Chaucerian Works in the English Renaissance: Editions and Imitations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Amanda Holton University of Reading

Chaucer and Pronominatio Amanda Holton University of Reading Pronominatio, or antonomasia, is the replacement of a proper noun with another noun or adjective or a periphrastic formulation, such as 'Cristes mooder' for Mary.] I apply the term only when the reader needs some knowledge outside the immediate context in order to understand the reference and when the name itself is not given at all in surrounding lines. 2 Pronominatio is a fairly common figure in classical and medieval literature, and Chaucer encountered it in a number of his sources; indeed this article, while it focuses on Chaucer's practice, also indicates how it is used in a range of his sources and analogues. The figure is discussed in various classical and medieval rhetorical manuals, featuring, for example, in the Rhetorica Ad Herennium and in Quintilian' s /nstitutio oratoria3 Chaucer's own use of it as a freestanding figure is sparse, highly selective and often pointed, and reveals mixed feelings about its potential, for he is very conscious of how it can express both grandeur and pomposity, splendour and insincerity. After discussing Chaucer's preferred methods of denoting people and places, this article examines how his use of pronominatio relates to his response to Virgil, and, by extension, how he uses the figure as a marker of epic style in several texts. It then demonstrates how he exploits its more negative possibilities when denoting Diomede in Troilus and Criseyde and Mary in the Prioress's Tale. On the whole Chaucer shows a strong preference for simple and direct naming, and will often reject pronominatio even when he encounters it in a source he otherwise favours stylistically. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: MAKING ENGLISH LOW: A

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: MAKING ENGLISH LOW: A HISTORY OF LAUREATE POETICS, 1399-1616 Christine Maffuccio, Doctor of Philosophy, 2018 Dissertation directed by: Professor Theresa Coletti Department of English My dissertation analyzes lowbrow literary forms, tropes, and modes in the writings of three would-be laureates, writers who otherwise sought to align themselves with cultural and political authorities and who themselves aspired to national prominence: Thomas Hoccleve (c. 1367-1426), John Skelton (c. 1460-1529), and Ben Jonson (1572-1637). In so doing, my project proposes a new approach to early English laureateship. Previous studies assume that aspiration English writers fashioned their new mantles exclusively from high learning, refined verse, and the moral virtues of elite poetry. In the writings and self-fashionings that I analyze, however, these would-be laureates employed literary low culture to insert themselves into a prestigious, international lineage; they did so even while creating personas that were uniquely English. Previous studies have also neglected the development of early laureateship and nationalist poetics across the fifteenth, sixteenth, and seventeenth centuries. Examining the ways that cultural cachet—once the sole property of the elite—became accessible to popular audiences, my project accounts for and depends on a long view. My first two chapters analyze writers whose idiosyncrasies have afforded them a marginal position in literary histories. In Chapter 1, I argue that Hoccleve channels Chaucer’s Host, Harry Bailly, in the Male Regle and the Series. Like Harry, Hoccleve draws upon quotidian London experiences to create a uniquely English writerly voice worthy of laureate status. In Chapter 2, I argue that Skelton enshrine the poet’s own fleeting historical experience in the Garlande of Laurell and Phyllyp Sparowe by employing contrasting prosodies to juxtapose the rhythms of tradition with his own demotic meter. -

PAPERS DELIVERED at SHARP CONFERENCES to DATE (Alphabetically by Author; Includes Meeting Year)

