DAVID HUME the Essential DAVID HUME James R

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Is the Balance Between Certainty and Uncertainty?

What is the balance between certainty and uncertainty? Susan Griffin, Centre for Health Economics, University of York Overview • Decision analysis – Objective function – The decision to invest/disinvest in health care programmes – The decision to require further evidence • Characterising uncertainty – Epistemic uncertainty, quality of evidence, modelling uncertainty • Possibility for research Theory Objective function • Methods can be applied to any decision problem – Objective – Quantitative index measure of outcome • Maximise health subject to budget constraint – Value improvement in quality of life in terms of equivalent improvement in length of life → QALYs • Maximise health and equity s.t budget constraint – Value improvement in equity in terms of equivalent improvement in health The decision to invest • Maximise health subject to budget constraint – Constrained optimisation problem – Given costs and health outcomes of all available programmes, identify optimal set • Marginal approach – Introducing new programme displaces existing activities – Compare health gained to health forgone resources Slope gives rate at C A which resources converted to health gains with currently funded programmes health HGA HDA resources Slope gives rate at which resources converted to health gains with currently funded programmes CB health HDB HGB Requiring more evidence • Costs and health outcomes estimated with uncertainty • Cost of uncertainty: programme funded on basis of estimated costs and outcomes might turn out not to be that which maximises health -

Would ''Direct Realism'' Resolve the Classical Problem of Induction?

NOU^S 38:2 (2004) 197–232 Would ‘‘Direct Realism’’ Resolve the Classical Problem of Induction? MARC LANGE University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill I Recently, there has been a modest resurgence of interest in the ‘‘Humean’’ problem of induction. For several decades following the recognized failure of Strawsonian ‘‘ordinary-language’’ dissolutions and of Wesley Salmon’s elaboration of Reichenbach’s pragmatic vindication of induction, work on the problem of induction languished. Attention turned instead toward con- firmation theory, as philosophers sensibly tried to understand precisely what it is that a justification of induction should aim to justify. Now, however, in light of Bayesian confirmation theory and other developments in epistemology, several philosophers have begun to reconsider the classical problem of induction. In section 2, I shall review a few of these developments. Though some of them will turn out to be unilluminating, others will profitably suggest that we not meet inductive scepticism by trying to justify some alleged general principle of ampliative reasoning. Accordingly, in section 3, I shall examine how the problem of induction arises in the context of one particular ‘‘inductive leap’’: the confirmation, most famously by Henrietta Leavitt and Harlow Shapley about a century ago, that a period-luminosity relation governs all Cepheid variable stars. This is a good example for the inductive sceptic’s purposes, since it is difficult to see how the sparse background knowledge available at the time could have entitled stellar astronomers to regard their observations as justifying this grand inductive generalization. I shall argue that the observation reports that confirmed the Cepheid period- luminosity law were themselves ‘‘thick’’ with expectations regarding as yet unknown laws of nature. -

David Hume and the Origin of Modern Rationalism Donald Livingston Emory University

A Symposium: Morality Reconsidered David Hume and the Origin of Modern Rationalism Donald Livingston Emory University In “How Desperate Should We Be?” Claes Ryn argues that “morality” in modern societies is generally understood to be a form of moral rationalism, a matter of applying preconceived moral principles to particular situations in much the same way one talks of “pure” and “applied” geometry. Ryn finds a num- ber of pernicious consequences to follow from this rationalist model of morals. First, the purity of the principles, untainted by the particularities of tradition, creates a great distance between what the principles demand and what is possible in actual experience. The iridescent beauty and demands of the moral ideal distract the mind from what is before experience.1 The practical barriers to idealistically demanded change are oc- cluded from perception, and what realistically can and ought to be done is dismissed as insufficient. And “moral indignation is deemed sufficient”2 to carry the day in disputes over policy. Further, the destruction wrought by misplaced idealistic change is not acknowledged to be the result of bad policy but is ascribed to insufficient effort or to wicked persons or groups who have derailed it. A special point Ryn wants to make is that, “One of the dangers of moral rationalism and idealism is DONAL D LIVINGSTON is Professor of Philosophy Emeritus at Emory Univer- sity. 1 Claes Ryn, “How Desperate Should We Be?” Humanitas, Vol. XXVIII, Nos. 1 & 2 (2015), 9. 2 Ibid., 18. 44 • Volume XXVIII, Nos. 1 and 2, 2015 Donald Livingston that they set human beings up for desperation. -

