Experimental Philosophy Jordan Kiper, Stephen Stich, H. Clark Barrett

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Forthcoming in Oxford Studies in Experimental Philosophy Causal Reasoning

Forthcoming in Oxford Studies in Experimental Philosophy Causal Reasoning: Philosophy and Experiment* James Woodward History and Philosophy of Science University of Pittsburgh 1. Introduction The past few decades have seen much interesting work, both within and outside philosophy, on causation and allied issues. Some of the philosophy is understood by its practitioners as metaphysics—it asks such questions as what causation “is”, whether there can be causation by absences, and so on. Other work reflects the interests of philosophers in the role that causation and causal reasoning play in science. Still other work, more computational in nature, focuses on problems of causal inference and learning, typically with substantial use of such formal apparatuses as Bayes nets (e.g. , Pearl, 2000, Spirtes et al, 2001) or hierarchical Bayesian models (e.g. Griffiths and Tenenbaum, 2009). All this work – the philosophical and the computational -- might be described as “theoretical” and it often has a strong “normative” component in the sense that it attempts to describe how we ought to learn, reason, and judge about causal relationships. Alongside this normative/theoretical work, there has also been a great deal of empirical work (hereafter Empirical Research on Causation or ERC) which focuses on how various subjects learn causal relationships, reason and judge causally. Much of this work has been carried out by psychologists, but it also includes contributions by primatologists, researchers in animal learning, and neurobiologists, and more rarely, philosophers. In my view, the interactions between these two groups—the normative/theoretical and the empirical -- has been extremely fruitful. In what follows, I describe some ideas about causal reasoning that have emerged from this research, focusing on the “interventionist” ideas that have figured in my own work. -

Experimental Philosophy, Robert Kane, and the Concept of Free Will

Journal of Cognition and Neuroethics Experimental Philosophy, Robert Kane, and the Concept of Free Will J. Neil Otte University at Buffalo, The State University of New York Biography J. Neil Otte is presently in the Ph.D. program at the University at Buffalo (SUNY) and works in moral psychology, cognitive science, and the history of philosophy. For six years, he was an adjunct lecturer in philosophy at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City. In the last three years, he has been an organizer of the Buffalo Annual Experimental Philosophy Conference, an organizer for a conference on sentiment and reason in early modern philosophy, and has worked as an ontologist for the research foundation, CUBRC. Acknowledgements The author wishes to thank Gunnar Björnsson, Gregg Caruso, and Oisín Deery for their supportive comments and conversation during the Free Will Conference at the Insight Institute of Neurosurgery and Neuroscience in Fall of 2014, as well as conference organizer Jami Anderson. Publication Details Journal of Cognition and Neuroethics (ISSN: 2166-5087). March, 2015. Volume 3, Issue 1. Citation Otte, J. Neil. 2015. “Experimental Philosophy, Robert Kane, and the Concept of Free Will.” Journal of Cognition and Neuroethics 3 (1): 281–296. Experimental Philosophy, Robert Kane, and the Concept of Free Will J. Neil Otte Abstract Trends in experimental philosophy have provided new and compelling results that are cause for re-evaluations in contemporary discussions of free will. In this paper, I argue for one such re-evaluation by criticizing Robert Kane’s well-known views on free will. I argue that Kane’s claims about pre-theoretical intuitions are not supported by empirical findings on two accounts. -

