"Fer in the North; I Kan Nat Telle Where": Dialect, Regionalism, and Philologism

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Front Matter Revised

Authorial or Scribal? : spelling variation in the Hengwrt and Ellesmere manuscripts of The Canterbury Tales Caon, L.M.D. Citation Caon, L. M. D. (2009, January 14). Authorial or Scribal? : spelling variation in the Hengwrt and Ellesmere manuscripts of The Canterbury Tales. LOT, Utrecht. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/13402 Version: Corrected Publisher’s Version Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/13402 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). References Baker, Donald C. (ed.) (1984), A Variorum Edition of the Works of Geoffrey Chaucer , vol. II, The Canterbury Tales, part 10, The Manciple Tale , Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. Barbrook, A., Christopher J. Howe, Norman Blake, Peter Robinson (1998), ‘The Phylogeny of The Canterbury Tales ’, Nature , 394, 839. Benskin, Michael and Margaret Laing (1981), ‘Translations and Mischsprachen in Middle English Manuscripts’, in M. Benskin and M.L. Samuels (eds), So Meny People Longages and Tonges: Philological Essays in Scots and Medieval English presented to Angus McIntosh , Edinburgh: Edinburgh Middle English Dialect Project, 55–106. Benson, Larry D. (ed.) (1987), The Riverside Chaucer , 3rd edn, Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Benson, Larry D. (1992), ‘Chaucer’s Spelling Reconsidered’, English Manuscript Studies 1100 –1700 3: 1–28. Reprinted in T.M. Andersson and S.A. Barney (eds) (1995) Contradictions: From Beowulf to Chaucer , Aldershot: Scolar Press. Blake, Norman F. (ed.) (1980), The Canterbury Tales. Edited from the Henwgrt Manuscript , London: Edward Arnold. Blake, Norman F. (1985), The Textual Tradition of The Canterbury Tales , London: Edward Arnold. -

The European English Messenger

The European English Messenger Volume 21.2 – Winter 2012 Contents ESSE MATTERS 3 - Fernando Galván, The ESSE President’s Column 7 - Marina Dossena, Editorial Notes and Password 8 - Jacques Ramel, ‘Like’ the ESSE Facebook page 9 - Liliane Louvel is the new ESSE President 11 - Hortensia Pârlog is the new Editor of the European English Messenger 12 - ESSE Book Awards 2012 - ESSE Bursaries for 2013 15 - Laurence Lux-Sterritt, Doing research in the UK – on an ESSE bursary 17 - Call for applications and nominations (ESSE Secretary and Treasurer) 19 - European Journal of English Studies 20 - ESSE 12, Košice 2014 22 - Graham Caie, In memoriam : Norman Blake 24 RESEARCH - Ben Parsons, The Fall of Princes and Lydgate’s knowledge 26 of The Book of the Duchess - Jonathan P. A. Sell, The Place of English Literary Studies in the Dickens of a Crisis 31 REPORTS AND REVIEWS 36 Christoph Henke, Daniela Landert, Virginia Pulcini, Annika McPherson, Nicholas Brownlees, Dirk Schultze, Annelie Ädel, Risto Hiltunen, Iman M. Laversuch, Jessica Aliaga Lavrijsen, Judit Mudriczki, Marc C. Conner, Eoghan Smith, Onno Kosters, Elena Voj , José-Carlos Redondo-Olmedilla, Miles Leeson, Balz Engler, John Miller, Erik Martiny, Stavros Stavrou Karayanni, Mark Sullivan, Paola Di Gennaro, Benjamin Keatinge 95 ANNOUNCEMENTS FROM THE ASSOCIATIONS 96 ESSE BOARD MEMBERS: NATIONAL REPRESENTATIVES The European English Messenger, 21.2 (2012) Professor Fernando Galván’s Honorary Degree at the University of Glasgow, 13 June 2012 (in this photo, from left to right: Fernando Galván, Ann Caie, Graham Caie, Hortensia Pârlog, Lachlan Mackenzie and Slavka Tomaščiková) 2 The European English Messenger, 21.2 (2012) ______________________________________________________________________________ The ESSE President’s Column Fernando Galván _______________________________________________________________________________ Some weeks after the ESSE-11 Conference in Istanbul of 4-8 September, I still have very vivid memories of a fantastic city and a highly successful academic gathering. -

