Experimental Philosophy of Aesthetics

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Forthcoming in Oxford Studies in Experimental Philosophy Causal Reasoning

Forthcoming in Oxford Studies in Experimental Philosophy Causal Reasoning: Philosophy and Experiment* James Woodward History and Philosophy of Science University of Pittsburgh 1. Introduction The past few decades have seen much interesting work, both within and outside philosophy, on causation and allied issues. Some of the philosophy is understood by its practitioners as metaphysics—it asks such questions as what causation “is”, whether there can be causation by absences, and so on. Other work reflects the interests of philosophers in the role that causation and causal reasoning play in science. Still other work, more computational in nature, focuses on problems of causal inference and learning, typically with substantial use of such formal apparatuses as Bayes nets (e.g. , Pearl, 2000, Spirtes et al, 2001) or hierarchical Bayesian models (e.g. Griffiths and Tenenbaum, 2009). All this work – the philosophical and the computational -- might be described as “theoretical” and it often has a strong “normative” component in the sense that it attempts to describe how we ought to learn, reason, and judge about causal relationships. Alongside this normative/theoretical work, there has also been a great deal of empirical work (hereafter Empirical Research on Causation or ERC) which focuses on how various subjects learn causal relationships, reason and judge causally. Much of this work has been carried out by psychologists, but it also includes contributions by primatologists, researchers in animal learning, and neurobiologists, and more rarely, philosophers. In my view, the interactions between these two groups—the normative/theoretical and the empirical -- has been extremely fruitful. In what follows, I describe some ideas about causal reasoning that have emerged from this research, focusing on the “interventionist” ideas that have figured in my own work. -

Hegel-Jahrbuch 2010 Hegel- Jahrbuch 2010

Hegel-Jahrbuch 2010 Hegel- Jahrbuch 2010 Begründet von Wilhelm Raimund Beyer (f) Herausgegeben von Andreas Arndt Paul Cruysberghs Andrzej Przylebski in Verbindung mit Lu De Vos und Peter Jonkers Geist? Erster Teil Herausgegeben von Andreas Arndt Paul Cruysberghs Andrzej Przylebski in Verbindung mit Lu De Vos und Peter Jonkers Akademie Verlag Redaktionelle Mitarbeit: Veit Friemert Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. ISBN 978-3-05-004638-9 © Akademie Verlag GmbH, Berlin 2010 Das eingesetzte Papier ist alterungsbeständig nach DIN/ISO 9706. Alle Rechte, insbesondere die der Übersetzung in andere Sprachen, vorbehalten. Kein Teil dieses Buches darf ohne schriftliche Genehmigung des Verlages in irgendeiner Form - durch Photokopie, Mikroverfilmung oder irgendein anderes Verfahren - reproduziert oder in eine von Maschinen, insbesondere von Datenver- arbeitungsmaschinen, verwendbare Sprache übertragen oder übersetzt werden. Lektorat: Mischka Dammaschke Satz: Veit Friemert, Berlin Einbandgestaltung: nach einem Entwurf von Günter Schorcht, Schildow Druck: MB Medienhaus Berlin Printed in the Federal Republic of Germany VORWORT Das vorliegende Hegel-Jahrbuch umfasst den ersten Teil der auf dem XXVII. Internationalen He- gel-Kongress der Internationalen Hegel-Gesellschaft e.V. 2008 in Leuven zum Thema »Geist?« gehaltenen Referate. Den Dank an alle Förderer und Helfer, die den Kongress ermöglicht und zu dessen Gelingen beigetragen haben, hat Paul Cruysberghs - der zusammen mit Lu de Vos und Peter Jonkers das örtliche Organisationskomitee bildete - in seiner im folgenden abgedruckten Eröff- nungsrede abgestattet; ihm schließt sich der übrige Vorstand mit einem besonderen Dank an Paul Cruysberghs an. -

