Experimental Philosophy and Free Will Tamler Sommers* University of Houston

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Western Philosophy Rev

Designed by John Cornet, Phoenix HS (Ore) Western Philosophy rev. September 2012 The very process of philosophy has been a driving force in the tranformation of the world. From the figure who dwells upon how to achieve power, to the minister who contemplates the paradox of the only truth (their faith) yet which is also stagnent, to the astronomers who are searching the stars for signs of other civilizations, to the revolutionaries who sought to construct a national government which would protect the rights of the minority, the very exercise of philosophy and philosophical thought is at a core of human nature. Philosophy addresses what are sometimes called the "big questions." These include questions of morality and ethics, ideology/faith,, politics, the truth of knowledge, the nature of reality, and the meaning of human existance (...just to name a few!) (Religion addresses some of the same questions, but while philosophy and religion overlap in some questions, they can and do differ significantly in the approach they take to answering them.) Subject Learning Outcomes Skills-Based Learning Outcomes Behavioral Expectations and Grading Policy Develop an appreciation for and enjoyment of Organize, maintain and learn how to study from a learning, particularly in how learning should subject-specific notebook Attendance, participation and cause us to question what we think we know Be able to demonstrate how to take notes (including being prepared are daily and have a willingness to entertain new utilizing two-column format) expectations perspectives on issues. Be able to engage in meaningful, substantive discussion A classroom culture of respect and Students will develop familiarity with major with others. -

1 Forthcoming in Oxford Studies in Experimental Philosophy Causal Reasoning

Forthcoming in Oxford Studies in Experimental Philosophy Causal Reasoning: Philosophy and Experiment* James Woodward History and Philosophy of Science University of Pittsburgh 1. Introduction The past few decades have seen much interesting work, both within and outside philosophy, on causation and allied issues. Some of the philosophy is understood by its practitioners as metaphysics—it asks such questions as what causation “is”, whether there can be causation by absences, and so on. Other work reflects the interests of philosophers in the role that causation and causal reasoning play in science. Still other work, more computational in nature, focuses on problems of causal inference and learning, typically with substantial use of such formal apparatuses as Bayes nets (e.g. , Pearl, 2000, Spirtes et al, 2001) or hierarchical Bayesian models (e.g. Griffiths and Tenenbaum, 2009). All this work – the philosophical and the computational -- might be described as “theoretical” and it often has a strong “normative” component in the sense that it attempts to describe how we ought to learn, reason, and judge about causal relationships. Alongside this normative/theoretical work, there has also been a great deal of empirical work (hereafter Empirical Research on Causation or ERC) which focuses on how various subjects learn causal relationships, reason and judge causally. Much of this work has been carried out by psychologists, but it also includes contributions by primatologists, researchers in animal learning, and neurobiologists, and more rarely, philosophers. In my view, the interactions between these two groups—the normative/theoretical and the empirical -- has been extremely fruitful. In what follows, I describe some ideas about causal reasoning that have emerged from this research, focusing on the “interventionist” ideas that have figured in my own work. -

Author's Proof

8-88.1-2 Tognazzini FNL 5/22/12 11:35 AM Page 73 (Black plate) AUTHOR’S PROOF 1 UNDERSTANDING SOURCE 2 INCOMPATIBILISM 3 4 Neal A. Tognazzini 5 6 7 8 Abstract: Source incompatibilism is an increasingly popular version 9 of incompatibilism about determinism and moral responsibility. 10 However, many self-described source incompatibilists formulate the 11 thesis differently, resulting in conceptual confusion that can obscure 12 the relationship between source incompatibilism and other views in 13 the neighborhood. In this paper I canvas various formulations of the 14 thesis in the literature and argue in favor of one as the least likely to 15 lead to conceptual confusion. It turns out that accepting my formula- 16 tion has some surprising (but helpful) taxonomical consequences. 17 18 19 Recently, many incompatibilists about determinism and moral responsibility 20 have begun calling themselves ‘source incompatibilists,’ mostly to distinguish themselves from those incompatibilists who focus exclusively on whether 21 determinism rules out the infamous ability to do otherwise. But while those 22 who call themselves ‘source incompatibilists’ are united in the desire to distin- 23 guish themselves from the more traditional sort of incompatibilist, their thesis 24 cannot be understood merely in terms of what it is . To understand source 25 not incompatibilism fully, the thesis needs some positive content. And it is in the 26 attempt to formulate positive content where theorists divide. As a result, when 27 someone claims to be a source incompatibilist, one always has to ask the fol- 28 low-up question: “What do you mean by ‘source incompatibilism’?” before one 29 can understand the claim. -