With Dialect It's Not What You

26 MONDAY, MAY 25, 2015 Eastern Daily Press Like us at: OPINION and comment www.facebook.com/edp24 Eastern Daily Press READER’S PICTURE OF THE DAY SERVING THE COMMUNITY SINCE 1870 Enjoy this day City fans – it doesn’t come around very often Today’s the day. Thousands are deserting our region and heading for Wembley – 30 years since Norwich City last made an appearance there. Coaches, cars and trains will be packed with fans as they head for the traditional home of football and the dramatic sight of the arch which dominates the new stadium. A small army of loyal long-distance followers have jetted in from Canada, South Africa, Thailand, Australia, Vietnam, Hong Kong and Dubai to see the Canaries’ biggest game in decades. Many thousands more will be at home or in the pub watching the play-off final against Middlesbrough. The excitement has built up to fever pitch and nerves will be stretched to their limits as the team strives to regain its place in the Premier League. Middlesbrough have beaten Norwich in the league, but none of that will matter when the teams take to the pitch this afternoon. Experts estimate that promotion is worth as much as £130m to the club. For the fans there is the mouth-watering prospect of playing against some of the game’s biggest names. For the city and the region there is the extra morale boost and status attached to being in the top flight. I Val Bond sent in this colourful meadow in Gisleham. If you would like to submit a picture for possible publication in the EDP, visit www. -

Translating Sociolect in the Works of Charles Dickens Master’S Diploma Thesis

Masaryk University Faculty of Arts Department of English and American Studies English-language Translation Bc. Tereza Rotterová Translating Sociolect in the Works of Charles Dickens Master’s Diploma Thesis Supervisor: Ing. Mgr. Jiří Rambousek, Ph. D. 2017 I declare that I have worked on this thesis independently, using only the primary and secondary sources listed in the bibliography. …………………………………………….. Author’s signature I would like to thank my supervisor Ing. Mgr. Jiří Rambousek, Ph.D. for valuable advice. Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 5 1) THEORETICAL BACKGROUND FOR ANALYZING DIALECT IN TRANSLATION....................................................................................................................... 7 1.1 KEY TERMINOLOGY IN ANALYZING DIALECT TRANSLATION .................................... 7 1.2 THE NOTION OF STANDARD: CZECH AND ENGLISH ............................................... 10 1.2.1 THE NOTION OF STANDARD: ENGLISH ................................................................ 10 1.2.2 THE NOTION OF STANDARD: CZECH ................................................................... 13 1.3 STRUCTURAL DIFFERENCES BETWEEN ENGLISH AND CZECH ................................. 18 1.4 APPROACHES TO TRANSLATING DIALECT AND SOCIOLECT..................................... 19 2) DICKENS AND THE LITERARY DIALECT ....................................................... 24 3) METHODOLOGY OF RESEARCH ...................................................................... -

