A Short Study of the Development of the Libido, Viewed in the Light of Mental Disorders (1924) 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Slave for Two Masters: Countertransference of a Wounded

A Slave For Two Masters: Countertransference of a Wounded Healer in the Treatment of a “Difficult to Treat” Adolescent by Ralph Cuseglio A case study submitted to the School of Social Work Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Social Work Graduate Program in Social Work New Brunswick, New Jersey October 2015 A Slave For Two Masters: Countertransference of a Wounded Healer in the Treatment of a “What is to give light must endure burning.” “Difficult to Treat” Adolescent -Viktor Frankl Ralph Cuseglio The referral seemed straightforward enough, a “softball,” I thought. A woman named Ruth called Abstract my office seeking counseling for her fifteen-year- The aim of this case study is to analyze intense old son. He’d recently returned home, blackout countertransference experienced by a therapist drunk after his girlfriend ended their three-month while treating a “difficult to treat” adolescent relationship. Teenage breakup was a subject with patient. During treatment, the therapist struggled which I had become quite familiar. Having worked to recognize much of his subjective with hundreds of teens, I had listened to countless countertransference and its impact on the tales of woe. Lending an ear and the passage of treatment. This paper will discuss the reasons for time was usually enough to mend the young heart. this and the manner in which both subjective and Not this time. And that softball…well, it clocked objective countertransference played a role. In me upside my head and brought me to my knees. doing so, the therapist discusses how his This paper has arisen out of a desire to childhood experiences and the subsequent understand the countertransference reactions I assumption of Carl Jung’s wounded healer experienced while working with the archetype fueled the countertransference in ways aforementioned patient; most of which came in that were concurrently beneficial and detrimental hindsight long after treatment ended. -

Mapsychology113.Pdf

DEPARTMENT OF PSYCHOLOGY PATNA UNIVERSITY, PATNA Advance General Psychology, sem-1st Ranjeet Kumar Ranjan Assistant Professor (Part Time) [email protected] Mob. No.-6203743650 PERSONALITY Personality is an individual’s unique and relatively stable patterns of behavior, thoughts, and emotions. FREUD’S THEORY OF PERSONALITY Freud defined personality in four central points i.e., levels of consciousness, the structure of personality, anxiety and defense mechanism, and psychosexual stages of development. Psychosexual stages Oral Stage – The first stage is the oral stage. An infant is in this stage from birth to eighteen months of age. The main focus in the oral stage is pleasure seeking through the infant’s mouth. During this stage, the need for tasting and sucking becomes prominent in producing pleasure. Oral stimulation is crucial during this stage; if the infant’s needs are not met during this time frame he or she will be fixated in the oral stage. Fixation in this stage can lead to adult habits such as thumb-sucking, smoking, over-eating, and nail-biting. Personality traits can also develop during adulthood that are linked to oral fixation; these traits can include optimism and independence or pessimism and hostility. Anal Stage – The second stage is the anal stage which lasts from eighteen months to three years of age. During this stage the infant’s pleasure seeking centers are located in the bowels and bladder. Parents stress toilet training and bowel control during this time period. Fixation in the anal stage can lead to anal-retention or anal- expulsion. Anal retentive characteristics include being overly neat, precise, and orderly while being anal expulsive involves being disorganized, messy, and destructive. -

