HNA April 11 Cover-Final.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Un Univers Intime Paintings in the Frits Lugt Collection 1St March - 27 Th May 2012

Institut Centre culturel 121 rue de Lille - 75007 Paris Néerlandais des Pays-Bas www.institutneerlandais.com UN UNIVERS INTIME PAINTINGS IN THE FRITS LUGT COLLECTION 1ST MARCH - 27 TH MAY 2012 MAI 2012 Pieter Jansz. Saenredam (Assendelft 1597 - 1665 Haarlem) Choir of the Church of St Bavo in Haarlem, Seen from the Christmas Chapel , 1636 UN UNIVERS Paintings in the Frits INTIME Lugt Collection Press Release The paintings of the Frits Lugt Collection - topographical view of a village in the Netherlands. Fondation Custodia leave their home for the The same goes for the landscape with trees by Jan Institut Néerlandais, displaying for the first time Lievens, a companion of Rembrandt in his early the full scope of the collection! years, of whom very few painted landscapes are known. The exhibition Un Univers intime offers a rare Again, the peaceful expanse of water in the View of a opportunity to view this outstanding collection of Canal with Sailing Boats and a Windmill is an exception pictures (Berchem, Saenredam, Maes, Teniers, in the career of Ludolf Backhuysen, painter of Guardi, Largillière, Isabey, Bonington...), expanded tempestuous seascapes. in the past two years with another hundred works. The intimate interiors of Hôtel Turgot, home to the Frits Lugt Collection, do indeed keep many treasures which remain a secret to the public. The exhibition presents this collection which was created gradually, with great passion and discernment, over nearly a century, in a selection of 115 paintings, including masterpieces of the Dutch Golden Age, together with Flemish, Italian, French and Danish paintings. DUTCH OF NOTE Fig. -

A Cidade Real E Ideal: a Paisagem De Nuremberg Na Crônica De Hartmann Schedel E a Sua Concepção De Espaço Urbano

A CIDADE REAL E IDEAL: A PAISAGEM DE NUREMBERG NA CRÔNICA DE HARTMANN SCHEDEL E A SUA CONCEPÇÃO DE ESPAÇO URBANO LA CIUDAD REAL E IDEAL: EL PAISAJE DE NUREMBERG EN LA CRÓNICA DE HARTMANN SCHEDEL Y SU CONCEPCIÓN DE ESPACIO URBANO THE REAL AND IDEAL CITY: THE NUREMBERG LANDSCAPE IN HARTMANN SCHEDEL’S CHRONICLE AND ITS CONCEPTION OF URBAN SPACE Vinícius de Freitas Morais Universidade Federal Fluminense [email protected] Fecha de recepción: 11/10/2016 Fecha de aprobación: 01/06/2017 Resumo A partir de uma concepção de espaço confeccionada pela elite local de Nuremberg, buscava-se, através de um projeto tipográfico promover uma imagem ideal para esta cidade. Hartmann Schedel, um importante humanista local em conjunto com o impressor Anton Koberger e os gravadores Micheal Wolgemut e Wilhem Pleydenwurff produziram duas edições do imponente incunábulo comumente conhecido pela historiografia como A Crônica de Nuremberg. Este presente artigo tenta, a partir de uma comparação entre fonte escrita e imagética, elucidar esta apologia de Nuremberg como um importante polo econômico para a região da Baviera. Palavras-chave Cidade – Incunábulo - humanismo Resumen A partir de una concepción de espacio confeccionada por la élite local de Nuremberg, se buscaba, a través de un proyecto tipográfico promover una imagen ideal para esta ciudad. Hartmann Schedel, un importante humanista local, en conjunto con el impresor Anton Koberger y los grabadores Micheal Wolgemut y Wilhem Pleydenwurff, produjeron dos ediciones del imponente incunable comúnmente conocido por la historiografía como La Crónica de Nuremberg. Este presente artículo intenta, a partir de una comparación entre fuente escrita e imagética, elucidar esta apología de Nuremberg como un importante polo económico para la región de Baviera. -

