Experimental Philosophy, Robert Kane, and the Concept of Free Will

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Forthcoming in Oxford Studies in Experimental Philosophy Causal Reasoning

Forthcoming in Oxford Studies in Experimental Philosophy Causal Reasoning: Philosophy and Experiment* James Woodward History and Philosophy of Science University of Pittsburgh 1. Introduction The past few decades have seen much interesting work, both within and outside philosophy, on causation and allied issues. Some of the philosophy is understood by its practitioners as metaphysics—it asks such questions as what causation “is”, whether there can be causation by absences, and so on. Other work reflects the interests of philosophers in the role that causation and causal reasoning play in science. Still other work, more computational in nature, focuses on problems of causal inference and learning, typically with substantial use of such formal apparatuses as Bayes nets (e.g. , Pearl, 2000, Spirtes et al, 2001) or hierarchical Bayesian models (e.g. Griffiths and Tenenbaum, 2009). All this work – the philosophical and the computational -- might be described as “theoretical” and it often has a strong “normative” component in the sense that it attempts to describe how we ought to learn, reason, and judge about causal relationships. Alongside this normative/theoretical work, there has also been a great deal of empirical work (hereafter Empirical Research on Causation or ERC) which focuses on how various subjects learn causal relationships, reason and judge causally. Much of this work has been carried out by psychologists, but it also includes contributions by primatologists, researchers in animal learning, and neurobiologists, and more rarely, philosophers. In my view, the interactions between these two groups—the normative/theoretical and the empirical -- has been extremely fruitful. In what follows, I describe some ideas about causal reasoning that have emerged from this research, focusing on the “interventionist” ideas that have figured in my own work. -

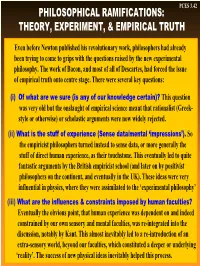

Philosophical Ramifications: Theory, Experiment, & Empirical Truth

PCES 3.42 PHILOSOPHICAL RAMIFICATIONS: THEORY, EXPERIMENT, & EMPIRICAL TRUTH Even before Newton published his revolutionary work, philosophers had already been trying to come to grips with the questions raised by the new experimental philosophy. The work of Bacon, and most of all of Descartes, had forced the issue of empirical truth onto centre stage. There were several key questions: (i) Of what are we sure (is any of our knowledge certain)? This question was very old but the onslaught of empirical science meant that rationalist (Greek- style or otherwise) or scholastic arguments were now widely rejected. (ii) What is the stuff of experience (Sense data/mental ‘impressions’). So the empiricist philosophers turned instead to sense data, or more generally the stuff of direct human experience, as their touchstone. This eventually led to quite fantastic arguments by the British empiricist school (and later on by positivist philosophers on the continent, and eventually in the UK). These ideas were very influential in physics, where they were assimilated to the ‘experimental philosophy’ (iii) What are the influences & constraints imposed by human faculties? Eventually the obvious point, that human experience was dependent on and indeed constrained by our own sensory and mental faculties, was re-integrated into the discussion, notably by Kant. This almost inevitably led to a re-introduction of an extra-sensory world, beyond our faculties, which constituted a deeper or underlying ‘reality’. The success of new physical ideas inevitably helped this process. PCES 3.43 BRITISH EMPIRICISM I: Locke & “Sensations” Locke was the first British philosopher of note after Bacon; his work is a reaction to the European rationalists, and continues to elaborate ‘experimental philosophy’. -

Experimental Philosophy Jordan Kiper, Stephen Stich, H. Clark Barrett

Experimental Philosophy Jordan Kiper, Stephen Stich, H. Clark Barrett, & Edouard Machery Kiper, J., Stich, S., Barrett, H.C., & Machery, E. (in press). Experimental philosophy. In D. Ludwig, I. Koskinen, Z. Mncube, L. Poliseli, & L. Reyes-Garcia (Eds.), Global Epistemologies and Philosophies of Science. New York, NY: Routledge. Acknowledgments: This publication was made possible through the support of a grant from the John Templeton Foundation. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the John Templeton Foundation. Abstract Philosophers have argued that some philosophical concepts are universal, but it is increasingly clear that the question of philosophical universals is far from settled, and that far more cross- cultural research is necessary. In this chapter, we illustrate the relevance of investigating philosophical concepts and describe results from recent cross-cultural studies in experimental philosophy. We focus on the concept of knowledge and outline an ongoing project, the Geography of Philosophy Project, which empirically investigates the concepts of knowledge, understanding, and wisdom across cultures, languages, religions, and socioeconomic groups. We outline questions for future research on philosophical concepts across cultures, with an aim towards resolving questions about universals and variation in philosophical concepts. 1 Introduction For centuries, thinkers have urged that fundamental philosophical concepts, such as the concepts of knowledge or right and wrong, are universal or at least shared by all rational people (e.g., Plato 1892/375 BCE; Kant, 1998/1781; Foot, 2003). Yet many social scientists, in particular cultural anthropologists (e.g., Boas, 1940), but also continental philosophers such as Foucault (1969) have remained skeptical of these claims. -

