RETHINKING EMPIRICISM and MATERIALISM:THE REVISIONIST VIEW Charles Wolfe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Western Philosophy Rev

Designed by John Cornet, Phoenix HS (Ore) Western Philosophy rev. September 2012 The very process of philosophy has been a driving force in the tranformation of the world. From the figure who dwells upon how to achieve power, to the minister who contemplates the paradox of the only truth (their faith) yet which is also stagnent, to the astronomers who are searching the stars for signs of other civilizations, to the revolutionaries who sought to construct a national government which would protect the rights of the minority, the very exercise of philosophy and philosophical thought is at a core of human nature. Philosophy addresses what are sometimes called the "big questions." These include questions of morality and ethics, ideology/faith,, politics, the truth of knowledge, the nature of reality, and the meaning of human existance (...just to name a few!) (Religion addresses some of the same questions, but while philosophy and religion overlap in some questions, they can and do differ significantly in the approach they take to answering them.) Subject Learning Outcomes Skills-Based Learning Outcomes Behavioral Expectations and Grading Policy Develop an appreciation for and enjoyment of Organize, maintain and learn how to study from a learning, particularly in how learning should subject-specific notebook Attendance, participation and cause us to question what we think we know Be able to demonstrate how to take notes (including being prepared are daily and have a willingness to entertain new utilizing two-column format) expectations perspectives on issues. Be able to engage in meaningful, substantive discussion A classroom culture of respect and Students will develop familiarity with major with others. -

May 12, 2017 Department of Philosophy Undergraduate Course Descriptions

UB Spring Session January 30 - May 12, 2017 Department of Philosophy Undergraduate Course Descriptions PHI 101 Introduction to Philosophy K. Cho M, W, F, 9:00 AM-9:50 AM Class # 24095 This is an introductory philosophy course with a compact and yet global design. Instead of the frequently adopted but seldom fully utilized textbooks averaging 630 pates we have chosen a text with only 130 ages but packed with content that is literally “Global”. Text: John Dewey, Confucius and Global Philosophy, by Joseph Grange, 2004, SUNY Press; Plus Occasional Handouts in class. The choice of the two names Dewey and Confucius is more symbolic. Nobody would think these two embody the Western half and The Eastern half of the world; philosophy it is rather in terms of “working connections” they reveal to each other that we perceive them as representatives of our age it its needs. Dewey was certainly a typical American philosopher, who like no one else. Advanced the cause of Pragmatism. But he was also the American philosopher who was the most open to the world. He lectured in Beijing and promoted talented Chinese scholars who came to seek his guidance. And who remembers today that Dewey was thoroughly at home in Kant’s, Kant's Critique and was a skilled Hegelian dialectician? “Breathing is an affair as much as it is an affair of the air”. Or “Walking is an affair of legs as much as it is an affair of the earth.” In these simple words, Dewy translated the speculative language of German Idealism and made philosophy an affair of living. -

1 the Concept of the Self in David Hume and the Buddha

The Concept of the Self in David Hume and the Buddha Desh Raj Sirswal The concept of the self is a highly contested topic. Traditionally it belonged to speculative metaphysics. Almost every philosopher, whether Western or Indian, has tried to explore the nature of self. Generally, the self is taken as a substance which has permanent existence, which is eternal and non-specio-temporal. In some traditions, like the Hindu tradition, it is believed to take rebirth as the body perishes. Many Western philosophers also think that it is immortal. The nature of the self also has then ethical implications. The views of David Hume and Gautama Buddha on the self, which I have chosen to discuss here, are similar. Though both belong to different traditions, both are skeptical of any permanent existence of self. This is not to say that one has borrowed from the other. For the nature and purpose of denial of the self in both the philosophers is different. So a comprehensive and comparative study of their views is very interesting. It is the intention of this article to analyze and compare the philosophical positions of Gautama and Hume on the self—a problem which was of central concern to both and which has since exercised a continuing fascination for philosophers, both of the East and the West. Analysis of Hume’s Views on Self According to empiricism, human intellect and experiences are limited; so we cannot know of the absolute. David Hume, an eminent empiricist, concludes that the self is merely a composition of successive impressions. -