1 Forthcoming in Oxford Studies in Experimental Philosophy Causal Reasoning

Forthcoming in Oxford Studies in Experimental Philosophy Causal Reasoning: Philosophy and Experiment* James Woodward History and Philosophy of Science University of Pittsburgh 1. Introduction The past few decades have seen much interesting work, both within and outside philosophy, on causation and allied issues. Some of the philosophy is understood by its practitioners as metaphysics—it asks such questions as what causation “is”, whether there can be causation by absences, and so on. Other work reflects the interests of philosophers in the role that causation and causal reasoning play in science. Still other work, more computational in nature, focuses on problems of causal inference and learning, typically with substantial use of such formal apparatuses as Bayes nets (e.g. , Pearl, 2000, Spirtes et al, 2001) or hierarchical Bayesian models (e.g. Griffiths and Tenenbaum, 2009). All this work – the philosophical and the computational -- might be described as “theoretical” and it often has a strong “normative” component in the sense that it attempts to describe how we ought to learn, reason, and judge about causal relationships. Alongside this normative/theoretical work, there has also been a great deal of empirical work (hereafter Empirical Research on Causation or ERC) which focuses on how various subjects learn causal relationships, reason and judge causally. Much of this work has been carried out by psychologists, but it also includes contributions by primatologists, researchers in animal learning, and neurobiologists, and more rarely, philosophers. In my view, the interactions between these two groups—the normative/theoretical and the empirical -- has been extremely fruitful. In what follows, I describe some ideas about causal reasoning that have emerged from this research, focusing on the “interventionist” ideas that have figured in my own work. -

2. Aristotle's Concept of the State

Page No.13 2. Aristotle's concept of the state Olivera Z. Mijuskovic Full Member International Association of Greek Philosophy University of Athens, Greece ORCID iD: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5950-7146 URL: http://worldphilosophynetwork.weebly.com E-Mail: [email protected] Abstract: In contrast to a little bit utopian standpoint offered by Plato in his teachings about the state or politeia where rulers aren`t “in love with power but in virtue”, Aristotle's teaching on the same subject seems very realistic and pragmatic. In his most important writing in this field called "Politics", Aristotle classified authority in the form of two main parts: the correct authority and moose authority. In this sense, correct forms of government are 1.basileus, 2.aristocracy and 3.politeia. These forms of government are based on the common good. Bad or moose forms of government are those that are based on the property of an individual or small governmental structures and they are: 1.tiranny, 2.oligarchy and 3.democracy. Also, Aristotle's political thinking is not separate from the ethical principles so he states that the government should be reflected in the true virtue that is "law" or the "golden mean". Keywords: Government; stat; , virtue; democracy; authority; politeia; golden mean. Vol. 4 No. 4 (2016) Issue- December ISSN 2347-6869 (E) & ISSN 2347-2146 (P) Aristotle's concept of the state by Olivera Z. Mijuskovic Page no. 13-20 Page No.14 Aristotle's concept of the state 1.1. Aristotle`s “Politics” Politics in its defined form becomes affirmed by the ancient Greek world. -

Developments in Neuroscience and Human Freedom: Some Theological and Philosophical Questions

S & CB (2003), 16, 123–137 0954–4194 ALAN TORRANCE Developments in Neuroscience and Human Freedom: Some Theological and Philosophical Questions Christianity suggests that human beings are free and responsible agents. Developments in neuroscience challenge this when wedded with two ‘fideisms’: ‘naturalism’ and ‘nomological monism’ (causality applies exclusively to basic particles). The wedding of Galen Strawson’s denial that anything can be a cause of itself with a physicalist account of brain states highlights the problem neuroscience poses for human freedom. If physicalism is inherently reductionistic (Kim) and dualism struggles to make sense of developments in neuroscience, Cartwright’s pluralist account of causality may offer a way forward. It integrates with thinking about the person from a Christian epistemic base and facilitates response to Strawson. Key Words: God, person, neuroscience, freedom, naturalism, nomological monism, physicalism, dualism, causality. Five years ago, the Ethics and Public Policy Center in Washington, hosted a conference on ‘Neuroscience and the Human Spirit’. In his opening address, the organiser, Dr Frederick Goodwin, asked whether developments in the field do not pose a challenge to the ‘very foundation upon which our civilization rests’, namely, ‘free will and the capacity to make moral choices?’ The question I am seeking to address here raises the same issue with respect to the grounds of the Christian understanding of its message and, indeed, of what it is to be a person. In the light of recent advances in understanding the physical workings of our neural substrate, the electrochemical nature of cerebral processing and so on, does it still make sense to conceive of our minds as the free cause of our actions and the conscious centre of human life? So much suggests that the workings of our minds require to be construed in radically physical and, apparently, imper- sonal terms – as a complex causal series of synaptic firings and the like. -