What Is the Cognitive Neuroscience of Art… and Why Should We Care? W

What Is the Cognitive Neuroscience of Art… and Why Should We Care? W. P. Seeley Bates College There has been considerable interest in recent years in whether, and if so to what degree, research in neuroscience can contribute to philosophical studies of mind, epistemology, language, and art. This interest has manifested itself in a range of research in the philosophy of music, dance, and visual art that draws on results from studies in neuropsychology and cognitive neuroscience.1 There has been a concurrent movement within empirical aesthet- ics that has produced a growing body of research in the cognitive neuroscience of art.2 However, there has been very little collaboration between philosophy and the neuroscience of art. This is in part due, to be frank, to a culture of mutual distrust. Philosophers of art AMERICAN SOCIETY have been generally skeptical about the utility of empirical results to their research and vocally dismissive of the value of what has come to be called neuroaesthetics. Our counter- for AESThetics parts in the behavioral sciences have been, in turn, skeptical about the utility of stubborn philosophical skepticism. Of course attitudes change…and who has the time to hold a An Association for Aesthetics, grudge? So in what follows I would like to draw attention to two questions requisite for Criticism and Theory of the Arts a rapprochement between philosophy of art and neuroscience. First, what is the cognitive neuroscience of art? And second, why should any of us (in philosophy at least) care? Volume 31 Number 2 Summer 2011 1 What Is the Cognitive Neuroscience of There are obvious answers to each of these questions. -

Experimental Philosophy, Robert Kane, and the Concept of Free Will

Journal of Cognition and Neuroethics Experimental Philosophy, Robert Kane, and the Concept of Free Will J. Neil Otte University at Buffalo, The State University of New York Biography J. Neil Otte is presently in the Ph.D. program at the University at Buffalo (SUNY) and works in moral psychology, cognitive science, and the history of philosophy. For six years, he was an adjunct lecturer in philosophy at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City. In the last three years, he has been an organizer of the Buffalo Annual Experimental Philosophy Conference, an organizer for a conference on sentiment and reason in early modern philosophy, and has worked as an ontologist for the research foundation, CUBRC. Acknowledgements The author wishes to thank Gunnar Björnsson, Gregg Caruso, and Oisín Deery for their supportive comments and conversation during the Free Will Conference at the Insight Institute of Neurosurgery and Neuroscience in Fall of 2014, as well as conference organizer Jami Anderson. Publication Details Journal of Cognition and Neuroethics (ISSN: 2166-5087). March, 2015. Volume 3, Issue 1. Citation Otte, J. Neil. 2015. “Experimental Philosophy, Robert Kane, and the Concept of Free Will.” Journal of Cognition and Neuroethics 3 (1): 281–296. Experimental Philosophy, Robert Kane, and the Concept of Free Will J. Neil Otte Abstract Trends in experimental philosophy have provided new and compelling results that are cause for re-evaluations in contemporary discussions of free will. In this paper, I argue for one such re-evaluation by criticizing Robert Kane’s well-known views on free will. I argue that Kane’s claims about pre-theoretical intuitions are not supported by empirical findings on two accounts. -

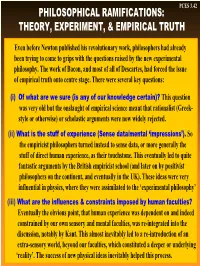

Philosophical Ramifications: Theory, Experiment, & Empirical Truth

PCES 3.42 PHILOSOPHICAL RAMIFICATIONS: THEORY, EXPERIMENT, & EMPIRICAL TRUTH Even before Newton published his revolutionary work, philosophers had already been trying to come to grips with the questions raised by the new experimental philosophy. The work of Bacon, and most of all of Descartes, had forced the issue of empirical truth onto centre stage. There were several key questions: (i) Of what are we sure (is any of our knowledge certain)? This question was very old but the onslaught of empirical science meant that rationalist (Greek- style or otherwise) or scholastic arguments were now widely rejected. (ii) What is the stuff of experience (Sense data/mental ‘impressions’). So the empiricist philosophers turned instead to sense data, or more generally the stuff of direct human experience, as their touchstone. This eventually led to quite fantastic arguments by the British empiricist school (and later on by positivist philosophers on the continent, and eventually in the UK). These ideas were very influential in physics, where they were assimilated to the ‘experimental philosophy’ (iii) What are the influences & constraints imposed by human faculties? Eventually the obvious point, that human experience was dependent on and indeed constrained by our own sensory and mental faculties, was re-integrated into the discussion, notably by Kant. This almost inevitably led to a re-introduction of an extra-sensory world, beyond our faculties, which constituted a deeper or underlying ‘reality’. The success of new physical ideas inevitably helped this process. PCES 3.43 BRITISH EMPIRICISM I: Locke & “Sensations” Locke was the first British philosopher of note after Bacon; his work is a reaction to the European rationalists, and continues to elaborate ‘experimental philosophy’. -