Experimental Philosophy and the Compatibility of Free Will and Determinism: a Survey

Annals of the Japan Association for Philosophy of Science Vol.22 (2014) 17~37 17 Experimental Philosophy and the Compatibility of Free Will and Determinism: A Survey Florian Cova∗ and Yasuko Kitano∗∗ Abstract The debate over whether free will and determinism are compatible is con- troversial, and produces wide scholarly discussion. This paper argues that recent studies in experimental philosophy suggest that people are in fact “natural com- patibilists”. To support this claim, it surveys the experimental literature bearing directly (section 1) or indirectly (section 2) upon this issue, before pointing to three possible limitations of this claim (section 3). However, notwithstanding these limitations, the investigation concludes that the existing empirical evidence seems to support the view that most people have compatibilist intuitions. Key words: experimental philosophy; free will; moral responsibility; determin- ism Introduction The recently developed field of experimental philosophy advocates a methodolog- ical shift toward the use of an experimental methodology, in order to make progress on problems in philosophy (Knobe and Nichols, 2008). On a narrow view, experimen- tal philosophy is an experimental investigation of our intuitions about philosophical issues; on a larger view, it encompasses all tentative attempts to make progress on philosophical questions using experimental methods (Cova, 2012). Recently, a growing number of studies in experimental philosophy are addressing the relationship between free will and moral responsibility. Most of these aim (i) at testing whether people have the intuition that an agent in a deterministic universe cannot have free will and be morally responsible for his or her actions by (ii) probing their intuitions on small vignettes1. -

Experimental Philosophy and Feminist Epistemology: Conflicts and Complements

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2018 Experimental Philosophy and Feminist Epistemology: Conflicts and Complements Amanda Huminski The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2826 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] EXPERIMENTAL PHILOSOPHY AND FEMINIST EPISTEMOLOGY: CONFLICTS AND COMPLEMENTS by AMANDA HUMINSKI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Philosophy in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 © 2018 AMANDA HUMINSKI All Rights Reserved ii Experimental Philosophy and Feminist Epistemology: Conflicts and Complements By Amanda Huminski This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Philosophy in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________ ________________________________________________ Date Linda Martín Alcoff Chair of Examining Committee _______________________________ ________________________________________________ Date Nickolas Pappas Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Jesse Prinz Miranda Fricker THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Experimental Philosophy and Feminist Epistemology: Conflicts and Complements by Amanda Huminski Advisor: Jesse Prinz The recent turn toward experimental philosophy, particularly in ethics and epistemology, might appear to be supported by feminist epistemology, insofar as experimental philosophy signifies a break from the tradition of primarily white, middle-class men attempting to draw universal claims from within the limits of their own experience and research. -

Experimental Philosophy and Free Will Tamler Sommers* University of Houston

Philosophy Compass 5/2 (2010): 199–212, 10.1111/j.1747-9991.2009.00273.x Experimental Philosophy and Free Will Tamler Sommers* University of Houston Abstract This paper develops a sympathetic critique of recent experimental work on free will and moral responsibility. Section 1 offers a brief defense of the relevance of experimental philosophy to the free will debate. Section 2 reviews a series of articles in the experimental literature that probe intuitions about the ‘‘compatibility question’’—whether we can be free and morally responsible if determinism is true. Section 3 argues that these studies have produced valuable insights on the fac- tors that influence our judgments on the compatibility question, but that their general approach suffers from significant practical and philosophical difficulties. Section 4 reviews experimental work addressing other aspects of the free will ⁄ moral responsibility debate, and section 5 concludes with a discussion of avenues for further research. 1. Introduction The precise meaning of ‘experimental philosophy’ is a matter of controversy even among its practitioners, but all agree that it refers to a movement which employs the methods of empirical science to shed light on philosophical debates. Most commonly, experimental philosophers attempt to probe ordinary intuitions about a particular case or question in hopes of learning about the psychological processes that underlie these intuitions (Knobe 2007).1 The unifying conviction behind the movement is that many deep philosophical problems ‘can only be properly addressed by immersing oneself in the messy, contingent, highly variable truths about how human beings really are’.2 And the problem that has received the most attention from experimental philosophers thus far is the problem of free will. -

