David Hume Has Been Largely Read As a Philosopher but Not As a Scientist

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The ”EXPERIMENTAL PHILOSOPHY”: Francis Bacon (1561-1626 AD)

1 The "EXPERIMENTAL PHILOSOPHY": Francis Bacon (1561-1626 AD) One of the most remarkable products of the reaction against Aristotelian philosophy, in the form that was handed down by late Mediaeval philosophers, was the rise of an entirely new philosophical system which came to be called 'Empiricism". This was particularly associated with British philosophers, and was both instrumental in the rise of modern science, and a by-product of it. Its ¯rst major exponent was Francis Bacon - although he was certainly influenced by earlier ideas (for example, from Roger Bacon) his ideas were very new in many cases, and had a very large influence on later work by British scientists. Later on Locke (a friend of Newton's) took it much further, and subsequently Berkeley and Hume took the whole idea of empiricism to an extreme. Although Bacon's contribution was the earliest and in some respects the crudest approach, in some ways it was the most durable, and certainly it had the largest impact on the development of science. LIFE of FRANCIS BACON Francis Bacon was born in London on January 22, 1561, at York House o® the Strand. He was the younger of two sons of Sir Nicholas Bacon, a successful lawyer and Lord Keeper of the Great Seal under Queen Elisabeth I. His mother Anne was a scholar, daughter of Sir Anthony Cooke, who translated ecclesiastical material from Italian and Latin into English; she was also a zealous Puritan. Bacon's father hoped Francis would become a diplomat and taught him the ways of a courtier. His aunt was married to William Cecil, later to become Lord Burghley, the most important ¯gure in Elisabeth's government. -

How Fun Are Your Meetings? Investigating the Relationship Between Humor Patterns in Team Interactions and Team Performance

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Psychology Faculty Publications Department of Psychology 11-2014 How fun are your meetings? Investigating the relationship between humor patterns in team interactions and team performance Nale Lehmann-Willenbrock Vrije University Amsterdam Joseph A. Allen University of Nebraska at Omaha, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/psychfacpub Part of the Industrial and Organizational Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Lehmann-Willenbrock, Nale and Allen, Joseph A., "How fun are your meetings? Investigating the relationship between humor patterns in team interactions and team performance" (2014). Psychology Faculty Publications. 118. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/psychfacpub/118 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Psychology at DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Psychology Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. In press at Journal of Applied Psychology How fun are your meetings? Investigating the relationship between humor patterns in team interactions and team performance Nale Lehmann-Willenbrock1 & Joseph A. Allen2 1 VU University Amsterdam 2 University of Nebraska at Omaha Acknowledgements The initial data collection for this study was partially supported by a grant from the German Research Foundation, which is gratefully acknowledged. We appreciate the support by Simone Kauffeld and the helpful feedback by Steve Kozlowski. Abstract Research on humor in organizations has rarely considered the social context in which humor occurs. One such social setting that most of us experience on a daily basis concerns the team context. Building on recent theorizing about the humor—performance association in teams, this study seeks to increase our understanding of the function and effects of humor in team interaction settings. -