Experimental Philosophy, Robert Kane, and the Concept of Free Will

Journal of Cognition and Neuroethics Experimental Philosophy, Robert Kane, and the Concept of Free Will J. Neil Otte University at Buffalo, The State University of New York Biography J. Neil Otte is presently in the Ph.D. program at the University at Buffalo (SUNY) and works in moral psychology, cognitive science, and the history of philosophy. For six years, he was an adjunct lecturer in philosophy at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City. In the last three years, he has been an organizer of the Buffalo Annual Experimental Philosophy Conference, an organizer for a conference on sentiment and reason in early modern philosophy, and has worked as an ontologist for the research foundation, CUBRC. Acknowledgements The author wishes to thank Gunnar Björnsson, Gregg Caruso, and Oisín Deery for their supportive comments and conversation during the Free Will Conference at the Insight Institute of Neurosurgery and Neuroscience in Fall of 2014, as well as conference organizer Jami Anderson. Publication Details Journal of Cognition and Neuroethics (ISSN: 2166-5087). March, 2015. Volume 3, Issue 1. Citation Otte, J. Neil. 2015. “Experimental Philosophy, Robert Kane, and the Concept of Free Will.” Journal of Cognition and Neuroethics 3 (1): 281–296. Experimental Philosophy, Robert Kane, and the Concept of Free Will J. Neil Otte Abstract Trends in experimental philosophy have provided new and compelling results that are cause for re-evaluations in contemporary discussions of free will. In this paper, I argue for one such re-evaluation by criticizing Robert Kane’s well-known views on free will. I argue that Kane’s claims about pre-theoretical intuitions are not supported by empirical findings on two accounts. -

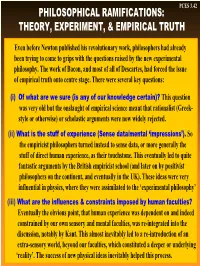

Philosophical Ramifications: Theory, Experiment, & Empirical Truth

PCES 3.42 PHILOSOPHICAL RAMIFICATIONS: THEORY, EXPERIMENT, & EMPIRICAL TRUTH Even before Newton published his revolutionary work, philosophers had already been trying to come to grips with the questions raised by the new experimental philosophy. The work of Bacon, and most of all of Descartes, had forced the issue of empirical truth onto centre stage. There were several key questions: (i) Of what are we sure (is any of our knowledge certain)? This question was very old but the onslaught of empirical science meant that rationalist (Greek- style or otherwise) or scholastic arguments were now widely rejected. (ii) What is the stuff of experience (Sense data/mental ‘impressions’). So the empiricist philosophers turned instead to sense data, or more generally the stuff of direct human experience, as their touchstone. This eventually led to quite fantastic arguments by the British empiricist school (and later on by positivist philosophers on the continent, and eventually in the UK). These ideas were very influential in physics, where they were assimilated to the ‘experimental philosophy’ (iii) What are the influences & constraints imposed by human faculties? Eventually the obvious point, that human experience was dependent on and indeed constrained by our own sensory and mental faculties, was re-integrated into the discussion, notably by Kant. This almost inevitably led to a re-introduction of an extra-sensory world, beyond our faculties, which constituted a deeper or underlying ‘reality’. The success of new physical ideas inevitably helped this process. PCES 3.43 BRITISH EMPIRICISM I: Locke & “Sensations” Locke was the first British philosopher of note after Bacon; his work is a reaction to the European rationalists, and continues to elaborate ‘experimental philosophy’. -

Humour in Nietzsche's Style

Received: 15 May 2020 Accepted: 25 July 2020 DOI: 10.1111/ejop.12585 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Humour in Nietzsche's style Charles Boddicker University of Southampton, Southampton, UK Abstract Correspondence Nietzsche's writing style is designed to elicit affective Charles Boddicker, University of responses in his readers. Humour is one of the most common Southampton, Avenue Campus, Highfield Road, Southampton SO17 1BF, UK. means by which he attempts to engage his readers' affects. In Email: [email protected] this article, I explain how and why Nietzsche uses humour to achieve his philosophical ends. The article has three parts. In part 1, I reject interpretations of Nietzsche's humour on which he engages in self-parody in order to mitigate the charge of decadence or dogmatism by undermining his own philosophi- cal authority. In part 2, I look at how Nietzsche uses humour and laughter as a critical tool in his polemic against traditional morality. I argue that one important way in which Nietzsche uses humour is as a vehicle for enhancing the effectiveness of his ad hominem arguments. In part 3, I show how Nietzsche exploits humour's social dimension in order to find and culti- vate what he sees as the right kinds of readers for his works. Nietzsche is a unique figure in Western philosophy for the importance he places on laughter and humour. He is also unique for his affectively charged style, a style frequently designed to make the reader laugh. In this article, I am pri- marily concerned with the way in which Nietzsche uses humour, but I will inevitably discuss some of his more theo- retical remarks on the topic, as these cannot be neatly separated. -

