Guide to Psychoanalytic Developmental Theories Joseph Palombo • Harold K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On Sigmund Freud

On Sigmund Freud I came across a wonderful book, “Fifty Thinkers Who Shaped the Modern World”, by Stephen Trombley. I have read a few of the chapter’s and found them insightful. I came across a chapter on Sigmund Freud. There is a wonderful biography of “Freud: A Life for our Time” by Peter Gay. Here are parts from the book that I found interesting. “Sigmund Freud is a member of the great triumvirate of revolutionary nineteenth-century thinkers that includes Charles Darwin and Karl Man Each provided a map of essential contours of the human situation Darwin offered a scientific explanation of how man evolved; Mall provided the theoretical tools for man to locate and create himself in an historical context; and Freud provided a guide to man's psyche, and an explanation of the dynamics of his psychology. Freud was a revolutionary because he led the way to overcoming taboos about sex by identifying human beings as essentially sexual.(It is impossible to imagine the 'sexual revolution' of the 1960s without Freud.) He posited the existence of the unconscious, a hitherto secret territory that influences our decisions, a place where secrets and unexpressed desires hide. But he also argued that analysis could reveal the workings of our unconscious. Along with Josef Breuer (1842-1925 and Alfred Adler (1870-1937) Freud was the founder of psychoanalysis. Freud was a prolific author, whose books and essays range from the theory of psychoanalysis to reflections on society and religion. His joint work with Breuer, Studies on Hysteria (1895), described hysteria as the proper object of psychoanalytic method. -

Psychoanalysis: Dream Including Freudian Symbolism Asst Prof

International Journal of English Literature and Social Sciences Vol-6, Issue-2; Mar-Apr, 2021 Journal Home Page Available: https://ijels.com/ Journal DOI: 10.22161/ijels Psychoanalysis: Dream including Freudian Symbolism Asst Prof. Aradhana Shukla Department of English, S.S.D.G.PG College Rudrapur, Udham Singh Nagar, Kumaun University, Nainital, Uttarakhand, India. Received: 06 Nov 2020; Received in revised form: 16 Jan 2021; Accepted: 06 Feb 2021; Available online: 06 Mar 2021 ©2021 The Author(s). Published by AI Publication. This is an open access article under the CC BY license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). Abstract— The initial acceptance of Psychoanalysis is the credence that all human posses memories, feelings, unconscious thoughts and desires. Jung felt that “The dream is a little hidden door in the innermost and most secret recesses of the psyche”. Some psychologists think that dreams are nothing more than the result of unplanned brain pursuit that take place when we are sleeping, while others acquire the perspective of human such as Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung that dreams can release a human's deepest unconscious wishes and desires. Keywords— Stimuli, Wish fulfillment, Regression, Infantile, Sigmund Freud, Carl Jung, Dream. I. INTRODUCTION theories, Freud experienced disturbing dreams, Sigmund Freud was born as Sigismund SchlComo Freud depression, and heart irregularities. He self-analyzed his (May 6, 1856), in the Moravian town of Freiberg in the dreams and memories of childhood. Some of his famous Austro- Hungarian Empire. He was the son of Jakob works are as follows- Freud and Amalia Nathanson. He studied philosophy • Studies on Hysteria (1895) which Freud co- under the German philosopher, Franz Brentano; authored with Josef Breuer and it described the physiology under Ernst Brucke; and Zoology under the evolution of his clinical methods. -

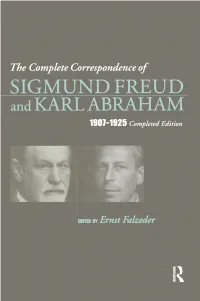

The Complete Correspondence of Sigmund Freud and Karl Abraham

THE COMPLETE CORRESPONDENCE OF SIGMUND FREUD AND KARL ABRAHAM THE COMPLETE CORRESPONDENCE OF SIGMUND FREUD AND KARL ABRAHAM 1 9 0 7 - 1 9 2 5 Completed Edition transcribed and edited by Ernst Falzeder translated by Caroline Schwarzacher with the collaboration of Christine Trollope & Klara Majthenyi King Introduction by Andre Haynal & Ernst Falzeder First published 2002 by H. Karnac (Books) Ltd. Published 2018 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN 52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Freud material copyright© 1965, 2002 by A. W. Freud et al. Abraham material copyright © 1965, 2002 by the Estate of Grant Allan Editorial material and annotations copyright © 2002 by Ernst Falzeder Introduction copyright © 2002 by Andre Haynal Translation copyright © 2002 by Caroline Schwarzacher Facsimiles of letters on pp. ii, 442, and 495 and photographs on pp. xxii, xxv, and 453 reproduced by courtesy of the Freud Museum by agreement with Sigmund Freud Coprights Ltd. A Psycho-Analytic Dialogue. The Letters of Sigmund Freud and Karl Abraham 1907-1926 (ed. Hilda C. Abraham and Ernst Freud). London: The Hogarth Press and The Institute of Psycho-Analysis, 1965. The rights of the authors, editor, and translator to be identified as the authors of this work have been asserted in accordance with §§ 77 and 78 of the Copyright Design and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

