What Is the Cognitive Neuroscience of Art… and Why Should We Care? W

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Distancing-Embracing Model of the Enjoyment of Negative Emotions in Art Reception

BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (2017), Page 1 of 63 doi:10.1017/S0140525X17000309, e347 The Distancing-Embracing model of the enjoyment of negative emotions in art reception Winfried Menninghaus1 Department of Language and Literature, Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics, 60322 Frankfurt am Main, Germany [email protected] Valentin Wagner Department of Language and Literature, Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics, 60322 Frankfurt am Main, Germany [email protected] Julian Hanich Department of Arts, Culture and Media, University of Groningen, 9700 AB Groningen, The Netherlands [email protected] Eugen Wassiliwizky Department of Language and Literature, Max Planck Institute for Empirical Aesthetics, 60322 Frankfurt am Main, Germany [email protected] Thomas Jacobsen Experimental Psychology Unit, Helmut Schmidt University/University of the Federal Armed Forces Hamburg, 22043 Hamburg, Germany [email protected] Stefan Koelsch University of Bergen, 5020 Bergen, Norway [email protected] Abstract: Why are negative emotions so central in art reception far beyond tragedy? Revisiting classical aesthetics in the light of recent psychological research, we present a novel model to explain this much discussed (apparent) paradox. We argue that negative emotions are an important resource for the arts in general, rather than a special license for exceptional art forms only. The underlying rationale is that negative emotions have been shown to be particularly powerful in securing attention, intense emotional involvement, and high memorability, and hence is precisely what artworks strive for. Two groups of processing mechanisms are identified that conjointly adopt the particular powers of negative emotions for art’s purposes. -

Processing Fluency and Aesthetic Pleasure: Is Beauty in the Perceiver’S Processing Experience?

Personality and Social Psychology Review Copyright © 2004 by 2004, Vol. 8, No. 4, 364–382 Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. Processing Fluency and Aesthetic Pleasure: Is Beauty in the Perceiver’s Processing Experience? Rolf Reber Department of Psychosocial Science University of Bergen, Norway Norbert Schwarz Department of Psychology and Institute for Social Research University of Michigan Piotr Winkielman Department of Psychology University of California, San Diego We propose that aesthetic pleasure is a function of the perceiver’s processing dynam- ics: The more fluently perceivers can process an object, the more positive their aes- thetic response. We review variables known to influence aesthetic judgments, such as figural goodness, figure–ground contrast, stimulus repetition, symmetry, and pro- totypicality, and trace their effects to changes in processing fluency. Other variables that influence processing fluency, like visual or semantic priming, similarly increase judgments of aesthetic pleasure. Our proposal provides an integrative framework for the study of aesthetic pleasure and sheds light on the interplay between early prefer- ences versus cultural influences on taste, preferences for both prototypical and ab- stracted forms, and the relation between beauty and truth. In contrast to theories that trace aesthetic pleasure to objective stimulus features per se, we propose that beauty is grounded in the processing experiences of the perceiver, which are in part a func- tion of stimulus properties. What is beauty? What makes for a beautiful face, kiewicz, 1970). This objectivist view inspired many appealing painting, pleasing design, or charming scen- psychological attempts to identify the critical contrib- ery? This question has been debated for at least 2,500 utors to beauty. -