PAPERS DELIVERED AT SHARP CONFERENCES TO DATE (alphabetically by author; includes meeting year) Abel, Jonathan. Cutting, molding, covering: media-sensitive suppression in Japan. 2009 Abel, Trudi Johanna. The end of a genre: postal regulations and the dime novel's demise. 1994 ___________________. When the devil came to Washington: Congress, cheap literature, and the struggle to control reading. 1995 Abreu, Márcia Azevedo. Connected by fiction: the presence of the European novel In Brazil. 2013 Absillis, Kevin. Angele Manteau and the Indonesian connection: a remarkable story of Flemish book trade (1958-1962). 2006 ___________. The biggest scam in Flemish literature? On the question of linguistic gatekeeping In literary publishing. 2009 ___________. Pascale Casanova's The World Republic of Letters and the analysis of centre-periphery relations In literary book publishing. 2008 ___________. The printing press and utopia: why imaginary geographies really matter to book history. 2013 Acheson, Katherine O. The Renaissance author in his text. 1994 Acerra, Eleonora. See Louichon, Brigitte (2015) Acres, William. Objet de vertu: Euler's image and the circulation of genius in print, 1740-60. 2011 ____________. A "religious" model for history: John Strype's Reformation, 1660-1735. 2014 ____________, and David Bellhouse. Illustrating Innovation: mathematical books and their frontispieces, 1650-1750. 2009 Aebel, Ian J. Illustrating America: John Ogilby and the geographies of empire in Restoration England. 2013 Agten, Els. Vernacular Bible translation in the Netherlands in the seventeenth century: the debates between Roman Catholic faction and the Jansenists. 2014 Ahokas, Minna. Book history meets history of concepts: approaches to the books of the Enlightenment in eighteenth-century Finland. -

Front Matter Revised

Authorial or Scribal? : spelling variation in the Hengwrt and Ellesmere manuscripts of The Canterbury Tales Caon, L.M.D. Citation Caon, L. M. D. (2009, January 14). Authorial or Scribal? : spelling variation in the Hengwrt and Ellesmere manuscripts of The Canterbury Tales. LOT, Utrecht. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/13402 Version: Corrected Publisher’s Version Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/13402 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). References Baker, Donald C. (ed.) (1984), A Variorum Edition of the Works of Geoffrey Chaucer , vol. II, The Canterbury Tales, part 10, The Manciple Tale , Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. Barbrook, A., Christopher J. Howe, Norman Blake, Peter Robinson (1998), ‘The Phylogeny of The Canterbury Tales ’, Nature , 394, 839. Benskin, Michael and Margaret Laing (1981), ‘Translations and Mischsprachen in Middle English Manuscripts’, in M. Benskin and M.L. Samuels (eds), So Meny People Longages and Tonges: Philological Essays in Scots and Medieval English presented to Angus McIntosh , Edinburgh: Edinburgh Middle English Dialect Project, 55–106. Benson, Larry D. (ed.) (1987), The Riverside Chaucer , 3rd edn, Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Benson, Larry D. (1992), ‘Chaucer’s Spelling Reconsidered’, English Manuscript Studies 1100 –1700 3: 1–28. Reprinted in T.M. Andersson and S.A. Barney (eds) (1995) Contradictions: From Beowulf to Chaucer , Aldershot: Scolar Press. Blake, Norman F. (ed.) (1980), The Canterbury Tales. Edited from the Henwgrt Manuscript , London: Edward Arnold. Blake, Norman F. (1985), The Textual Tradition of The Canterbury Tales , London: Edward Arnold. -