Experimental Philosophy Jordan Kiper, Stephen Stich, H. Clark Barrett

Experimental Philosophy Jordan Kiper, Stephen Stich, H. Clark Barrett, & Edouard Machery Kiper, J., Stich, S., Barrett, H.C., & Machery, E. (in press). Experimental philosophy. In D. Ludwig, I. Koskinen, Z. Mncube, L. Poliseli, & L. Reyes-Garcia (Eds.), Global Epistemologies and Philosophies of Science. New York, NY: Routledge. Acknowledgments: This publication was made possible through the support of a grant from the John Templeton Foundation. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the John Templeton Foundation. Abstract Philosophers have argued that some philosophical concepts are universal, but it is increasingly clear that the question of philosophical universals is far from settled, and that far more cross- cultural research is necessary. In this chapter, we illustrate the relevance of investigating philosophical concepts and describe results from recent cross-cultural studies in experimental philosophy. We focus on the concept of knowledge and outline an ongoing project, the Geography of Philosophy Project, which empirically investigates the concepts of knowledge, understanding, and wisdom across cultures, languages, religions, and socioeconomic groups. We outline questions for future research on philosophical concepts across cultures, with an aim towards resolving questions about universals and variation in philosophical concepts. 1 Introduction For centuries, thinkers have urged that fundamental philosophical concepts, such as the concepts of knowledge or right and wrong, are universal or at least shared by all rational people (e.g., Plato 1892/375 BCE; Kant, 1998/1781; Foot, 2003). Yet many social scientists, in particular cultural anthropologists (e.g., Boas, 1940), but also continental philosophers such as Foucault (1969) have remained skeptical of these claims. -

Chad Van Schoelandt

CHAD VAN SCHOELANDT Tulane University Department of Philosophy, New Orleans, LA [email protected] Employment 2015-present Assistant Professor, Tulane University, Department of Philosophy 2016-present Affiliated Fellow, George Mason University, F. A. HayeK Program for Advanced Study in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics Areas of Specialization Social and Political Philosophy Ethics Agency and Responsibility Philosophy, Politics & Economics Areas of Competence Applied Ethics (esp. Business, Environmental, Bio/Medical) History of Modern Philosophy Moral Psychology Education Ph.D., University of Arizona, Philosophy, 2015 M.A., University of Wisconsin - MilwauKee, Philosophy, 2010 B.A. (High Honors), University of California, Davis, Philosophy (political science minor), 2006 Publications Articles “Moral Accountability and Social Norms” Social Philosophy & Policy, Vol. 35, Issue 1, Spring 2018 “Consensus on What? Convergence for What? Four Models of Political Liberalism” (with Gerald Gaus) Ethics, Vol. 128, Issue 1, 2017: pp. 145-72 “Justification, Coercion, and the Place of Public Reason” Philosophical Studies, 172, 2015: pp. 1031-1050 “MarKets, Community, and Pluralism” The Philosophical Quarterly, Discussion, 64(254), 2014: pp. 144-151 "Political Liberalism, Ethos Justice, and Gender Equality" (with Blain Neufeld) Law and Philosophy 33(1), 2014: pp. 75-104 Chad Van Schoelandt CV Page 2 of 4 Book Chapters “A Public Reason Approach to Religious Exemption” Philosophy and Public Policy, Andrew I. Cohen (ed.), Rowman and Littlefield International, -

Cv Langsam.Pdf

CV Harold Langsam Professor of Philosophy Corcoran Department of Philosophy 120 Cocke Hall University of Virginia P.O. Box 400780 Charlottesville, VA 22904-4780 (434) 924-6920 (Office) (434) 979-2880 (Home) [email protected] Employment: Professor of Philosophy, University of Virginia (2011-) Associate Professor of Philosophy, University of Virginia (2001-2011). Assistant Professor of Philosophy, University of Virginia (1994-2001). Mellon Postdoctoral Teaching and Research Fellow, Department of Philosophy, Cornell University (1994-95). Publications: Book The Wonder of Consciousness: Understanding the Mind through Philosophical Reflection (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2011). Reviews: Ethics and Medicine, Mind, Notre Dame Philosophical Reviews, Philosophical Quarterly Articles “McDowell’s Infallibilism and the Nature of Knowledge,” Synthese, http://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-020-02682-4. “Why Intentionalism Cannot Explain Phenomenal Character,” Erkenntnis 85 (2020): 375-389. “Nietzsche and Value Creation: Subjectivism, Self-Expression, and Strength,” Inquiry 61 (2018): 100-113. “The Intuitive Case for Naïve Realism,” Philosophical Explorations 20 (2017): 106-122. “A Defense of McDowell’s Response to the Sceptic,” Acta Analytica 29 (2014): 43-59. “A Defense of Restricted Phenomenal Conservatism,” Philosophical Papers 42 (2013): 315-340. "Rationality, Justification, and the Internalism/Externalism Debate," Erkenntnis 68 (2008): 79- 101. "Why I Believe in an External World," Metaphilosophy 37 (2006): 652-672. "Consciousness, Experience, and Justification," Canadian Journal of Philosophy 32 (2002): 1- 28. "Externalism, Self-Knowledge, and Inner Observation," Australasian Journal of Philosophy 80 (2002): 42-61. "Strategy for Dualists," Metaphilosophy 32 (2001): 395-418. "Pain, Personal Identity, and the Deep Further Fact," Erkenntnis 54 (2001): 247-271. "Experiences, Thoughts, and Qualia," Philosophical Studies 99 (2000): 269-295. -