Curriculum Vitae 04/04/2021

Curriculum Vitae 04/04/2021 PETER CARRUTHERS [email protected] http://faculty.philosophy.umd.edu/pcarruthers/ 7400 Glenside Drive Department of Philosophy Takoma Park University of Maryland MD 20912-6923 College Park, MD 20742 Tel.: 301 270 5107 Tel.: 301 405 5705 EMPLOYMENT HISTORY 2001-present UNIVERSITY OF MARYLAND, COLLEGE PARK. Professor (2001–2018), Department of Philosophy; Distinguished University Professor (2018–present). Chair of Department (June 2001–December 2008). Associate Member, Neuroscience and Cognitive Science Program (NACS) (2002–present). Member, Brain and Behavior Initiative (BBI) (2016–present). 1991-2001 UNIVERSITY OF SHEFFIELD. Senior Lecturer (1991-2), Department of Philosophy; Professor (1992-2001). Head of Department (1993-8). Director, Hang Seng Centre for Cognitive Studies (1992-2000). 1985-91 UNIVERSITY OF ESSEX. Lecturer (tenured) (1985-9), Department of Philosophy; Senior Lecturer (1989-91). 1989-90 — UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN, ANN ARBOR. Visiting Associate Professor, Department of Philosophy. 1981-85 QUEEN’S UNIVERSITY OF BELFAST. Lecturer, Department of Philosophy (confirmed in post 1984). 1979-81 UNIVERSITY OF ST. ANDREWS. Temporary Lecturer, Department of Logic and Metaphysics. 1978-79 UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD, LADY MARGARET HALL. Temporary Lecturer (part-time: 6 hours tutoring per week). EDUCATION AND QUALIFICATIONS 1977-79 UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD, BALLIOL COLLEGE. D.Phil. in Philosophy (1980). Thesis: “The place of the private language argument in the philosophy of language.” (Supervisor: Michael Dummett. Examiners: Elizabeth Anscombe, Christopher Peacocke.) 1971-77 UNIVERSITY OF LEEDS. M.Phil. in Philosophy (1977). Thesis: “Blame: an analysis.” (Supervisor: Jennifer Jackson.) Papers: Wittgenstein, Philosophical Logic, Political Philosophy. B.A. (Honors) in Philosophy (1975). 1st Class. “Congratulatory 1st.” Carruthers CV 2 HONORS AND AWARDS 2020: Graduate Faculty Mentor of the Year Award (one of 10 awards made annually among faculty at the University of Maryland). -

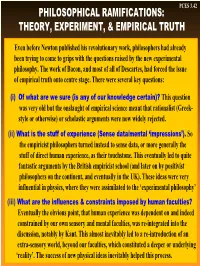

Philosophical Ramifications: Theory, Experiment, & Empirical Truth

PCES 3.42 PHILOSOPHICAL RAMIFICATIONS: THEORY, EXPERIMENT, & EMPIRICAL TRUTH Even before Newton published his revolutionary work, philosophers had already been trying to come to grips with the questions raised by the new experimental philosophy. The work of Bacon, and most of all of Descartes, had forced the issue of empirical truth onto centre stage. There were several key questions: (i) Of what are we sure (is any of our knowledge certain)? This question was very old but the onslaught of empirical science meant that rationalist (Greek- style or otherwise) or scholastic arguments were now widely rejected. (ii) What is the stuff of experience (Sense data/mental ‘impressions’). So the empiricist philosophers turned instead to sense data, or more generally the stuff of direct human experience, as their touchstone. This eventually led to quite fantastic arguments by the British empiricist school (and later on by positivist philosophers on the continent, and eventually in the UK). These ideas were very influential in physics, where they were assimilated to the ‘experimental philosophy’ (iii) What are the influences & constraints imposed by human faculties? Eventually the obvious point, that human experience was dependent on and indeed constrained by our own sensory and mental faculties, was re-integrated into the discussion, notably by Kant. This almost inevitably led to a re-introduction of an extra-sensory world, beyond our faculties, which constituted a deeper or underlying ‘reality’. The success of new physical ideas inevitably helped this process. PCES 3.43 BRITISH EMPIRICISM I: Locke & “Sensations” Locke was the first British philosopher of note after Bacon; his work is a reaction to the European rationalists, and continues to elaborate ‘experimental philosophy’. -