Classical Psychoanalysis Psikologi Kepribadian

Classical Psychoanalysis Psikologi Kepribadian Rizqy Amelia Zein 2017-09-14 1 / 67 [1] Image credit: Giphy 2 / 67 Classical Psychoanalysis [...also known as Ego Psychology, Psychodynamics] 3 / 67 First things rst: Instinct! 4 / 67 Instincts (1) Freud denes it as the motivating forces that drive behaviour and determine its direction. Instinct (or Trieb in German), is a form of energy, that is transformed into physical energy and serve its function to connect the physical and psychological needs. Freud argues that human always experience instinctual tension and unable to escape from it. So most of our activities are directed to reduce this tension. People could have different ways to reduce the tension (e.g. sexual drives can manifest in various sexual behaviours). It's also possible to substitute the objects (displacement) and this process is primarily important to determine one's behaviour. Freud coined the terms "life" and "death" instincts, which posit different process of primal motivations. 11 / 67 Instincts (2) The Life Instinct 1. Serve the purpose of survival of the individual and the species by seeking to satisfy the needs for food, water, air, and sex. 2. The life instincts are oriented toward growth and development. The psychic energy manifested by the life instincts is the libido. 3. The libido can be attached to or invested in objects, a concept Freud called cathexis. 4. So if you like Ryan Gosling so much, for example, then your libido is cathected to him. 12 / 67 Instincts (2) The Death Instinct 1. In opposition to the life instincts, Freud postulated the destructive or death instincts. -

Theory and Practice of Counseling and Psychotherapy

ninth edition Theory and Practice of Counseling and Psychotherapy GERALD COREY California State University, Fullerton Diplomate in Counseling Psychology American Board of Professional Psychology $XVWUDOLDä%UD]LOä-DSDQä.RUHDä0H[LFRä6LQJDSRUHä6SDLQä8QLWHG.LQJGRPä8QLWHG6WDWHV Copyright 2011 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. May not be copied, scanned, or duplicated, in whole or in part. Due to electronic rights, some third party content may be suppressed from the eBook and/or eChapter(s). Editorial review has deemed that any suppressed content does not materially affect the overall learning experience. Cengage Learning reserves the right to remove additional content at any time if subsequent rights restrictions require it. About the Author GERALD COREY is a Professor Emeritus of Human Serv- ices at California State University at Fullerton and a licensed psychologist. He received his doctorate in counseling from the University of Southern California. He is a Diplomate in Counseling Psychology, American Board of Professional Psychology; a National Certified Counselor; a Fellow of the American Psychological Association (Counseling Psychol- ogy); a Fellow of the American Counseling Association; and Associated Press a Fellow of the Association for Specialists in Group Work. He also holds memberships in the American Group Psycho- therapy Association; the American Mental Health Counselors Association; the As- sociation for Spiritual, Ethical, and Religious Values in Counseling; the Associa- tion for Counselor Education and Supervision; and the Western Association for Coun selor Education and Supervision. Along with Marianne Schneider Corey, Jerry received the Lifetime Achieve- ment Award from the American Mental Health Counselors Association in 2011 and the Eminent Career Award from the Association for Specialists in Group Work in 2001. -

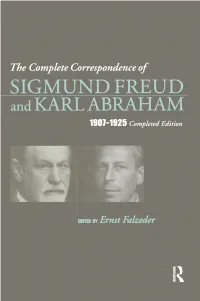

The Complete Correspondence of Sigmund Freud and Karl Abraham

THE COMPLETE CORRESPONDENCE OF SIGMUND FREUD AND KARL ABRAHAM THE COMPLETE CORRESPONDENCE OF SIGMUND FREUD AND KARL ABRAHAM 1 9 0 7 - 1 9 2 5 Completed Edition transcribed and edited by Ernst Falzeder translated by Caroline Schwarzacher with the collaboration of Christine Trollope & Klara Majthenyi King Introduction by Andre Haynal & Ernst Falzeder First published 2002 by H. Karnac (Books) Ltd. Published 2018 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN 52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017 Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business Freud material copyright© 1965, 2002 by A. W. Freud et al. Abraham material copyright © 1965, 2002 by the Estate of Grant Allan Editorial material and annotations copyright © 2002 by Ernst Falzeder Introduction copyright © 2002 by Andre Haynal Translation copyright © 2002 by Caroline Schwarzacher Facsimiles of letters on pp. ii, 442, and 495 and photographs on pp. xxii, xxv, and 453 reproduced by courtesy of the Freud Museum by agreement with Sigmund Freud Coprights Ltd. A Psycho-Analytic Dialogue. The Letters of Sigmund Freud and Karl Abraham 1907-1926 (ed. Hilda C. Abraham and Ernst Freud). London: The Hogarth Press and The Institute of Psycho-Analysis, 1965. The rights of the authors, editor, and translator to be identified as the authors of this work have been asserted in accordance with §§ 77 and 78 of the Copyright Design and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. -