Five Formations of Publicity: Constitutive Rhetoric from Its Other Side

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF SPEECH, 2018 VOL. 104, NO. 2, 189–212 https://doi.org/10.1080/00335630.2018.1447140 Five formations of publicity: Constitutive rhetoric from its other side Jason D. Myres Communication Studies, University of Georgia, Athens, USA ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY This essay rethinks the constitutive formation of publics by Received 20 February 2017 foregrounding the desirability of publics themselves. This project Accepted 15 January 2018 begins by theoretically resituating publics as a series of KEYWORDS irrevocably lost objects. Specifically, I contend publics are Donald J. Trump; desire; composed of a montage of desires (oral, anal, phallic, scopic, and ’ public; prosopopeia; superego) modeled on Jacques Lacan s stages of the object in metonymy obsessional neurosis. To explicate, I use this schema to parse the symbolic dimensions of the “people” aligned with Donald J. Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign. Lacan’s schema of the object is adapted into a theory of publicity exemplified in the (astonishing) resilience of the “Trump voter,” the imaginary “people” routinely invoked throughout his emergence as a political figure. Lacan’s schema, I argue, helps explain the symbolic staging of the “Trump voter” as something more than just another potent social imaginary: an object of desire. Working from recent scholarship of Barbara Biesecker, Christian Lundberg, Joshua Gunn, and a growing number of others, this essay theorizes public formation from the standpoint of desire. However, I have a different emphasis in mind: rather than studying the for- mation of publics, I demarcate five potential con-formations of publicity that undergird publics as epiphenomena. This schema of desire refers not to a universal structure, but a partitioning that introduces difference within and between modes of public formation. -

Introduction: Jung, New York, 1912 Sonu Shamdasani

Copyrighted Material IntroductIon: Jung, neW York, 1912 Sonu Shamdasani September 28, 1912. the New York Times featured a full-page inter- view with Jung on the problems confronting america, with a por- trait photo entitled “america facing Its Most tragic Moment”— the first prominent feature of psychoanalysis in the Times. It was Jung, the Times correctly reported, who “brought dr. freud to the recognition of the older school of psychology.” the Times went on to say, “[H]is classrooms are crowded with students eager to under- stand what seems to many to be an almost miraculous treatment. His clinics are crowded with medical cases which have baffled other doctors, and he is here in america to lecture on his subject.” Jung was the man of the hour. aged thirty-seven, he had just com- pleted a five-hundred-page magnum opus, Transformations and Sym‑ bols of the Libido, the second installment of which had just appeared in print. following his first visit to america in 1909, it was he, and not freud, who had been invited back by Smith ely Jelliffe to lec- ture on psychoanalysis in the new international extension course in medicine at fordham university, where he would also be awarded his second honorary degree (others invited included the psychiatrist William alanson White and the neurologist Henry Head). Jung’s initial title for his lectures was “Mental Mechanisms in Health and disease.” By the time he got to composing them, the title had become simply “the theory of Psychoanalysis.” Jung com- menced his introduction to the lectures by indicating that he in- tended to outline his attitude to freud’s guiding principles, noting that a reader would likely react with astonishment that it had taken him ten years to do so. -

Sigmund Freud Papers

Sigmund Freud Papers A Finding Aid to the Papers in the Sigmund Freud Collection in the Library of Congress Digitization made possible by The Polonsky Foundation Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2015 Revised 2016 December Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms004017 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm80039990 Prepared by Allan Teichroew and Fred Bauman with the assistance of Patrick Holyfield and Brian McGuire Revised and expanded by Margaret McAleer, Tracey Barton, Thomas Bigley, Kimberly Owens, and Tammi Taylor Collection Summary Title: Sigmund Freud Papers Span Dates: circa 6th century B.C.E.-1998 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1871-1939) ID No.: MSS39990 Creator: Freud, Sigmund, 1856-1939 Extent: 48,600 items ; 141 containers plus 20 oversize and 3 artifacts ; 70.4 linear feet ; 23 microfilm reels Language: Collection material in German, with English and French Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Founder of psychoanalysis. Correspondence, holograph and typewritten drafts of writings by Freud and others, family papers, patient case files, legal documents, estate records, receipts, military and school records, certificates, notebooks, a pocket watch, a Greek statue, an oil portrait painting, genealogical data, interviews, research files, exhibit material, bibliographies, lists, photographs and drawings, newspaper and magazine clippings, and other printed matter. The collection documents many facets of Freud's life and writings; his associations with family, friends, mentors, colleagues, students, and patients; and the evolution of psychoanalytic theory and technique. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. -