Religious Worldviews*

RELIGIOUS WORLDVIEWS* SECULAR POLITICAL CHRISTIANITY ISLAM MARXISM HUMANISM CORRECTNESS Nietzsche/Rorty Sources Koran, Hadith Humanist Manifestos Marx/Engels/Lenin/Mao/ The Bible Foucault/Derrida, Frankfurt Sunnah I/II/ III Frankfurt School Subjects School Theism Theism Atheism Atheism Atheism THEOLOGY (Trinitarian) (Unitarian) PHILOSOPHY Correspondence/ Pragmatism/ Pluralism/ Faith/Reason Dialectical Materialism (truth) Faith/Reason Scientism Anti-Rationalism Moral Relativism Moral Absolutes Moral Absolutes Moral Relativism Proletariat Morality (foster victimhood & ETHICS (Individualism) (Collectivism) (Collectivism) (Collectivism) /Collectivism) Creationism Creationism Naturalism Naturalism Naturalism (Intelligence, Time, Matter, (Intelligence, Time Matter, ORIGIN SCIENCE (Time/Matter/Energy) (Time/Matter/Energy) (Time/Matter/Energy) Energy) Energy) 1 Mind/Body Dualism Monism/self-actualization Socially constructed self Monism/behaviorism Mind/Body Dualism (fallen) PSYCHOLOGY (non fallen) (tabula rasa) Monism (tabula rasa) (tabula rasa) Traditional Family/Church/ Polygamy/Mosque & Nontraditional Family/statist Destroy Family, church and Classless Society/ SOCIOLOGY State State utopia Constitution Anti-patriarchy utopia Critical legal studies Proletariat law Divine/natural law Shari’a Positive law LAW (Positive law) (Positive law) Justice, freedom, order Global Islamic Theocracy Global Statism Atomization and/or Global & POLITICS Sovereign Spheres Ummah Progressivism Anarchy/social democracy Stateless Interventionism & Dirigisme Stewardship -

1 Forthcoming in Oxford Studies in Experimental Philosophy Causal Reasoning

Forthcoming in Oxford Studies in Experimental Philosophy Causal Reasoning: Philosophy and Experiment* James Woodward History and Philosophy of Science University of Pittsburgh 1. Introduction The past few decades have seen much interesting work, both within and outside philosophy, on causation and allied issues. Some of the philosophy is understood by its practitioners as metaphysics—it asks such questions as what causation “is”, whether there can be causation by absences, and so on. Other work reflects the interests of philosophers in the role that causation and causal reasoning play in science. Still other work, more computational in nature, focuses on problems of causal inference and learning, typically with substantial use of such formal apparatuses as Bayes nets (e.g. , Pearl, 2000, Spirtes et al, 2001) or hierarchical Bayesian models (e.g. Griffiths and Tenenbaum, 2009). All this work – the philosophical and the computational -- might be described as “theoretical” and it often has a strong “normative” component in the sense that it attempts to describe how we ought to learn, reason, and judge about causal relationships. Alongside this normative/theoretical work, there has also been a great deal of empirical work (hereafter Empirical Research on Causation or ERC) which focuses on how various subjects learn causal relationships, reason and judge causally. Much of this work has been carried out by psychologists, but it also includes contributions by primatologists, researchers in animal learning, and neurobiologists, and more rarely, philosophers. In my view, the interactions between these two groups—the normative/theoretical and the empirical -- has been extremely fruitful. In what follows, I describe some ideas about causal reasoning that have emerged from this research, focusing on the “interventionist” ideas that have figured in my own work. -

Existentialism, Phenomenology, and Education James Magrini College of Dupage, [email protected]