Canterbury Tales" 1

Bo/etíll Mí//ares Car/o ISSN: 0211-2140 1005-1006,14-25: 379-394 Orthography, Codicology, and Textual Studies: The Cambridge Un iversity Library, Gg.4.27 "Canterbury Tales" 1 Jacob TIIA1SEN Adam MickiewicL University SU:\lMARY An analysis 01' thc distrihution 01' orthographic variants in the Cambridge University Library, MS Gg.4.27 copy ofChauccr's CUlllahur\' Ta/es suggests that longer tranches ofthe source text were together, and partially ordered, already when it reached the scribe. The cvidencc 01' this manuscript's quiring, inks, miniatures, and ordinatio supports this finding. Studying linguistic and (other) codicological aspects 01' manuscripts may thus he 01' use to textual scholars and editors. Key words: Chaucer - Call1erhur\' Ta/cs - manuscript studies - Middle English - scribes - illu mination -- dialectology - graphemic and orthographic variation - textual studies RESUMEN El análisis de la distribución de las variantes gralcmicas en la copia de los ClIclllos dc Call1crhlllT de Chaucer en Cambridge University Lihrary, MS Gg.4.27 sugierc que fi'agmentos largos del texto ya estahan juntos y parcialmente ordenados cuando éste llego al escriba. Esta idea tamhién sc sustenta en evidencias paleográficas en el manuscrito, como las tintas, las miniaturas, los cuadernos, y la disposición en la página. El estudio de los aspectos lingüisticos y eodieológicos de los manusritos pueden serie úti les a editores y critieos textuales, Palabras clavc: Chaucer, Cllclllos dc Call1erhllr\,, manuscritos, inglés medio, escrihas, illumi nación, dialectología, variación gralcmica y ortográfica, estudios textuales INTRODUCTION The dialecto10gist Angus McIntosh has noted that one type of exemp1ar influenee has the interesting characteristic that "jt tends to assert itsc1f less and 1ess as the scribe proceeds with his work" (1975 [1989: 44 n. -

Opinion&Comment

20 OPINION www.EDP24.co.uk/news Eastern Daily Press, Wednesday, August 29, 2012 OPINION&COMMENT (DVWHUQ'DLO\3UHVV READER’S PICTURE OF THE DAY No 43,968 Plenty of stirrings in Conservative ranks Page Five A prime minister may cast aside attacks from the Opposition benches of the Commons with a show of strength and a flash of wit; but when the assault is from his own party, it is a different kettle of fish. In the next few weeks David Cameron will face several assaults from within his own ranks which will help clarify his chances of winning the next general election. Managing the politics of coalition with the Liberal Democrats, with whom relations have crashed over constitutional reform, must be sapping, even if Mr Cameron does get on well personally with their leader Nick Clegg – and there is a danger of it becoming a growing distraction from getting across the real policies and messages he wants people to listen to. Former minister Tim Yeo hardly held back yesterday when he challenged Mr Cameron to be “man or mouse” and spoke of a “dignified slide towards insignificance” with voters unable to see his priorities and passions. The context was a third Heathrow runway. The code was blatantly obvious. Mr Cameron’s dinner with parliamentary colleagues next week and William Hague’s appearance at the 1922 committee of Tory backbenchers are unlikely to be very comfortable. Rail fares, planning, Sunday trading laws, not to mention runways… Or even the coalition… Or Europe… Or the economy. There are plenty of stirrings in Conservative ranks. -

HOGG, Richard (General Ed.): the Cambridge History of the English Lan- Guage

HOGG, Richard (General Ed.): The Cambridge History of the English Lan- guage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Volume I: The Be- ginnings to 1066. Edited by Richard M. Hogg (1992). xxii + 609 pp. (£60.00). Volume II: 1066-1476. Edited by Norman Blake (1992). xxi + 703 pp. (£ 65.00). Writing a review on a major work such as this one -namely "the first multi- volume work to provide a full account of the history of English" (Presentation) is a task which remains necessarily incomplete. This is so for two obvious reasons: one, only the first two volumes are available; two, each chapter is worth reviewing in itself, for reasons that will become evident in what follows. Any overall judgement must wait then till the complete series is pub- lished; even so, these two books contain sufficient elements to predict a sucessful result for a most ambitious project. And project is really the key word: it has been carefully planned and scheduled from the very beginning as is shown by the detailed contents of all the forthcoming volumes. But as a matter of fact, this was only to be expected from the General Editor, who, besides his well known perceptiveness, expertise, and insightful knowledge, has added to the assets of this work Volume Editors and contributors such as Norman Blake, Roger Lass, John Algeo, Vivian Salmon, Cecily Clark, Malcolm Godden, Elizabeth Closs Traugott, Manfred Görlach, Matti Rissanen, Dieter Kastovsky, John Wells, James Milroy, David Burnley, Braj Kachru, Suzanne Romaine, Robert Burchfield, Dennis Baron, David Denison... to mention just a few. Together with the advisors appearing in the Acknowledgements (f.i. -