The European English Messenger

The European English Messenger Volume 21.2 – Winter 2012 Contents ESSE MATTERS 3 - Fernando Galván, The ESSE President’s Column 7 - Marina Dossena, Editorial Notes and Password 8 - Jacques Ramel, ‘Like’ the ESSE Facebook page 9 - Liliane Louvel is the new ESSE President 11 - Hortensia Pârlog is the new Editor of the European English Messenger 12 - ESSE Book Awards 2012 - ESSE Bursaries for 2013 15 - Laurence Lux-Sterritt, Doing research in the UK – on an ESSE bursary 17 - Call for applications and nominations (ESSE Secretary and Treasurer) 19 - European Journal of English Studies 20 - ESSE 12, Košice 2014 22 - Graham Caie, In memoriam : Norman Blake 24 RESEARCH - Ben Parsons, The Fall of Princes and Lydgate’s knowledge 26 of The Book of the Duchess - Jonathan P. A. Sell, The Place of English Literary Studies in the Dickens of a Crisis 31 REPORTS AND REVIEWS 36 Christoph Henke, Daniela Landert, Virginia Pulcini, Annika McPherson, Nicholas Brownlees, Dirk Schultze, Annelie Ädel, Risto Hiltunen, Iman M. Laversuch, Jessica Aliaga Lavrijsen, Judit Mudriczki, Marc C. Conner, Eoghan Smith, Onno Kosters, Elena Voj , José-Carlos Redondo-Olmedilla, Miles Leeson, Balz Engler, John Miller, Erik Martiny, Stavros Stavrou Karayanni, Mark Sullivan, Paola Di Gennaro, Benjamin Keatinge 95 ANNOUNCEMENTS FROM THE ASSOCIATIONS 96 ESSE BOARD MEMBERS: NATIONAL REPRESENTATIVES The European English Messenger, 21.2 (2012) Professor Fernando Galván’s Honorary Degree at the University of Glasgow, 13 June 2012 (in this photo, from left to right: Fernando Galván, Ann Caie, Graham Caie, Hortensia Pârlog, Lachlan Mackenzie and Slavka Tomaščiková) 2 The European English Messenger, 21.2 (2012) ______________________________________________________________________________ The ESSE President’s Column Fernando Galván _______________________________________________________________________________ Some weeks after the ESSE-11 Conference in Istanbul of 4-8 September, I still have very vivid memories of a fantastic city and a highly successful academic gathering. -

Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected]

Marshall University Marshall Digital Scholar Theses, Dissertations and Capstones 2016 Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal Danielle Van Oort [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://mds.marshall.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Religion Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Van Oort, Danielle, "Rest, Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal" (2016). Theses, Dissertations and Capstones. Paper 1016. This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Marshall Digital Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses, Dissertations and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Marshall Digital Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. REST, SWEET NYMPHS: PASTORAL ORIGINS OF THE ENGLISH MADRIGAL A thesis submitted to the Graduate College of Marshall University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Music Music History and Literature by Danielle Van Oort Approved by Dr. Vicki Stroeher, Committee Chairperson Dr. Ann Bingham Dr. Terry Dean, Indiana State University Marshall University May 2016 APPROVAL OF THESIS We, the faculty supervising the work of Danielle Van Oort, affirm that the thesis, Rest Sweet Nymphs: Pastoral Origins of the English Madrigal, meets the high academic standards for original scholarship and creative work established by the School of Music and Theatre and the College of Arts and Media. This work also conforms to the editorial standards of our discipline and the Graduate College of Marshall University. With our signatures, we approve the manuscript for publication. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The author would like to express appreciation and gratitude to the faculty and staff of Marshall University’s School of Music and Theatre for their continued support. -

Chaucer and Bawdy

Chaucer and Bawdy G. R. Simes RANCE. Had you committed the act you wouldn't now be facing the charge. PRENTICE. I couldn't commit the act. I'm a heterosexual. RANCE. I wish you wouldn't use these Chaucerian words. It's most confusing. Joe Onon, What the Butler Saw (1969), p. 55. The reputation of a medieval poet is such that a successful dramatist of the 1960s could rely on the mere mention of his name to convey to the audience of the play the ideas of naughtiness and bawdy. Presumably the expansion of senior-secondary and tertiary education after World War II, the gradual relaxation of sexual mores, and the ready availability of a lively translation of the Canterbury Tales had all been factors_ that contributed to a popular dissemination of Chaucer's reputation for bawdiness. If that is so, it occurred in the absence of scholarly activity and interest in the topic. It is true that Chaucer shares with Shakespeare the singular honour of having a book devoted to his bawdy; yet that book was published as recently as 1972 and, modelling itself on Partridge's pioneering work on Shakespeare, takes the form of discursive glosses, apart from a brief, conceptually uncritical introduction. I In general, before the later 1960s, while many medievalists privately took pleasure in Chaucer's treatment of sexual and excretory matters, they did not write upon this aspect of his work with the same unembarrassed candour that the poet himself had shown. Among general readers this aspect of Chaucer, and to an extent Chaucer's very name, was very often an occasion for sniggering. -