Five Formations of Publicity: Constitutive Rhetoric from Its Other Side

QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF SPEECH, 2018 VOL. 104, NO. 2, 189–212 https://doi.org/10.1080/00335630.2018.1447140 Five formations of publicity: Constitutive rhetoric from its other side Jason D. Myres Communication Studies, University of Georgia, Athens, USA ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY This essay rethinks the constitutive formation of publics by Received 20 February 2017 foregrounding the desirability of publics themselves. This project Accepted 15 January 2018 begins by theoretically resituating publics as a series of KEYWORDS irrevocably lost objects. Specifically, I contend publics are Donald J. Trump; desire; composed of a montage of desires (oral, anal, phallic, scopic, and ’ public; prosopopeia; superego) modeled on Jacques Lacan s stages of the object in metonymy obsessional neurosis. To explicate, I use this schema to parse the symbolic dimensions of the “people” aligned with Donald J. Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign. Lacan’s schema of the object is adapted into a theory of publicity exemplified in the (astonishing) resilience of the “Trump voter,” the imaginary “people” routinely invoked throughout his emergence as a political figure. Lacan’s schema, I argue, helps explain the symbolic staging of the “Trump voter” as something more than just another potent social imaginary: an object of desire. Working from recent scholarship of Barbara Biesecker, Christian Lundberg, Joshua Gunn, and a growing number of others, this essay theorizes public formation from the standpoint of desire. However, I have a different emphasis in mind: rather than studying the for- mation of publics, I demarcate five potential con-formations of publicity that undergird publics as epiphenomena. This schema of desire refers not to a universal structure, but a partitioning that introduces difference within and between modes of public formation. -

Psychoanalytic Theory

Please purchase PDFcamp Printer on http://www.verypdf.com/ to remove this watermark. Psychoanalytic Theory Theories of counseling- OMC 18th January, 2011 Please purchase PDFcamp Printer on http://www.verypdf.com/ to remove this watermark. Dr Sigmund Freud 1856-1939 n Oldest of eight children n Married with 3 girls and 3 boys n Physician-Biologist – Scientific oriented and Pathology oriented theory n Jewish-anti-religion-All religion an illusion used to cope with feelings of infantile helplessness n In Vienna Austria 78 years till 1938 n Based theory on personal experiences n Died of cancer of jaw & mouth lifelong cigar chain-smoker Please purchase PDFcamp Printer on http://www.verypdf.com/ to remove this watermark. Freud’s Psychoanalytic Approach: n Model of personality development n Philosophy of Human Nature n Method of Psychotherapy n Identified dynamic factors that motivate behavior n Focused on role of unconscious n Developed first therapeutic procedures for understanding & modifying structure of one’s basic character Please purchase PDFcamp Printer on http://www.verypdf.com/ to remove this watermark. Determinism n Freud’s perspective n Behavior is determined by n Irrational forces n Unconscious motivations n Biological and instinctual drives as they evolve through the six psychosexual stages of life Please purchase PDFcamp Printer on http://www.verypdf.com/ to remove this watermark. Instincts n Libido – sexual energy – survival of the individual and human race- oriented towards growth, development & creativity – Pleasure principle – goal of life gain pleasure and avoid pain n Death instinct – accounts for aggressive drive – to die or to hurt themselves or others n Sex and aggressive drives- powerful determinants of peoples actions Please purchase PDFcamp Printer on http://www.verypdf.com/ to remove this watermark. -