The Emergence of Standard English

University of Kentucky UKnowledge English Language English Language and Literature 10-19-1995 The Emergence of Standard English John H. Fisher Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Fisher, John H., "The Emergence of Standard English" (1995). English Language. 1. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_english_language_and_literature/1 THE EMERGENCE OF STANDARD ENGLISH THE EMERGENCE OF ~t STANDARD ENGLISH~- ..., h t\( ~· '1~,- ~· n~· John H. Fisher Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright© 1996 by The University Press of Kentucky The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Fuson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Fisher, John H. The emergence of standard English I John H. Fisher. p. em. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN Q-8131-1935-9 (cloth : alk. -

British Accents and Dialects

British Accents and Dialects www.bl.uk/british-accents-and-dialects Resources consulted in creating British Accents and Dialects Books Bauer, L. & Trudgill, P. 1998. Language Myths. Harmondsworth: Penguin Beal, J. 2006. Language and Region. London: Routledge Beard, A. 2004. Language Change. London: Routledge Crystal, D. 2002. The English Language: A Guided Tour of the Language, 2nd Edn. Harmondsworth: Penguin Crystal, D. 2003. English as a Global Language, 2nd Edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Crystal, D. 2004. The Stories of English. Harmondsworth: Penguin Crystal, D. 2011. Evolving English: One Language, Many Voices. London: British Library Chambers, J. & Trudgill, P. 1998. Dialectology, 2nd Edn. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press Cruttenden, A. 2001. Gimson's Pronunciation of English, 6th Edn. London: Hodder Arnold Dent, S. 2011. How to Talk Like a Local: From Cockney to Geordie. London: Random House Elmes, S. 2005. Talking for Britain. Harmondsworth: Penguin Foulkes, P., & Gerard D. (eds.) 1999. Urban Voices: Accent Studies in the British Isles. London: Arnold Hughes, A., Trudgill, P. & Watt, D. 2005. English Accents and Dialects: An Introduction to Social and Regional Varieties of English in the British Isles, 4th edn. London: Hodder Arnold Kortmann, B. & Upton, C. (eds.) 2008. Varieties of English 1: The British Isles. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter Opie, I. & P. 1987. The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren. Oxford: Oxford University Press Orton, H. 1962. Survey of English Dialects (A): An Introduction. Leeds: E J Arnold and Son Ltd. Orton, H., Halliday, W. & Barry, M. (eds.) 1962-1971. Survey of English Dialects (B): The Basic Material, Vols.1- 4. Leeds: E.J. -

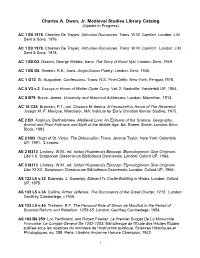

Charles A. Owen, Jr. Medieval Studies Library Catalog (Update in Progress)

Charles A. Owen, Jr. Medieval Studies Library Catalog (Update in Progress) AC 1 E8 1976 Chretien De Troyes. Arthurian Romances. Trans. W.W. Comfort. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1976. AC 1 E8 1978 Chretien De Troyes. Arthurian Romances. Trans. W.W. Comfort. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1978. AC 1 E8 D3 Dasent, George Webbe, trans. The Story of Burnt Njal. London: Dent, 1949. AC 1 E8 G6 Gordon, R.K., trans. Anglo-Saxon Poetry. London: Dent, 1936. AC 1 G72 St. Augustine. Confessions. Trans. R.S. Pine-Coffin. New York: Penguin,1978. AC 5 V3 v.2 Essays in Honor of Walter Clyde Curry. Vol. 2. Nashville: Vanderbilt UP, 1954. AC 8 B79 Bryce, James. University and Historical Addresses. London: Macmillan, 1913. AC 15 C55 Brannan, P.T., ed. Classica Et Iberica: A Festschrift in Honor of The Reverend Joseph M.-F. Marique. Worcester, MA: Institute for Early Christian Iberian Studies, 1975. AE 2 B3 Anglicus, Bartholomew. Medieval Lore: An Epitome of the Science, Geography, Animal and Plant Folk-lore and Myth of the Middle Age. Ed. Robert Steele. London: Elliot Stock, 1893. AE 2 H83 Hugh of St. Victor. The Didascalion. Trans. Jerome Taylor. New York: Columbia UP, 1991. 2 copies. AE 2 I8313 Lindsay, W.M., ed. Isidori Hispalensis Episcopi: Etymologiarum Sive Originum. Libri I-X. Scriptorum Classicorum Bibliotheca Oxoniensis. London: Oxford UP, 1966. AE 2 I8313 Lindsay, W.M., ed. Isidori Hispalensis Episcopi: Etymologiarum Sive Originum. Libri XI-XX. Scriptorum Classicorum Bibliotheca Oxoniensis. London: Oxford UP, 1966. AS 122 L5 v.32 Edwards, J. Goronwy. -