Evolution and Ambition in the Career of Jan Lievens (1607-1674)

ABSTRACT Title: EVOLUTION AND AMBITION IN THE CAREER OF JAN LIEVENS (1607-1674) Lloyd DeWitt, Ph.D., 2006 Directed By: Prof. Arthur K. Wheelock, Jr. Department of Art History and Archaeology The Dutch artist Jan Lievens (1607-1674) was viewed by his contemporaries as one of the most important artists of his age. Ambitious and self-confident, Lievens assimilated leading trends from Haarlem, Utrecht and Antwerp into a bold and monumental style that he refined during the late 1620s through close artistic interaction with Rembrandt van Rijn in Leiden, climaxing in a competition for a court commission. Lievens’s early Job on the Dung Heap and Raising of Lazarus demonstrate his careful adaptation of style and iconography to both theological and political conditions of his time. This much-discussed phase of Lievens’s life came to an end in 1631when Rembrandt left Leiden. Around 1631-1632 Lievens was transformed by his encounter with Anthony van Dyck, and his ambition to be a court artist led him to follow Van Dyck to London in the spring of 1632. His output of independent works in London was modest and entirely connected to Van Dyck and the English court, thus Lievens almost certainly worked in Van Dyck’s studio. In 1635, Lievens moved to Antwerp and returned to history painting, executing commissions for the Jesuits, and he also broadened his artistic vocabulary by mastering woodcut prints and landscape paintings. After a short and successful stay in Leiden in 1639, Lievens moved to Amsterdam permanently in 1644, and from 1648 until the end of his career was engaged in a string of important and prestigious civic and princely commissions in which he continued to demonstrate his aptitude for adapting to and assimilating the most current style of his day to his own somber monumentality. -

HNA April 11 Cover-Final.Indd

historians of netherlandish art NEWSLETTER AND REVIEW OF BOOKS Dedicated to the Study of Netherlandish, German and Franco-Flemish Art and Architecture, 1350-1750 Vol. 28, No. 1 April 2011 Jacob Cats (1741-1799), Summer Landscape, pen and brown ink and wash, 270-359 mm. Hamburger Kunsthalle. Photo: Christoph Irrgang Exhibited in “Bruegel, Rembrandt & Co. Niederländische Zeichnungen 1450-1850”, June 17 – September 11, 2011, on the occasion of the publication of Annemarie Stefes, Niederländische Zeichnungen 1450-1850, Kupferstichkabinett der Hamburger Kunsthalle (see under New Titles) HNA Newsletter, Vol. 23, No. 2, November 2006 1 historians of netherlandish art 23 S. Adelaide Avenue, Highland Park, NJ 08904 Telephone/Fax: (732) 937-8394 E-Mail: [email protected] www.hnanews.org Historians of Netherlandish Art Offi cers President - Stephanie Dickey (2009–2013) Bader Chair in Northern Baroque Art Queen’s University Kingston ON K7L 3N6 Canada Vice-President - Amy Golahny (2009–2013) Lycoming College Williamsport, PA 17701 Treasurer - Rebecca Brienen University of Miami Art & Art History Department PO Box 248106 Coral Gables FL 33124-2618 European Treasurer and Liaison - Fiona Healy Seminarstrasse 7 D-55127 Mainz Germany Board Members Contents Dagmar Eichberger (2008–2012) HNA News ............................................................................1 Wayne Franits (2009–2013) Matt Kavaler (2008–2012) Personalia ............................................................................... 2 Henry Luttikhuizen (2009 and 2010–2014) Exhibitions -

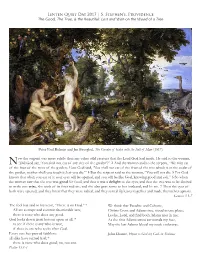

Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel, the Garden of Eden with the Fall of Man (1617)

