Vices and Virtues'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Front Matter Revised

Authorial or Scribal? : spelling variation in the Hengwrt and Ellesmere manuscripts of The Canterbury Tales Caon, L.M.D. Citation Caon, L. M. D. (2009, January 14). Authorial or Scribal? : spelling variation in the Hengwrt and Ellesmere manuscripts of The Canterbury Tales. LOT, Utrecht. Retrieved from https://hdl.handle.net/1887/13402 Version: Corrected Publisher’s Version Licence agreement concerning inclusion of doctoral thesis in the License: Institutional Repository of the University of Leiden Downloaded from: https://hdl.handle.net/1887/13402 Note: To cite this publication please use the final published version (if applicable). References Baker, Donald C. (ed.) (1984), A Variorum Edition of the Works of Geoffrey Chaucer , vol. II, The Canterbury Tales, part 10, The Manciple Tale , Norman, Oklahoma: University of Oklahoma Press. Barbrook, A., Christopher J. Howe, Norman Blake, Peter Robinson (1998), ‘The Phylogeny of The Canterbury Tales ’, Nature , 394, 839. Benskin, Michael and Margaret Laing (1981), ‘Translations and Mischsprachen in Middle English Manuscripts’, in M. Benskin and M.L. Samuels (eds), So Meny People Longages and Tonges: Philological Essays in Scots and Medieval English presented to Angus McIntosh , Edinburgh: Edinburgh Middle English Dialect Project, 55–106. Benson, Larry D. (ed.) (1987), The Riverside Chaucer , 3rd edn, Boston: Houghton Mifflin. Benson, Larry D. (1992), ‘Chaucer’s Spelling Reconsidered’, English Manuscript Studies 1100 –1700 3: 1–28. Reprinted in T.M. Andersson and S.A. Barney (eds) (1995) Contradictions: From Beowulf to Chaucer , Aldershot: Scolar Press. Blake, Norman F. (ed.) (1980), The Canterbury Tales. Edited from the Henwgrt Manuscript , London: Edward Arnold. Blake, Norman F. (1985), The Textual Tradition of The Canterbury Tales , London: Edward Arnold. -

The European English Messenger

The European English Messenger Volume 21.2 – Winter 2012 Contents ESSE MATTERS 3 - Fernando Galván, The ESSE President’s Column 7 - Marina Dossena, Editorial Notes and Password 8 - Jacques Ramel, ‘Like’ the ESSE Facebook page 9 - Liliane Louvel is the new ESSE President 11 - Hortensia Pârlog is the new Editor of the European English Messenger 12 - ESSE Book Awards 2012 - ESSE Bursaries for 2013 15 - Laurence Lux-Sterritt, Doing research in the UK – on an ESSE bursary 17 - Call for applications and nominations (ESSE Secretary and Treasurer) 19 - European Journal of English Studies 20 - ESSE 12, Košice 2014 22 - Graham Caie, In memoriam : Norman Blake 24 RESEARCH - Ben Parsons, The Fall of Princes and Lydgate’s knowledge 26 of The Book of the Duchess - Jonathan P. A. Sell, The Place of English Literary Studies in the Dickens of a Crisis 31 REPORTS AND REVIEWS 36 Christoph Henke, Daniela Landert, Virginia Pulcini, Annika McPherson, Nicholas Brownlees, Dirk Schultze, Annelie Ädel, Risto Hiltunen, Iman M. Laversuch, Jessica Aliaga Lavrijsen, Judit Mudriczki, Marc C. Conner, Eoghan Smith, Onno Kosters, Elena Voj , José-Carlos Redondo-Olmedilla, Miles Leeson, Balz Engler, John Miller, Erik Martiny, Stavros Stavrou Karayanni, Mark Sullivan, Paola Di Gennaro, Benjamin Keatinge 95 ANNOUNCEMENTS FROM THE ASSOCIATIONS 96 ESSE BOARD MEMBERS: NATIONAL REPRESENTATIVES The European English Messenger, 21.2 (2012) Professor Fernando Galván’s Honorary Degree at the University of Glasgow, 13 June 2012 (in this photo, from left to right: Fernando Galván, Ann Caie, Graham Caie, Hortensia Pârlog, Lachlan Mackenzie and Slavka Tomaščiková) 2 The European English Messenger, 21.2 (2012) ______________________________________________________________________________ The ESSE President’s Column Fernando Galván _______________________________________________________________________________ Some weeks after the ESSE-11 Conference in Istanbul of 4-8 September, I still have very vivid memories of a fantastic city and a highly successful academic gathering. -