Julius S. Held Papers, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt3g50355c No online items Finding aid for the Julius S. Held papers, ca. 1921-1999 Isabella Zuralski. Finding aid for the Julius S. Held 990056 1 papers, ca. 1921-1999 Descriptive Summary Title: Julius S. Held papers Date (inclusive): ca. 1918-1999 Number: 990056 Creator/Collector: Held, Julius S (Julius Samuel) Physical Description: 168 box(es)(ca. 70 lin. ft.) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: Research papers of Julius Samuel Held, American art historian renowned for his scholarship in 16th- and 17th-century Dutch and Flemish art, expert on Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. The ca. 70 linear feet of material, dating from the mid-1920s to 1999, includes correspondence, research material for Held's writings and his teaching and lecturing activities, with extensive travel notes. Well documented is Held's advisory role in building the collection of the Museo de Arte de Ponce in Puerto Rico. A significant portion of the ca. 29 linear feet of study photographs documents Flemish and Dutch artists from the 15th to the 17th century. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in English Biographical / Historical Note The art historian Julius Samuel Held is considered one of the foremost authorities on the works of Peter Paul Rubens, Anthony van Dyck, and Rembrandt. -

November 2012 Newsletter

historians of netherlandish art NEWSLETTER AND REVIEW OF BOOKS Dedicated to the Study of Netherlandish, German and Franco-Flemish Art and Architecture, 1350-1750 Vol. 29, No. 2 November 2012 Jan and/or Hubert van Eyck, The Three Marys at the Tomb, c. 1425-1435. Oil on panel. Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam. In the exhibition “De weg naar Van Eyck,” Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, October 13, 2012 – February 10, 2013. HNA Newsletter, Vol. 23, No. 2, November 2006 1 historians of netherlandish art 23 S. Adelaide Avenue, Highland Park, NJ 08904 Telephone: (732) 937-8394 E-Mail: [email protected] www.hnanews.org Historians of Netherlandish Art Offi cers President - Stephanie Dickey (2009–2013) Bader Chair in Northern Baroque Art Queen’s University Kingston ON K7L 3N6 Canada Vice-President - Amy Golahny (2009–2013) Lycoming College Williamsport, PA 17701 Treasurer - Rebecca Brienen University of Miami Art & Art History Department PO Box 248106 Coral Gables FL 33124-2618 European Treasurer and Liaison - Fiona Healy Seminarstrasse 7 D-55127 Mainz Germany Contents Board Members President's Message .............................................................. 1 Paul Crenshaw (2012-2016) HNA News ............................................................................1 Wayne Franits (2009-2013) Personalia ............................................................................... 2 Martha Hollander (2012-2016) Exhibitions ............................................................................ 3 Henry Luttikhuizen (2009 and 2010-2014) -

The Drawings of Cornelis Visscher (1628/9-1658) John Charleton

The Drawings of Cornelis Visscher (1628/9-1658) John Charleton Hawley III Jamaica Plain, MA M.A., History of Art, Institute of Fine Arts – New York University, 2010 B.A., Art History and History, College of William and Mary, 2008 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Art and Architectural History University of Virginia May, 2015 _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ _______________________________________ Table of Contents Abstract ............................................................................................................................................. i Acknowledgements.......................................................................................................................... ii Introduction ..................................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter 1: The Life of Cornelis Visscher .......................................................................................... 3 Early Life and Family .................................................................................................................... 4 Artistic Training and Guild Membership ...................................................................................... 9 Move to Amsterdam ................................................................................................................. -

Research on Tallinn's Dance of Death and Mai Lumiste – Questions and Possibilities in the 20Th Century*

KRISTA ANDRESON 96 1. Dance of Death in St Nicholas’ Church in Tallinn. Art Museum of Estonia, Niguliste Museum. Photo by Stanislav Stepaško. Tallinna Niguliste kiriku „Surmatants”. Eesti Kunstimuuseum, Niguliste muuseum. Foto Stanislav Stepaško. Research on Tallinn’s Dance of Death and Mai Lumiste – Questions and Possibilities in the 20th Century* Krista ANDRESON The aim of this article is to focus on the role of Mai Lumiste in the history of researching Tallinn’s Dance of Death, her points of departure, and those of her predecessors, and their methodological bases. When speaking of Lumiste’s contribution, the emphasis has always been on the fact that her positions were based on the technical studies conducted in Moscow between 1962 and 1965, which made the style assessment and iconographic analysis of the work possible for the first time. The literature also reflects the opinion that this research in Moscow confirmed the position that had been accepted until that time, i.e. that the author of the work was Bernt Notke. The following survey focuses on which positions formulated at that time were established on the basis of technical research and which issues still remain unresolved. Tallinn’s Dance of Death (Danse macabre) is undoubtedly the most famous medieval work of art in Estonia. It is a fragment painted on canvas. It is 7.5 metres high and 1.63 metres wide, and depicts 13 figures: the narrator of the story (a preacher) * The article was completed with the help of PUT 107 grant. The author thanks Juta Keevallik for her comprehensive critique of the article. -

