Continuity and Rupture: Comparative Literature and the Latin Tradition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Banished to the Black Sea: Ovid's Poetic

BANISHED TO THE BLACK SEA: OVID’S POETIC TRANSFORMATIONS IN TRISTIA 1.1 A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of The School of Continuing Studies and of The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Liberal Studies By Christy N. Wise, M.A. Georgetown University Washington, D.C. October 16, 2014 BANISHED TO THE BLACK SEA: OVID’S POETIC TRANSFORMATIONS IN TRISTIA 1.1 Christy N. Wise, M.A. Mentor: Charles A. McNelis, Ph.D. ABSTRACT After achieving an extraordinarily successful career as an elegiac poet in the midst of the power, glory and creativity of ancient Rome during the start of the Augustan era, Ovid was abruptly separated from the stimulating community in which he thrived, and banished to the outer edge of the Roman Empire. While living the last nine or ten years of his life in Tomis, on the eastern shore of the Black Sea, Ovid steadily continued to compose poetry, producing two books of poems and epistles, Tristia and Epistulae ex Ponto, and a 644-line curse poem, Ibis, all written in elegiac couplets. By necessity, Ovid’s writing from relegatio (relegation) served multiple roles beyond that of artistic creation and presentation. Although he continued to write elegiac poems as he had during his life in Rome, Ovid expanded the structure of those poems to portray his life as a relegatus and his estrangement from his beloved homeland, thereby redefining the elegiac genre. Additionally, and still within the elegiac structure, Ovid changed the content of his poetry in order to defend himself to Augustus and request assistance from friends in securing a reduced penalty or relocation closer to Rome. -

The Intersection of Art and Ritual in Seventeenth-Century Dutch Visual Culture

Picturing Processions: The Intersection of Art and Ritual in Seventeenth-century Dutch Visual Culture By © 2017 Megan C. Blocksom Submitted to the graduate degree program in Art History and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Chair: Dr. Linda Stone-Ferrier Dr. Marni Kessler Dr. Anne D. Hedeman Dr. Stephen Goddard Dr. Diane Fourny Date Defended: November 17, 2017 ii The dissertation committee for Megan C. Blocksom certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Picturing Processions: The Intersection of Art and Ritual in Seventeenth-century Dutch Visual Culture Chair: Dr. Linda Stone-Ferrier Date Approved: November 17, 2017 iii Abstract This study examines representations of religious and secular processions produced in the seventeenth-century Northern Netherlands. Scholars have long regarded representations of early modern processions as valuable sources of knowledge about the rich traditions of European festival culture and urban ceremony. While the literature on this topic is immense, images of processions produced in the seventeenth-century Northern Netherlands have received comparatively limited scholarly analysis. One of the reasons for this gap in the literature has to do with the prevailing perception that Dutch processions, particularly those of a religious nature, ceased to be meaningful following the adoption of Calvinism and the rise of secular authorities. This dissertation seeks to revise this misconception through a series of case studies that collectively represent the diverse and varied roles performed by processional images and the broad range of contexts in which they appeared. Chapter 1 examines Adriaen van Nieulandt’s large-scale painting of a leper procession, which initially had limited viewership in a board room of the Amsterdam Leprozenhuis, but ultimately reached a wide audience through the international dissemination of reproductions in multiple histories of the city. -

Neo-Latin News

44 SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY NEWS NEO-LATIN NEWS Vol. 61, Nos. 1 & 2. Jointly with SCN. NLN is the official publica- tion of the American Association for Neo-Latin Studies. Edited by Craig Kallendorf, Texas A&M University; Western European Editor: Gilbert Tournoy, Leuven; Eastern European Editors: Jerzy Axer, Barbara Milewska-Wazbinska, and Katarzyna To- maszuk, Centre for Studies in the Classical Tradition in Poland and East-Central Europe, University of Warsaw. Founding Editors: James R. Naiden, Southern Oregon University, and J. Max Patrick, University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and Graduate School, New York University. ♦ Petrarch and St. Augustine: Classical Scholarship, Christian Theol- ogy and the Origins of the Renaissance in Italy. By Alexander Lee. Brill’s Studies in Intellectual History, 210. Leiden and Boston: Brill, 2012. x + 382 pp. $177. Petrarch’s opera is extensive, that of Augustine is extraordinarily vast, and the literature on both is vaster still. To bridge them successfully is a significant undertaking. Over the past fifty years, scholars have attempted this task, from classic studies by Charles Trinkaus (often discussed here) to more recent ones such as C. Quillen’s Rereading the Renaissance: Petrarch, Augustine and the Language of Humanism (1995) and M. Gill’s Augustine in the Italian Renaissance: Art and Philosophy from Petrarch to Michelangelo (2005). In a new study, Alexander Lee argues that “Petrarch’s thought on moral questions was derived principally from the writings of St. Augustine” (24). Lee contends that Petrarch, rather than being philosophically inconsistent as is often suggested, was especially influenced by Augustine’s early works, most notably the Soliloquies and the De vera religione, which provided him with an interpretive method for incorporating classical literature and philosophy into Christian moral theology. -