Spring-And-Summer-Fun-Pack.Pdf

Spring & Summer FUN PACK BUILD OUR KIDS' SUCCESS Find many activities for kids in Kindergarten through Grade 9 to get moving and stay busy during the warmer months. Spring & Summer FUN PACK WHO IS THIS BOOKLET FOR? 1EVERYONE – kids, parents, camps, childcare providers, and anyone that is involved with kids this summer. BOKS has compiled a Spring & Summer Fun Pack that is meant to engage kids and allow them to “Create Their Own Adventure of Fun” for the warmer weather months. This package is full of easy to follow activities for kids to do independently, as a family, or for camp counselors/childcare providers to engage kids on a daily basis. We have included a selection of: BOKS Bursts (5–10 minute activity breaks) BOKS lesson plans - 30 minutes of fun interactive lessons including warm ups, skill work, games and nutrition bits with video links Crafts Games Recipes HOW DOES THIS WORK? Choose two or three activities daily from the selection outlined on page 4: 1. Get physically active with Bursts and/or BOKS fitness classes. 2. Be creative with cooking and crafts. 3. Have fun outdoors (or indoors), try our games! How do your kids benefit? • Give kids time to play and have fun. • Get kids moving toward their 60 minutes of recommended daily activity. • Build strong bones and muscles with simple fitness skills. • Reduce symptoms of anxiety. • Encourage a love of physical activity through engaging games. • We encourage your kids to have fun creating their own BOKS adventure. WHO WE ARE… BOKS (Build Our Kids' Success) is a FREE physical activity program designed to get kids active and establish a lifelong commitment to health and fitness. -

1 Forthcoming in Oxford Studies in Experimental Philosophy Causal Reasoning

Forthcoming in Oxford Studies in Experimental Philosophy Causal Reasoning: Philosophy and Experiment* James Woodward History and Philosophy of Science University of Pittsburgh 1. Introduction The past few decades have seen much interesting work, both within and outside philosophy, on causation and allied issues. Some of the philosophy is understood by its practitioners as metaphysics—it asks such questions as what causation “is”, whether there can be causation by absences, and so on. Other work reflects the interests of philosophers in the role that causation and causal reasoning play in science. Still other work, more computational in nature, focuses on problems of causal inference and learning, typically with substantial use of such formal apparatuses as Bayes nets (e.g. , Pearl, 2000, Spirtes et al, 2001) or hierarchical Bayesian models (e.g. Griffiths and Tenenbaum, 2009). All this work – the philosophical and the computational -- might be described as “theoretical” and it often has a strong “normative” component in the sense that it attempts to describe how we ought to learn, reason, and judge about causal relationships. Alongside this normative/theoretical work, there has also been a great deal of empirical work (hereafter Empirical Research on Causation or ERC) which focuses on how various subjects learn causal relationships, reason and judge causally. Much of this work has been carried out by psychologists, but it also includes contributions by primatologists, researchers in animal learning, and neurobiologists, and more rarely, philosophers. In my view, the interactions between these two groups—the normative/theoretical and the empirical -- has been extremely fruitful. In what follows, I describe some ideas about causal reasoning that have emerged from this research, focusing on the “interventionist” ideas that have figured in my own work. -

Beauty on Display Plato and the Concept of the Kalon

BEAUTY ON DISPLAY PLATO AND THE CONCEPT OF THE KALON JONATHAN FINE Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2018 © 2018 Jonathan Fine All rights reserved ABSTRACT BEAUTY ON DISPLAY: PLATO AND THE CONCEPT OF THE KALON JONATHAN FINE A central concept for Plato is the kalon – often translated as the beautiful, fine, admirable, or noble. This dissertation shows that only by prioritizing dimensions of beauty in the concept can we understand the nature, use, and insights of the kalon in Plato. The concept of the kalon organizes aspirations to appear and be admired as beautiful for one’s virtue. We may consider beauty superficial and concern for it vain – but what if it were also indispensable to living well? By analyzing how Plato uses the concept of the kalon to contest cultural practices of shame and honour regulated by ideals of beauty, we come to see not only the tensions within the concept but also how attractions to beauty steer, but can subvert, our attempts to live well. TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgements ii 1 Coordinating the Kalon: A Critical Introduction 1 1 The Kalon and the Dominant Approach 2 2 A Conceptual Problem 10 3 Overview 24 2 Beauty, Shame, and the Appearance of Virtue 29 1 Our Ancient Contemporaries 29 2 The Cultural Imagination 34 3 Spirit and the Social Dimension of the Kalon 55 4 Before the Eyes of Others 82 3 Glory, Grief, and the Problem of Achilles 100 1 A Tragic Worldview 103 2 The Heroic Ideal 110 3 Disgracing Achilles 125 4 Putting Poikilia in its Place 135 1 Some Ambivalences 135 2 The Aesthetics of Poikilia 138 3 The Taste of Democracy 148 4 Lovers of Sights and Sounds 173 5 The Possibility of Wonder 182 5 The Guise of the Beautiful 188 1 A Psychological Distinction 190 2 From Disinterested Admiration to Agency 202 3 The Opacity of Love 212 4 Looking Good? 218 Bibliography 234 i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS “To do philosophy is to explore one’s own temperament,” Iris Murdoch suggested at the outset of “Of ‘God’ and ‘Good’”. -

