Missouri Folklore Society Journal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

'Freezes' China Trade Deal

17- 23 May 2021 Weekly Journal of Press EU parliament ‘freezes’ China trade deal over sanctions Vincent Ni China affairs correspondent, Thu 20 May 2021 Tit-for-tat sanctions over Beijing’s treatment of Uyghurs puts halt on investment agreement 1 Weekly Journal of Press 17 - 23 May 2021 The European parliament has voted overw- the Chinese economy remain unclear. helmingly to “freeze” any consideration of The deal was controversial from the begin- a massive investment deal with China, fol- ning in Europe. Even before the negotiations lowing recent tit-for-tat sanctions over Bei- were concluded, China sceptics as well as hu- jing’s treatment of its Uyghur population in man rights advocates had long urged Brus- East Turkistan. sels to prioritise the issue of human rights in its dealing with Beijing. According to the resolution, the parliament, Then, in a dramatic turn of events in Mar- which must ratify the deal, “demands that ch, the European Union imposed sanctions China lift the sanctions before parliament can on four Chinese officials involved in Beijing’s deal with the Comprehensive Agreement on policy on East Turkistan. In response, China Investment (CAI)”. Some MEPs warned that swiftly imposed counter-sanctions that targe- the lifting of the sanctions would not in itself ted several high-profile members of the Euro- ensure the deal’s ratification. pean parliament, three members of national The vote on the motion was passed by a lan- parliaments, two EU committees, and a num- dslide, with 599 votes for, 30 votes against ber of China-focused European researchers. -

The Byrds' Mcguinn at Joe College by Kent Hoover Rock in That Era

OUTSIDE WEATHER Temperatures in the 70s Baseball team loses to for Joe College Weekend, The Chronicle li ttle chance of rain today. Duke University Volume 72, Number 135 Friday, April 15,1977 Durham, North Carolina Search reopened for Trinity dean By George Strong to his discipline," Turner observed. The University is again searching for a "There is a real sense in which a staff replacement for David Clayborne, the as position is a detour for someone who is sistant dean of Trinity College who re getting started." signed last summer. In late March, Wright informed John George Wright, the history graduate Fein, dean of Trinity College, of Ken student hired several months ago to be an tucky's offer. "I felt obliged — though assistant dean beginning this fall, has ac regretful — to release him from his ob cepted a faculty position at the University ligation to Duke," Fein said. of Kentucky, his alma mater. "I don't know whether I expected this or His decision leaves Trinity College once not," commented Richard Wells, associate again without a black academic dean. dean of Trinity College. 1 thought maybe Wright maintained that neither qualms it would work out But good people are about the Duke administration nor finan always in demand" cial considerations had entered his de Wells is heading up the screening com cision. mittee for applicants to the vacated posi Couldn't refuse tion. Fein and Gerald Wison, coordinator 1 knew I would eventually move into for the dean's staff, join Wells on the com "What kind of kids eat Armour hot dogs?" Harris Asbeil, Joe College chef, my academic field," he said, "and once the mittee. -

ALUMNI NEWSLETTER 42062Bk R1 1/29/07 11:37 AM Page 2

42062bk_r1 1/29/07 11:37 AM Page 1 2007 C APE C OD S EA C AMPS Monomoy - Wono A Family Camp You Are Cordially Invited By Berry Richardson Nancy Garran And Rick Francis To The 85th Anniversary Cape Cod Sea Camps –Monomoy and Wono 2007 Reunion Weekend and Grant W. Koch Fundraiser From Friday August 3rd thru Sunday August 5th ALUMNI NEWSLETTER 42062bk_r1 1/29/07 11:37 AM Page 2 2 CAPE COD SEA CAMPS 2007 ALUMNI NEWSLETTER CCSC Berry D. Richardson Berry’s letter It is an absolutely beautiful fall day as I write this letter to you. The leaves have changed, the air is crisp, and the sun is warm as it streams through my window. I watch a lot of the world go by in its ever changing seasons from my chair and I must say that I feel happy and blessed. Of course, it is hard for me to get up to camp and see all that is going on, but I do manage to get to “colors” and some other larger events. I have had the joy of watching my granddaughters grow up at camp with Kanchan now entering her AC year. Maya, cute little button that she is, is coming full season next summer as a JC I and I can’t wait. However, it just doesn’t seem possible that they have moved along through camp so quickly. They bring me much interesting news of the goings on at camp during the summer. Right after the summer, I attended the wonderful wedding of my sister Frances’ grandson Garran to Christie Cepetelli. -

FOLKLORE I N the MASS MEDIA Priscilla Denby Folklore Institute Indiana University As the Accompanying Cartoon (See Appendix ) Su