Canterbury Tales" 1

Bo/etíll Mí//ares Car/o ISSN: 0211-2140 1005-1006,14-25: 379-394 Orthography, Codicology, and Textual Studies: The Cambridge Un iversity Library, Gg.4.27 "Canterbury Tales" 1 Jacob TIIA1SEN Adam MickiewicL University SU:\lMARY An analysis 01' thc distrihution 01' orthographic variants in the Cambridge University Library, MS Gg.4.27 copy ofChauccr's CUlllahur\' Ta/es suggests that longer tranches ofthe source text were together, and partially ordered, already when it reached the scribe. The cvidencc 01' this manuscript's quiring, inks, miniatures, and ordinatio supports this finding. Studying linguistic and (other) codicological aspects 01' manuscripts may thus he 01' use to textual scholars and editors. Key words: Chaucer - Call1erhur\' Ta/cs - manuscript studies - Middle English - scribes - illu mination -- dialectology - graphemic and orthographic variation - textual studies RESUMEN El análisis de la distribución de las variantes gralcmicas en la copia de los ClIclllos dc Call1crhlllT de Chaucer en Cambridge University Lihrary, MS Gg.4.27 sugierc que fi'agmentos largos del texto ya estahan juntos y parcialmente ordenados cuando éste llego al escriba. Esta idea tamhién sc sustenta en evidencias paleográficas en el manuscrito, como las tintas, las miniaturas, los cuadernos, y la disposición en la página. El estudio de los aspectos lingüisticos y eodieológicos de los manusritos pueden serie úti les a editores y critieos textuales, Palabras clavc: Chaucer, Cllclllos dc Call1erhllr\,, manuscritos, inglés medio, escrihas, illumi nación, dialectología, variación gralcmica y ortográfica, estudios textuales INTRODUCTION The dialecto10gist Angus McIntosh has noted that one type of exemp1ar influenee has the interesting characteristic that "jt tends to assert itsc1f less and 1ess as the scribe proceeds with his work" (1975 [1989: 44 n. -

HOGG, Richard (General Ed.): the Cambridge History of the English Lan- Guage

HOGG, Richard (General Ed.): The Cambridge History of the English Lan- guage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Volume I: The Be- ginnings to 1066. Edited by Richard M. Hogg (1992). xxii + 609 pp. (£60.00). Volume II: 1066-1476. Edited by Norman Blake (1992). xxi + 703 pp. (£ 65.00). Writing a review on a major work such as this one -namely "the first multi- volume work to provide a full account of the history of English" (Presentation) is a task which remains necessarily incomplete. This is so for two obvious reasons: one, only the first two volumes are available; two, each chapter is worth reviewing in itself, for reasons that will become evident in what follows. Any overall judgement must wait then till the complete series is pub- lished; even so, these two books contain sufficient elements to predict a sucessful result for a most ambitious project. And project is really the key word: it has been carefully planned and scheduled from the very beginning as is shown by the detailed contents of all the forthcoming volumes. But as a matter of fact, this was only to be expected from the General Editor, who, besides his well known perceptiveness, expertise, and insightful knowledge, has added to the assets of this work Volume Editors and contributors such as Norman Blake, Roger Lass, John Algeo, Vivian Salmon, Cecily Clark, Malcolm Godden, Elizabeth Closs Traugott, Manfred Görlach, Matti Rissanen, Dieter Kastovsky, John Wells, James Milroy, David Burnley, Braj Kachru, Suzanne Romaine, Robert Burchfield, Dennis Baron, David Denison... to mention just a few. Together with the advisors appearing in the Acknowledgements (f.i. -