Neuroaesthetics of Art Vision: an Experimental Approach to the Sense of Beauty

Cl n l of i ica a l T rn r u ia o l s J ISSN: 2167-0870 Journal of Clinical Trials Research Article Neuroaesthetics of Art Vision: An Experimental Approach to the Sense of Beauty Maddalena Coccagna1, PietroAvanzini2, Mariagrazia Portera4, Giovanni Vecchiato2, Maddalena Fabbri Destro2, AlessandroVittorio Sironi3,9, Fabrizio Salvi8, Andrea Gatti5, Filippo Domenicali5, Raffaella Folgieri3,6, Annalisa Banzi3, Caselli Elisabetta1, Luca Lanzoni1, Volta Antonella1, Matteo Bisi1, Silvia Cesari1, Arianna Vivarelli1, Giorgio Balboni Pier1, Giuseppe Santangelo Camillo1, Giovanni Sassu7, Sante Mazzacane1* 1Department of CIAS Interdepartmental Research Center, University of Ferrara, Ferrara, Italy;2Department of CNR Neuroscience Institute, Parma, Italy;3Department of CESPEB Neuroaesthetics Laboratory, University Bicocca, Milan, Italy;4Department of Letters and Philosophy, University of Florence, Italy;5Department of Humanistic Studies, University of Ferrara, Ferrara, Italy;6Department of Philosophy Piero Martinetti, University La Statale, Milan, Italy;7Department of Musei Arte Antica, Ferrara, Italy;8Department of Neurological Sciences, Bellaria Hospital, Bologna, Italy;9Department of Centre of the history of Biomedical Thought, University Bicocca, Milan, Italy ABSTRACT Objective: NEVArt research aims to study the correlation between a set of neurophysiological/emotional reactions and the level of aesthetic appreciation of around 500 experimental subjects, during the observation of 18 different paintings from the XVI-XVIII century, in a real museum context. Methods: Several bio-signals have been recorded to evaluate the participants’ reactions during the observation of paintings. Among them: (a) neurovegetative, motor and emotional biosignals were recorded using wearable tools for EEG (electroencephalogram), ECG (electrocardiogram) and EDA (electrodermal activity); (b) gaze pattern during the observation of art works, while (c) data of the participants (age, gender, education, familiarity with art, etc.) and their explicit judgments about paintings have been obtained. -