FOLKLORE IN THE MASS MEDIA Priscilla Denby Folklore Institute Indiana University As the accompanying cartoon (see Appendix ) suggests ,l the disclosure of the powerful phenomenon known as the "media" in contemporary society is analogous to the opening of Pandora's box. It would seem that the media, a relatively new societal force, has literally "sprung up, It full-grown, in some mysterious fashion to the surprise and bewilderment of many -- and the consternation of a few -- and become a dominant influence in our cul- ture. Moreover, in keeping with the mythological analogy, it may be safe to assume that the artist equates the media with the societal ills which were released st the touch of Pandora's hand. Whether the media is indeed a general evil in present-day American society is debatable; what is to be briefly discussed here, however, is its effect upon, and how it is affected by, folklore. Based upon the small sampling of data collected in this study, I would tentatively hold that the media's influence upon and use of folklore has undergone a great change. In the 1920's and 1930's when American society seemed to be in need of some kind of folk image as a means of self-definition and identification, the media graciously obliged; the result was a virtual inundation of the "fakelore" typified by the "folk hero" tradition of a Paul Bunyan or a Johnny Appleseed. Today such figures still inhabit the media. Yet as far as I can tell, contemporary media is less cmcerned with the invention and promulgation of non-traditional lore and more concerned with traditional texts used in various contexts. -

Jerry Garcia Song Book – Ver

JERRY GARCIA SONG BOOK – VER. 9 1. After Midnight 46. Chimes of Freedom 92. Freight Train 137. It Must Have Been The 2. Aiko-Aiko 47. blank page 93. Friend of the Devil Roses 3. Alabama Getaway 48. China Cat Sunflower 94. Georgia on My Mind 138. It Takes a lot to Laugh, It 4. All Along the 49. I Know You Rider 95. Get Back Takes a Train to Cry Watchtower 50. China Doll 96. Get Out of My Life 139. It's a Long, Long Way to 5. Alligator 51. Cold Rain and Snow 97. Gimme Some Lovin' the Top of the World 6. Althea 52. Comes A Time 98. Gloria 140. It's All Over Now 7. Amazing Grace 53. Corina 99. Goin' Down the Road 141. It's All Over Now Baby 8. And It Stoned Me 54. Cosmic Charlie Feelin' Bad Blue 9. Arkansas Traveler 55. Crazy Fingers 100. Golden Road 142. It's No Use 10. Around and Around 56. Crazy Love 101. Gomorrah 143. It's Too Late 11. Attics of My Life 57. Cumberland Blues 102. Gone Home 144. I've Been All Around This 12. Baba O’Riley --> 58. Dancing in the Streets 103. Good Lovin' World Tomorrow Never Knows 59. Dark Hollow 104. Good Morning Little 145. Jack-A-Roe 13. Ballad of a Thin Man 60. Dark Star Schoolgirl 146. Jack Straw 14. Beat it on Down The Line 61. Dawg’s Waltz 105. Good Time Blues 147. Jenny Jenkins 15. Believe It Or Not 62. Day Job 106. -

Alan Lomax: Selected Writings 1934-1997

ALAN LOMAX ALAN LOMAX SELECTED WRITINGS 1934–1997 Edited by Ronald D.Cohen With Introductory Essays by Gage Averill, Matthew Barton, Ronald D.Cohen, Ed Kahn, and Andrew L.Kaye ROUTLEDGE NEW YORK • LONDON Published in 2003 by Routledge 29 West 35th Street New York, NY 10001 www.routledge-ny.com Published in Great Britain by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane London EC4P 4EE www.routledge.co.uk Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group. This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” All writings and photographs by Alan Lomax are copyright © 2003 by Alan Lomax estate. The material on “Sources and Permissions” on pp. 350–51 constitutes a continuation of this copyright page. All of the writings by Alan Lomax in this book are reprinted as they originally appeared, without emendation, except for small changes to regularize spelling. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lomax, Alan, 1915–2002 [Selections] Alan Lomax : selected writings, 1934–1997 /edited by Ronald D.Cohen; with introductory essays by Gage Averill, Matthew Barton, Ronald D.Cohen, Ed Kahn, and Andrew Kaye. -