Action and Reflection: the Emotional Dance Between Consultant and Client

Action and Reflection: The Emotional Dance between Consultant and Client _______________ Manfred F. R. KETS DE VRIES 2009/21/EFE/IGLC Action and Reflection: The Emotional Dance between Consultant and Client by Manfred F.R. Kets De Vries* * The Raoul de Vitry d’Avaucourt Clinical Professor of Leadership Development, Director, INSEAD Global Leadership Center (IGLC), INSEAD, France and Singapore. Ph: +33 1 60 72 41 55, Email: [email protected] A working paper in the INSEAD Working Paper Series is intended as a means whereby a faculty researcher's thoughts and findings may be communicated to interested readers. The paper should be considered preliminary in nature and may require revision. Printed at INSEAD, Fontainebleau, France. Kindly do not reproduce or circulate without permission. Executive Summary In this article, I explore subtle, mostly out-of-awareness dialogues between consultants and clients and highlight how consultants use themselves as an “instrument” when dealing with their clients—using their own reactions to help interpret what the client is trying to transmit to them. To deconstruct these dialogues, I touch on the meaning of transference and countertransference, processes originating from early mother-infant communication and essential to the ability “to listen with the third ear.” I discuss four types of transference-countertransference interface between consultant and client and identify the indicators to which consultants need to pay attention when dealing with their clients. I also explore dysfunctional communication patterns. 2 Behavior is a mirror in which every one displays his own image. —Johann Wolfgang von Goethe Language is surely too small a vessel to contain these emotions of mind and body that have somehow awakened a response in the spirit. -

The British Journal of Medical Psychology

Psychiatric Bulletin (1992), 16,28-29 The British Journal ofMedicalPsychology JOHN BIRTCHNELL (Current Editor) and SIDNEY CROWN (immediate past Editor) The British Journal of Medical Psychology is the During its 70 year history, the Journal has second most profitable ofthe eight specialist journals acquired considerable prominence, particularly for of the British Psychological Society and has an inter the part it has played in the development of psycho national circulation of around 2,300. It is unusual in analytic theory. In alphabetical order, some of its that it is the only one of the journals which is edited more notable contributors have been: Karl Abraham by a psychiatrist. While this has helped maintain (1923), Alfred Adler (1924), Mary Ainsworth (1951), valuable links between the professions ofpsychology Michael Argyle (1974), Michael Balint (several), and psychiatry, the BPS membership is becoming Don Bannister (1966), W. R. Bion (1949), John increasingly intolerant of this state of affairs. The Bowlby (1956, 1957 and 1958), Cyril Burt (1923, point is often made that the Royal College would 1926 and 1938), Alex Comfort (1977), Derek never sanction a psychologist editing one of its Russell Davis (several), Henry Dicks (several), Hans journals. We would like to believe that this is not Eysenck (several), Ronald Fairbairn (many), Sandor true. The procedure for the selection of new editors Ferenczi (1928), Michael Fordham (several), was recently modified to make it less likely that a Graham Foulds (1973), S. H. Foulkes (several), psychiatrist will be appointed next time. Some may Thomas Freeman (several), Edward Glover (sever regret such a development, while others may con al), Bob Gosling (1978), George Groddeck (1929 and sider it only right that what may be perceived as a 1931), H. -

Karen Horney Vs. Sigmund Freud

Karen Horney vs. Sigmund Freud: Breaking Barriers in Psychoanalysis for Women as a Woman Cate Boyette Individual Performance Senior Division Process Paper: 492 words Boyette 1 Last summer, I was a volunteer at a coding camp for gifted, disadvantaged elementary school girls. At the camp, we used a book titled Women in Science-- 50 Fearless Pioneers Who Changed the World. After doing National History Day for two years, I knew I wanted to do it again, and I was on the lookout for topics to fit the theme of Breaking Barriers in History. After I read the excerpt on Karen Horney, I immediately knew I wanted to tell her story. The way she challenged Freudian beliefs for having both misogynistic and scientific flaws during a time when promoting such ideas could ruin one’s reputation as a psychoanalyst clearly broke barriers. She also paved the way for women who wanted to pursue psychoanalysis and specialize in adult therapy. Because my topic this year was more academic in nature, my research process differed from previous years. I immediately noticed that primary sources were easier to find, especially medical articles, journals from the time, and the works of Horney and other psychoanalysts. My most useful primary sources were the two books by Horney. I used Feminine Psychology to explain her counter-argument to Freud´s popular theory on the castration complex in women and I used Neurosis and Human Growth to discuss her anti-Freudian beliefs. What was difficult to find were high-quality secondary sources. Since most of my primary sources focused on particular aspects of Horney's life, I tried looking for a biography. -

