Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Intersection of Art and Ritual in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Visual Culture

Picturing Processions: The Intersection of Art and Ritual in Seventeenth-century Dutch Visual Culture By © 2017 Megan C. Blocksom Submitted to the graduate degree program in Art History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Chair: Dr. Linda Stone-Ferrier Dr. Marni Kessler Dr. Anne D. Hedeman Dr. Stephen Goddard Dr. Diane Fourny Date Defended: November 17, 2017 ii The dissertation committee for Megan C. Blocksom certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Picturing Processions: The Intersection of Art and Ritual in Seventeenth-century Dutch Visual Culture Chair: Dr. Linda Stone-Ferrier Date Approved: November 17, 2017 iii Abstract This study examines representations of religious and secular processions produced in the seventeenth-century Northern Netherlands. Scholars have long regarded representations of early modern processions as valuable sources of knowledge about the rich traditions of European festival culture and urban ceremony. While the literature on this topic is immense, images of processions produced in the seventeenth-century Northern Netherlands have received comparatively limited scholarly analysis. One of the reasons for this gap in the literature has to do with the prevailing perception that Dutch processions, particularly those of a religious nature, ceased to be meaningful following the adoption of Calvinism and the rise of secular authorities. This dissertation seeks to revise this misconception through a series of case studies that collectively represent the diverse and varied roles performed by processional images and the broad range of contexts in which they appeared. Chapter 1 examines Adriaen van Nieulandt’s large-scale painting of a leper procession, which initially had limited viewership in a board room of the Amsterdam Leprozenhuis, but ultimately reached a wide audience through the international dissemination of reproductions in multiple histories of the city. -

HNA April 11 Cover-Final.Indd

historians of netherlandish art NEWSLETTER AND REVIEW OF BOOKS Dedicated to the Study of Netherlandish, German and Franco-Flemish Art and Architecture, 1350-1750 Vol. 28, No. 1 April 2011 Jacob Cats (1741-1799), Summer Landscape, pen and brown ink and wash, 270-359 mm. Hamburger Kunsthalle. Photo: Christoph Irrgang Exhibited in “Bruegel, Rembrandt & Co. Niederländische Zeichnungen 1450-1850”, June 17 – September 11, 2011, on the occasion of the publication of Annemarie Stefes, Niederländische Zeichnungen 1450-1850, Kupferstichkabinett der Hamburger Kunsthalle (see under New Titles) HNA Newsletter, Vol. 23, No. 2, November 2006 1 historians of netherlandish art 23 S. Adelaide Avenue, Highland Park, NJ 08904 Telephone/Fax: (732) 937-8394 E-Mail: [email protected] www.hnanews.org Historians of Netherlandish Art Offi cers President - Stephanie Dickey (2009–2013) Bader Chair in Northern Baroque Art Queen’s University Kingston ON K7L 3N6 Canada Vice-President - Amy Golahny (2009–2013) Lycoming College Williamsport, PA 17701 Treasurer - Rebecca Brienen University of Miami Art & Art History Department PO Box 248106 Coral Gables FL 33124-2618 European Treasurer and Liaison - Fiona Healy Seminarstrasse 7 D-55127 Mainz Germany Board Members Contents Dagmar Eichberger (2008–2012) HNA News ............................................................................1 Wayne Franits (2009–2013) Matt Kavaler (2008–2012) Personalia ............................................................................... 2 Henry Luttikhuizen (2009 and 2010–2014) Exhibitions -

Neo-Latin News

44 SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY NEWS NEO-LATIN NEWS Vol. 61, Nos. 1 & 2. Jointly with SCN. NLN is the official publica- tion of the American Association for Neo-Latin Studies. Edited by Craig Kallendorf, Texas A&M University; Western European Editor: Gilbert Tournoy, Leuven; Eastern European Editors: Jerzy Axer, Barbara Milewska-Wazbinska, and Katarzyna To- maszuk, Centre for Studies in the Classical Tradition in Poland and East-Central Europe, University of Warsaw. Founding Editors: James R. Naiden, Southern Oregon University, and J. Max Patrick, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and Graduate School, New York University. ♦ Petrarch and St. Augustine: Classical Scholarship, Christian Theol- ogy and the Origins of the Renaissance in Italy. By Alexander Lee. Brill’s Studies in Intellectual History, 210. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2012. x + 382 pp. $177. Petrarch’s opera is extensive, that of Augustine is extraordinarily vast, and the literature on both is vaster still. To bridge them successfully is a significant undertaking. Over the past fifty years, scholars have attempted this task, from classic studies by Charles Trinkaus (often discussed here) to more recent ones such as C. Quillen’s Rereading the Renaissance: Petrarch, Augustine and the Language of Humanism (1995) and M. Gill’s Augustine in the Italian Renaissance: Art and Philosophy from Petrarch to Michelangelo (2005). In a new study, Alexander Lee argues that “Petrarch’s thought on moral questions was derived principally from the writings of St. Augustine” (24). Lee contends that Petrarch, rather than being philosophically inconsistent as is often suggested, was especially influenced by Augustine’s early works, most notably the Soliloquies and the De vera religione, which provided him with an interpretive method for incorporating classical literature and philosophy into Christian moral theology. -