Neuroaesthetics of Art Vision: an Experimental Approach to the Sense of Beauty

Cl n l of i ica a l T rn r u ia o l s J ISSN: 2167-0870 Journal of Clinical Trials Research Article Neuroaesthetics of Art Vision: An Experimental Approach to the Sense of Beauty Maddalena Coccagna1, PietroAvanzini2, Mariagrazia Portera4, Giovanni Vecchiato2, Maddalena Fabbri Destro2, AlessandroVittorio Sironi3,9, Fabrizio Salvi8, Andrea Gatti5, Filippo Domenicali5, Raffaella Folgieri3,6, Annalisa Banzi3, Caselli Elisabetta1, Luca Lanzoni1, Volta Antonella1, Matteo Bisi1, Silvia Cesari1, Arianna Vivarelli1, Giorgio Balboni Pier1, Giuseppe Santangelo Camillo1, Giovanni Sassu7, Sante Mazzacane1* 1Department of CIAS Interdepartmental Research Center, University of Ferrara, Ferrara, Italy;2Department of CNR Neuroscience Institute, Parma, Italy;3Department of CESPEB Neuroaesthetics Laboratory, University Bicocca, Milan, Italy;4Department of Letters and Philosophy, University of Florence, Italy;5Department of Humanistic Studies, University of Ferrara, Ferrara, Italy;6Department of Philosophy Piero Martinetti, University La Statale, Milan, Italy;7Department of Musei Arte Antica, Ferrara, Italy;8Department of Neurological Sciences, Bellaria Hospital, Bologna, Italy;9Department of Centre of the history of Biomedical Thought, University Bicocca, Milan, Italy ABSTRACT Objective: NEVArt research aims to study the correlation between a set of neurophysiological/emotional reactions and the level of aesthetic appreciation of around 500 experimental subjects, during the observation of 18 different paintings from the XVI-XVIII century, in a real museum context. Methods: Several bio-signals have been recorded to evaluate the participants’ reactions during the observation of paintings. Among them: (a) neurovegetative, motor and emotional biosignals were recorded using wearable tools for EEG (electroencephalogram), ECG (electrocardiogram) and EDA (electrodermal activity); (b) gaze pattern during the observation of art works, while (c) data of the participants (age, gender, education, familiarity with art, etc.) and their explicit judgments about paintings have been obtained. -

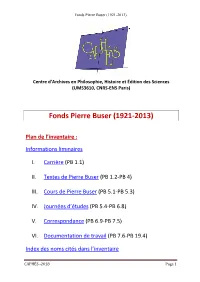

Archives De Pierre Buser

Fonds Pierre Buser (1921-2013) Centre d’Archives en Philosophie, Histoire et Édition des Sciences (UMS3610, CNRS-ENS Paris) Fonds Pierre Buser (1921-2013) Plan de l’inventaire : Informations liminaires I. Carrière (PB 1.1) II. Textes de Pierre Buser (PB 1.2-PB 4) III. Cours de Pierre Buser (PB 5.1-PB 5.3) IV. Journées d’études (PB 5.4-PB 6.8) V. Correspondance (PB 6.9-PB 7.5) VI. Documentation de travail (PB 7.6-PB 19.4) Index des noms cités dans l’inventaire CAPHÉS -2018 Page 1 Fonds Pierre Buser (1921-2013) Biographie : Notice issue du site de l’Académie des sciences Pierre Buser, né le 19 août 1921 est décédé le 29 décembre 2013. Il avait été élu correspondant de l'Académie le 4 février 1980, puis membre le 6 juin 1988 dans la section actuellement dénommée Biologie intégrative. Ancien élève de l'École normale supérieure, il était professeur émérite à l'Université Pierre-et-Marie-Curie. Neurophysiologiste, il fut un des fondateurs, en France et dans le monde, de la physiologie intégrative moderne du système nerveux. Il appartenait à l'École de neurophysiologie du comportement qui poursuit ses investigations dans le champ de la psychophysiologie et des fonctions infiniment complexes du cerveau. Avec lui, c'est le maître de toute une génération de neurobiologistes qui [a disparu]. Pierre Buser a consacré ses travaux à la neurophysiologie et à la psychophysiologie. Il [a poursuivi] ses investigations dans le champ infiniment complexe des fonctions du cerveau. Les travaux de Pierre Buser se sont de façon permanente centrés autour des activités électrophysiologiques du cerveau, comme marqueurs de son activité, en liaison avec le comportement de l’animal. -