Orpheus and Eurydice in the Middle Books of the Faerie Queene The

Orpheus and Eurydice in the Middle Books of The Faerie Queene The commendatory sonnet by ‘W. S.’ appended to the first edition of The Faerie Queene hails Spenser as the ‘Brittayne Orpheus,’ and modern critics have thought the author was onto something. Thomas Cain in 1971 made the case that Spenser ‘use[s]...the Orpheus- figure to assert and assess his own role as poet’ across his works; more recently Patrick Cheney has talked about Spenser’s ‘Orphic career’.1 In Spenser criticism at large, the idea that Spenser wants to present himself as another Orpheus is frequently mentioned, though rarely discussed in much detail. Given all this attention to the importance of Orpheus in Spenser’s self-presentation, it is remarkable that an extremely curious feature of Spenser’s treatment of the Orpheus-myth has received so little comment, and its implications for our understanding of Spenser’s conception of his own role and powers remain unexplored. It concerns his treatment of Orpheus’ greatest exploit, his katabasis in the attempt to recover his wife Eurydice from the Underworld. In the version best known today, the episode ends in tragic failure: though Orpheus with his enchanting song succeeds in charming the gods of the Underworld to consent to Eurydice’s return, he breaks the condition imposed on him that he should not look back at her before they are both safely again in the upper world, and so loses her a second time, and irrevocably. Spenser refers to the myth several times across his works, but consistently presents Orpheus’ attempt as successful, and Eurydice as restored to life. -

The Reader and the Poet

THE READER AND THE POET THE TRANSFORMATION OF LATIN POETRY IN THE FOURTH CENTURY A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Aaron David Pelttari August 2012 i © 2012 Aaron David Pelttari ii The Reader and the Poet: The Transformation of Latin Poetry in the Fourth Century Aaron Pelttari, Ph.D. Cornell University 2012 In Late Antiquity, the figure of the reader came to play a central role in mediating the presence of the text. And, within the tradition of Latin poetry, the fourth century marks a turn towards writing that privileges the reader’s involvement in shaping the meaning of the text. Therefore, this dissertation addresses a set of problems related to the aesthetics of Late Antiquity, the reception of Classical Roman poetry, and the relation between author and reader. I begin with a chapter on contemporary methods of reading, in order to show the ways in which Late Antique authors draw attention to their own interpretations of authoritative texts and to their own creation of supplemental meaning. I show how such disparate authors as Jerome, Augustine, Servius, and Macrobius each privileges the work of secondary authorship. The second chapter considers the use of prefaces in Late Antique poetry. The imposition of paratextual borders dramatized the reader’s involvement in the text. In the third chapter, I apply Umberto Eco’s idea of the open text to the figural poetry of Optatianus Porphyrius, to the Psychomachia of Prudentius, and to the centos from Late Antiquity. -

The Humanist Discourse in the Northern Netherlands

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Clashes of discourses: Humanists and Calvinists in seventeenth-century academic Leiden Kromhout, D. Publication date 2016 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Kromhout, D. (2016). Clashes of discourses: Humanists and Calvinists in seventeenth- century academic Leiden. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:26 Sep 2021 Chapter 1: The humanist discourse in the Northern Netherlands This chapter will characterize the discourse of the Leiden humanists in the first decade of the seventeenth century. This discourse was in many aspects identical to the discourse of the Republic of Letters. The first section will show how this humanist discourse found its place at Leiden University through the hands of Janus Dousa and others. -

Introduction

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Clashes of discourses: Humanists and Calvinists in seventeenth-century academic Leiden Kromhout, D. Publication date 2016 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Kromhout, D. (2016). Clashes of discourses: Humanists and Calvinists in seventeenth- century academic Leiden. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:26 Sep 2021 Introduction Ill. 1: Pageant at the inauguration of Leiden University, Anonymous (1575) The inauguration of Leiden University on 8 February 1575 was a moment of great importance in the process of growing self-awareness in the Northern Netherlands. After a troublesome start, the Revolt was finally gaining momentum. It has often been debated whether the Dutch Revolt was a matter of money, government, or religion.2 The fact is that both nobility and the ruling class and a substantial proportion of the common people were not content with Philip II’s measures pertaining to all these areas. -