College of DuPage [email protected]. Philosophy Scholarship Philosophy 7-1-2012 Existentialism, Phenomenology, and Education James Magrini College of DuPage, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://dc.cod.edu/philosophypub Part of the Education Commons, and the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Magrini, James, "Existentialism, Phenomenology, and Education" (2012). Philosophy Scholarship. Paper 30. http://dc.cod.edu/philosophypub/30 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Philosophy at [email protected].. It has been accepted for inclusion in Philosophy Scholarship by an authorized administrator of [email protected].. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Existentialism, Phenomenology, and Education James M. Magrini Existentialism, and specifically phenomenology, in qualitative educational research, tends to be misunderstood. There are many reasons for this, not the least of which is that scholars/researchers writing in the field often emulate and imitate the dense writing styles of philosophical forerunners in phenomenology such as Hegel, Brentano, Husserl, Heidegger, and Merleau-Ponty. Thus the writing is beyond the comprehension of many education professionals and practitioners. Existentialism and phenomenology need not be highly complex. Here I provide a summary of existentialism and phenomenology in accessible terms so that educators might see the potential this type of philosophy holds for enhancing our educational endeavors. 1. Existentialism is a modern philosophy emerging (existence-philosophy) from the 19th century, inspired by such thinkers as Kierkegaard and Nietzsche. Unlike traditional philosophy, which focuses on “objective” instances of truth, existentialism is concerned with the subjective, or personal, aspects of existence. -

Descartes' Influence in Shaping the Modern World-View

R ené Descartes (1596-1650) is generally regarded as the “father of modern philosophy.” He stands as one of the most important figures in Western intellectual history. His work in mathematics and his writings on science proved to be foundational for further development in these fields. Our understanding of “scientific method” can be traced back to the work of Francis Bacon and to Descartes’ Discourse on Method. His groundbreaking approach to philosophy in his Meditations on First Philosophy determine the course of subsequent philosophy. The very problems with which much of modern philosophy has been primarily concerned arise only as a consequence of Descartes’thought. Descartes’ philosophy must be understood in the context of his times. The Medieval world was in the process of disintegration. The authoritarianism that had dominated the Medieval period was called into question by the rise of the Protestant revolt and advances in the development of science. Martin Luther’s emphasis that salvation was a matter of “faith” and not “works” undermined papal authority in asserting that each individual has a channel to God. The Copernican revolution undermined the authority of the Catholic Church in directly contradicting the established church doctrine of a geocentric universe. The rise of the sciences directly challenged the Church and seemed to put science and religion in opposition. A mathematician and scientist as well as a devout Catholic, Descartes was concerned primarily with establishing certain foundations for science and philosophy, and yet also with bridging the gap between the “new science” and religion. Descartes’ Influence in Shaping the Modern World-View 1) Descartes’ disbelief in authoritarianism: Descartes’ belief that all individuals possess the “natural light of reason,” the belief that each individual has the capacity for the discovery of truth, undermined Roman Catholic authoritarianism. -

Experimental Philosophy, Robert Kane, and the Concept of Free Will

Journal of Cognition and Neuroethics Experimental Philosophy, Robert Kane, and the Concept of Free Will J. Neil Otte University at Buffalo, The State University of New York Biography J. Neil Otte is presently in the Ph.D. program at the University at Buffalo (SUNY) and works in moral psychology, cognitive science, and the history of philosophy. For six years, he was an adjunct lecturer in philosophy at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City. In the last three years, he has been an organizer of the Buffalo Annual Experimental Philosophy Conference, an organizer for a conference on sentiment and reason in early modern philosophy, and has worked as an ontologist for the research foundation, CUBRC. Acknowledgements The author wishes to thank Gunnar Björnsson, Gregg Caruso, and Oisín Deery for their supportive comments and conversation during the Free Will Conference at the Insight Institute of Neurosurgery and Neuroscience in Fall of 2014, as well as conference organizer Jami Anderson. Publication Details Journal of Cognition and Neuroethics (ISSN: 2166-5087). March, 2015. Volume 3, Issue 1. Citation Otte, J. Neil. 2015. “Experimental Philosophy, Robert Kane, and the Concept of Free Will.” Journal of Cognition and Neuroethics 3 (1): 281–296. Experimental Philosophy, Robert Kane, and the Concept of Free Will J. Neil Otte Abstract Trends in experimental philosophy have provided new and compelling results that are cause for re-evaluations in contemporary discussions of free will. In this paper, I argue for one such re-evaluation by criticizing Robert Kane’s well-known views on free will. I argue that Kane’s claims about pre-theoretical intuitions are not supported by empirical findings on two accounts. -