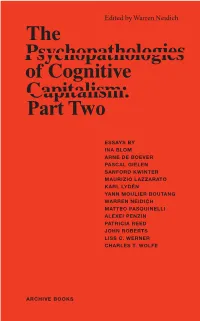

Edited by Warren Neidich

Part Two Final File First Edition_cover part two 5/21/14 9:43 PM Pagina 2 Edited by Warren Neidich ESSAYS BY INA BLOM ARNE DE BOEVER PASCAL GIELEN SANFORD KWINTER MAURIZIO LAZZARATO KARL LYDÉN YANN MOULIER BOUTANG WARREN NEIDICH MATTEO PASQUINELLI ALEXEI PENZIN PATRICIA REED JOHN ROBERTS LISS C. WERNER CHARLES T. WOLFE ARCHIVE BOOKS VOX SERIES Edited by Warren Neidich ESSAYS BY INA BLOM ARNE DE BOEVER PASCAL GIELEN SANFORD KWINTER MAURIZIO LAZZARATO KARL LYDÉN YANN MOULIER BOUTANG WARREN NEIDICH MATTEO PASQUINELLI ALEXEI PENZIN PATRICIA REED JOHN ROBERTS LISS C. WERNER CHARLES T. WOLFE ARCHIVE BOOKS This book collects together extended papers that were presented at The Psychopathologies of Cognitive Capitalism: Part Two at ICI Berlin in March 2013. This volume is the second in a series of book that aims attempts to broaden the definition of cognitive capitalism in terms of the scope of its material relations, especially as it relates to the condi- tions of mind and brain in our new world of advanced telecommunica- tion, data mining and social relations. It is our hope to first improve awa- reness of its most repressive charac- teristics and secondly to produce an arsenal of discursive practices with which to combat it. Edited by Warren Neidich Coordinating editor Nicola Guy Proofreading by Theo Barry-Born Designed by Archive Appendix, Berlin Printed by Erredi, Genova Published by Archive Books Dieffenbachstraße 31 10967 Berlin www.archivebooks.org ISBN 978-3-943620-16-0 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Warren Neidich The Early and Late Stages of Cognitive Capitalism .................................... 9 SECTION 1 Cognitive Capitalism The Early Phase Ina Blom Video and Autobiography vs. -

Aisthesis in Radical Empiricism: Gustav Fechner's Psychophysics

Aisthesis in Radical Empiricism: Gustav Fechner’s Psychophysics and Experimental Aesthetics Jay Hetrick* Universiteit van Amsterdam Abstract. The purpose of this paper is to situate the work of Gustav Fechner within the tradition of radical empiricism in order to sketch the beginnings of a truly post-Kantian theory of empirical aesthet- ics. Although Fechner inaugurates this trajectory of radical empiri- cism, especially with his ideas on psychophysics and experimental aesthetics, he seems to naively disregard Kant by adopting the Pla- tonic relation of aisthesis to pleasure and pain as well as the Wolf- fian relation of pleasure to beauty. Nonetheless, his work paves the way for other philosophers — most notably William James, Henri Bergson, and Gilles Deleuze — who to different degrees take into consideration the Kantian intervention. Fechner’s work, considered as a whole, helps us to redefine aesthetics as the radical-empirical science of aisthesis. For radical empiricism, what is ultimately inter- esting is neither sensation, understood in its psychological or collo- quial meanings, nor experience, including even aesthetic or religions experience. The real object of this science of aisthesis is, as Deleuze states, precisely that which is encountered in a psychophysical shock to thought: “not an aistheton but an aistheteon ... not a sensible being but the being of the sensible.” In 1876, Gustav Fechner — a German physicist, philosopher of nature, and founder of experimental psychology — published a provocative two- volume work entitled Vorschule der Aesthetik. The premise of this “Pre- school” was that aesthetics must proceed, like any other science, from the bottom up, by utilizing empirical data to develop aesthetic concepts in- ductively. -

Connecting and Separating Mind-Sets: Culture As Situated Cognition

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology © 2009 American Psychological Association 2009, Vol. 97, No. 2, 217–235 0022-3514/09/$12.00 DOI: 10.1037/a0015850 Connecting and Separating Mind-Sets: Culture as Situated Cognition Daphna Oyserman and Nicholas Sorensen Rolf Reber University of Michigan University of Bergen Sylvia Xiaohua Chen Hong Kong Polytechnic University People perceive meaningful wholes and later separate out constituent parts (D. Navon, 1977). Yet there are cross-national differences in whether a focal target or integrated whole is first perceived. Rather than construe these differences as fixed, the proposed culture-as-situated-cognition model explains these differences as due to whether a collective or individual mind-set is cued at the moment of observation. Eight studies demonstrated that when cultural mind-set and task demands are congruent, easier tasks are accomplished more quickly and more difficult or time-constrained tasks are accomplished more accu- rately (Study 1: Koreans, Korean Americans; Study 2: Hong Kong Chinese; Study 3: European- and Asian-heritage Americans; Study 4: Americans; Study: 5 Hong Kong Chinese; Study 6: Americans; Study 7: Norwegians; Study 8: African-, European-, and Asian-heritage Americans). Meta-analyses (d ϭ .34) demonstrated homogeneous effects across geographic place (East–West), racial–ethnic group, task, and sensory mode—differences are cued in the moment. Contrast and separation are salient individual mind-set procedures, resulting in focus on a single target or main point. Assimilation and connection are salient collective mind-set procedures, resulting in focus on multiplicity and integration. Keywords: culture, individualism, collectivism, independent, interdependent Everyone should understand this in this way. -