The Roots of Nationalism

HERITAGE AND MEMORY STUDIES 1 HERITAGE AND MEMORY STUDIES Did nations and nation states exist in the early modern period? In the Jensen (ed.) field of nationalism studies, this question has created a rift between the so-called ‘modernists’, who regard the nation as a quintessentially modern political phenomenon, and the ‘traditionalists’, who believe that nations already began to take shape before the advent of modernity. While the modernist paradigm has been dominant, it has been challenged in recent years by a growing number of case studies that situate the origins of nationalism and nationhood in earlier times. Furthermore, scholars from various disciplines, including anthropology, political history and literary studies, have tried to move beyond this historiographical dichotomy by introducing new approaches. The Roots of Nationalism: National Identity Formation in Early Modern Europe, 1600-1815 challenges current international scholarly views on the formation of national identities, by offering a wide range of contributions which deal with early modern national identity formation from various European perspectives – especially in its cultural manifestations. The Roots of Nationalism Lotte Jensen is Associate Professor of Dutch Literary History at Radboud University, Nijmegen. She has published widely on Dutch historical literature, cultural history and national identity. Edited by Lotte Jensen The Roots of Nationalism National Identity Formation in Early Modern Europe, 1600-1815 ISBN: 978-94-6298-107-2 AUP.nl 9 7 8 9 4 6 2 9 8 1 0 7 2 The Roots of Nationalism Heritage and Memory Studies This ground-breaking series examines the dynamics of heritage and memory from a transnational, interdisciplinary and integrated approaches. -

Illinois Classical Studies

27 Platons KuB und seine Folgen WALTHER LUDWIG "... when instantly Phoebe grew more composed, after two or three sighs, and heart-fetched Oh's! and giving me a kiss that seemed to exhale her soul through her lips, she replaced the bed-cloaths over us." John Cleland (1709-1789) laBt in seinen "Memoirs of a Woman of Pleasure" (zucrst gedruckt London 1749) Fanny Hill diese Erinnerungen aussprechen.' Nur wenigen Lesem des popularen Romans wird aufgefallen sein, daB die Vorstellung der Seele, die wahrend eines Kusses durch die Lippen zum Partner uberzugehen scheint, natiirlich direkt oder indirekt auf ein beriihmtes, bis ins 20. Jahrhundert Platon zugeschriebcnes Epigramm zuruckgeht, vielleicht direkt, da John Clclands Bildung durchaus ausreichte, um dieses Epigramm in seiner griechischen Originalform oder in eincr seiner lateinischen Obersetzungen zu kennen (er hatte ab 1722 die humanistisch orientierte Westminster School in London besucht und schrieb 1755 das Drama "Titus Vespasian" uber den romischen Kaiser), und sicher indirekt, da das Motiv langst in die neulateinische und nationalsprachliche Liebesdichtung eingegangen war. Grundsatzlich ist das Motiv dort auch den Literaturwissenschafdem bekannt. Der Germanist H. Pyritz schrieb 1963 in seinem Buch uber den deutschen Lyriker Paul Fleming (1609-1640): "... lange fortwirkend in Flemings Dichtung ist ein . Motiv, das . zum eisemen Bestand der neulateinischen Poesie und aller ihrer volkssprachlichen Ableger gchort: der Gedanke von Scelenraub und Seelentausch im KuB."^ Jedoch ist Pyritz das Platon-Epigramm als Quelle unbekannt; er ziliert keine Belege fiir das Motiv vor dem Nicdcrlander Joannes Secundus (1511- 1536) und sieht anschcincnd in ihm seinen Urheber. Da die Literaturwissenschaftler der Gegenwart das Motiv, sofem sie es kennen, also zumindcst nicht immer als anlikes Motiv erkenncn und da insgesaml unbekannt zu sein scheint, auf welchem Weg dieses Motiv in die * S. -

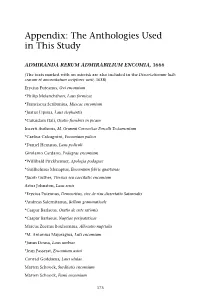

Appendix: the Anthologies Used in This Study

Appendix: The Anthologies Used in This Study ADMIRANDA RERUM ADMIRABILIUM ENCOMIA, 1666 (The texts marked with an asterisk are also included in the Dissertationum ludi- crarum et amoenitatum scriptores varii, 1638) Erycius Puteanus, Ovi encomium *Philip Melanchthon, Laus formicae *Franciscus Scribanius, Muscae encomium *Justus Lipsius, Laus elephantis *Cuiusdam Itali, Oratio funebris in picam Incerti Authoris, M. Grunnii Corocottae Porcelli Testamentum *Caelius Calcagnini, Encomium pulicis *Daniel Heinsius, Laus pediculi Girolamo Cardano, Podagrae encomium *Willibald Pirckheimer, Apologia podagrae *Guilhelmus Menapius, Encomium febris quartanae *Jacob Guther, Tiresias seu caecitatis encomium Artur Johnston, Laus senis *Erycius Puteanus, Democritus, sive de risu dissertatio Saturnalis *Andreas Salernitanus, Bellum grammaticale *Caspar Barlaeus, Oratio de ente rationis *Caspar Barlaeus, Nuptiae peripateticae Marcus Zuerius Boxhornius, Allocutio nuptialis *M. Antonius Majoragius, Luti encomium *Janus Dousa, Laus umbrae *Jean Passerat, Encomium asini Conrad Goddaeus, Laus ululae Marten Schoock, Surditatis encomium Marten Schoock, Fumi encomium 175 176 Appendix Mantissa, Itali cujusdam Authoris, Oratio funebris in gallum Thessalae mulieris; Oratio funebris in felem Florae viduae; Oratio funebris in canem Leonteum CASPAR DORNAU, AMPHITHEATRUM SAPIENTIAE SOCRATICAE IOCO-SERIAE, Vol. 2, 1619 (Only the texts used in my study) Aulus Gellius, Noctes Atticae (17.12, Thersites et quartana) Ulrich von Hutten, Febris prima et secunda Gulielmus Menapius -