The Emergence of Standard English

University of Kentucky UKnowledge English Language English Language and Literature 10-19-1995 The Emergence of Standard English John H. Fisher Click here to let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Thanks to the University of Kentucky Libraries and the University Press of Kentucky, this book is freely available to current faculty, students, and staff at the University of Kentucky. Find other University of Kentucky Books at uknowledge.uky.edu/upk. For more information, please contact UKnowledge at [email protected]. Recommended Citation Fisher, John H., "The Emergence of Standard English" (1995). English Language. 1. https://uknowledge.uky.edu/upk_english_language_and_literature/1 THE EMERGENCE OF STANDARD ENGLISH THE EMERGENCE OF ~t STANDARD ENGLISH~- ..., h t\( ~· '1~,- ~· n~· John H. Fisher Publication of this volume was made possible in part by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities. Copyright© 1996 by The University Press of Kentucky The University Press of Kentucky Scholarly publisher for the Commonwealth, serving Bellarmine University, Berea College, Centre College of Kentucky, Eastern Kentucky University, The Fuson Historical Society, Georgetown College, Kentucky Historical Society, Kentucky State University, Morehead State University, Murray State University, Northern Kentucky University, Transylvania University, University of Kentucky, University of Louisville, and Western Kentucky University. All rights reserved. Editorial and Sales Offices: The University Press of Kentucky 663 South Limestone Street, Lexington, Kentucky 40508-4008 www.kentuckypress.com Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Fisher, John H. The emergence of standard English I John H. Fisher. p. em. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN Q-8131-1935-9 (cloth : alk. -

Lessons in Morality in a Changing World Allegories of Virtue and Vice in the Baillieu Library Print Collection Amelia Saward

Lessons in morality in a changing world Allegories of virtue and vice in the Baillieu Library Print Collection Amelia Saward As evident in texts ranging from the concurrent rediscoveries of ancient Hieronymus Wierix (c. 1553–1619).6 Bible to the writings of Aristotle philosophical teachings. Giotto’s The two representations of vice— and Thomas Aquinas, humans have figures of the virtues and vices Pride and Lust—are part of tried for millennia to understand and (situated below the cycle of frescoes Aldegrever’s series. explain the concept of morality and, on the life of the Virgin and Christ) The Raimondi prints, as well as more precisely, the human virtues and in the Scrovegni Chapel (Arena the majority of those by Beham and vices. Consequently, it is no surprise Chapel) at Padua, dating from Aldegrever, are from the significant that representations of morality 1303–05, are one of the earliest gift made by Dr J. Orde Poynton populate Western art throughout Renaissance examples.2 Along with (1906–2001) in 1959, while the history. Such representations usually an advanced understanding of time remaining prints mentioned were take the form of allegory. In the and temporality that began in the purchased by the university, bar one Renaissance’s age of humanism, medieval period, this re-emergence donated in recent years by Marion where Church principles and pagan of ancient theories heralded an era and David Adams.7 traditions were paradoxically mixed, characterised by an unsurpassed Although morality has been these representations demonstrated desire to understand the human a subject of human inquiry since the emergence and establishment of condition. -

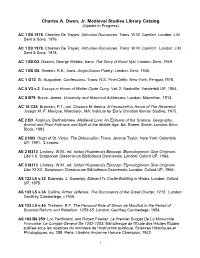

Charles A. Owen, Jr. Medieval Studies Library Catalog (Update in Progress)

Charles A. Owen, Jr. Medieval Studies Library Catalog (Update in Progress) AC 1 E8 1976 Chretien De Troyes. Arthurian Romances. Trans. W.W. Comfort. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1976. AC 1 E8 1978 Chretien De Troyes. Arthurian Romances. Trans. W.W. Comfort. London: J.M. Dent & Sons, 1978. AC 1 E8 D3 Dasent, George Webbe, trans. The Story of Burnt Njal. London: Dent, 1949. AC 1 E8 G6 Gordon, R.K., trans. Anglo-Saxon Poetry. London: Dent, 1936. AC 1 G72 St. Augustine. Confessions. Trans. R.S. Pine-Coffin. New York: Penguin,1978. AC 5 V3 v.2 Essays in Honor of Walter Clyde Curry. Vol. 2. Nashville: Vanderbilt UP, 1954. AC 8 B79 Bryce, James. University and Historical Addresses. London: Macmillan, 1913. AC 15 C55 Brannan, P.T., ed. Classica Et Iberica: A Festschrift in Honor of The Reverend Joseph M.-F. Marique. Worcester, MA: Institute for Early Christian Iberian Studies, 1975. AE 2 B3 Anglicus, Bartholomew. Medieval Lore: An Epitome of the Science, Geography, Animal and Plant Folk-lore and Myth of the Middle Age. Ed. Robert Steele. London: Elliot Stock, 1893. AE 2 H83 Hugh of St. Victor. The Didascalion. Trans. Jerome Taylor. New York: Columbia UP, 1991. 2 copies. AE 2 I8313 Lindsay, W.M., ed. Isidori Hispalensis Episcopi: Etymologiarum Sive Originum. Libri I-X. Scriptorum Classicorum Bibliotheca Oxoniensis. London: Oxford UP, 1966. AE 2 I8313 Lindsay, W.M., ed. Isidori Hispalensis Episcopi: Etymologiarum Sive Originum. Libri XI-XX. Scriptorum Classicorum Bibliotheca Oxoniensis. London: Oxford UP, 1966. AS 122 L5 v.32 Edwards, J. Goronwy. -