The Epistemic Status of Processing Fluency As Source for Judgments of Truth

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Rev.Phil.Psych. (2010) 1:563–581 DOI 10.1007/s13164-010-0039-7 The Epistemic Status of Processing Fluency as Source for Judgments of Truth Rolf Reber & Christian Unkelbach Published online: 7 September 2010 # The Author(s) 2010. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract This article combines findings from cognitive psychology on the role of processing fluency in truth judgments with epistemological theory on justification of belief. We first review evidence that repeated exposure to a statement increases the subjective ease with which that statement is processed. This increased processing fluency, in turn, increases the probability that the statement is judged to be true. The basic question discussed here is whether the use of processing fluency as a cue to truth is epistemically justified. In the present analysis, based on Bayes’ Theorem, we adopt the reliable-process account of justification presented by Goldman (1986) and show that fluency is a reliable cue to truth, under the assumption that the majority of statements one has been exposed to are true. In the final section, we broaden the scope of this analysis and discuss how processing fluency as a potentially universal cue to judged truth may contribute to cultural differences in commonsense beliefs. It was Napoleon, I believe, who said that there is only one figure in rhetoric of serious importance, namely, repetition. The thing affirmed comes by repetition to fix itself in the mind in such a way that it is accepted in the end as a demonstrated truth. -

Neuroaesthetics: a Coming of Age Story

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Neuroethics Publications Center for Neuroscience & Society 1-2011 Neuroaesthetics: A Coming of Age Story Anjan Chatterjee University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/neuroethics_pubs Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Chatterjee, A. (2011). Neuroaesthetics: A Coming of Age Story. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 23 (1), 53-62. http://dx.doi.org/10.1162/jocn.2010.21457 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/neuroethics_pubs/58 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Neuroaesthetics: A Coming of Age Story Abstract Neuroaesthetics is gaining momentum. At this early juncture, it is worth taking stock of where the field is and what lies ahead. Here, I review writings that fall under the rubric of neuroaesthetics. These writings include discussions of the parallel organizational principles of the brain and the intent and practices of artists, the description of informative anecdotes, and the emergence of experimental neuroaesthetics. I then suggest a few areas within neuroaesthetics that might be pursued profitably. Finally, I raise some challenges for the field. These challenges are not unique to neuroaesthetics. As neuroaesthetics comes of age, it might take advantage of the lessons learned from more mature domains of inquiry within cognitive neuroscience. Disciplines Medicine and Health Sciences Comments This journal article is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/neuroethics_pubs/58 Neuroaesthetics: A Coming of Age Story Anjan Chatterjee Abstract ■ Neuroaesthetics is gaining momentum. At this early junc- gence of experimental neuroaesthetics. I then suggest a few areas ture, it is worth taking stock of where the field is and what lies within neuroaesthetics that might be pursued profitably. -

Processing Fluency in Education: How Metacognitive Feelings Shape Learning, Belief Formation, and Affect