Experimental Philosophy, Robert Kane, and the Concept of Free Will

Journal of Cognition and Neuroethics Experimental Philosophy, Robert Kane, and the Concept of Free Will J. Neil Otte University at Buffalo, The State University of New York Biography J. Neil Otte is presently in the Ph.D. program at the University at Buffalo (SUNY) and works in moral psychology, cognitive science, and the history of philosophy. For six years, he was an adjunct lecturer in philosophy at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City. In the last three years, he has been an organizer of the Buffalo Annual Experimental Philosophy Conference, an organizer for a conference on sentiment and reason in early modern philosophy, and has worked as an ontologist for the research foundation, CUBRC. Acknowledgements The author wishes to thank Gunnar Björnsson, Gregg Caruso, and Oisín Deery for their supportive comments and conversation during the Free Will Conference at the Insight Institute of Neurosurgery and Neuroscience in Fall of 2014, as well as conference organizer Jami Anderson. Publication Details Journal of Cognition and Neuroethics (ISSN: 2166-5087). March, 2015. Volume 3, Issue 1. Citation Otte, J. Neil. 2015. “Experimental Philosophy, Robert Kane, and the Concept of Free Will.” Journal of Cognition and Neuroethics 3 (1): 281–296. Experimental Philosophy, Robert Kane, and the Concept of Free Will J. Neil Otte Abstract Trends in experimental philosophy have provided new and compelling results that are cause for re-evaluations in contemporary discussions of free will. In this paper, I argue for one such re-evaluation by criticizing Robert Kane’s well-known views on free will. I argue that Kane’s claims about pre-theoretical intuitions are not supported by empirical findings on two accounts. -

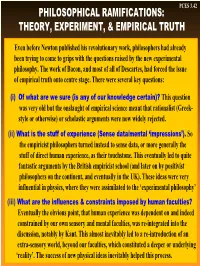

Philosophical Ramifications: Theory, Experiment, & Empirical Truth

PCES 3.42 PHILOSOPHICAL RAMIFICATIONS: THEORY, EXPERIMENT, & EMPIRICAL TRUTH Even before Newton published his revolutionary work, philosophers had already been trying to come to grips with the questions raised by the new experimental philosophy. The work of Bacon, and most of all of Descartes, had forced the issue of empirical truth onto centre stage. There were several key questions: (i) Of what are we sure (is any of our knowledge certain)? This question was very old but the onslaught of empirical science meant that rationalist (Greek- style or otherwise) or scholastic arguments were now widely rejected. (ii) What is the stuff of experience (Sense data/mental ‘impressions’). So the empiricist philosophers turned instead to sense data, or more generally the stuff of direct human experience, as their touchstone. This eventually led to quite fantastic arguments by the British empiricist school (and later on by positivist philosophers on the continent, and eventually in the UK). These ideas were very influential in physics, where they were assimilated to the ‘experimental philosophy’ (iii) What are the influences & constraints imposed by human faculties? Eventually the obvious point, that human experience was dependent on and indeed constrained by our own sensory and mental faculties, was re-integrated into the discussion, notably by Kant. This almost inevitably led to a re-introduction of an extra-sensory world, beyond our faculties, which constituted a deeper or underlying ‘reality’. The success of new physical ideas inevitably helped this process. PCES 3.43 BRITISH EMPIRICISM I: Locke & “Sensations” Locke was the first British philosopher of note after Bacon; his work is a reaction to the European rationalists, and continues to elaborate ‘experimental philosophy’. -

Life with Augustine

Life with Augustine ...a course in his spirit and guidance for daily living By Edmond A. Maher ii Life with Augustine © 2002 Augustinian Press Australia Sydney, Australia. Acknowledgements: The author wishes to acknowledge and thank the following people: ► the Augustinian Province of Our Mother of Good Counsel, Australia, for support- ing this project, with special mention of Pat Fahey osa, Kevin Burman osa, Pat Codd osa and Peter Jones osa ► Laurence Mooney osa for assistance in editing ► Michael Morahan osa for formatting this 2nd Edition ► John Coles, Peter Gagan, Dr. Frank McGrath fms (Brisbane CEO), Benet Fonck ofm, Peter Keogh sfo for sharing their vast experience in adult education ► John Rotelle osa, for granting us permission to use his English translation of Tarcisius van Bavel’s work Augustine (full bibliography within) and for his scholarly advice Megan Atkins for her formatting suggestions in the 1st Edition, that have carried over into this the 2nd ► those generous people who have completed the 1st Edition and suggested valuable improvements, especially Kath Neehouse and friends at Villanova College, Brisbane Foreword 1 Dear Participant Saint Augustine of Hippo is a figure in our history who has appealed to the curiosity and imagination of many generations. He is well known for being both sinner and saint, for being a bishop yet also a fellow pilgrim on the journey to God. One of the most popular and attractive persons across many centuries, his influence on the church has continued to our current day. He is also renowned for his influ- ence in philosophy and psychology and even (in an indirect way) art, music and architecture. -