A Cognitive Theory of Pretense

A revised and abbreviated version of this paper is forthcoming in Cognition. Archived at Website for the Rutgers University Research Group on Evolution and Higher Cognition. A Cognitive Theory of Pretense Shaun Nichols Department of Philosophy College of Charleston Charleston, SC 29424 [email protected] and Stephen Stich Department of Philosophy and Center for Cognitive Science Rutgers University New Brunswick, NJ 08901 [email protected] Contents 1. Introduction 2. Some Examples of Pretense 3. Some Features of Pretense 4. A Theory about the Cognitive Mechanisms Underlying Pretense 5. A Comparison with Other Theories 6. Conclusion Abstract Recent accounts of pretense have been underdescribed in a number of ways. In this paper, we present a much more explicit cognitive account of pretense. We begin by presenting a number of real examples of pretense in children and adults. These examples bring out several features of pretense that any adequate theory of pretense must accommodate, and we use these features to develop our theory of pretense. On our theory, pretense representations are contained in a separate workspace, a Possible World Box which is part of the basic architecture of the human mind. The representations in the Possible World Box can have the same content as beliefs. Indeed, we suggest that pretense representations are in the same representational "code" as beliefs and that the representations in the Possible World Box are processed by the same inference and UpDating mechanisms that operate over real beliefs. Our model also posits a Script Elaborator which is implicated in the embellishment that occurs in pretense. Finally, we claim that the behavior that is seen in pretend play is motivated not from a "pretend desire", but from a real desire to act in a way that fits the description being constructed in the Possible World Box. -

CVII: 2 (February 2000), Pp

TAMAR SZABÓ GENDLER July 2014 Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences · Yale University · P.O. Box 208365 · New Haven, CT 06520-8365 E-mail: [email protected] · Office telephone: 203.432.4444 ACADEMIC EMPLOYMENT 2006- Yale University Academic Vincent J. Scully Professor of Philosophy (F2012-present) Professor of Philosophy (F2006-F2012); Professor of Psychology (F2009-present); Professor of Humanities (S2007-present); Professor of Cognitive Science (F2006-present) Administrative Dean, Faculty of Arts and Sciences (Sum2014-present) Deputy Provost, Humanities and Initiatives (F2013-Sum2014) Chair, Department of Philosophy (Sum2010-Sum2013) Chair, Cognitive Science Program (F2006-Sum2010) 2003-2006 Cornell University Academic Associate Professor of Philosophy (with tenure) (F2003-S2006) Administrative Director of Graduate Studies, Department of Philosophy (F2004-S2006) Co-Director, Program in Cognitive Studies (F2004-S2006) 1997-2003 Syracuse University Academic Associate Professor of Philosophy (with tenure) (F2002-S2003) Assistant Professor of Philosophy (tenure-track) (F1999-S2002) Allen and Anita Sutton Distinguished Faculty Fellow (F1997-S1999) Administrative Director of Undergraduate Studies, Department of Philosophy (F2001-S2003) 1996-1997 Yale University Academic Lecturer (F1996-S1997) EDUCATION 1990-1996 Harvard University. PhD (Philosophy), August 1996. Dissertation title: ‘Imaginary Exceptions: On the Powers and Limits of Thought Experiment’ Advisors: Robert Nozick, Derek Parfit, Hilary Putnam 1989-1990 University of California -

Newsletter Template

Rutgers Philosophy Newsletter Spring 2009 Rutgers is once again ranked 2nd overall Philosophy Department in the US… Inside: Every two years, Blackwell Publishers releases its Philosophical The doctoral program Gourmet Report—a ranking of the fifty best Philosophy departments 4 continues to attract top in the English-speaking world, based on the reputation and graduate students. Meet the accomplishments of their faculty members. In the February 2009 current group and learn what edition, Rutgers was once again ranked 2nd overall in the United rd recent PhDs have done. States (after NYU) and 3 overall in the world (after NYU and Oxford). In the specialty rankings, Rutgers was voted the top department internationally for Philosophy of Language and The New York Times highlights Cognitive Science, and tied for #1 in Epistemology and Mind. 6 Rutgers’ undergraduate Rutgers was among the top four departments for Metaphysics. And Philosophy program. Rutgers was within the top ten for Philosophy of Science, Applied Ethics, Decision Theory and Early Modern Philosophy. The surveys reflect the outstanding strength our department has in core areas. A Letter from the Chair 8 See more of the rankings at www.philosophicalgourmet.com. Catching up with the Faculty: New Research by Rutgers Professors; Conferences, Talks and Upcoming Projects This past year has brought some selection. In April, Larry Temkin changes to the Rutgers faculty. hosted a two-day conference While Barry Loewer continued on human rights in honor of as Chair, Jeff King took over as James Griffin. On May 13th- Graduate Vice-Chair and 14thRutgers will be hosting its first Martin Lin as Undergraduate Foundations of Statistical Vice-Chair. -