Missouri Folklore Society Journal

Missouri Folklore Society Journal Special Issue: Songs and Ballads Volumes 27 - 28 2005 - 2006 Cover illustration: Anonymous 19th-century woodcut used by designer Mia Tea for the cover of a CD titled Folk Songs & Ballads by Mark T. Permission for MFS to use a modified version of the image for the cover of this journal was granted by Circle of Sound Folk and Community Music Projects. The Mia Tea version of the woodcut is available at http://www.circleofsound.co.uk; acc. 6/6/15. Missouri Folklore Society Journal Volumes 27 - 28 2005 - 2006 Special Issue Editor Lyn Wolz University of Kansas Assistant Editor Elizabeth Freise University of Kansas General Editors Dr. Jim Vandergriff (Ret.) Dr. Donna Jurich University of Arizona Review Editor Dr. Jim Vandergriff Missouri Folklore Society P. O. Box 1757 Columbia, MO 65205 This issue of the Missouri Folklore Society Journal was published by Naciketas Press, 715 E. McPherson, Kirksville, Missouri, 63501 ISSN: 0731-2946; ISBN: 978-1-936135-17-2 (1-936135-17-5) The Missouri Folklore Society Journal is indexed in: The Hathi Trust Digital Library Vols. 4-24, 26; 1982-2002, 2004 Essentially acts as an online keyword indexing tool; only allows users to search by keyword and only within one year of the journal at a time. The result is a list of page numbers where the search words appear. No abstracts or full-text incl. (Available free at http://catalog.hathitrust.org/Search/Advanced). The MLA International Bibliography Vols. 1-26, 1979-2004 Searchable by keyword, author, and journal title. The result is a list of article citations; it does not include abstracts or full-text. -

Complements to Virtue

DOMINICAN A Vol. XIX SEPTEMBER, 1934 No.3 COMPLEMENTS TO VIRTUE BERNARD SHERIDAN, O.P. "Whosoever are led by the Spirit of God, they are the sons of God." Rom. viii, 14. HEN we were children we ~~tended . Catechism class daily, or at least Sunday school. I here, 111 order to reply to the [I teacher's questions, we were expected to have a reason for the faith which was in us. Among the many mystifying questions which come our way in the course of the year, there were the virtues, the gifts and fruits of the Holy Ghost and the beatitudes. Somehow we managed to grasp the notion of virtue. For us the vir tues were special blessings from God which helped us to be good. But for the rest-these gifts and fruits and beatitudes-well, with the definitions ready upon demand and with the ability to recite "trip pingly upon the tongue" the number and names of each, we were content to rest. With no more than such a catalogue, we go through life with many of the faithful, satisfied with the ability to enu merate, but unable to understand, our grand supernatural equipment. We believe, therefore, that it will be well worth while to consider briefly-though not so briefly that clarity will be sacrificed-the gifts of the Holy Ghost. I The Christian life is first and foremost a supernatural life. Why do we say that? Because the end for which God has destined us is a supernatural one. Towards this end we must strive every moment of our earthly existence. -