Open Access Version Via Utrecht University Repository

Philosopher on the throne Stanisław August’s predilection for Netherlandish art in the context of his self-fashioning as an Enlightened monarch Magdalena Grądzka Philosopher on the throne Magdalena Grądzka Philosopher on the throne Stanisław August’s predilection for Netherlandish art in the context of his self-fashioning as an Enlightened monarch Magdalena Grądzka 3930424 March 2018 Master Thesis Art History of the Low Countries in its European Context University of Utrecht Prof. dr. M.A. Weststeijn Prof. dr. E. Manikowska 1 Philosopher on the throne Magdalena Grądzka Index Introduction p. 4 Historiography and research motivation p. 4 Theoretical framework p. 12 Research question p. 15 Chapters summary and methodology p. 15 1. The collection of Stanisław August 1.1. Introduction p. 18 1.1.1. Catalogues p. 19 1.1.2. Residences p. 22 1.2. Netherlandish painting in the collection in general p. 26 1.2.1. General remarks p. 26 1.2.2. Genres p. 28 1.2.3. Netherlandish painting in the collection per stylistic schools p. 30 1.2.3.1. The circle of Rubens and Van Dyck p. 30 1.2.3.2. The circle of Rembrandt p. 33 1.2.3.3. Italianate landscapists p. 41 1.2.3.4. Fijnschilders p. 44 1.2.3.5. Other Netherlandish artists p. 47 1.3. Other painting schools in the collection p. 52 1.3.1. Paintings by court painters in Warsaw p. 52 1.3.2. Italian paintings p. 53 1.3.3. French paintings p. 54 1.3.4. German paintings p. -

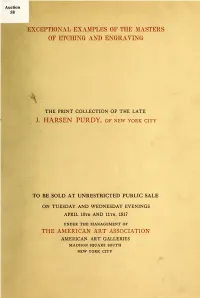

Exceptional Examples of the Masters of Etching and Engraving : the Print Collection of the Late J. Harsen Purdy, of New York

EXCEPTIONAL EXAMPLES OF THE MASTERS OF ETCHINa AND ENGRAVING THE PRINT COLLECTION OF THE LATE J. HARSEN PURDY, of new york city TO BE SOLD AT UNRESTRICTED PUBLIC SALE ON TUESDAY AND WEDNESDAY EVENINGS APRIL 10th and 11th, 1917 UNDER THE MANAGEMENT OF THE AMERICAN ART ASSOCIATION AMERICAN ART GALLERIES MADISON SQUARE SOUTH NEW YORK CITY smithsoniaM INSTITUTION 3i< 7' THE AMERICAN ART ASSOCIATION DESIGNS ITS CATALOGUES AND DIRECTS ALL DETAILS OF ILLUSTRATION TEXT AND TYPOGRAPHY ON PUBLIC EXHIBITION AT THE AMERICAN ART GALLERIES MADISON SQUARE SOUTH, NEW YORK ENTRANCE, 6 EAST 23rd STREET BEGINNING THURSDAY, APRIL 5th, 1917 MASTERPIECES OF ENGRAVERS AND ETCHERS THE PRINT COLLECTION OF THE LATE J. HARSEN PURDY, of new york city TO BE SOLD AT UNRESTRICTED PUBLIC SALE BY ORDER OF ALBERT W. PROSS, ESQ., AND THE NEW YORK TRUST COMPANY, AS EXECUTORS ON TUESDAY AND WEDNESDAY EVENINGS APRIL 10th and 11th, 1917 AT 8:00 O'CLOCK IN THE EVENINGS AT THE AMERICAN ART GALLERIES ALBRECHT DURER, ENGRAVING Knight, Death and the Devil [No. 69] EXCEPTIONAL EXAMPLES OF THE MASTERS OF ETCHING AND ENGRAVING THE PRINT COLLECTION OF THE LATE J. HARSEN PURDY, of new york city TO BE sold at unrestricted PUBLIC SALE BY ORDER OF ALBERT W. PROSS, ESQ., AND THE NEW YORK TRUST COMPANY, AS EXECUTORS ON TUESDAY AND WEDNESDAY, APRIL 10th AND 11th AT 8:00 O'CLOCK IN THE EVENINGS THE SALE TO BE CONDUCTED BY MR. THOMAS E. KIRBY AND HIS ASSISTANTS, OF THE AMERICAN ART ASSOCIATION, Managers NEW YORK CITY 1917 ——— ^37 INTRODUCTORY NOTICE REGARDING THE PRINT- COLLECTION OF THE LATE MR. -