Kant's Doctrine of Religion As Political Philosophy

Kant's Doctrine of Religion as Political Philosophy Author: Phillip David Wodzinski Persistent link: http://hdl.handle.net/2345/987 This work is posted on eScholarship@BC, Boston College University Libraries. Boston College Electronic Thesis or Dissertation, 2009 Copyright is held by the author, with all rights reserved, unless otherwise noted. Boston College The Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Department of Political Science KANT’S DOCTRINE OF RELIGION AS POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY a dissertation by PHILLIP WODZINSKI submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2009 © copyright by PHILLIP DAVID WODZINSKI 2009 ABSTRACT Kant’s Doctrine of Religion as Political Philosophy Phillip Wodzinski Advisor: Susan Shell, Ph.D. Through a close reading of Immanuel Kant’s late book, Religion within the Boundaries of Mere Reason, the dissertation clarifies the political element in Kant’s doctrine of religion and so contributes to a wider conception of his political philosophy. Kant’s political philosophy of religion, in addition to extending and further animating his moral doctrine, interprets religion in such a way as to give the Christian faith a moral grounding that will make possible, and even be an agent of, the improvement of social and political life. The dissertation emphasizes the wholeness and structure of Religion within the Boundaries of Mere Reason as a book, for the teaching of the book is not exhausted by the articulation of its doctrine but also includes both the fact and the manner of its expression: the reader learns most fully from Kant by giving attention to the structure and tone of the book as well as to its stated content and argumentation. -

Humour and Caricature Teachers Notes Humour and Caricature

Humour and Caricature Teachers Notes Humour and Caricature “We all love a good political cartoon. Whether we agree with the underlying sentiment or not, the biting wit and the sharp insight of a well-crafted caricature and its punch line are always deeply satisfying.” Peter Greste, Australian Journalist, Behind the Lines 2015 Foreward POINTS FOR DISCUSSION: Consider the meaning of the phrases “biting wit”, “sharp insight”, “well-crafted caricature”. Look up definitions if required. Do you agree with Peter Greste that people find political cartoons “deeply satisfying” even if they don’t agree with the cartoons underlying sentiment? Why/why not? 2 Humour and Caricature What’s so funny? Humour is an important part of most political cartoons. It’s a very effective way for The joke cartoonists to communicate their message to their audience can be simple or — and thereby help shape public opinion. multi-layered and complex. POINTS FOR DISCUSSION: “By distilling political arguments and criticisms into Do a quick exercise with your classmates — share a couple clear, easily digestible (and at times grossly caricatured) of jokes. Does everyone understand them? Why/why not? statements, they have oiled our political debate and What does this tell us about humour? helped shape public opinion”. Peter Greste, Australian Journalist, Behind the Lines foreward, http://behindthelines.moadoph.gov.au/2015/foreword. Why do you believe it’s important for cartoonists to make their cartoons easy to understand? What are some limitations readers could encounter which may hinder their understanding of the overall message? 3 Humour and Caricature Types of humour Cartoonists use different kinds of humour to communicate their message — the most common are irony, satire and sarcasm. -

Logical Empiricism / Positivism Some Empiricist Slogans

4/13/16 Logical empiricism / positivism Some empiricist slogans o Hume’s 18th century book-burning passage Key elements of a logical positivist /empiricist conception of science o Comte’s mid-19th century rejection of n Motivations for post WW1 ‘scientific philosophy’ ‘speculation after first & final causes o viscerally opposed to speculation / mere metaphysics / idealism o Duhem’s late 19th/early 20th century slogan: o a normative demarcation project: to show why science ‘save the phenomena’ is and should be epistemically authoritative n Empiricist commitments o Hempel’s injunction against ‘detours n Logicism through the realm of unobservables’ Conflicts & Memories: The First World War Vienna Circle Maria Marchant o Debussy: Berceuse héroique, Élégie So - what was the motivation for this “revolutionary, written war-time Paris (1914), heralds the ominous bugle call of war uncompromising empricism”? (Godfrey Smith, Ch. 2) o Rachmaninov: Études-Tableaux Op. 39, No 8, 5 “some of the most impassioned, fervent work the composer wrote” Why the “massive intellectual housecleaning”? (Godfrey Smith) o Ireland: Rhapsody, London Nights, London Pieces a “turbulant, virtuosic work… Consider the context: World War I / the interwar period o Prokofiev: Visions Fugitives, Op. 22 written just before he fled as a fugitive himself to the US (1917); military aggression & sardonic irony o Ravel: Le Tombeau de Couperin each of six movements dedicated to a friend who died in the war x Key problem (1): logicism o Are there, in fact, “rules” governing inference