METAPHYSICS and the WORLD CRISIS Victor B

METAPHYSICS AND THE WORLD CRISIS Victor B. Brezik, CSB (The Basilian Teacher, Vol. VI, No. 2, November, 1961) Several years ago on one of his visits to Toronto, M. Jacques Maritain, when he was informed that I was teaching a course in Metaphysics, turned to me and inquired with an obvious mixture of humor and irony indicated by a twinkle in the eyes: “Are there some students here interested in Metaphysics?” The implication was that he himself was finding fewer and fewer university students with such an interest. The full import of M. Maritain’s question did not dawn upon me until later. In fact, only recently did I examine it in a wider context and realize its bearing upon the present world situation. By a series of causes ranging from Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason in the 18th century and the rise of Positive Science in the 19th century, to the influence of Pragmatism, Logical Positivism and an absorbing preoccupation with technology in the 20th century, devotion to metaphysical studies has steadily waned in our universities. The fact that today so few voices are raised to deplore this trend is indicative of the desuetude into which Metaphysics has fallen. Indeed, a new school of philosophers, having come to regard the study of being as an entirely barren field, has chosen to concern itself with an analysis of the meaning of language. (Volume XXXIV of Proceedings of the American Catholic Philosophical Association deals with Analytical Philosophy.) Yet, paradoxically, while an increasing number of scholars seem to be losing serious interest in metaphysical studies, the world crisis we are experiencing today appears to be basically a crisis in Metaphysics. -

Introduction to Philosophy KRSN PHL1010 Institution Course ID

Introduction to Philosophy KRSN PHL1010 Institution Course ID Course Title Credit Hours Allen County CC HUM 125 Philosophy 3 Barton County CC Phil 1602 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Butler CC PL 290 Philosophy 1 3 Cloud County CC PH 100 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Coffeyville CC HUMN 104 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Colby CC Pl 101 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Cowley County CC PHO 6447 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Dodge City CC PHIL 201 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Fort Scott CC PH 1113 Philosophy of Life 3 Garden City CC PHIL 101 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Highland CC PHI 101 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Hutchinson CC PL 101 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Independence CC SOC2003 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Johnson County CC PHIL 121 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Kansas City KCC PHIL 0103 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Labette CC PHIL 101 Philosophy 1 3 Neosho County CC HUM 103 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Pratt CC PHL 130 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Seward County CC PH 2203 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Flint Hills TC Not Offered Not Offered Manhattan Area TC Not Offered Not Offered North Central KTC Not Offered Not Offered Northwest KTC Not Offered Not Offered Salina Area TC Not Offered Not Offered Wichita Area TC Not Offered Not Offered Emporia St. U. PI 225 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Fort Hays St. U. PHIL 120 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Kansas St. U. PHILO 100 Introduction to Philosophical Problems 3 Pittsburg St. U. PHIL 103 Introduction to Philosophy 3 U. Of Kansas PHIL 140 Introduction to Philosophy 3 Wichita St. -

Can Libertarianism Or Compatibilism Capture Aquinas' View on the Will? Kelly Gallagher University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville ScholarWorks@UARK Theses and Dissertations 8-2014 Can Libertarianism or Compatibilism Capture Aquinas' View on the Will? Kelly Gallagher University of Arkansas, Fayetteville Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd Part of the Comparative Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Gallagher, Kelly, "Can Libertarianism or Compatibilism Capture Aquinas' View on the Will?" (2014). Theses and Dissertations. 2229. http://scholarworks.uark.edu/etd/2229 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Can Libertarianism or Compatibilism Capture Aquinas’ View on the Will? Can Libertarianism or Compatibilism Capture Aquinas’ View on the Will? A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Philosophy by Kelly Gallagher Benedictine College Bachelor of Arts in Philosophy, 2010 Benedictine College Bachelor of Arts in Theology, 2010 August 2014 University of Arkansas This thesis is approved for recommendation to the Graduate Council. Dr. Thomas Senor Thesis Director Dr. Lynne Spellman Dr. Eric Funkhouser Committee Member Committee Member Abstract The contemporary free will debate is largely split into two camps, libertarianism and compatibilism. It is commonly assumed that if one is to affirm the existence of free will then she will find herself in one of these respective camps. Although merits can be found in each respective position, I find that neither account sufficiently for free will. This thesis, therefore, puts the view of Thomas Aquinas in dialogue with the contemporary debate and argues that his view cannot be captured by either libertarianism or compatibilism and that his view offers a promising alternative view that garners some of the strengths from both contemporary positions without taking on their respective shortcomings. -

