Canterbury Tales" 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Front Matter Revised

Authorial or Scribal? : spelling variation in the Hengwrt and Ellesmere manuscripts of The Canterbury Tales Caon, L.M.D. Citation Caon, L. M. D. (2009, January 14). Authorial or Scribal? : spelling variation in the Hengwrt and Ellesmere manuscripts of The Canterbury Tales. LOT, Utrecht. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/13402 Version: Corrected Publisher’s Version Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/13402 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). References Baker, Donald C. (ed.) (1984), A Variorum Edition of the Works of Geoffrey Chaucer , vol. II, The Canterbury Tales, part 10, The Manciple Tale , Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. Barbrook, A., Christopher J. Howe, Norman Blake, Peter Robinson (1998), ‘The Phylogeny of The Canterbury Tales ’, Nature , 394, 839. Benskin, Michael and Margaret Laing (1981), ‘Translations and Mischsprachen in Middle English Manuscripts’, in M. Benskin and M.L. Samuels (eds), So Meny People Longages and Tonges: Philological Essays in Scots and Medieval English presented to Angus McIntosh , Edinburgh: Edinburgh Middle English Dialect Project, 55–106. Benson, Larry D. (ed.) (1987), The Riverside Chaucer , 3rd edn, Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Benson, Larry D. (1992), ‘Chaucer’s Spelling Reconsidered’, English Manuscript Studies 1100 –1700 3: 1–28. Reprinted in T.M. Andersson and S.A. Barney (eds) (1995) Contradictions: From Beowulf to Chaucer , Aldershot: Scolar Press. Blake, Norman F. (ed.) (1980), The Canterbury Tales. Edited from the Henwgrt Manuscript , London: Edward Arnold. Blake, Norman F. (1985), The Textual Tradition of The Canterbury Tales , London: Edward Arnold. -

The European English Messenger

The European English Messenger Volume 21.2 – Winter 2012 Contents ESSE MATTERS 3 - Fernando Galván, The ESSE President’s Column 7 - Marina Dossena, Editorial Notes and Password 8 - Jacques Ramel, ‘Like’ the ESSE Facebook page 9 - Liliane Louvel is the new ESSE President 11 - Hortensia Pârlog is the new Editor of the European English Messenger 12 - ESSE Book Awards 2012 - ESSE Bursaries for 2013 15 - Laurence Lux-Sterritt, Doing research in the UK – on an ESSE bursary 17 - Call for applications and nominations (ESSE Secretary and Treasurer) 19 - European Journal of English Studies 20 - ESSE 12, Košice 2014 22 - Graham Caie, In memoriam : Norman Blake 24 RESEARCH - Ben Parsons, The Fall of Princes and Lydgate’s knowledge 26 of The Book of the Duchess - Jonathan P. A. Sell, The Place of English Literary Studies in the Dickens of a Crisis 31 REPORTS AND REVIEWS 36 Christoph Henke, Daniela Landert, Virginia Pulcini, Annika McPherson, Nicholas Brownlees, Dirk Schultze, Annelie Ädel, Risto Hiltunen, Iman M. Laversuch, Jessica Aliaga Lavrijsen, Judit Mudriczki, Marc C. Conner, Eoghan Smith, Onno Kosters, Elena Voj , José-Carlos Redondo-Olmedilla, Miles Leeson, Balz Engler, John Miller, Erik Martiny, Stavros Stavrou Karayanni, Mark Sullivan, Paola Di Gennaro, Benjamin Keatinge 95 ANNOUNCEMENTS FROM THE ASSOCIATIONS 96 ESSE BOARD MEMBERS: NATIONAL REPRESENTATIVES The European English Messenger, 21.2 (2012) Professor Fernando Galván’s Honorary Degree at the University of Glasgow, 13 June 2012 (in this photo, from left to right: Fernando Galván, Ann Caie, Graham Caie, Hortensia Pârlog, Lachlan Mackenzie and Slavka Tomaščiková) 2 The European English Messenger, 21.2 (2012) ______________________________________________________________________________ The ESSE President’s Column Fernando Galván _______________________________________________________________________________ Some weeks after the ESSE-11 Conference in Istanbul of 4-8 September, I still have very vivid memories of a fantastic city and a highly successful academic gathering. -