A Companion to Reformed Orthodoxy Brill’S Companions to the Christian Tradition

A Companion to Reformed Orthodoxy Brill’s Companions to the Christian Tradition A series of handbooks and reference works on the intellectual and religious life of Europe, 500–1800 Editor-in-Chief Christopher M. Bellitto (Kean University) VOLUME 40 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/bcct A Companion to Reformed Orthodoxy Edited by Herman J. Selderhuis LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 Cover illustration: Franeker University Library. Courtesy: Tresoar, Leeuwarden, Atlas Schoemaker. This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 1871-6377 ISBN 978-90-04-23622-6 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-24891-5 (e-book) Copyright 2013 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Global Oriental, Hotei Publishing, IDC Publishers and Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior written permission from the publisher. Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use is granted by Koninklijke Brill NV provided that the appropriate fees are paid directly to The Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Suite 910, Danvers, MA 01923, USA. Fees are subject to change. This book is printed on acid-free paper. CONTENTS List of Contributors ........................................................................................ vii Abbreviations ................................................................................................... ix Introduction ..................................................................................................... 1 Herman J. Selderhuis PART I RELATIONS Reformed Orthodoxy: A Short History of Research ............................ -

The Humanist Discourse in the Northern Netherlands

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Clashes of discourses: Humanists and Calvinists in seventeenth-century academic Leiden Kromhout, D. Publication date 2016 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Kromhout, D. (2016). Clashes of discourses: Humanists and Calvinists in seventeenth- century academic Leiden. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:26 Sep 2021 Chapter 1: The humanist discourse in the Northern Netherlands This chapter will characterize the discourse of the Leiden humanists in the first decade of the seventeenth century. This discourse was in many aspects identical to the discourse of the Republic of Letters. The first section will show how this humanist discourse found its place at Leiden University through the hands of Janus Dousa and others. -

The Roots of Nationalism

HERITAGE AND MEMORY STUDIES 1 HERITAGE AND MEMORY STUDIES Did nations and nation states exist in the early modern period? In the Jensen (ed.) field of nationalism studies, this question has created a rift between the so-called ‘modernists’, who regard the nation as a quintessentially modern political phenomenon, and the ‘traditionalists’, who believe that nations already began to take shape before the advent of modernity. While the modernist paradigm has been dominant, it has been challenged in recent years by a growing number of case studies that situate the origins of nationalism and nationhood in earlier times. Furthermore, scholars from various disciplines, including anthropology, political history and literary studies, have tried to move beyond this historiographical dichotomy by introducing new approaches. The Roots of Nationalism: National Identity Formation in Early Modern Europe, 1600-1815 challenges current international scholarly views on the formation of national identities, by offering a wide range of contributions which deal with early modern national identity formation from various European perspectives – especially in its cultural manifestations. The Roots of Nationalism Lotte Jensen is Associate Professor of Dutch Literary History at Radboud University, Nijmegen. She has published widely on Dutch historical literature, cultural history and national identity. Edited by Lotte Jensen The Roots of Nationalism National Identity Formation in Early Modern Europe, 1600-1815 ISBN: 978-94-6298-107-2 AUP.nl 9 7 8 9 4 6 2 9 8 1 0 7 2 The Roots of Nationalism Heritage and Memory Studies This ground-breaking series examines the dynamics of heritage and memory from a transnational, interdisciplinary and integrated approaches. -