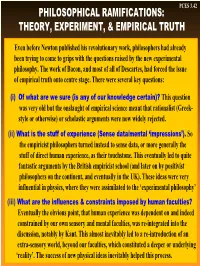

Philosophical Ramifications: Theory, Experiment, & Empirical Truth

PCES 3.42 PHILOSOPHICAL RAMIFICATIONS: THEORY, EXPERIMENT, & EMPIRICAL TRUTH Even before Newton published his revolutionary work, philosophers had already been trying to come to grips with the questions raised by the new experimental philosophy. The work of Bacon, and most of all of Descartes, had forced the issue of empirical truth onto centre stage. There were several key questions: (i) Of what are we sure (is any of our knowledge certain)? This question was very old but the onslaught of empirical science meant that rationalist (Greek- style or otherwise) or scholastic arguments were now widely rejected. (ii) What is the stuff of experience (Sense data/mental ‘impressions’). So the empiricist philosophers turned instead to sense data, or more generally the stuff of direct human experience, as their touchstone. This eventually led to quite fantastic arguments by the British empiricist school (and later on by positivist philosophers on the continent, and eventually in the UK). These ideas were very influential in physics, where they were assimilated to the ‘experimental philosophy’ (iii) What are the influences & constraints imposed by human faculties? Eventually the obvious point, that human experience was dependent on and indeed constrained by our own sensory and mental faculties, was re-integrated into the discussion, notably by Kant. This almost inevitably led to a re-introduction of an extra-sensory world, beyond our faculties, which constituted a deeper or underlying ‘reality’. The success of new physical ideas inevitably helped this process. PCES 3.43 BRITISH EMPIRICISM I: Locke & “Sensations” Locke was the first British philosopher of note after Bacon; his work is a reaction to the European rationalists, and continues to elaborate ‘experimental philosophy’. -

HURON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE Philosophy 2202G: Early Modern Philosophy 2017-2018

HURON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE Philosophy 2202G: Early Modern Philosophy 2017-2018 Winter Term, 2018 Instructor: Dr. Steve Bland Prerequisites: none Office: A304 Tuesdays, 10:30-12:30pm, V207 Office hours: Thursdays, 12:30-2:30pm Thursdays, 11:30-12:30pm, V207 Email: [email protected] The Early Modern period (ca. 1600-1800) was one of the most fruitful and exciting eras in the history of philosophy and science. New methods of inquiry and theories of the universe and the mind marked a radical shift away from medieval philosophy and towards a novel philosophical landscape of ideas. This course will provide an introductory survey of the philosophical theories of some of the most well known and influential thinkers of the Early Modern age, including: Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz, Locke, Berkeley, and Hume. In reading and discussing some of the classic primary works of these philosophers, we will become engaged in the following topics: scepticism, the nature of reality and the mind, the existence of god, free will, and personal identity. More generally, this course will focus on the crucially important rationalism- empiricism debate, which concerned not only the source of knowledge, but the proper method of answering philosophical questions. In other words, we will canvass Early Modern philosophical theories in an effort to answer the question: how should philosophy be done? COURSE LEARNING OBJECTIVES On successful completion of this course, students will be able to: 1. Clearly formulate and explain the central philosophical theories discussed in this course. 2. Reformulate complex arguments found within primary sources. 3. Defend a plausible position on the question of the origins of philosophical knowledge. -