The Role of Simplicity in Science and Theory. C

East Tennessee State University Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University Undergraduate Honors Theses Student Works 5-2013 It's Not So Simple: The Role of Simplicity in Science and Theory. C. R. Gregg East Tennessee State University Follow this and additional works at: https://dc.etsu.edu/honors Part of the Theory and Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Gregg, C. R., "It's Not So Simple: The Role of Simplicity in Science and Theory." (2013). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 97. https://dc.etsu.edu/honors/97 This Honors Thesis - Withheld is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Works at Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ East Tennessee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. IT’S NOT SO SIMPLE: THE ROLE OF SIMPLICITY IN SCIENCE AND THEORY Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of Honors By C. R. Gregg Philosophy Honors In Discipline Program East Tennessee State University May 3, 2013 (Updated) May 7, 2013 Dr. David Harker, Faculty Mentor Dr. Jeffrey Gold, Honors Coordinator Dr. Gary Henson, Faculty Reader Dr. Allen Coates, Faculty Reader Paul Tudico, Faculty Reader ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to sincerely thank: David Harker, my mentor and friend. Paul Tudico, who is largely responsible for my choice to pursue Philosophy. Leslie MacAvoy, without whom I would not be an HID student. Karen Kornweibel, for believing in me. Rebecca Pyles, for believing in me. Gary Henson and Allen Coates, for offering their time to serve as readers. -

Francis Bacon and the Late Renaissance Politics of Learning

chapter 12 Francis Bacon and the Late Renaissance Politics of Learning Richard Serjeantson Anthony Grafton’s contributions to our knowledge and understanding of the long European Renaissance are numerous and varied. But one that is espe- cially significant is his demonstration of the role played by humanistic learn- ing in the transformation of natural knowledge across the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. No longer do we see this period as witnessing the sepa- ration of two increasingly opposed cultures of scholarship and of science. On the contrary: the history and philology of the Renaissance had far-reaching consequences for the natural sciences.1 Indeed, some of the most cherished aspects of this era’s revolution in the sciences can now be seen to have had their origins in humanistic scholarly practices. We now know, for instance, that Francis Bacon’s epochal insistence that research into nature should be the work of collaborative research groups, rather than the preserve of solitary savants, had its roots in the collaborative labors of the team of Protestant ecclesiastical historians led at Magdeburg by Matthias Flacius Illyricus.2 Francis Bacon is also the subject of this contribution. One of the great mod- ern questions in the interpretation of his life and writings has concerned the relationship between his politics and his science. According to one perspec- tive, Bacon was a proponent of a “politics of science,” in which natural philoso- phy would support a powerful and well-governed British state.3 An opposite 1 Anthony Grafton, “Humanism, Magic and Science,” in The Impact of Humanism on Western Europe, ed. -