Lenten Quiet Day 2017 | S. Stephen’s, Providence The Good, The True, & the Beautiful: Lost and Won on the Wood of a Tree Peter Paul Rubens and Jan Brueghel, The Garden of Eden with the Fall of Man (1617) ow the serpent was more subtle than any other wild creature that the Lord God had made. He said to the woman, N“Did God say, ‘You shall not eat of any tree of the garden’?” 2 And the woman said to the serpent, “We may eat of the fruit of the trees of the garden; 3 but God said, ‘You shall not eat of the fruit of the tree which is in the midst of the garden, neither shall you touch it, lest you die.’” 4 But the serpent said to the woman, “You will not die. 5 For God knows that when you eat of it your eyes will be opened, and you will be like God, knowing good and evil.” 6 So when the woman saw that the tree was good for food, and that it was a delight to the eyes, and that the tree was to be desired to make one wise, she took of its fruit and ate; and she also gave some to her husband, and he ate. 7 Then the eyes of both were opened, and they knew that they were naked; and they sewed fig leaves together and made themselves aprons. Genesis 3.1-7 The fool has said in his heart, “There is no God.” * We think that Paradise and Calvarie, All are corrupt and commit abominable acts; Christs Cross and Adams tree, stood in one place; there is none who does any good. -

Julius S. Held Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3g50355c No online items Finding aid for the Julius S. Held papers, ca. 1921-1999 Isabella Zuralski. Finding aid for the Julius S. Held 990056 1 papers, ca. 1921-1999 Descriptive Summary Title: Julius S. Held papers Date (inclusive): ca. 1918-1999 Number: 990056 Creator/Collector: Held, Julius S (Julius Samuel) Physical Description: 168 box(es)(ca. 70 lin. ft.) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Research papers of Julius Samuel Held, American art historian renowned for his scholarship in 16th- and 17th-century Dutch and Flemish art, expert on Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. The ca. 70 linear feet of material, dating from the mid-1920s to 1999, includes correspondence, research material for Held's writings and his teaching and lecturing activities, with extensive travel notes. Well documented is Held's advisory role in building the collection of the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico. A significant portion of the ca. 29 linear feet of study photographs documents Flemish and Dutch artists from the 15th to the 17th century. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical / Historical Note The art historian Julius Samuel Held is considered one of the foremost authorities on the works of Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. -

TIME IMAGERY H SHAKESPEARE's PLAYS and POEMS by Arthur T. Grant a Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of English I

Time imagery in Shakespeare's plays and poems Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Grant, Arthur T. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 23/09/2021 12:08:25 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/566674 TIME IMAGERY H SHAKESPEARE'S PLAYS AND POEMS by Arthur T. Grant A Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Department of English in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Graduate College, University of Arizona 1952 Director of Thesis ( 9 7 9 / ' A 8- ■ TABLE OF COITEM'S m p f i R PAOE i. 33^DE©BTJCHOE , , , , , @ a , o o , , , & , , , , o @ , » * © I Fl23?POS© of0 "feL,© 000000ijL©SlS000:0 0 0 000I 0 , 0000B©T IL3sl3»^ 3.0IX Of 0t©3nH8 0000 0,00 0I 0 0 000 Advantages of the study , o « , , , o , , , © . = « . « o 1 gamzat ion © , ,. , ,. ,■ , o , o , © o o , , , o , o , 2 H o A REVIEW OF m m TREM3S H HiAGERY STUDY i 3 ly stfGd.3—es , , , , , , , o o o © o , , © © © © © o © © 3 The xntrosfective approach © © © © © © . © © © . © © © o 5 The Organic approach © © © © © © © © © © © © © » © © © ©, 9 The substantiation method © © , © © , © © © , © © © © © © 9 Summary © & © © © © © © © © © © © o © © © © © © © © o © © H , HI, A TMS AlID I#IP HOD S © © o © © © © © , © © © © © © © © © © © © © 12 Mature of the investigation . © © © © © © © © © © © © . © 12 Advantages of the investigation , , , © , © © © © © © © © 12 Disadvantages of the investigation © © © © © © © © © © © 14 Befinition of an image © © © © © © © © © © © , © © © © » 1% Method of gathering images , © © .