Experimental Philosophy Jordan Kiper, Stephen Stich, H. Clark Barrett

Experimental Philosophy Jordan Kiper, Stephen Stich, H. Clark Barrett, & Edouard Machery Kiper, J., Stich, S., Barrett, H.C., & Machery, E. (in press). Experimental philosophy. In D. Ludwig, I. Koskinen, Z. Mncube, L. Poliseli, & L. Reyes-Garcia (Eds.), Global Epistemologies and Philosophies of Science. New York, NY: Routledge. Acknowledgments: This publication was made possible through the support of a grant from the John Templeton Foundation. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the John Templeton Foundation. Abstract Philosophers have argued that some philosophical concepts are universal, but it is increasingly clear that the question of philosophical universals is far from settled, and that far more cross- cultural research is necessary. In this chapter, we illustrate the relevance of investigating philosophical concepts and describe results from recent cross-cultural studies in experimental philosophy. We focus on the concept of knowledge and outline an ongoing project, the Geography of Philosophy Project, which empirically investigates the concepts of knowledge, understanding, and wisdom across cultures, languages, religions, and socioeconomic groups. We outline questions for future research on philosophical concepts across cultures, with an aim towards resolving questions about universals and variation in philosophical concepts. 1 Introduction For centuries, thinkers have urged that fundamental philosophical concepts, such as the concepts of knowledge or right and wrong, are universal or at least shared by all rational people (e.g., Plato 1892/375 BCE; Kant, 1998/1781; Foot, 2003). Yet many social scientists, in particular cultural anthropologists (e.g., Boas, 1940), but also continental philosophers such as Foucault (1969) have remained skeptical of these claims. -

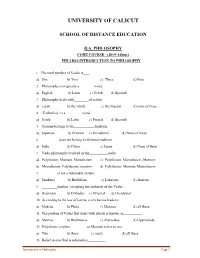

Introduction to Philosophy

UNIVERSITY OF CALICUT SCHOOL OF DISTANCE EDUCATION B.A. PHILOSOPHY CORE COURSE - (2019-Admn.) PHL1 B01-INTRODUCTION TO PHILOSOPHY 1. The total number of Vedas is . a) One b) Two c) Three d) Four 2. Philosophy is originally a word. a) English b) Latin c) Greek d) Spanish 3. Philosophy deals with of reality. a) a part b) the whole c) the illusion d) none of these 4. ‘Esthetikos’ is a word. a) Greek b) Latin c) French d) Spanish 5. Taoism belongs to the tradition. a) Japanese b) Oriental c) Occidental d) None of these 6. does not belong to Oriental tradition. a) India b) China c) Japan d) None of these 7. Vedic philosophy evolved in the order. a) Polytheism, Monism, Monotheism c) Polytheism, Monotheism, Monism b) Monotheism, Polytheism, monism d) Polytheism, Monism, Monotheism 8. is not a heterodox system. a) Samkhya b) Buddhism c) Lokayata d) Jainism 9. implies ‘accepting the authority of the Vedas’. a) Heterodox b) Orthodox c) Oriental d) Occidental 10. According to the law of karma, every karma leads to . a) Moksha b) Phala c) Dharma d) all these 11. The portion of Vedas that deals with rituals is known as . a) Mantras b) Brahmanas c) Aranyakas d) Upanishads 12. Polytheism implies as Monism refers to one. a) Two b) three c) many d) all these 13. Belief in one God is referred as . Introduction to Philosophy Page 1 a) Henotheism b) Monotheism c) Monism d) Polytheism 14. Samkhya propounded . a) Dualism b) Monism c) Monotheism d) Polytheism 15. is an Oriental system.