Experimental Philosophy, Robert Kane, and the Concept of Free Will

Journal of Cognition and Neuroethics Experimental Philosophy, Robert Kane, and the Concept of Free Will J. Neil Otte University at Buffalo, The State University of New York Biography J. Neil Otte is presently in the Ph.D. program at the University at Buffalo (SUNY) and works in moral psychology, cognitive science, and the history of philosophy. For six years, he was an adjunct lecturer in philosophy at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City. In the last three years, he has been an organizer of the Buffalo Annual Experimental Philosophy Conference, an organizer for a conference on sentiment and reason in early modern philosophy, and has worked as an ontologist for the research foundation, CUBRC. Acknowledgements The author wishes to thank Gunnar Björnsson, Gregg Caruso, and Oisín Deery for their supportive comments and conversation during the Free Will Conference at the Insight Institute of Neurosurgery and Neuroscience in Fall of 2014, as well as conference organizer Jami Anderson. Publication Details Journal of Cognition and Neuroethics (ISSN: 2166-5087). March, 2015. Volume 3, Issue 1. Citation Otte, J. Neil. 2015. “Experimental Philosophy, Robert Kane, and the Concept of Free Will.” Journal of Cognition and Neuroethics 3 (1): 281–296. Experimental Philosophy, Robert Kane, and the Concept of Free Will J. Neil Otte Abstract Trends in experimental philosophy have provided new and compelling results that are cause for re-evaluations in contemporary discussions of free will. In this paper, I argue for one such re-evaluation by criticizing Robert Kane’s well-known views on free will. I argue that Kane’s claims about pre-theoretical intuitions are not supported by empirical findings on two accounts. -

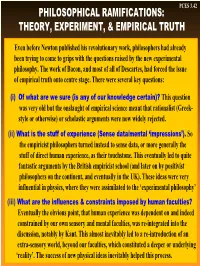

Philosophical Ramifications: Theory, Experiment, & Empirical Truth

PCES 3.42 PHILOSOPHICAL RAMIFICATIONS: THEORY, EXPERIMENT, & EMPIRICAL TRUTH Even before Newton published his revolutionary work, philosophers had already been trying to come to grips with the questions raised by the new experimental philosophy. The work of Bacon, and most of all of Descartes, had forced the issue of empirical truth onto centre stage. There were several key questions: (i) Of what are we sure (is any of our knowledge certain)? This question was very old but the onslaught of empirical science meant that rationalist (Greek- style or otherwise) or scholastic arguments were now widely rejected. (ii) What is the stuff of experience (Sense data/mental ‘impressions’). So the empiricist philosophers turned instead to sense data, or more generally the stuff of direct human experience, as their touchstone. This eventually led to quite fantastic arguments by the British empiricist school (and later on by positivist philosophers on the continent, and eventually in the UK). These ideas were very influential in physics, where they were assimilated to the ‘experimental philosophy’ (iii) What are the influences & constraints imposed by human faculties? Eventually the obvious point, that human experience was dependent on and indeed constrained by our own sensory and mental faculties, was re-integrated into the discussion, notably by Kant. This almost inevitably led to a re-introduction of an extra-sensory world, beyond our faculties, which constituted a deeper or underlying ‘reality’. The success of new physical ideas inevitably helped this process. PCES 3.43 BRITISH EMPIRICISM I: Locke & “Sensations” Locke was the first British philosopher of note after Bacon; his work is a reaction to the European rationalists, and continues to elaborate ‘experimental philosophy’. -