HOGG, Richard (General Ed.): the Cambridge History of the English Lan- Guage

HOGG, Richard (General Ed.): The Cambridge History of the English Lan- guage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Volume I: The Be- ginnings to 1066. Edited by Richard M. Hogg (1992). xxii + 609 pp. (£60.00). Volume II: 1066-1476. Edited by Norman Blake (1992). xxi + 703 pp. (£ 65.00). Writing a review on a major work such as this one -namely "the first multi- volume work to provide a full account of the history of English" (Presentation) is a task which remains necessarily incomplete. This is so for two obvious reasons: one, only the first two volumes are available; two, each chapter is worth reviewing in itself, for reasons that will become evident in what follows. Any overall judgement must wait then till the complete series is pub- lished; even so, these two books contain sufficient elements to predict a sucessful result for a most ambitious project. And project is really the key word: it has been carefully planned and scheduled from the very beginning as is shown by the detailed contents of all the forthcoming volumes. But as a matter of fact, this was only to be expected from the General Editor, who, besides his well known perceptiveness, expertise, and insightful knowledge, has added to the assets of this work Volume Editors and contributors such as Norman Blake, Roger Lass, John Algeo, Vivian Salmon, Cecily Clark, Malcolm Godden, Elizabeth Closs Traugott, Manfred Görlach, Matti Rissanen, Dieter Kastovsky, John Wells, James Milroy, David Burnley, Braj Kachru, Suzanne Romaine, Robert Burchfield, Dennis Baron, David Denison... to mention just a few. Together with the advisors appearing in the Acknowledgements (f.i. -

The Emergence of Standard English

University of Kentucky UKnowledge English Language English Language and Literature 10-19-1995 The Emergence of Standard English John H. Fisher Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Fisher, John H., "The Emergence of Standard English" (1995). English Language. 1. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_english_language_and_literature/1 THE EMERGENCE OF STANDARD ENGLISH THE EMERGENCE OF ~t STANDARD ENGLISH~- ..., h t\( ~· '1~,- ~· n~· John H. Fisher Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright© 1996 by The University Press of Kentucky The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Fuson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Fisher, John H. The emergence of standard English I John H. Fisher. p. em. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN Q-8131-1935-9 (cloth : alk. -

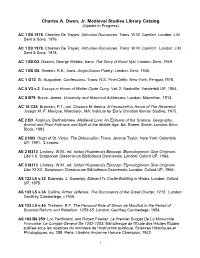

Charles A. Owen, Jr. Medieval Studies Library Catalog (Update in Progress)

Charles A. Owen, Jr. Medieval Studies Library Catalog (Update in Progress) AC 1 E8 1976 Chretien De Troyes. Arthurian Romances. Trans. W.W. Comfort. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1976. AC 1 E8 1978 Chretien De Troyes. Arthurian Romances. Trans. W.W. Comfort. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1978. AC 1 E8 D3 Dasent, George Webbe, trans. The Story of Burnt Njal. London: Dent, 1949. AC 1 E8 G6 Gordon, R.K., trans. Anglo-Saxon Poetry. London: Dent, 1936. AC 1 G72 St. Augustine. Confessions. Trans. R.S. Pine-Coffin. New York: Penguin,1978. AC 5 V3 v.2 Essays in Honor of Walter Clyde Curry. Vol. 2. Nashville: Vanderbilt UP, 1954. AC 8 B79 Bryce, James. University and Historical Addresses. London: Macmillan, 1913. AC 15 C55 Brannan, P.T., ed. Classica Et Iberica: A Festschrift in Honor of The Reverend Joseph M.-F. Marique. Worcester, MA: Institute for Early Christian Iberian Studies, 1975. AE 2 B3 Anglicus, Bartholomew. Medieval Lore: An Epitome of the Science, Geography, Animal and Plant Folk-lore and Myth of the Middle Age. Ed. Robert Steele. London: Elliot Stock, 1893. AE 2 H83 Hugh of St. Victor. The Didascalion. Trans. Jerome Taylor. New York: Columbia UP, 1991. 2 copies. AE 2 I8313 Lindsay, W.M., ed. Isidori Hispalensis Episcopi: Etymologiarum Sive Originum. Libri I-X. Scriptorum Classicorum Bibliotheca Oxoniensis. London: Oxford UP, 1966. AE 2 I8313 Lindsay, W.M., ed. Isidori Hispalensis Episcopi: Etymologiarum Sive Originum. Libri XI-XX. Scriptorum Classicorum Bibliotheca Oxoniensis. London: Oxford UP, 1966. AS 122 L5 v.32 Edwards, J. Goronwy. -