Holy Conversations 2

SIN SIN Focus he Greek understanding of sin (hamartia) was missing the mark. This idea is more complicated than it seems at first glance. A sinner must have knowledge of moral righteousness, a target if you will, and have knowledge of its bull’s-eye. Over the history of Christianity that target, along with its bull’s- T eye, has often been referred to as God’s law. • Our Jewish siblings conceived of sin as largely communal, with one member able to pollute the whole group. • Christians emphasized personal sin, our salvation was in our own hands. • Since early Christianity, the concept of “sin” has developed into many targets, all hanging on a backdrop of “original sin.” • Are we to understand sin as vice; as brokenness from God, ourselves, or others; as willful disobedience of God; is it dependent on our intentions, weakness to temptation, or just inevitable in life? • Is our ultimate relationship to God dependent upon God’s grace or embedded in our deeds? • Contemporary Christian theologians have articulated modern sins: racism, social injustice, debt, even un-medicated depression. • Marriage equality has been denounced as sin. The theological stigma of the LGBTQ community is so often that of “sinner.” How do we choose to reclaim our belovedness and grace in the face of this? • How do we still understand our moral shortcomings in Christian terms? Some Centering Quotes about Sin Wherever there are humans, there will be sin. (John Portman) History will absolve me. (Fidel Castro) To define sin as an act that is a violation of the law of God leaves room for differentiating sin from crimes, the latter being acts that violate human laws. -

Seven Deadly Sins Sin 5: Seven Deadly Sins

Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen Sin 5: Seven Deadly Sins Sin 5: Seven Deadly Sins Sin 5: Seven Deadly Sins good) the sufficiency and contentment that can be found only in God (an eternal, infinite good), and The seven deadly sins — known for most of their they depend on themselves to provide that good early history as the seven capital vices — constituted rather than trusting God to do so. The intensely de- an important schema of sins that was used by Chris- sirable ends of the seven vices spawn other sins that tians for self-examination, ® confession, ® preach- serve those ends or are the effects of one’s excessive ing, and spiritual formation for nearly a millen- pursuit of them. For example, the offspring of ava- nium. Popular treatments of the seven use “sin” and rice typically includes “fraud” and “insensibility to “vice” as synonymous terms. Technically, however, mercy.” “vice” is a more specific term than “sin,” since it re- The list of vices in its most typical form includes fers only to a character trait, rather than applying to pride. Alternately, on the basis of Sir. 10:15 (“Pride a general human condition (“original sin,” “sinful is the beginning of all sin,” DV), Gregory named nature”), a specific action (“sins of thought, word, seven other vices, including vainglory, offshoots of or deed”), or social structures (“institutional rac- pride. However, pride occasionally competed for ism, a structural sin”). status as the queen of the other vices with avarice, The seven vices can be traced back as far as given the apostle Paul’s statement that love of Evagrius Ponticus (346-99), in his practical guides money is the root of all evil (1 Tim. -

PH 'The Four Cardinal Virtues'

Notes from a Preceptor’s Handbook A Preceptor: (OED) 1440 A.D. from Latin praeceptor one who instructs, a teacher, a tutor, a mentor Provincial Grand Lodge of Wiltshire Provincial W Bro Michael Lee CBE, PJGD Past Preceptor Stonehenge Lodge No.6114 August 2019 The Four Cardinal Virtues The quite splendid 'Charge after Initiation' offers a new Mason the first hint of the human qualities his brethren prize most highly... 'let Prudence direct you, Temperance chasten you, Fortitude support you and Justice be the guide of all your actions...and maintain those truly Masonic ornaments – Benevolence and Charity'. Those fortunate enough these days to listen regularly to a well-delivered 'First Degree Tracing Board' will recall as the ritualist draws towards its end he leaves with us the thought that: 'Pendant to the corners of the lodge are four tassels, meant to remind us of the four cardinal virtues Temperance, Fortitude, Precedence and Justice... He then adds: 'the characteristics of a good mason are Virtue, Honour and Mercy. May they ever be found in a Freemason's breast.' As Speculative Freemasonry is, first and foremost, a system of morality it perhaps should come as no surprise that virtue, a particular quality of moral excellence, should be prized so highly. It perhaps begs the question though of why just four virtues are considered pre-eminent or 'cardinal' and, from the galaxy of admirable traits available for selection, why those four particular qualities have been chosen. This short paper attempts to address these two questions. History The search for the elements of moral excellence has had a long history, commencing well before our Leaders compiled their joint ritual over 1813-17.