Quaestiones Infinitiae

Quaestiones Infinitiae PUBLICATIONS OF THE DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY AND RELIGIOUS STUDIES UTRECHT UNIVERSITY VOLUME LXXII Copyright © 2013 by R.O. Buning All rights reserved Cover illustrations, above: Reneri’s signature from his letter to De Wilhem of 22 October 1631 (courtesy of Universiteitsbibliotheek Leiden). Below: Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn, Portrait of a Scholar (1631), The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia/Wikimedia Commons, http://commons.wikimedia.org /wiki/File:Rembrandt_Harmenszoon_van_Rijn_-_A_Scholar.JPG. Cover design: R.O. Buning This publication has been typeset in the “Brill” typeface. © 2011 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. All rights reserved. http://www.brill.com/brill-typeface Printed by Wöhrmann Printing Service, Zutphen ISBN 978-94-6103-036-8 Henricus Reneri (1593-1639) Descartes’ Quartermaster in Aristotelian Territory Henricus Reneri (1593-1639) Descartes’ kwartiermaker in aristotelisch territorium (met een samenvatting in het Nederlands) Proefschrift ter verkrijging van de graad van doctor aan de Universiteit Utrecht op gezag van de rector magnificus, prof. dr. G.J. van der Zwaan, ingevolge het besluit van het college voor promoties in het openbaar te verdedigen op dinsdag 12 november 2013 des middags te 12.45 uur door Robin Onno Buning geboren op 7 juni 1977 te Nijmegen Promotor: Prof. dr. Th.H.M. Verbeek The research for this dissertation has been conducted within the project “Descartes and his Network,” which was made possible by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research (NWO) under grant number 360-20-140. Contents Acknowledgements ix Abbreviations xi Introduction 1 Chapter 1. Biography I: A Promising Philosopher 13 1.1. Birth and Early Youth (1593-1611) 13 1.2. -

Illinois Classical Studies

27 Platons KuB und seine Folgen WALTHER LUDWIG "... when instantly Phoebe grew more composed, after two or three sighs, and heart-fetched Oh's! and giving me a kiss that seemed to exhale her soul through her lips, she replaced the bed-cloaths over us." John Cleland (1709-1789) laBt in seinen "Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure" (zucrst gedruckt London 1749) Fanny Hill diese Erinnerungen aussprechen.' Nur wenigen Lesem des popularen Romans wird aufgefallen sein, daB die Vorstellung der Seele, die wahrend eines Kusses durch die Lippen zum Partner uberzugehen scheint, natiirlich direkt oder indirekt auf ein beriihmtes, bis ins 20. Jahrhundert Platon zugeschriebcnes Epigramm zuruckgeht, vielleicht direkt, da John Clclands Bildung durchaus ausreichte, um dieses Epigramm in seiner griechischen Originalform oder in eincr seiner lateinischen Obersetzungen zu kennen (er hatte ab 1722 die humanistisch orientierte Westminster School in London besucht und schrieb 1755 das Drama "Titus Vespasian" uber den romischen Kaiser), und sicher indirekt, da das Motiv langst in die neulateinische und nationalsprachliche Liebesdichtung eingegangen war. Grundsatzlich ist das Motiv dort auch den Literaturwissenschafdem bekannt. Der Germanist H. Pyritz schrieb 1963 in seinem Buch uber den deutschen Lyriker Paul Fleming (1609-1640): "... lange fortwirkend in Flemings Dichtung ist ein . Motiv, das . zum eisemen Bestand der neulateinischen Poesie und aller ihrer volkssprachlichen Ableger gchort: der Gedanke von Scelenraub und Seelentausch im KuB."^ Jedoch ist Pyritz das Platon-Epigramm als Quelle unbekannt; er ziliert keine Belege fiir das Motiv vor dem Nicdcrlander Joannes Secundus (1511- 1536) und sieht anschcincnd in ihm seinen Urheber. Da die Literaturwissenschaftler der Gegenwart das Motiv, sofem sie es kennen, also zumindcst nicht immer als anlikes Motiv erkenncn und da insgesaml unbekannt zu sein scheint, auf welchem Weg dieses Motiv in die * S. -