Editorial: Psychology and Experimental Philosophy

Rev.Phil.Psych. (2010) 1:157–160 DOI 10.1007/s13164-009-0012-5 Editorial: Psychology and Experimental Philosophy Joshua Knobe & Tania Lombrozo & Edouard Machery Published online: 1 December 2009 # Springer Science + Business Media B.V. 2009 Recent years have seen an explosion of new work at the intersection of philosophy and experimental psychology. This work takes the concerns with moral and conceptual issues that have so long been associated with philosophy and connects them with the use of systematic and well-controlled empirical investigations that one more typically finds in psychology. Work in this new field often goes under the name “experimental philosophy”. The aim of the present volume is to bring together some important new papers that demonstrate the promise and potential of this emerging field. The work collected here spans a wide range of philosophical topics—from ethics to epistemology to the philosophy of mind—and examines the ways in which empirical data can inform research in all of these fields. In addition, we have included a number of papers that offer critiques of contemporary experimental philosophy, suggesting ways in which existing studies might fail to address the philosophical questions they are supposed to be helping us to resolve. Geoffrey Goodwin and John Darley present a series of experimental studies investigating people’s ordinary intuitions in metaethics. Their research provides some tantalizing initial evidence that moral relativism is associated with a kind of “open” attitude toward ethical issues while a belief in objective moral truths is associated with a more “closed” attitude. Strikingly, the Goodwin and Darley studies show that relativism is more common among subjects who are high in an ability to J. -

Two Origin Stories for Experimental Philosophy

teorema Vol. XXXVI/3, 2017, pp. 23-43 ISSN: 0210-1602 [BIBLID 0210-1602 (2017) 36:3; pp. 23-43] Two Origin Stories for Experimental Philosophy Justin Sytsma RESUMEN Tanto los defensores como los críticos de la filosofía experimental la describen a menudo en términos estrictos como el estudio empírico de las intuiciones de la gente sobre asuntos filosóficos. Esta concepción se corresponde con una historia de este campo de origen estrecho; creció a partir de una insatisfacción con el uso acrítico de las propias in- tuiciones de los filósofos usadas como evidencia para sus aserciones. En contraste con esta situación, un número creciente de filósofos experimentales ha adoptado explícita- mente una concepción amplia de esta sub-disciplina, que la considera simplemente como el uso de métodos empíricos para el tratamiento de problemas filosóficos. Y esta concepción tiene correspondientemente una historia de origen amplio; el campo creció a partir del reconocimiento de que los filósofos hacen a menudo afirmaciones empíricas y de que estas exigen un apoyo empírico. En este artículo, argumento a favor de que la concepción amplia debería aceptarse y ofrezo apoyo para la historia con este origen. PALABRAS CLAVE: filosofía experimental, concepción amplia, concepción estrecha, intuiciones, naturalismo. ABSTRACT Both advocates and critics of experimental philosophy often describe it in narrow terms as being the empirical study of people’s intuitions about philosophical cases. This conception corresponds with a narrow origin story for the field — it grew out of a dissat- isfaction with the uncritical use of philosophers’ own intuitions as evidence for philo- sophical claims. In contrast, a growing number of experimental philosophers have explicitly embraced a broad conception of the sub-discipline, which treats it as simply the use of empirical methods to inform philosophical problems. -

Experimental Philosophy

Forthcoming in Annual Review of Psychology Experimental Philosophy Joshua Knobe 1,2 , Wesley Buckwalter 3, Shaun Nichols 4, Philip Robbins 5, Hagop Sarkissian 6, and Tamler Sommers 7 1 Program in Cognitive Science, Yale University; 2 Department of Philosophy, Yale University; 3 Department of Philosophy, City University of New York, Graduate Center; 4 Department of Philosophy, University of Arizona; 5 Department of Philosophy, University of Missouri; 6 Department of Philosophy, City University of New York, Baruch College; 7 Department of Philosophy, University of Houston. Abstract Experimental philosophy is a new interdisciplinary field that uses methods normally associated with psychology to investigate questions normally associated with philosophy. The present review focuses on research in experimental philosophy on four central questions. First, why is it that people’s moral judgments appear to influence their intuitions about seemingly nonmoral questions? Second, do people think that moral questions have objective answers, or do they see morality as fundamentally relative? Third, do people believe in free will, and do they see free will as compatible with determinism? Fourth, how do people determine whether an entity is conscious? Keywords: moral psychology, moral relativism, free will, consciousness, causation. INTRODUCTION Contemporary work in philosophy is shot through with appeals to intuition. When a philosopher wants to understand the nature of knowledge or causation or free will, the usual approach is to begin by constructing a series of imaginary cases designed to elicit prereflective judgments about the nature of these phenomena. These prereflective judgments are then treated as important sources of evidence. This basic approach has been applied with great sophistication across a wide variety of different domains. -