1 Joshua Knobe Yale University Take a Few Courses in Cognitive Science

FREE WILL AND THE SCIENTIFIC VISION1 Joshua Knobe Yale University [Forthcoming in Edouard Machery and Elizabeth O’Neill (eds.), Current Controversies in Experimental Philosophy. RoutledGe.] Take a few courses in cognitive science, and you are likely to come across a certain kind of metaphor for the workinGs of the human mind. The metaphor Goes like this: Consider a piece of computer software. The software consists of a collection of states and processes. We can predict what the software will do by lookinG at the complex ways in which these states and processes interact. The human mind works in more or less the same way. It too is just a complex collection of states and processes, and we can predict what a human being will do by thinking about the complex ways in which these states and processes interact. One can imaGine someone sayinG: ‘I see all these states and processes, but aren’t you forgetting somethinG further – namely, the person herself?’ This question, however, is a foolish one. It is no more helpful than it would be to say: ‘I see all these states and processes, but where is the software itself?’ The software just is a collection of states and processes, and the human mind is the same sort of thinG. This metaphor does a Good job of capturinG the basic approach one finds throuGhout the sciences of the mind. We miGht say that it captures the scientific vision of how the human mind works. But one could also imaGine another, very different metaphor for the workinGs of the mind. -

Nietzsche's Naturalism As a Critique of Morality and Freedom

NIETZSCHE’S NATURALISM AS A CRITIQUE OF MORALITY AND FREEDOM A thesis submitted to Kent State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Nathan W. Radcliffe December, 2012 Thesis written by Nathan W. Radcliffe B.S., University of Akron, 1998 M.A., Kent State University, 2012 Approved by Gene Pendleton____________________________________, Advisor David Odell‐Scott___________________________________, Chair, Department of Philosophy Raymond Craig_____________________________________, Dean, College of Arts and Sciences ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS....................................................................................................................v INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................................... 1 CHAPTERS I. NIETZSCHE’S NATURALISM AND ITS INFLUENCES....................................................... 8 1.1 Nietzsche’s Speculative‐Methodological Naturalism............................................ 8 1.2 Nietzsche’s Opposition to Materialism ............................................................... 15 1.3 The German Materialist Influence on Nietzsche................................................. 19 1.4 The Influence of Lange on Nietzsche .................................................................. 22 1.5 Nietzsche’s Break with Kant and Its Aftermath................................................... 25 1.6 Influences on Nietzsche’s Fatalism (Schopenhauer and Spinoza) -

Experimental Philosophy and the Compatibility of Free Will and Determinism: a Survey

