIES UNTRACED America (S), Book of Thel (S), Descriptive Catalogue (V), Europe (N), First Book of Urizen (K), For Children (F), Poetical Sketches (Q), Songs of Innocence and of Experience (CC, q), "To the Public", Visions (S) are untraced. Six of these ten untraced copies in Illuminated Printing - - America (S), Book of Thel (S), Europe (N), First Book of Urizen (K), For Children (F), and Visions (S) -- have not been recorded since they were sold for the Flaxman family in 1862. Some or all the untraced copies may have been destroyed. Division I: William Blake PART I 126 127 ORIGINAL EDITIONS, FACSIMILES,93 REPRINTS, AND TRANSLATIONS Section A: Original Editions TABLE OF COLLECTIONS ADDENDA Biblioteca La Solana ILLUMINATED WORK: For Children: The Gates of Paradise, pl. -

Issues) and Begin (Cambridge UP, 1995), Has Recently Retired from Mcgill with the Summer Issue

AN ILLUSTRATED QUARTERLY VOLUME 31 NUMBER 1 SUMMER 1997 s-Sola/ce AN ILLUSTRATED QUARTERLY VOLUME 31 NUMBER 1 SUMMER 1997 CONTENTS Articles Angela Esterhammer, Creating States: Studies in the Performative Language of John Milton Blake, Wollstonecraft, and the and William Blake Inconsistency of Oothoon Reviewed by David L. Clark 24 by Wes Chapman 4 Andrew Lincoln, Spiritual History: A Reading of Not from Troy, But Jerusalem: Blake's William Blake's Vala, or The Four Zoas Canon Revision Reviewed by John B. Pierce 29 by R. Paul Yoder \7 20/20 Blake, written and directed by George Coates Lorenz Becher: An Artist in Berne, Reviewed by James McKusick 35 Switzerland by Lorenz Becher 22 Correction Reviews Deborah McCollister 39 Frank Vaughan, Again to the Life of Eternity: William Blake's Illustrations to the Poems of Newsletter Thomas Gray Tyger and ()//;<•/ Tales, Blake Society Web Site, Reviewed by Christopher Heppner 24 Blake Society Program for 1997 39 CONTRIBUTORS Morton D. Paley, Department of English, University of Cali• fornia, Berkeley CA 94720-1030 Email: [email protected] LORENZ BECHER lives and works in Berne, Switzerland as artist, English teacher, and househusband. G. E. Bentley, Jr., 246 MacPherson Avenue, Toronto, Ontario M4V 1A2. The University of Toronto declines to forward mail. WES CHAPMAN teaches in the Department of English at Illi• nois Wesleyan University. He has published a study of gen• Nelson Hilton, Department of English, University of Geor• der anxiety in Thomas Pynchon's Gravity's Rainbow and gia, Athens, GA 30602 has a hypertext fiction and a hypertext poem forthcoming Email: [email protected] from Eastgate Systems. -

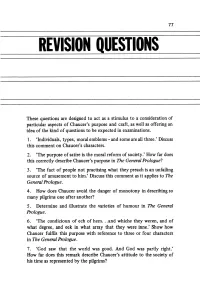

Revision Questions

77 REVISION QUESTIONS These questions are designed to act as a stimulus to a consideration of particular aspects of Chaucer's purpose and craft, as well as offering an idea of the kind of questions to be expected in examinations. 1. 'Individuals, types, moral emblems - and some are all three.' Discuss this comment on Chaucer's characters. 2. 'The purpose ofsatire is the moral reform ofsociety.' How far does this correctly describe Chaucer's purpose in The General Prologue? 3. 'The fact of people not practising what they preach is an unfailing source of amusement to him.' Discuss this comment as it applies to The General Prologue. 4. How does Chaucer avoid the danger of monotony in describing so many pilgrims one after another? 5. Determine and illustrate the varieties of humour in The General Prologue. 6. 'The condicioun of ech of hem ...and whiche they weren, and of what degree, and eek in what array that they were inne.' Show how Chaucer fulfils this purpose with reference to three or four characters in The General Prologue. 7. 'God saw that the world was good. And God was partly right.' How far does this remark describe Chaucer's attitude to the society of his time as represented by the pilgrims? 79 FURTHER READING Long book lists can be both daunting and useless, if a student cannot decide what will be of immediate interest to him. For this reason this bibliography has been kept very short. Its purpose is merely to point in one or two useful directions; further signposts are plentiful as soon as any of these books are examined. -