Introduction: Jung, New York, 1912 Sonu Shamdasani

Copyrighted Material IntroductIon: Jung, neW York, 1912 Sonu Shamdasani September 28, 1912. the New York Times featured a full-page inter- view with Jung on the problems confronting america, with a por- trait photo entitled “america facing Its Most tragic Moment”— the first prominent feature of psychoanalysis in the Times. It was Jung, the Times correctly reported, who “brought dr. freud to the recognition of the older school of psychology.” the Times went on to say, “[H]is classrooms are crowded with students eager to under- stand what seems to many to be an almost miraculous treatment. His clinics are crowded with medical cases which have baffled other doctors, and he is here in america to lecture on his subject.” Jung was the man of the hour. aged thirty-seven, he had just com- pleted a five-hundred-page magnum opus, Transformations and Sym‑ bols of the Libido, the second installment of which had just appeared in print. following his first visit to america in 1909, it was he, and not freud, who had been invited back by Smith ely Jelliffe to lec- ture on psychoanalysis in the new international extension course in medicine at fordham university, where he would also be awarded his second honorary degree (others invited included the psychiatrist William alanson White and the neurologist Henry Head). Jung’s initial title for his lectures was “Mental Mechanisms in Health and disease.” By the time he got to composing them, the title had become simply “the theory of Psychoanalysis.” Jung com- menced his introduction to the lectures by indicating that he in- tended to outline his attitude to freud’s guiding principles, noting that a reader would likely react with astonishment that it had taken him ten years to do so. -

Sigmund Freud Papers

Sigmund Freud Papers A Finding Aid to the Papers in the Sigmund Freud Collection in the Library of Congress Digitization made possible by The Polonsky Foundation Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2015 Revised 2016 December Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/mss.contact Additional search options available at: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.mss/eadmss.ms004017 LC Online Catalog record: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm80039990 Prepared by Allan Teichroew and Fred Bauman with the assistance of Patrick Holyfield and Brian McGuire Revised and expanded by Margaret McAleer, Tracey Barton, Thomas Bigley, Kimberly Owens, and Tammi Taylor Collection Summary Title: Sigmund Freud Papers Span Dates: circa 6th century B.C.E.-1998 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1871-1939) ID No.: MSS39990 Creator: Freud, Sigmund, 1856-1939 Extent: 48,600 items ; 141 containers plus 20 oversize and 3 artifacts ; 70.4 linear feet ; 23 microfilm reels Language: Collection material in German, with English and French Location: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Summary: Founder of psychoanalysis. Correspondence, holograph and typewritten drafts of writings by Freud and others, family papers, patient case files, legal documents, estate records, receipts, military and school records, certificates, notebooks, a pocket watch, a Greek statue, an oil portrait painting, genealogical data, interviews, research files, exhibit material, bibliographies, lists, photographs and drawings, newspaper and magazine clippings, and other printed matter. The collection documents many facets of Freud's life and writings; his associations with family, friends, mentors, colleagues, students, and patients; and the evolution of psychoanalytic theory and technique. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. -

The University of Sheffield Object

The University of Sheffield Object Relations Middle Group and Attachment Theory: Gender Development, Spousal Abuse, and Qualitative Research On Youth Crime s. S. Wier PhD Object Relations Middle Group and Attachment Theory: Gender Development, Spousal Abuse, and Qualitative Research on Youth Crime Stewart Scott Wier PhD Centre for Psychotherapeutic Studies January 2003 Acknowledgments There are a number of people to whom I wish to express my sincere thanks and appreciation for their role in facilitating this achievement. Dr. Don Carveth first introduced me to the subject of psychoanalytic thought. He encouraged me to develop the potential he saw as an undergraduate student, and has continued to do so over the years, the most recent being through his endorsement of this particular dream. Dr. Gottfried Paasche is responsible for acquainting me with the process of qualitative methods of research, around which much of this paper is based, as well as for sponsoring my application to pursue this endeavor. The initial efforts for this project began over a decade ago at the University of Exeter under the direction of Dr. Paul Kline. He provided outstanding support and optimism surrounding these labours, in addition to showing compassion about my eventual decision to suspend them. Several years later, and following the retirement of Dr. Kline, Dr. Robert Young ofthe University of Sheffield, willingly assumed the responsibility ofacting as my subsequent supervisor despite the enormous demands on his time. The chair of the department for Psychotherapeutic Studies, Geraldine Shipton, displayed integrity, moral commitment, and consistency throughout the entire process. Dr. Christopher Cordess and Dr. Corinne Squire provided informed and respectful critical comments through a very cordial session which served to make a potentially distressing experience exceedingly pleasant, and brought considerable improvement to the first effort. -