Missouri Folklore Society Journal

Missouri Folklore Society Journal Special Issue: Songs and Ballads Volumes 27 - 28 2005 - 2006 Cover illustration: Anonymous 19th-century woodcut used by designer Mia Tea for the cover of a CD titled Folk Songs & Ballads by Mark T. Permission for MFS to use a modified version of the image for the cover of this journal was granted by Circle of Sound Folk and Community Music Projects. The Mia Tea version of the woodcut is available at http://www.circleofsound.co.uk; acc. 6/6/15. Missouri Folklore Society Journal Volumes 27 - 28 2005 - 2006 Special Issue Editor Lyn Wolz University of Kansas Assistant Editor Elizabeth Freise University of Kansas General Editors Dr. Jim Vandergriff (Ret.) Dr. Donna Jurich University of Arizona Review Editor Dr. Jim Vandergriff Missouri Folklore Society P. O. Box 1757 Columbia, MO 65205 This issue of the Missouri Folklore Society Journal was published by Naciketas Press, 715 E. McPherson, Kirksville, Missouri, 63501 ISSN: 0731-2946; ISBN: 978-1-936135-17-2 (1-936135-17-5) The Missouri Folklore Society Journal is indexed in: The Hathi Trust Digital Library Vols. 4-24, 26; 1982-2002, 2004 Essentially acts as an online keyword indexing tool; only allows users to search by keyword and only within one year of the journal at a time. The result is a list of page numbers where the search words appear. No abstracts or full-text incl. (Available free at http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Search/Advanced). The MLA International Bibliography Vols. 1-26, 1979-2004 Searchable by keyword, author, and journal title. The result is a list of article citations; it does not include abstracts or full-text. -

The Northern/Scottish Dialect in Nathaniel Woodes' A

The Northern/Scottish Dialect in Nathaniel Woodes’ A Conflict of Conscience (1581)1 María Fuencisla García-Bermejo Giner UNIVERSIDAD DE SALAMANCA [email protected] 1. INTRODUCTION. Varieties of English other than the ‘standard’ were frequent in 16th-c. literature, in poems and jest books and also in fiction2 and in drama. Since the days of Chaucer and the Wakefield Master, when literary dialects started to be used as a means of characterization, this device had generally become a way to signal the rusticity and comicity of characters. Not all varieties had the same function or status. Whereas southwestern traits had come to be associated with comic country bumpkins, whatever their origins, Irish with wild characters and Welsh with foolish, Northern and Scottish features were not always only used for comedy.3 In moralities and interludes and in the Renaissance drama Northern and Scottish traits were combined in the speeches of characters specifically nationalized as Scots or Northern. From a linguistic point of view these two varieties were also more carefully represented than others although most audiences would have been unable to distinguish between them. Blank (1996: 108) shows that the attitudes towards Northern English differed from those towards the other varieties and were ambivalent: “At once the rude dialect of ploughmen and an ancestral English, the Northern dialect was prosecuted as provincial and defended as the wellspring of the national language”. As years went by and almost up to the last century, all these stage characters became highly conventionalized and so did the linguistic features given to them. Nevertheless, it seems plausible that, at least in the initial stages, some of these regional traits actually reflected current usage. -