St. Patrick's Day Irish Celebration & Day of Irish Dance

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE MEDIA CONTACT: March 1, 2021 Krissy Schoenfelder 651.292.3276 | [email protected] Year two of virtual Day of Irish Dance and St. Patrick’s Day Celebration Virtual Irish fun for the whole family SAINT PAUL, Minn. (March 1, 2021)– The Irish Music and Dance Association has been offering a family friendly St. Patrick’s Day celebration at Landmark Center every year since the first concert in 1983! This year’s virtual celebrations bring back many performers who delight audiences each year at historic Landmark Center in St. Paul. In other years, Landmark Center is filled with guests enjoying Irish music, Irish dance, a bit of Irish theatre and special children’s entertainment. This year, the Irish Music and Dance Association and Landmark Center will welcome everyone virtually – on the IMDA website, the new IMDA YouTube Channel, IMDA’s Facebook Page, and on Landmark Center’s website and Facebook pages – for Day of Irish Dance, March 14, and the St. Patrick’s Day Irish Celebration, March 17. March 14 - The Sundays at Landmark event, “Day of Irish Dance,” will have two components. The first, all things Irish dance—history, costumes, music, lessons, etc—on Landmark Center’s website (www.landmarkcenter.org/irish-celebrations). The second component is the only in-person element of either day, a concert with Todd Menton from Landmark Center’s Market Street porch. The outdoor concert will still observe COVID-19 protocols (masks, social distancing), and will be live-streamed for those unable to attend in person. Visit the Landmark Center or IMDA website in the event of inclement weather for concert location info. -

February 2019

FebruaryFebruary Irish Music & 2019 2019 Dance Association Feabhra The mission of the Irish Music and Dance Association is to support and promote Irish music, dance, and other cultural traditions to insure their continuation. St. Paul’s Own Authentic St. Patrick’s Day Celebration for the Whole Family! Saturday, March 16 It will be a great day of music, dance and culture – fun for the whole family. So come on down to the St. Paul before the St. Patrick’s Day Parade for the fun at Landmark Center and come on back after the parade! What’s new for the St. Patrick’s Day Irish Celebration 2019? A sumptuous selection of traditional Irish music and dance with new and favorite bands and dance groups plus theater: . New bands - Irish Pub Rock the SERFs and lush vocals with fiddle, whistle, guitar, mandolin, and percussion from the Inland Seas! . This year’s Cross-Cultural Presentation offers a delightful blend of Irish and Swedish music in “Tullamore Aquavit Dew” with Phil Platt and Eric Platt in the Seminar Room. The Children’s Stage will start earlier this year, with songs with Ross Sutter – for two performances, a parent and kid céilí dance party with the Mooncoin Céili Dancers, songs from Charlie Heymann, interactive storytelling with Sir Gustav Doc’Tain, plus music and dance with Danielle Enblom. Theater with “Sadie the Goat” a one-woman show, written in verse, that tells the purportedly true story of an Irish-American woman in “Gangs of New York”-era Manhattan. Look for more on this presentation elsewhere in this newsletter. -

Classical Gas Recordings and Releases Releases of “Classical Gas” by Mason Williams

MasonMason WilliamsWilliams Full Biography with Awards, Discography, Books & Television Script Writing Releases of Classical Gas Updated February 2005 Page 1 Biography Mason Williams, Grammy Award-winning composer of the instrumental “Classical Gas” and Emmy Award-winning writer for “The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour,” has been a dynamic force in music and television circle since the 1960s. Born in Abilene, Texas in 1938, Williams spent his youth divided between living with his 1938 father in Oklahoma and his mother in Oregon. His interest in music began when, as a teenager, he to 1956 became a fan of pop songs on the radio and sang along with them for his own enjoyment. In high Oklahoma school, he sang in the choir and formed his first group, an a capella quartet that did the 1950’s City style pop and rock & roll music of the era. They called themselves The Imperials and The to L.A. Lamplighters. The other group members were Diana Allen, Irving Faught and Larry War- ren. After Williams was graduated from Northwest Classen High School in Oklahoma City in 1956, he and his lifelong friend, artist Edward Ruscha, drove to Los Angeles. There, Williams attended Los Angeles City College as a math major, working toward a career as an insurance actuary. But he spent almost as much time attending musical events, especially jazz clubs and concerts, as he did studying. This cultural experience led him to drop math and seek a career in music. Williams moved back to Oklahoma City in 1957 to pursue his interest in music by taking a crash course in piano for the summer. -