Invention, Memory, and Place

!"#$"%&'"()*$+',-()."/)01.2$ 34%5',6789):/;.,/)<=)>.&/ >'4,2$9)?,&%&2.1)!"@4&,-()A'1=)BC()D'=)B)6<&"%$,()BEEE8()FF=)GHIJGKB 04L1&75$/)L-9)The University of Chicago Press >%.L1$)MNO9)http://www.jstor.org/stable/1344120 322$77$/9)EHPEKPBEGE)GE9QE Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Critical Inquiry. http://www.jstor.org Invention, Memory, and Place Edward W. Said Over the past decade, there has been a burgeoning interest in two over- lapping areas of the humanities and social sciences: memory and geogra- phy or, more specifically, the study of human space. -

Hett-Syll-80020-19

The Graduate Center of the City University of New York History Department Hist 80200 Literature of Modern Europe II Thursdays 4:15-6:15 GC 3310A Prof. Benjamin Hett e-mail [email protected] GC office 5404 Office hours Thursdays 2:00-4:00 or by appointment Course Description: This course is intended to provide an introduction to the major themes and historians’ debates on modern European history from the 18th century to the present. We will study a wide range of literature, from what we might call classic historiography to innovative recent work; themes will range from state building and imperialism to war and genocide to culture and sexuality. After completing the course students should have a solid basic grounding in the literature of modern Europe, which will serve as a basis for preparation for oral exams as well as for later teaching and research work. Requirements: In a small seminar class of this nature effective class participation by all students is essential. Students will be expected to take the lead in class discussions: each week one student will have the job of introducing the literature for the week and to bring to class questions for discussion. Over the semester students will write a substantial historiographical paper (approximately 20 pages or 6000 words) on a subject chosen in consultation with me, due on the last day of class, May 13. The paper should deal with a question that is controversial among historians. Students must also submit two short response papers (2-3 pages) on readings for two of the weekly sessions of the course, and I will ask for annotated bibliographies for your historiographical papers on March 28. -

Please Click Here to Download a Review of the Bard: William Blake at Flat Time

The Bard – William Blake at Flat Time House By Henry Whaley Over the last few months, Tate Britain has loudly proclaimed William Blake ‘Rebel, Radical, Revolutionary’; the phrase accompanied posters covering the city, emblazoned with Blake’s dramatic final work. In November, the same work lit up the dome of St Paul’s Cathedral in honour of the artist’s 262nd birthday. More than ever before, the spirit of Blake has stalked the streets of London. Now, Blake has returned to his spiritual home, Peckham. Chris McCabe, curator of The Bard at Flat Time House, who has drawn extensively from Blake’s legacy in his own poetry, confesses his astonishment that Peckham is never named in any of Blake’s poems; indeed it was on the Rye that Blake had his first vision, ‘a tree filled with angels, bright angelic wings bespangling every bough like stars’.1 This is a place that forms the nucleus of Blake’s anti-rationalist thought, a turning point in a life governed by the fantastical. The works on display here are indeed fantastical. We are presented with two examples of poems by Gray illustrated by Blake, ‘The Bard’ and ‘The Fatal Sisters’, part of a larger commission totalling 116 pages undertaken in 1797 for John Flaxman. As McCabe asserts in the exhibition catalogue, to overlook these works based on their commissioned nature is a grave mistake; the rich dialogue between poetry and image that unfolds on these pages is an extension of an exchange taking place well beyond their borders, with Gray’s mythic imagery quoted directly in Blake’s work up to a decade either side of the examples presented.2 1 Alexander Gilchrist, The Life of William Blake, ‘Pictor ignotus’ (London, 1863) p.7 2 Chris McCabe, ‘The Commission as Vision’, The Bard – William Blake at Flat Time House, ed.