A Companion to Reformed Orthodoxy Brill’S Companions to the Christian Tradition

A Companion to Reformed Orthodoxy Brill’s Companions to the Christian Tradition A series of handbooks and reference works on the intellectual and religious life of Europe, 500–1800 Editor-in-Chief Christopher M. Bellitto (Kean University) VOLUME 40 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/bcct A Companion to Reformed Orthodoxy Edited by Herman J. Selderhuis LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 Cover illustration: Franeker University Library. Courtesy: Tresoar, Leeuwarden, Atlas Schoemaker. This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 1871-6377 ISBN 978-90-04-23622-6 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-24891-5 (e-book) Copyright 2013 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers and Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. This book is printed on acid-free paper. CONTENTS List of Contributors ........................................................................................ vii Abbreviations ................................................................................................... ix Introduction ..................................................................................................... 1 Herman J. Selderhuis PART I RELATIONS Reformed Orthodoxy: A Short History of Research ............................ -

Short Notice the Empress and the Black Art: an Early Mezzotint by Eleonora Gonzaga (1630-1686)*

the rijks the empress and the black art: an early mezzotintmuseum by eleonora gonzaga (1630-1686) bulletin Short notice The Empress and The Black Art: An Early Mezzotint by Eleonora Gonzaga (1630-1686)* • joyce zelen • he Print Room of the Rijks- < Fig. 1 Empress Eleonora and the Arts T museum in Amsterdam has in eleonora Eleonora Maddalena Gonzaga, daughter its collection a small mezzotint of a gonzaga, of Carlo ii Gonzaga, Duke of Mayenne, soldier wearing a decorative helmet Bust of a Roman and his wife Maria Gonzaga, was born Soldier, 1660. (fig. 1). The subject of this print is far on 18 November 1630, bearing the Mezzotint, from unique and the quality of the 144 x 113 mm. title Princess of Mantua, Nevers and 2 execution is by no means exceptional. Amsterdam, Rethel. As a young princess, Eleonora Nonetheless, this particular little print Rijksmuseum, inv. no. received an excellent education. She was is worthy of mention – solely because rp-p-1892-a-16745. fluent in several languages and well- of the signature and date in the upper versed in literature, music and art. left corner: Leonora Imperatrix fecit She was also a good dancer and a Ao. 1660. The year tells us that we are poet, and she enjoyed embroidery. dealing with an extremely early mezzo - On 30 April 1651 she married the tint. The technique was invented in Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand iii the sixteen-forties and did not become (1608-1657), who was twenty years popular on a much wider scale until her senior, and took up residence in some decades later. -

Introduction

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Clashes of discourses: Humanists and Calvinists in seventeenth-century academic Leiden Kromhout, D. Publication date 2016 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Kromhout, D. (2016). Clashes of discourses: Humanists and Calvinists in seventeenth- century academic Leiden. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:26 Sep 2021 Introduction Ill. 1: Pageant at the inauguration of Leiden University, Anonymous (1575) The inauguration of Leiden University on 8 February 1575 was a moment of great importance in the process of growing self-awareness in the Northern Netherlands. After a troublesome start, the Revolt was finally gaining momentum. It has often been debated whether the Dutch Revolt was a matter of money, government, or religion.2 The fact is that both nobility and the ruling class and a substantial proportion of the common people were not content with Philip II’s measures pertaining to all these areas. -

From Stockholm to Tallinn the North Between East and West Stockholm, Turku, Helsinki, Tallinn, 28/6-6/7/18

CHAIN Cultural Heritage Activities and Institutes Network From Stockholm to Tallinn the north between east and west Stockholm, Turku, Helsinki, Tallinn, 28/6-6/7/18 Henn Roode, Seascape (Pastose II, 1965 – KUMU, Tallinn) The course is part of the EU Erasmus+ teacher staff mobility programme and organised by the CHAIN foundation, Netherlands Contents Participants & Programme............................................................................................................2 Participants............................................................................................................................3 Programme............................................................................................................................4 Performance Kalevala..............................................................................................................6 Stockholm................................................................................................................................10 Birka...................................................................................................................................11 Stockholm...........................................................................................................................13 The Allah ring.......................................................................................................................14 The Vasa.............................................................................................................................15