David Hume Has Been Largely Read As a Philosopher but Not As a Scientist

THE VERA CAUSA PRINCIPLE IN 18 TH CENTURY MORAL PSYCHOLOGY 1 FERNANDO MORETT David Hume has been largely read as a philosopher but not as a scientist. In this article I discuss his work exclusively as a case of science; in particular as a case of early modern science. I compare the moral psychology of self-interest, sympathy and sentiments of humanity he argues for with the moral psychology of universal self-interest from Bernard Mandeville, presenting the controversy between the two as a case of theory choice. David Hume, Adam Smith and Francis Hutcheson regarded the psychology of self-interest advanced by Thomas Hobbes and Bernard Mandeville as the rival theory to be defeated; it was a theory making ‘so much noise in the world’, Smith reports 2. Hume positively praises Mandeville’s theory in the first pages of the Treatise . This volume pays more attention to self-interest than An Enquiry Concerning the Principles of Morals, in which Hume discusses the disinterested passions of humanity and benevolence in more detail. Both Hume and Smith were highly critical of Mandeville’s theory, which they considered to be ‘malignant’ and ‘wholly pernicious’ because it leaves no grounds for ‘feelings sympathy and humanity’. They actually allude to Mandeville with epithets such as ‘sportive sceptic’ and ‘superficial reasoner’, whose reasoning is ‘ingenious sophistry’. 3 Hume strongly criticises the self-interested individuals described by Mandeville who are ‘monsters’ ‘unconcerned, either for the public good of a community or the private utility of others’ 4; they are replicas of Ebenezer Scrooge who even at Christmas shows no humanity, no concern for others. -

RETHINKING EMPIRICISM and MATERIALISM:THE REVISIONIST VIEW Charles Wolfe

RETHINKING EMPIRICISM AND MATERIALISM:THE REVISIONIST VIEW Charles Wolfe To cite this version: Charles Wolfe. RETHINKING EMPIRICISM AND MATERIALISM:THE REVISIONIST VIEW. Annales Philosophici, Philosophy Dept., University of Oradea, 2010, 1, pp.101-113. hal-01238130 HAL Id: hal-01238130 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01238130 Submitted on 4 Dec 2015 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. ANNALES PHILOSOPHICI, Issue 1/2010 RETHINKING EMPIRICISM AND MATERIALISM:THE REVISIONIST VIEW Charles T. Wolfe Unit for History and Philosophy of Science University of Sydney [email protected] Abstract. There is an enduring story about empiricism, which runs as follows: from Locke onwards to Carnap, empiricism is the doctrine in which raw sense-data are received through the passive mechanism of perception; experience is the effect produced by external reality on the mind or ‘receptors’. Empiricism on this view is the ‘handmaiden’ of experimental natural science, seeking to redefine philosophy and its methods in conformity with the results of modern science. Secondly, there is a story about materialism, popularized initially by Marx and Engels and later restated as standard, ‘textbook’ history of philosophy in the English-speaking world. -

DAVID HUME the Essential DAVID HUME James R

The Essential DAVID HUME The Essential DAVID HUME DAVID The Essential James R. Otteson by James R. Otteson Fraser Institute d www.fraserinstitute.org The Essential David Hume by James R. Otteson Fraser Institute www.fraserinstitute.org 2021 Copyright © 2021 by the Fraser Institute. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. The author of this publication has worked independently and opinions expressed by him are, therefore, his own, and do not necessarily reflect the opinions of the Fraser Institute or its supporters, directors, or staff. This publication in no way implies that the Fraser Institute, its directors, or staff are in favour of, or oppose the passage of, any bill; or that they support or oppose any particular political party or candidate. Printed and bound in Canada Cover design and artwork Bill C. Ray ISBN 978-0-88975-626-7 Contents Preface, Acknowledgments, and Note on Texts Used / vii 1 Who was David Hume? / 1 2 Empiricism / 7 3 Justice, Conflict, and Scarcity / 17 4 The Origins of Government and the Social Contract / 27 5 Commercial Society / 41 6 Trade, Money, and Debt / 49 7 Virtue, Religion, and the End of Life / 61 8 Happiness, Friendship, and Tragedy / 69 Further Reading / 77 Publishing information / 81 About the author / 82 Publisher’s acknowledgments / 82 Supporting the Fraser Institute / 83 Purpose, funding, and independence / 83 About the Fraser Institute / 84 Editorial Advisory Board / 85 To Max Hocutt Teacher, mentor, great-souled friend Fraser Institute d www.fraserinstitute.org Preface, Acknowledgments, and Note on Texts Used Preface and Acknowledgments This book is part of the Fraser Institute’s Essential Scholars series, each volume of which is intended to present the ten (or so) main things everyone should know about a major figure in the history of both economics and moral philos- ophy.