Christian Martin – Publikationen

Christian Martin – Publikationen (Stand: September 2020) Buchveröffentlichungen Monographien Die Einheit des Sinns. Untersuchungen zur Form des Denkens und Sprechens. Paderborn: Mentis, 2020. [689 Seiten] Ontologie der Selbstbestimmung. Eine operationale Rekonstruktion von Hegels „Wissenschaft der Logik“. Tübingen: Mohr/Siebeck, 2012. [692 Seiten] Herausgeberschaft Language, Form(s) of Life, and Logic: Investigations after Wittgenstein (= Series: On Wittgenstein, Vol. 4). Berlin/New York: de Gruyter, 2018. [342 Seiten] Aufsätze 1. Aufsätze in Zeitschriften Ursprünge transzendentaler Ästhetik. Zum Wandel von Kants Raum- und Zeitargumentation von der Inauguraldissertation zur „Kritik“, in: Kant-Studien 111:3 (2020), 331-385. Kant on Concepts, Intuitions, and the Continuity of Space, in: Idealistic Studies 50:3 (2020), 121-146. On Redrawing the Force-Content Distinction, in: Nordic Wittgenstein Review 8:1-2 (2019), 175-208. Hegel on the Undefinabiliy of Truth and the Absoluteness of Spirit, in: Idealistic Studies 47 (2017), 191-217. Hegel on Judgments and Posits, in: Hegel-Bulletin 37:1 (2016), 53-80. Poetry as a Form of Knowledge, in: SATS: Northern European Journal of Philosophy 17:2 (2016), 159-184. Wittgenstein on Perspicuous Presentations and Grammatical Self-Knowledge, in: Nordic Wittgenstein Review 5:1 (2016), 79-108. Four Types of Conceptual Generality, in: Graduate Faculty Philosophy Journal 36:2 (2015), 397423. Heideggers Physis-Denken, in: Philosophisches Jahrbuch 116 (2009), 90114. 2. Aufsätze in Büchern Functions and Operations: Wittgenstein versus Frege and Russell, erscheint in: James Conant und Gilad Nir (Hrsg.): Early Analytic Philosophy: A Collection of Critical Essays. [ca. 25. Seiten]. 1 Imagination and the Proper Object of Perception, erscheint in: James Conant und Jonas Held (Hrsg.): The Palgrave Handbook of German Idealism and Analytic Philosophy [ca. -

Aisthesis in Radical Empiricism: Gustav Fechner's Psychophysics

Aisthesis in Radical Empiricism: Gustav Fechner’s Psychophysics and Experimental Aesthetics Jay Hetrick* Universiteit van Amsterdam Abstract. The purpose of this paper is to situate the work of Gustav Fechner within the tradition of radical empiricism in order to sketch the beginnings of a truly post-Kantian theory of empirical aesthet- ics. Although Fechner inaugurates this trajectory of radical empiri- cism, especially with his ideas on psychophysics and experimental aesthetics, he seems to naively disregard Kant by adopting the Pla- tonic relation of aisthesis to pleasure and pain as well as the Wolf- fian relation of pleasure to beauty. Nonetheless, his work paves the way for other philosophers — most notably William James, Henri Bergson, and Gilles Deleuze — who to different degrees take into consideration the Kantian intervention. Fechner’s work, considered as a whole, helps us to redefine aesthetics as the radical-empirical science of aisthesis. For radical empiricism, what is ultimately inter- esting is neither sensation, understood in its psychological or collo- quial meanings, nor experience, including even aesthetic or religions experience. The real object of this science of aisthesis is, as Deleuze states, precisely that which is encountered in a psychophysical shock to thought: “not an aistheton but an aistheteon ... not a sensible being but the being of the sensible.” In 1876, Gustav Fechner — a German physicist, philosopher of nature, and founder of experimental psychology — published a provocative two- volume work entitled Vorschule der Aesthetik. The premise of this “Pre- school” was that aesthetics must proceed, like any other science, from the bottom up, by utilizing empirical data to develop aesthetic concepts in- ductively. -

Experimental Philosophy and the Compatibility of Free Will and Determinism: a Survey

Annals of the Japan Association for Philosophy of Science Vol.22 (2014) 17~37 17 Experimental Philosophy and the Compatibility of Free Will and Determinism: A Survey Florian Cova∗ and Yasuko Kitano∗∗ Abstract The debate over whether free will and determinism are compatible is con- troversial, and produces wide scholarly discussion. This paper argues that recent studies in experimental philosophy suggest that people are in fact “natural com- patibilists”. To support this claim, it surveys the experimental literature bearing directly (section 1) or indirectly (section 2) upon this issue, before pointing to three possible limitations of this claim (section 3). However, notwithstanding these limitations, the investigation concludes that the existing empirical evidence seems to support the view that most people have compatibilist intuitions. Key words: experimental philosophy; free will; moral responsibility; determin- ism Introduction The recently developed field of experimental philosophy advocates a methodolog- ical shift toward the use of an experimental methodology, in order to make progress on problems in philosophy (Knobe and Nichols, 2008). On a narrow view, experimen- tal philosophy is an experimental investigation of our intuitions about philosophical issues; on a larger view, it encompasses all tentative attempts to make progress on philosophical questions using experimental methods (Cova, 2012). Recently, a growing number of studies in experimental philosophy are addressing the relationship between free will and moral responsibility. Most of these aim (i) at testing whether people have the intuition that an agent in a deterministic universe cannot have free will and be morally responsible for his or her actions by (ii) probing their intuitions on small vignettes1.