FROM FEMININE SEXUALITY to JOUISSANCE AS SUCH Silvia Tendlarz

EXPRESS DECEMBER 2017 VOLUME 3 - ISSUE 12 THE MIRACLE OF LOVE: FROM FEMININE SEXUALITY TO JOUISSANCE AS SUCH SILVIA TENDLARZ The LC EXPRESS delivers the Lacanian Compass in a new format. Its aim is to deliver relevant texts in a dynamic timeframe for use in the clinic and in advance of study days and conference meetings. The LC EXPRESS publishes works of theory and clinical practice and emphasizes both longstanding concepts of the Lacanian tradition as well as new cutting edge formulations. lacaniancompass.com PRÉCIS On Wednesday, July 22, 2015 New York Freud lover is the one who doesn’t have and doesn’t know Lacan Analytic Group (now Lacanian Compass) what is missing, and the loved one has, but doesn’t presented a lecture by Silvia Tendlarz. Held at the know what he or she has.” Continuing to Seminar X, CUNY Graduate Center’s Department of Psycholo- Tendlarz highlighted love as a mediation between gy, the presentation culminated a month-long sum- jouissance and desire. This mediation exposed the mer program dedicated to readings from Jacques- antimony between an autoerotic jouissance and Alain Miller’s course, The Experience of the Real in desire which reaches towards the Other. Psychoanalysis. The second part of the talk, titled “The Tempta- Opening with the biblical creation of Eve from tion of Desire,” examined the different dialectics the rib of Adam, Tendlarz began her inquiry into of desire operating in the masculine and feminine feminine jouissance, masculine jouissance, and subjective positions. In the feminine position, “de- jouissance of the body beyond the Oedipal frame. -

The Jewish Psychologists from Sigmund Freud to Dr

The Jewish Psychologists From Sigmund Freud to Dr. Ruth Is Psychology a “Jewish Thing?” • According to the Review of General Psychology 2002 40% of the most frequently cited researchers were Jewish. • Most of the key early psychologists were Jews – Sigmund and Anna Freud, Alfred Adler, Erik Erikson, Erich Fromm, Abraham Maslow, etc. • Exception – Carl Jung • Theories about Jewish sensitivity - Mark Zborowski. • Ties to Rabbinic Judaism. Larry’s Theory Cultural and Historical influences taking place in and around Germany and Austria at a crucial period influenced a group of people to start analyzing the human mind in new ways. The early stages leading to the development of psychology should not be separated from Nazism. It was THE major influence impacting the early social psychologists. Not only do historical records support this point of view, the writings of the people involved show their concerns. What Is Psychology? • The science of the mind and of behavior. • Originally a branch of religion, psyche meaning “breath (or) spirit (or) soul.” • 16th Century the term is used by German theologian Philip Melanchthon. The mind cannot be separated from the soul. • Later it becomes the study of illness that cannot be explained by physical analysis. • Clinical, educational, cognitive, forensic, social, developmental – branches. What is Jewish Culture? • High value on learning • Separation from gentiles • Endogamy (marrying within the group) • High investment in children. • Relatively strong roles for women. • Haskalah – Jewish enlightenment brings change Enter Freud • “I was born on May 6, 1856 at Frieberg in Moravia, a small town in what is now Czechoslovakia. My parents were Jews, and I have remained a Jew myself.” • Father is Jacob, mother is Amalia. -

Freud, Censorship and the Re-Territorialization of Mind

BJHS 45(2): 235–266, June 2012. © The Author(s) (2012) Published by The British Society for the History of Science and Cambridge University Press doi:10.1017/S000708741200009X Blacked-out spaces: Freud, censorship and the re-territorialization of mind PETER GALISON* Abstract. Freud’s analogies were legion: hydraulic pipes, military recruitment, magic writing pads. These and some three hundred others took features of the mind and bound them to far-off scenes – the id only very partially resembles an uncontrollable horse, as Freud took pains to note. But there was one relation between psychic and public act that Freud did not delimit in this way: censorship, the process that checked memories and dreams on their way to the conscious. (Freud dubbed the relation between internal and external censorship a ‘parallel’ rather than a limited analogy.) At first, Freud likened this suppression to the blacking out of texts at the Russian frontier. During the First World War, he suffered, and spoke of suffering under, Viennese postal and newspaper censorship – Freud was forced to leave his envelopes unsealed, and to recode or delete content. Over and over, he registered the power of both internal and public censorship in shared form: distortion, anticipatory deletion, softenings, even revision to hide suppression. Political censorship left its mark as the conflict reshaped his view of the psyche into a society on a war footing, with homunculus-like border guards sifting messages as they made their way – or did not – across a topography of mind. Caviar, sex and death Censorship came early and often to Vienna.