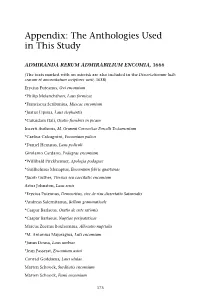

Appendix: the Anthologies Used in This Study

Appendix: The Anthologies Used in This Study ADMIRANDA RERUM ADMIRABILIUM ENCOMIA, 1666 (The texts marked with an asterisk are also included in the Dissertationum ludi- crarum et amoenitatum scriptores varii, 1638) Erycius Puteanus, Ovi encomium *Philip Melanchthon, Laus formicae *Franciscus Scribanius, Muscae encomium *Justus Lipsius, Laus elephantis *Cuiusdam Itali, Oratio funebris in picam Incerti Authoris, M. Grunnii Corocottae Porcelli Testamentum *Caelius Calcagnini, Encomium pulicis *Daniel Heinsius, Laus pediculi Girolamo Cardano, Podagrae encomium *Willibald Pirckheimer, Apologia podagrae *Guilhelmus Menapius, Encomium febris quartanae *Jacob Guther, Tiresias seu caecitatis encomium Artur Johnston, Laus senis *Erycius Puteanus, Democritus, sive de risu dissertatio Saturnalis *Andreas Salernitanus, Bellum grammaticale *Caspar Barlaeus, Oratio de ente rationis *Caspar Barlaeus, Nuptiae peripateticae Marcus Zuerius Boxhornius, Allocutio nuptialis *M. Antonius Majoragius, Luti encomium *Janus Dousa, Laus umbrae *Jean Passerat, Encomium asini Conrad Goddaeus, Laus ululae Marten Schoock, Surditatis encomium Marten Schoock, Fumi encomium 175 176 Appendix Mantissa, Itali cujusdam Authoris, Oratio funebris in gallum Thessalae mulieris; Oratio funebris in felem Florae viduae; Oratio funebris in canem Leonteum CASPAR DORNAU, AMPHITHEATRUM SAPIENTIAE SOCRATICAE IOCO-SERIAE, Vol. 2, 1619 (Only the texts used in my study) Aulus Gellius, Noctes Atticae (17.12, Thersites et quartana) Ulrich von Hutten, Febris prima et secunda Gulielmus Menapius -

The Light of Descartes in Rembrandts's Mature Self-Portraits

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 2020-03-19 The Light of Descartes in Rembrandts's Mature Self-Portraits Melanie Kathleen Allred Brigham Young University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Allred, Melanie Kathleen, "The Light of Descartes in Rembrandts's Mature Self-Portraits" (2020). Theses and Dissertations. 8109. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/8109 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. The Light of Descartes in Rembrandt’s Mature Self-Portraits Melanie Kathleen Allred A thesis submitted to the faculty of Brigham Young University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Martha Moffitt Peacock, Chair Elliott D. Wise James Russel Swensen Department of Comparative Arts and Letters Brigham Young University Copyright © 2020 Melanie Kathleen Allred All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The Light of Descartes in Rembrandt’s Mature Self-Portraits Melanie Kathleen Allred Department of Comparative Arts and Letters, BYU Master of Arts Rembrandt’s use of light in his self-portraits has received an abundance of scholarly attention throughout the centuries—and for good reason. His light delights the eye and captivates the mind with its textural quality and dramatic presence. At a time of scientific inquiry and religious reformation that was reshaping the way individuals understood themselves and their relationship to God, Rembrandt’s light may carry more intellectual significance than has previously been thought. -

The Emancipation of Biblical Philology in the Dutch Republic, 1590–1670

THE EMANCIPATION OF BIBLICAL PHILOLOGY IN THE DUTCH REPUBLIC, 1590–1670 The Emancipation of Biblical Philology in the Dutch Republic, 1590–1670 DIRK VAN MIERT 1 1 Great Clarendon Street, Oxford, OX2 6DP, United Kingdom Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries © Dirk van Miert 2018 The moral rights of the author have been asserted First Edition published in 2018 Impression: 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by licence or under terms agreed with the appropriate reprographics rights organization. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Data available Library of Congress Control Number: 2018938572 ISBN 978–0–19–880393–5 Printed and bound by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY Links to third party websites are provided by Oxford in good faith and for information only. -

A Man, an Age, a Book

MARCO FORLIVESI A Man, an Age, a Book 1. A man Bartolomeo Mastri was born in Meldola, near Forlì, on 7th December, 1602, into the lower aristocracy of the town. He en- tered the Order of Friars Minor Conventual in about 1616 and was educated at the Order’s studia in Cesena, Bologna, and Naples. After a brief period of teaching logic in the studia of the Order in Parma and Bologna, he completed his period as a stu- dent in the ‘Collegio di S. Bonaventura’ in Rome in the years 1625-1628. From 1628 to 1638 he was Regent, together with his fellow Brother Bonaventura Belluto from Catania, of the Order’s studia in Cesena and Perugia. In 1638 he was promoted, together with Belluto, to the post of Regent of the ‘Collegio di S. Antonio’ in Padua, a post he retained until 1641. From that year, which according to the customs of the time marked the end of his ca- reer as a teacher, until 1647 he resided alternately either in Mel- dola or Ravenna, a city where he held the post as private theolo- gian to Cardinal Luigi Capponi. In the meantime, together with Belluto, from 1628 to 1647 he planned, wrote and published his first great work: a cursus of Scotist philosophy articulated into logic, physics, and metaphysics. In 1647 he was elected Minister of his Order for the Province of Bologna. When this assignment was completed, in 1650, he returned to Meldola, where he lived until 1659 and compiled most of his theological works. From that year, until 1665, he was frequently a member of the retinue of the General Minister of his Order, Giacomo Fabretti from Ra- “Rem in seipsa cernere”.