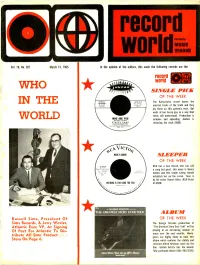

In Theopinion of Theeditors, This Week the Following Records Are The

record Formerly MUSIC worldVENDOR Vol. 19, No. 927 March 13, 1965 In theopinion of theeditors, this week the following records are the recordroll/1 world J F1,4 WHO SINGLE PICK OF THE WEEK RECORDNO. VOCAL Will. The Kama -Sutracrowdknowsthe 45-5500 iRST ACCOMP IN THE rill 12147) MAGGIE MUSS. TIME 2.06 (OW) musical tricks of the trade and they ply them on this galvanic rock.Gal wails at her bossy guy in a way that teens will understand.Production is WHO ARE YOU complexandappealing.Jubileeis WORLD (Chi Taylor-Ted Oaryll) STACEY CANE By GARY SHERMAN releasing the deck (5500). KAMA-SUTRA PRODUCTIONS pr HY MIIRAHI-PHI( STFINPERc ARTIE RIP,' NVICro#e NANCY ADAMS SLEEPER OF THE WEEK 47-8529 RCA has a new thrush who can sell Omer Productions, a song but good. Her name is Nancy Inc.,ASCAP SPHIA-1938 Adams and this single outing should 2:31 establish her on the scene. Tune is by hit writer Robert Allen. (RCA Victor NOTHING IS TOO GOOD FOR YOU 47.8529) Slew, GEORGE STEVENS THE GREATEST STORY EVER TOLD ALBUM Russell Sims, President Of OF THE WEEK Sims Records, & Jerry Wexler, TheGeorgeStevensproductionof Atlantic Exec VP, At Signing "The Greatest Story Ever Told" will be Of Pact For Atlantic To Dis- playinginan increasing number of areas over the next months.Movie- ... tribute All Sims Product. goers are highly likely to want this Story On Page 6. album which contains the stately and reverant Alfred Newman score for the film.United Artists has the beauti- fully packaged album (UAL/JAS 5120). -

To Play Jewish Again: Roots, Counterculture, and the Klezmer Revival Claire Marissa Gogan Thesis Submitted to the Faculty Of

To Play Jewish Again: Roots, Counterculture, and the Klezmer Revival Claire Marissa Gogan Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts In History David P. Cline, Co-Chair Brett L. Shadle, Co-Chair Rachel B. Gross 4 May 2016 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Identity, Klezmer, Jewish, 20th Century, Folk Revival Copyright 2016 by Claire M. Gogan To Play Jewish Again: Roots, Counterculture, and the Klezmer Revival Claire Gogan ABSTRACT Klezmer, a type of Eastern European Jewish secular music brought to the United States in the late 19th and early 20th century, originally functioned as accompaniment to Jewish wedding ritual celebrations. In the late 1970s, a group of primarily Jewish musicians sought inspiration for a renewal of this early 20th century American klezmer by mining 78 rpm records for influence, and also by seeking out living klezmer musicians as mentors. Why did a group of Jewish musicians in the 1970s through 1990s want to connect with artists and recordings from the early 20th century in order to “revive” this music? What did the music “do” for them and how did it contribute to their senses of both individual and collective identity? How did these musicians perceive the relationship between klezmer, Jewish culture, and Jewish religion? Finally, how was the genesis for the klezmer revival related to the social and cultural climate of its time? I argue that Jewish folk musicians revived klezmer music in the 1970s as a manifestation of both an existential search for authenticity, carrying over from the 1960s counterculture, and a manifestation of a 1970s trend toward ethnic cultural revival. -

Of Music. •,..,....SPECIAUSTS • RECORDED MUSIC • PAGE 10 the PENNY PITCH

BULK ,RATE U.S. POSTAGE PAID Permit N•. 24l9 K.C.,M •• and hoI loodl ,hoI fun! hoI mU9;cl PAGE 3 ,set. Warren tells us he's "letting it blow over, absorbing a lot" and trying to ma triculate. Warren also told PITCH sources that he is overwhelmed by the life of William Allan White, a journalist who never graduated from KU' and hobnobbed with Presidents. THE PENNY PITCH ENCOURAGES READERS TO CON Dear Charles, TR IBUTE--LETTERSJ ARTICLES J POETRY AND ART, . I must congratulate you on your intelli 4128 BROADWAY YOUR ENTR I ES MAY BE PR I NTED. OR I G I NALS gence and foresight in adding OUB' s Old KANSAS CITY, MISSDURI64111 WI LL NOT BE RETURNED. SEND TO: Fashioned Jazz. Corner to PENNY PITCH. (816) 561·1580 CHARLES CHANCL SR. Since I'm neither dead or in the ad busi ness (not 'too sure about the looney' bin) EDITOR .•...•. Charles Chance, Sr. PENNY PITCH BROADWAY and he is my real Ole Unkel Bob I would ASSISTING •.• Rev. Dwight Frizzell 4128 appreciate being placed on your mailing K.C. J MO 64111 ••. Jay Mandeville I ist in order to keep tabs on the old reprobate. CONTRIBUTORS: Dear Mr. Chance, Thank you, --his real niece all the way Chris Kim A, LeRoi, Joanie Harrell, Donna from New Jersey, Trussell, Ole Uncle Bob Mossman, Rosie Well, TIME sure flies, LIFE is strange, and NEWSWEEK just keeps on getting strang Beryl Sortino Scrivo, Youseff Yancey, Rev. Dwight Pluc1cemin, NJ Frizzell, Claude Santiago, Gerard and er. And speaking of getting stranger, l've Armell Bonnett, Michael Grier, Scott been closely following the rapid develop ~ Dear Beryl: .