DISGUST: Features and SAWCHUK and Clinical Implications

Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, Vol. 24, No. 7, 2005, pp. 932-962 OLATUNJIDISGUST: Features AND SAWCHUK and Clinical Implications DISGUST: CHARACTERISTIC FEATURES, SOCIAL MANIFESTATIONS, AND CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS BUNMI O. OLATUNJI University of Massachusetts CRAIG N. SAWCHUK University of Washington School of Medicine Emotions have been a long–standing cornerstone of research in social and clinical psychology. Although the systematic examination of emotional processes has yielded a rather comprehensive theoretical and scientific literature, dramatically less empirical attention has been devoted to disgust. In the present article, the na- ture, experience, and other associated features of disgust are outlined. We also re- view the domains of disgust and highlight how these domains have expanded over time. The function of disgust in various social constructions, such as cigarette smoking, vegetarianism, and homophobia, is highlighted. Disgust is also becoming increasingly recognized as an influential emotion in the onset, maintenance, and treatment of various phobic states, Obsessive–Compulsive Disorder, and eating disorders. In comparison to the other emotions, disgust offers great promise for fu- ture social and clinical research efforts, and prospective studies designed to improve our understanding of disgust are outlined. The nature, structure, and function of emotions have a rich tradition in the social and clinical psychology literature (Cacioppo & Gardner, 1999). Although emotion theorists have contested over the number of discrete emotional states and their operational definitions (Plutchik, 2001), most agree that emotions are highly influential in organizing thought processes and behavioral tendencies (Izard, 1993; John- Preparation of this manuscript was supported in part by NIMH NRSA grant 1F31MH067519–1A1 awarded to Bunmi O. -

Francis Bacon: of Law, Science, and Philosophy Laurel Davis Boston College Law School, [email protected]

Boston College Law School Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School Rare Book Room Exhibition Programs Daniel R. Coquillette Rare Book Room Fall 9-1-2013 Francis Bacon: Of Law, Science, and Philosophy Laurel Davis Boston College Law School, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/rbr_exhibit_programs Part of the Archival Science Commons, European History Commons, and the Legal History Commons Digital Commons Citation Davis, Laurel, "Francis Bacon: Of Law, Science, and Philosophy" (2013). Rare Book Room Exhibition Programs. Paper 20. http://lawdigitalcommons.bc.edu/rbr_exhibit_programs/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Daniel R. Coquillette Rare Book Room at Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Rare Book Room Exhibition Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Boston College Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 Francis Bacon: Of Law, Science, and Philosophy Boston College Law Library Daniel R. Coquillette Rare Book Room Fall 2013 This exhibit was curated by Laurel Davis and features a selection of books from a beautiful and generous gift to us from J. Donald Monan Professor of Law Daniel R. Coquillette The catalog cover was created by Lily Olson, Law Library Assistant, from the frontispiece portrait in Bacon’s Of the Advancement and Proficiencie of Learn- ing: Or the Partitions of Sciences Nine Books. London: Printed for Thomas Williams at the Golden Ball in Osier Lane, 1674. The caption of the original image gives Bacon’s official title and states that he died in April 1626 at age 66. -

Altruism, Morality & Social Solidarity Forum

Altruism, Morality & Social Solidarity Forum A Forum for Scholarship and Newsletter of the AMSS Section of ASA Volume 3, Issue 2 May 2012 What’s so Darned Special about Church Friends? Robert D. Putnam Harvard University One purpose of my recent research (with David E. Campbell) on religion in America1 was to con- firm and, if possible, extend previous research on the correlation of religiosity and altruistic behavior, such as giving, volunteering, and community involvement. It proved straight-forward to show that each of sev- eral dozen measures of good neighborliness was strongly correlated with religious involvement. Continued on page 19... Our Future is Just Beginning Vincent Jeffries, Acting Chairperson California State University, Northridge The beginning of our endeavors has ended. The study of altruism, morality, and social solidarity is now an established section in the American Sociological Association. We will have our first Section Sessions at the 2012 American Sociological Association Meetings in Denver, Colorado, this August. There is a full slate of candidates for the ASA elections this spring, and those chosen will take office at the Meetings. Continued on page 4... The Revival of Russian Sociology and Studies of This Issue: Social Solidarity From the Editor 2 Dmitry Efremenko and Yaroslava Evseeva AMSS Awards 3 Institute of Scientific Information for Social Sciences, Russian Academy of Sciences Scholarly Updates 12 The article was executed in the framework of the research project Social solidarity as a condition of society transformations: Theoretical foundations, Bezila 16 Russian specificity, socio-biological and socio-psychological aspects, supported Dissertation by the Russian foundation for basic research (Project 11-06-00347а).