FLUENCY IN EDUCATION 1 Please cite as: Reber, R., & Greifeneder, R. (2017). Processing Fluency in Education: How Metacognitive Feelings Shape Learning, Belief Formation, and Affect. Educational Psychologist, 52(2), 84-103. doi: 10.1080/00461520.2016.1258173 Processing Fluency in Education: How Metacognitive Feelings Shape Learning, Belief Formation, and Affect Rolf Reber Department of Psychology, University of Oslo Rainer Greifeneder Department of Psychology, University of Basel Correspondence address: Rolf Reber, University of Oslo, Department of Psychology, Postboks 1094 Blindern, N-0317 Oslo, Norway. E-mail: [email protected] Acknowledgements: Rolf Reber has been supported by the Utdanning2020-program of the Norwegian Research Council (grant #212299). FLUENCY IN EDUCATION 2 Abstract Processing fluency – the experienced ease with which a mental operation is performed – has attracted little attention in educational psychology, despite its relevance. The present article reviews and integrates empirical evidence on processing fluency that is relevant to school education. Fluency is important, for instance, in learning, self-assessment of knowledge, testing, grading, teacher-student communication, social interaction in the multicultural classroom, and emergence of interest. After a brief overview of basic fluency research we review effects of processing fluency in three broad areas, namely metacognition in learning, belief formation, and affect. Within each area, we provide evidence-based implications for education. Along the way, we offer fluency-based insights into phenomena that were long known but not yet sufficiently explained (e.g., the effect of handwriting on grading). Bringing fluency (back) to education may contribute to research and school practice alike. FLUENCY IN EDUCATION 3 In the last decades, school education systems in many countries have been inspired by central tenets of cognitive psychology. -

Aesthetic Experts*

[Vol. 8/ 1] 2019 Aesthetic Experts Tereza Hadravová; [email protected], https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3255297 _______________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________ Abstract: In the 1990s and early 2000s, researchers in the field of so-called neuoaesthetics recruited research subjects who had been untrained in arts and did not have any pronounced interest in aesthetic matters for their laboratory experiments. The prevalent choice of research subjects has recently changed. Currently, a great number of studies uses subjects who are professionally engaged in the art world. In my paper, I describe, analyze, and critically discuss the two research paradigms regarding the subjects involved in the experiments in neuroaesthetics. I claim that although the more recent one can be generally regarded as an improvement of the research framework, it underestimates the difficulties brought by the notion of expertise in aesthetic perception. Keywords: aesthetic perception, expertise, experimental aesthetics, neuroaesthetics, art appreciation. __________________________________________________________________________________ Soc. What about beautiful and ugly, good and bad? Theat. Yes, these too; in these, above all, I think the soul examines the being they have as compared with one another. Here it seems to be making calculation within itself of past and present in relation to future. Soc. Not so fast, now. Plato, Theaetetus, 186a,b1 Does perception come before knowledge, creating its base, giving it an input, so to speak; or is it already a way of knowing? In the last decades, there has been a strong tendency – in various theories of perception that have arisen after a sense-datum theory was so thoroughly discarded2 – to comply with the latter (although there has been no common theory of what way of knowing it is). -

Toward a Psycho-Historical Framework for the Science of Art Appreciation

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk ProvidedBEHAVIORAL by Lancaster E-Prints AND BRAIN SCIENCES (2013) 36, 123–180 doi:10.1017/S0140525X12000489 The artful mind meets art history: Toward a psycho-historical framework for the science of art appreciation Nicolas J. Bullot ARC Centre of Excellence in Cognition and its Disorders, Department of Cognitive Science, Macquarie University, New South Wales 2109, Australia [email protected] http://www.maccs.mq.edu.au/members/profile.html?memberID=521 Rolf Reber Department of Education, University of Bergen, Postboks 7807, N-5020 Bergen, Norway [email protected] http://www.uib.no/persons/Rolf.Reber#publikasjoner Abstract: Research seeking a scientific foundation for the theory of art appreciation has raised controversies at the intersection of the social and cognitive sciences. Though equally relevant to a scientific inquiry into art appreciation, psychological and historical approaches to art developed independently and lack a common core of theoretical principles. Historicists argue that psychological and brain sciences ignore the fact that artworks are artifacts produced and appreciated in the context of unique historical situations and artistic intentions. After revealing flaws in the psychological approach, we introduce a psycho-historical framework for the science of art appreciation. This framework demonstrates that a science of art appreciation must investigate how appreciators process causal and historical information to classify and explain their psychological responses to art. Expanding on research about the cognition of artifacts, we identify three modes of appreciation: basic exposure to an artwork, the artistic design stance,and artistic understanding. The artistic design stance, a requisite for artistic understanding, is an attitude whereby appreciators develop their sensitivity to art-historical contexts by means of inquiries into the making, authorship, and functions of artworks.