PDF, Also Known As Version of Record

Edinburgh Research Explorer The representation and misrepresentation of Virgilian poetry in Propertius 2.34 Citation for published version: O'Rourke, D 2011, 'The representation and misrepresentation of Virgilian poetry in Propertius 2.34', American Journal of Philology, vol. 132, no. 3, pp. 457-497. https://doi.org/10.1353/ajp.2011.0030 Digital Object Identifier (DOI): 10.1353/ajp.2011.0030 Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Published In: American Journal of Philology Publisher Rights Statement: © O'Rourke, D. (2011). The representation and misrepresentation of Virgilian poetry in Propertius 2.34. American Journal of Philology, 132(3), 457-497. 10.1353/ajp.2011.0030 General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 23. Sep. 2021 The Representation and Misrepresentation of Virgilian Poetry in Propertius 2.34 Donncha O'Rourke American Journal of Philology, Volume 132, Number 3 (Whole Number 527), Fall 2011, pp. 457-497 (Article) Published by The Johns Hopkins University Press DOI: 10.1353/ajp.2011.0030 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/ajp/summary/v132/132.3.o-rourke.html Access provided by University of Edinburgh (26 Mar 2014 10:27 GMT) THE REPRESENTATION AND MISREPRESENTATION OF VIRGILIAN POETRY IN PROPERTIUS 2.34 DONNCHA O’ROURKE Abstract. -

Curriculum Vitae

Richard F. Thomas Curriculum Vitae Richard F. Thomas George Martin Lane Professor of the Classics Department of the Classics Harvard University 221 Boylston Hall Cambridge, MA 02138 (617) 496-6061 [email protected] EDUCATIONAL BACKGROUND B.A. Univ. of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, 1972 M.A. (1st Class Hons.) Univ. of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, 1973 Ph.D. Univ. of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan, 1977 TEACHING APPOINTMENTS Assistant Professor of Classics, Harvard University, 1977–82 Associate Professor of Classics, Harvard University, 1982–84 Associate Professor of Classics, University of Cincinnati, 1984–86 Professor of Classics, Cornell University, 1986–87 Professor of Greek and Latin, Harvard University, 1987–2011 Harvard College Professor 2009–14 George Martin Lane Professor of the Classics, 2011– Visiting Professor of Latin, University of Venice, May, 1991 TEACHING EXPERIENCE Graduate Seminars Roman Elegy, 1977; Greek and Roman Epigram, 1979; Virgil, Georgics, 1983, 1984, 1987; Livy, 1985; Virgil, Aeneid, 1986; Latin Palaeography, 1986; Roman Epyllion, 1987; Menander, 1990; Hellenistic Poetry, 1991; Roman Didactic 1992; Intertextuality and Genre 1993; Reception of Virgil, 1994; Callimachus from Alexandria to Rome, 1999, Greek and Latin Epigram and Elegy, 2001; Horace, Odes, 2002; Pastoral, 2005; Catullus, 2008; Virgil and Horace and their reception in the 17th and 18th centuries, 2010; Aesthetics in Hellenistic and Augustan Poetry, 2012, 2014; Tacitus, Annals 2015; Intertextuality and Reception from Alexandria to Rome and Beyond 2019 NEH Seminar for School Teachers Virgil's Aeneid, June/July, 1995 Advanced Latin Prose Composition 1978–2004, 2010 Upper-level undergraduate Greek and Latin courses Aristophanes, 1978; Livy, 1978; Horace, Odes and Epodes, 1975, 1985; Satires and Epistles, 1993, 1995, 1997, 2019; History of Latin Literature (beginnings to Aeneid) 1981, 1983, 1989, 1991; 1984–5; 1986–87, 1995, 1997, 1999, 2004 2018; Latin Lyric (Catullus and Horace), 1982, 1988; Hellenistic Poetry, 1983, 1988, 1991; August 12, 2020 1 Richard F.