Investigating Regional Speech in Yorkshire: Evidence from the Millennium Memory Bank

Investigating Regional Speech in Yorkshire: Evidence from the Millennium Memory Bank Sarah Elizabeth Haigh A thesis submitted to the University of Sheffield for the degree of Master of Philosophy in the School of English Literature, Language and Linguistics January 2015 1 Abstract In this thesis I investigate the extent to which accent variation existed in Yorkshire at the turn of the millennium. I do this by examining the speech of a number of speakers from different locations around the region, recorded in 1998-9 as part of the Millennium Memory Bank oral history project conducted by the BBC and British Library. I also use this data to study change over time by comparing two generations of speakers from the Millennium Memory Bank, and also comparing those speakers with data from the Survey of English Dialects. I conduct the study focussing on two phonological variables: the GOAT vowel, and the PRICE vowel. I discuss the changes and variation found, both over time and with regard to place, with reference to dialect levelling as it has previously been described within the region, considering the possibility of the development of a „pan-Yorkshire‟ variety. My findings suggest that, although changes have clearly occurred in Yorkshire since the time of the SED, some variation within the region remains robust, and there may even be evidence of new diversity arising as urban varieties in Yorkshire cities continue to evolve. I also assess the potential of an oral history interview collection such as the Millennium Memory Bank for use in linguistic research, discussing the advantages and drawbacks of such data, and describing ways in which the collection as it currently stands could be made more accessible to linguists. -

Missouri Folklore Society Journal

Missouri Folklore Society Journal Special Issue: Songs and Ballads Volumes 27 - 28 2005 - 2006 Cover illustration: Anonymous 19th-century woodcut used by designer Mia Tea for the cover of a CD titled Folk Songs & Ballads by Mark T. Permission for MFS to use a modified version of the image for the cover of this journal was granted by Circle of Sound Folk and Community Music Projects. The Mia Tea version of the woodcut is available at http://www.circleofsound.co.uk; acc. 6/6/15. Missouri Folklore Society Journal Volumes 27 - 28 2005 - 2006 Special Issue Editor Lyn Wolz University of Kansas Assistant Editor Elizabeth Freise University of Kansas General Editors Dr. Jim Vandergriff (Ret.) Dr. Donna Jurich University of Arizona Review Editor Dr. Jim Vandergriff Missouri Folklore Society P. O. Box 1757 Columbia, MO 65205 This issue of the Missouri Folklore Society Journal was published by Naciketas Press, 715 E. McPherson, Kirksville, Missouri, 63501 ISSN: 0731-2946; ISBN: 978-1-936135-17-2 (1-936135-17-5) The Missouri Folklore Society Journal is indexed in: The Hathi Trust Digital Library Vols. 4-24, 26; 1982-2002, 2004 Essentially acts as an online keyword indexing tool; only allows users to search by keyword and only within one year of the journal at a time. The result is a list of page numbers where the search words appear. No abstracts or full-text incl. (Available free at http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Search/Advanced). The MLA International Bibliography Vols. 1-26, 1979-2004 Searchable by keyword, author, and journal title. The result is a list of article citations; it does not include abstracts or full-text.