Ÿþm I C R O S O F T W O R

Leeds Studies in English Article: Lesley Johnson, 'Tracking Layamon's Brut', Leeds Studies in English, n.s. 22, (1991), 139-65 Permanent URL: https://ludos.leeds.ac.uk:443/R/-?func=dbin-jump- full&object_id=121849&silo_library=GEN01 Leeds Studies in English School of English University of Leeds http://www.leeds.ac.uk/lse Tracking La3amon's Brut1 Lesley Johnson The modern study of L^amon's Brut would seem to have had a highly propitious start with the publication of Sir Frederic Madden's three volume edition of La3amon's work, for the Society of Antiquaries, in 1847.2 Madden's edition, with its parallel text from the two extant manuscript copies of the Brut, its extensive notes, glossary, and running modernisation of the narrative at the foot of every page, made a work that had previously attracted only intermittent scholarly interest accessible to an audience of specialists and non-specialists alike.3 After 1847, it would seem, La3amon's Brut was readable, literally, once more. Indeed one tangible effect of Madden's act of retrieval can be traced in the text of Tennyson's Idylls of the King: echoes of La3amon's version of Arthurian history (or rather of Madden's running gloss on La3amon's text) are woven into the sequence, particularly in the opening and closing frames where some archaic resonance is sought by Tennyson.4 Madden's work may also have stimulated a rather more local effort to commemorate La3amon: in J. S. P. Tatlock's view, the inscription on the (older) base of the modem font at Areley Kings in Worcestershire which appears to refer to 'St La3amon' is a later nineteenth-century forgery which was designed to secure La3amon ('who was very little known before Madden's edition of 1847') as a local worthy.5 Yet, this propitious start has not resulted in La3amon's literary canonisation. -

2016 Ainsworth Breeman Diss

UNIVERSITY OF OKLAHOMA GRADUATE COLLEGE NATION AND COMPILATION IN ENGLAND, 1270-1500 A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE FACULTY in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By BREEMAN AINSWORTH Norman, Oklahoma 2016 NATION AND COMPILATION IN ENGLAND, 1270-1500 A DISSERTATION APPROVED FOR THE DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH BY ______________________________ Dr. Kenneth Hodges, Chair ______________________________ Dr. Daniel Ransom ______________________________ Dr. Su Fang Ng ______________________________ Dr. Jennifer Saltzstein ______________________________ Dr. Logan Whalen © Copyright by BREEMAN AINSWORTH 2016 All Rights Reserved. For Melissa and Isabella Acknowledgements This project began as a footnote in a paper for Literary Theory, and as you might imagine from such humble origins, the path to this dissertation has been long. The final result bears little resemblance to where I thought I was going at the start of my studies. Its completion is thanks to many individuals who challenged and supported me in the process. In the limited space here, I cannot thank the many people who supported and nurtured this project. First and foremost, I must thank my wife Melissa and my daughter Isabella. Without their patience, sacrifice, and support on a daily level, this project would have never been completed. I hope what follows is worthy of your contributions. Second, I must thank my Chair Kenneth Hodges. Professor Hodges brought an energy and enthusiasm to this project, which even I—at times— began to doubt. He challenged me to consider new methods of arranging material in order to draw out the best argument. His incisive comments on the project have improved it greatly. -