Major Approaches to Psychology Part I the Ubiquity of Freudian Theory In

9.00 Introduction to Psychology – Fall 2001 Prof. Steven Pinker Week 2, Lecture 1: Major Approaches to Psychology I: Freud & Skinner The Ubiquity of Freudian Theory in Everyday Life • “He drives that Corvette because it’s really phallic” Major Approaches to Psychology • “My roommate is busy alphabetizing her shirts. She’s so anal!” Part I • “His mother is really domineering. No wonder he’s so screwed up.” The Psychoanalytic (Freudian) • “She’s unhappy because she’s so uptight and Approach repressed.” • “If only Mel had an outlet so that he could vent his hostility and channel it into more productive activities, he wouldn’t have shot up the post office with an Uzi.” Sigmund Freud • Some biographical facts. 1856-1939. • Background in neurology: – Aphasia – Hypnosis – Cocaine 1 9.00 Introduction to Psychology – Fall 2001 Prof. Steven Pinker Week 2, Lecture 1: Major Approaches to Psychology I: Freud & Skinner Sigmund Freud, continued Components of Freudian Theory • Radical themes: • 1. Psychic energy (The hydraulic model) – Unconscious mind – Libido – Irrationality – Sexuality – Repression – Hidden conflict – Importance of childhood – Lack of accidents • Comparison with Copernicus, Darwin Components of Freudian The Id (“it”) Theory, continued • The pleasure principle: Gratification of desire. • Primary process thinking. • 2. The Structural Theory – Infancy – Superego – Dreams • House = body – Ego • King & Queen = mom & dad – Id • Children = genitals • Playing with children = ... • Journey = death • Stairs = sex • Bath = birth – “Freudian Slips” – Free association – Psychosis 2 9.00 Introduction to Psychology – Fall 2001 Prof. Steven Pinker Week 2, Lecture 1: Major Approaches to Psychology I: Freud & Skinner Primary process thinking of the Structural theory, cont.: Id, continued 2. -

A Historical Review of Disgust

Modern Psychological Studies Volume 5 Number 2 Article 2 1997 A historical review of disgust Amanda Burlington University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Chad McDaniel University of Tennessee at Chattanooga David O. Wilson University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.utc.edu/mps Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Burlington, Amanda; McDaniel, Chad; and Wilson, David O. (1997) "A historical review of disgust," Modern Psychological Studies: Vol. 5 : No. 2 , Article 2. Available at: https://scholar.utc.edu/mps/vol5/iss2/2 This articles is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals, Magazines, and Newsletters at UTC Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Modern Psychological Studies by an authorized editor of UTC Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A Historical Review of Disgust Amanda Burlingham, Chad McDaniel, and David 0. Wilson PhD. University of Tennessee at Chattanooga Although disgust was identified as a basic emotion 125 years ago (Darwin, 1965), no psychological theory has focused on disgust as a key concept. Although many prominent scientists such as Freud, Darwin, and Ma/son have addressed the topic of disgust in their research, none have focused solely on the causes and consequences of disgust. The purpose of this paper is to evaluate the literature concerning disgust and to demonstrate how disgust is a meaningful concept worthy of major focus in psychological research, theories, and application. Disgust has never been a major focal point of Psychoanalytic View of Disgust psychological research. Although disgust was identified as a basic emotion 125 years ago (Darwin, Freud viewed disgust as a reaction-formation, 1872/1965), no psychological theory has focused on and thus in the psychoanalytic framework, disgust disgust as a key concept.