Annals of the Japan Association for Philosophy of Science Vol.22 (2014) 17~37 17 Experimental Philosophy and the Compatibility of Free Will and Determinism: A Survey Florian Cova∗ and Yasuko Kitano∗∗ Abstract The debate over whether free will and determinism are compatible is con- troversial, and produces wide scholarly discussion. This paper argues that recent studies in experimental philosophy suggest that people are in fact “natural com- patibilists”. To support this claim, it surveys the experimental literature bearing directly (section 1) or indirectly (section 2) upon this issue, before pointing to three possible limitations of this claim (section 3). However, notwithstanding these limitations, the investigation concludes that the existing empirical evidence seems to support the view that most people have compatibilist intuitions. Key words: experimental philosophy; free will; moral responsibility; determin- ism Introduction The recently developed field of experimental philosophy advocates a methodolog- ical shift toward the use of an experimental methodology, in order to make progress on problems in philosophy (Knobe and Nichols, 2008). On a narrow view, experimen- tal philosophy is an experimental investigation of our intuitions about philosophical issues; on a larger view, it encompasses all tentative attempts to make progress on philosophical questions using experimental methods (Cova, 2012). Recently, a growing number of studies in experimental philosophy are addressing the relationship between free will and moral responsibility. Most of these aim (i) at testing whether people have the intuition that an agent in a deterministic universe cannot have free will and be morally responsible for his or her actions by (ii) probing their intuitions on small vignettes1. -

Experimental Philosophy and Feminist Epistemology: Conflicts and Complements

City University of New York (CUNY) CUNY Academic Works All Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects Dissertations, Theses, and Capstone Projects 9-2018 Experimental Philosophy and Feminist Epistemology: Conflicts and Complements Amanda Huminski The Graduate Center, City University of New York How does access to this work benefit ou?y Let us know! More information about this work at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu/gc_etds/2826 Discover additional works at: https://academicworks.cuny.edu This work is made publicly available by the City University of New York (CUNY). Contact: [email protected] EXPERIMENTAL PHILOSOPHY AND FEMINIST EPISTEMOLOGY: CONFLICTS AND COMPLEMENTS by AMANDA HUMINSKI A dissertation submitted to the Graduate Faculty in Philosophy in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, The City University of New York 2018 © 2018 AMANDA HUMINSKI All Rights Reserved ii Experimental Philosophy and Feminist Epistemology: Conflicts and Complements By Amanda Huminski This manuscript has been read and accepted for the Graduate Faculty in Philosophy in satisfaction of the dissertation requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. _______________________________ ________________________________________________ Date Linda Martín Alcoff Chair of Examining Committee _______________________________ ________________________________________________ Date Nickolas Pappas Executive Officer Supervisory Committee: Jesse Prinz Miranda Fricker THE CITY UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK iii ABSTRACT Experimental Philosophy and Feminist Epistemology: Conflicts and Complements by Amanda Huminski Advisor: Jesse Prinz The recent turn toward experimental philosophy, particularly in ethics and epistemology, might appear to be supported by feminist epistemology, insofar as experimental philosophy signifies a break from the tradition of primarily white, middle-class men attempting to draw universal claims from within the limits of their own experience and research. -

Experimental Philosophy and Free Will Tamler Sommers* University of Houston

Philosophy Compass 5/2 (2010): 199–212, 10.1111/j.1747-9991.2009.00273.x Experimental Philosophy and Free Will Tamler Sommers* University of Houston Abstract This paper develops a sympathetic critique of recent experimental work on free will and moral responsibility. Section 1 offers a brief defense of the relevance of experimental philosophy to the free will debate. Section 2 reviews a series of articles in the experimental literature that probe intuitions about the ‘‘compatibility question’’—whether we can be free and morally responsible if determinism is true. Section 3 argues that these studies have produced valuable insights on the fac- tors that influence our judgments on the compatibility question, but that their general approach suffers from significant practical and philosophical difficulties. Section 4 reviews experimental work addressing other aspects of the free will ⁄ moral responsibility debate, and section 5 concludes with a discussion of avenues for further research. 1. Introduction The precise meaning of ‘experimental philosophy’ is a matter of controversy even among its practitioners, but all agree that it refers to a movement which employs the methods of empirical science to shed light on philosophical debates. Most commonly, experimental philosophers attempt to probe ordinary intuitions about a particular case or question in hopes of learning about the psychological processes that underlie these intuitions (Knobe 2007).1 The unifying conviction behind the movement is that many deep philosophical problems ‘can only be properly addressed by immersing oneself in the messy, contingent, highly variable truths about how human beings really are’.2 And the problem that has received the most attention from experimental philosophers thus far is the problem of free will.