Firstpersonsingular.Pdf

FROM ENGLISH PHILOLOGY TO LINGUISTICS AND BACK AGAIN ROBERT P. STOCKWELL University of California, Los Angeles This is an offprint from: E.F.K. Koerner (ed.) First Person Singular III. Autobiographies by North American scholars in the language sciences. John Benjamins Publishing Company AmsterdamlPhiladelphia 1998 (Published as Vol. 88 ofthe series STUDIES IN THE mSTORY OF THE LANGUAGE SCIENCES, ISSN 0304-0720) ISBN 90 272 4576 2 (Hb; Eur.) / I 556196326 (Hb; US) © Copyright 1998 - John Benjamins B.V. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm or any other means, without written pennission from the publisher. FROM ENGLISH PHILOLOGY TO LINGUISTICS AND BACIK AGAIN ROBERT P. STOCKWELL University o/California, Los Angeles If you spent your formative years in Charleston, West Virginia, in the late 1930s and early 1940s thinking you wanted to be a professional musician of some sort, you didn't have much of a chance. There was a symphony, not a very good one but the only one, and I played first flute in it throughout my junior high and high school years. That's because the only better flutist lived 50 miles away. in Hurttington, and that was a long ways to go in those days with no super-highways along the river, for an orchestra rehearsal Of perfor mance. If I had had good sense, or good advice, I wonld have taken up 'cello then rather than waiting until I was 45 to finally learn what is special about string chamber music, but way too late for me to get good at it. -

An Analysis of Personal Pronouns in Middle English Literary Texts

Eastern Illinois University The Keep Masters Theses Student Theses & Publications 1995 An Analysis of Personal Pronouns in Middle English Literary Texts Melissa Jill Bennett This research is a product of the graduate program in English at Eastern Illinois University. Find out more about the program. Recommended Citation Bennett, Melissa Jill, "An Analysis of Personal Pronouns in Middle English Literary Texts" (1995). Masters Theses. 2125. https://thekeep.eiu.edu/theses/2125 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Theses & Publications at The Keep. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses by an authorized administrator of The Keep. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THESIS REPRODUCTION CERTIFICATE TO: Graduate Degree Candidates (who have written formal theses) SUBJECT: Permission to Reproduce Theses The University Library is rece1v1ng a number of requests from other institutions asking permission to reproduce dissertations for inclu$ion in their library holdings. Although no copyright laws are involved, we feel that professional courtesy demands that permission be obtained from the author before we allow theses to be copied. PLEASE.SIGN ONE OF THE FOLLOWING STATEMENTS: Booth library of Eastern Illinois University has my permission to lend my thesis to a reputable college or university for the purpose of copying it for inclusion in that institution's library or research holdings. Date I respectfully request Booth Library of Eastern Illinois University not allow my thesis to be reproduced -

Chaucerian Works in the English Renaissance: Editions and Imitations

THE CATHOLIC UNIVERSITY OF AMERICA Chaucerian Works in the English Renaissance: Editions and Imitations A DISSERTATION Submitted to the Faculty of the Department of English School of Arts and Sciences Of The Catholic University of America In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy By Sean Gordon Lewis Washington, D.C. 2011 Chaucerian Works in the English Renaissance: Editions and Imitations Sean Gordon Lewis, Ph.D. Director: Michael Mack, Ph.D. Chaucerian Works in the English Renaissance: Editions and Imitations articulates the connection between editorial presentation and authorial imitation in order to solve a very specific problem: why were the comedic aspects of the works of Geoffrey Chaucer—aspects that appear to be central to his poetic sensibilities—so often ignored by Renaissance poets who drew on Chaucerian materials? While shifts in language, religion, politics, and poetic sensibilities help account for a predilection for prizing Chaucerian works of sentence (moral gravity), it does not adequately explain why a poet like Edmund Spenser—one of the age’s most unabashedly Chaucerian poets—would imitate comedic, works of solaas (literary pleasure) in a completely sententious manner. This dissertation combines bibliographic approaches with formal analysis of literary history, leading to a fuller understanding of the “uncomedying” of Chaucer by Renaissance editors and poets. This dissertation examines the rhetorical and aesthetic effects of editions of the works of Chaucer published between 1477 and 1602 (Caxton through Speght) as a means of understanding patterns of Chaucerian imitation by poets of the period. Although the most obvious shift in textual presentation is the change from printing single works to printing “Complete Works” beginning with the 1532 Thynne, I argue that choices made by the printing-house (in terms of layout, font, and, most specifically, editorial directions) had a gradual, cumulative effect of highlighting Chaucerian sentence at the expense of solaas .