Agency: Moral Identity and Free Will

D Agency AVID Moral Identity and Free Will W DAVID WEISSMAN EISSMAN There is agency in all we do: thinking, doing, or making. We invent a tune, play, or use it to celebrate an occasion. Or we make a conceptual leap and ask more ab- stract ques� ons about the condi� ons for agency. They include autonomy and self- appraisal, each contested by arguments immersing us in circumstances we don’t control. But can it be true we that have no personal responsibility for all we think Agency and do? Agency: Moral Ident ty and Free Will proposes that delibera� on, choice, and free will emerged within the evolu� onary history of animals with a physical advantage: Moral Identity organisms having cell walls or exoskeletons had an internal space within which to protect themselves from external threats or encounters. This defense was both and Free Will structural and ac� ve: such organisms could ignore intrusions or inhibit risky behav- ior. Their capaci� es evolved with � me: inhibi� on became the power to deliberate and choose the manner of one’s responses. Hence the ability of humans and some other animals to determine their reac� ons to problema� c situa� ons or to informa- � on that alters values and choices. This is free will as a material power, not as the DAVID WEISSMAN conclusion to a conceptual argument. Having it makes us morally responsible for much we do. It prefi gures moral iden� ty. A GENCY Closely argued but plainly wri� en, Agency: Moral Ident ty and Free Will speaks for autonomy and responsibility when both are eclipsed by ideas that embed us in his- tory or tradi� on. -

Experimental Philosophy Jordan Kiper, Stephen Stich, H. Clark Barrett

Experimental Philosophy Jordan Kiper, Stephen Stich, H. Clark Barrett, & Edouard Machery Kiper, J., Stich, S., Barrett, H.C., & Machery, E. (in press). Experimental philosophy. In D. Ludwig, I. Koskinen, Z. Mncube, L. Poliseli, & L. Reyes-Garcia (Eds.), Global Epistemologies and Philosophies of Science. New York, NY: Routledge. Acknowledgments: This publication was made possible through the support of a grant from the John Templeton Foundation. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the John Templeton Foundation. Abstract Philosophers have argued that some philosophical concepts are universal, but it is increasingly clear that the question of philosophical universals is far from settled, and that far more cross- cultural research is necessary. In this chapter, we illustrate the relevance of investigating philosophical concepts and describe results from recent cross-cultural studies in experimental philosophy. We focus on the concept of knowledge and outline an ongoing project, the Geography of Philosophy Project, which empirically investigates the concepts of knowledge, understanding, and wisdom across cultures, languages, religions, and socioeconomic groups. We outline questions for future research on philosophical concepts across cultures, with an aim towards resolving questions about universals and variation in philosophical concepts. 1 Introduction For centuries, thinkers have urged that fundamental philosophical concepts, such as the concepts of knowledge or right and wrong, are universal or at least shared by all rational people (e.g., Plato 1892/375 BCE; Kant, 1998/1781; Foot, 2003). Yet many social scientists, in particular cultural anthropologists (e.g., Boas, 1940), but also continental philosophers such as Foucault (1969) have remained skeptical of these claims. -

The Thought of St. Augustine Churchman 104/4 1990

The Thought of St. Augustine Churchman 104/4 1990 Rod Garner St. Augustine, also known as Aurelius Augustinus, was born in AD 354 and died in 430 at Hippo, North Africa, in a region now better known as modern Algeria. He was raised in a town called Thagaste. There he suffered the twin misfortunes of the early death of his father, Patrick, and an impoverished education which did little to foster his knowledge and understanding. His mother, Monica, influenced him deeply and remained his best friend until her death in 388. Three years later (and against his wishes) Augustine was ordained presbyter for a small congregation at the busy seaport of Hippo Regius, forty five miles from his birthplace. His reluctance could not mask his outstanding abilities and it was not long before he was consecrated bishop of the province. For thirty four years his episcopal duties engaged him in a constant round of preaching, administration, travel and the care of his people. Despite the demands on his time, and the various controversies which embroiled him as a champion of orthodoxy, he never ceased to be a thinker and scholar. He wrote extensively and his surviving writings exceed those of any other ancient author. His vast output includes one hundred and thirteen books and treatises, over two hundred letters, and more than five hundred sermons. Although a citizen of the ancient world whose outlook was shaped by the cultures of Greece and Rome, Augustine is in important respects our contemporary. His influence has proved pervasive, affecting the way we think about the human condition and the meaning of the word ‘God’.