Early Modern Experimental Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Western Philosophy Rev

Designed by John Cornet, Phoenix HS (Ore) Western Philosophy rev. September 2012 The very process of philosophy has been a driving force in the tranformation of the world. From the figure who dwells upon how to achieve power, to the minister who contemplates the paradox of the only truth (their faith) yet which is also stagnent, to the astronomers who are searching the stars for signs of other civilizations, to the revolutionaries who sought to construct a national government which would protect the rights of the minority, the very exercise of philosophy and philosophical thought is at a core of human nature. Philosophy addresses what are sometimes called the "big questions." These include questions of morality and ethics, ideology/faith,, politics, the truth of knowledge, the nature of reality, and the meaning of human existance (...just to name a few!) (Religion addresses some of the same questions, but while philosophy and religion overlap in some questions, they can and do differ significantly in the approach they take to answering them.) Subject Learning Outcomes Skills-Based Learning Outcomes Behavioral Expectations and Grading Policy Develop an appreciation for and enjoyment of Organize, maintain and learn how to study from a learning, particularly in how learning should subject-specific notebook Attendance, participation and cause us to question what we think we know Be able to demonstrate how to take notes (including being prepared are daily and have a willingness to entertain new utilizing two-column format) expectations perspectives on issues. Be able to engage in meaningful, substantive discussion A classroom culture of respect and Students will develop familiarity with major with others. -

May 12, 2017 Department of Philosophy Undergraduate Course Descriptions

UB Spring Session January 30 - May 12, 2017 Department of Philosophy Undergraduate Course Descriptions PHI 101 Introduction to Philosophy K. Cho M, W, F, 9:00 AM-9:50 AM Class # 24095 This is an introductory philosophy course with a compact and yet global design. Instead of the frequently adopted but seldom fully utilized textbooks averaging 630 pates we have chosen a text with only 130 ages but packed with content that is literally “Global”. Text: John Dewey, Confucius and Global Philosophy, by Joseph Grange, 2004, SUNY Press; Plus Occasional Handouts in class. The choice of the two names Dewey and Confucius is more symbolic. Nobody would think these two embody the Western half and The Eastern half of the world; philosophy it is rather in terms of “working connections” they reveal to each other that we perceive them as representatives of our age it its needs. Dewey was certainly a typical American philosopher, who like no one else. Advanced the cause of Pragmatism. But he was also the American philosopher who was the most open to the world. He lectured in Beijing and promoted talented Chinese scholars who came to seek his guidance. And who remembers today that Dewey was thoroughly at home in Kant’s, Kant's Critique and was a skilled Hegelian dialectician? “Breathing is an affair as much as it is an affair of the air”. Or “Walking is an affair of legs as much as it is an affair of the earth.” In these simple words, Dewy translated the speculative language of German Idealism and made philosophy an affair of living. -

1 Forthcoming in Oxford Studies in Experimental Philosophy Causal Reasoning

Forthcoming in Oxford Studies in Experimental Philosophy Causal Reasoning: Philosophy and Experiment* James Woodward History and Philosophy of Science University of Pittsburgh 1. Introduction The past few decades have seen much interesting work, both within and outside philosophy, on causation and allied issues. Some of the philosophy is understood by its practitioners as metaphysics—it asks such questions as what causation “is”, whether there can be causation by absences, and so on. Other work reflects the interests of philosophers in the role that causation and causal reasoning play in science. Still other work, more computational in nature, focuses on problems of causal inference and learning, typically with substantial use of such formal apparatuses as Bayes nets (e.g. , Pearl, 2000, Spirtes et al, 2001) or hierarchical Bayesian models (e.g. Griffiths and Tenenbaum, 2009). All this work – the philosophical and the computational -- might be described as “theoretical” and it often has a strong “normative” component in the sense that it attempts to describe how we ought to learn, reason, and judge about causal relationships. Alongside this normative/theoretical work, there has also been a great deal of empirical work (hereafter Empirical Research on Causation or ERC) which focuses on how various subjects learn causal relationships, reason and judge causally. Much of this work has been carried out by psychologists, but it also includes contributions by primatologists, researchers in animal learning, and neurobiologists, and more rarely, philosophers. In my view, the interactions between these two groups—the normative/theoretical and the empirical -- has been extremely fruitful. In what follows, I describe some ideas about causal reasoning that have emerged from this research, focusing on the “interventionist” ideas that have figured in my own work. -

Experimental Philosophy, Robert Kane, and the Concept of Free Will

Journal of Cognition and Neuroethics Experimental Philosophy, Robert Kane, and the Concept of Free Will J. Neil Otte University at Buffalo, The State University of New York Biography J. Neil Otte is presently in the Ph.D. program at the University at Buffalo (SUNY) and works in moral psychology, cognitive science, and the history of philosophy. For six years, he was an adjunct lecturer in philosophy at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York City. In the last three years, he has been an organizer of the Buffalo Annual Experimental Philosophy Conference, an organizer for a conference on sentiment and reason in early modern philosophy, and has worked as an ontologist for the research foundation, CUBRC. Acknowledgements The author wishes to thank Gunnar Björnsson, Gregg Caruso, and Oisín Deery for their supportive comments and conversation during the Free Will Conference at the Insight Institute of Neurosurgery and Neuroscience in Fall of 2014, as well as conference organizer Jami Anderson. Publication Details Journal of Cognition and Neuroethics (ISSN: 2166-5087). March, 2015. Volume 3, Issue 1. Citation Otte, J. Neil. 2015. “Experimental Philosophy, Robert Kane, and the Concept of Free Will.” Journal of Cognition and Neuroethics 3 (1): 281–296. Experimental Philosophy, Robert Kane, and the Concept of Free Will J. Neil Otte Abstract Trends in experimental philosophy have provided new and compelling results that are cause for re-evaluations in contemporary discussions of free will. In this paper, I argue for one such re-evaluation by criticizing Robert Kane’s well-known views on free will. I argue that Kane’s claims about pre-theoretical intuitions are not supported by empirical findings on two accounts. -

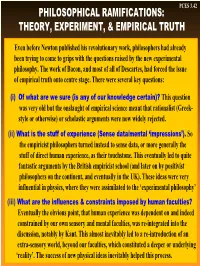

Philosophical Ramifications: Theory, Experiment, & Empirical Truth

PCES 3.42 PHILOSOPHICAL RAMIFICATIONS: THEORY, EXPERIMENT, & EMPIRICAL TRUTH Even before Newton published his revolutionary work, philosophers had already been trying to come to grips with the questions raised by the new experimental philosophy. The work of Bacon, and most of all of Descartes, had forced the issue of empirical truth onto centre stage. There were several key questions: (i) Of what are we sure (is any of our knowledge certain)? This question was very old but the onslaught of empirical science meant that rationalist (Greek- style or otherwise) or scholastic arguments were now widely rejected. (ii) What is the stuff of experience (Sense data/mental ‘impressions’). So the empiricist philosophers turned instead to sense data, or more generally the stuff of direct human experience, as their touchstone. This eventually led to quite fantastic arguments by the British empiricist school (and later on by positivist philosophers on the continent, and eventually in the UK). These ideas were very influential in physics, where they were assimilated to the ‘experimental philosophy’ (iii) What are the influences & constraints imposed by human faculties? Eventually the obvious point, that human experience was dependent on and indeed constrained by our own sensory and mental faculties, was re-integrated into the discussion, notably by Kant. This almost inevitably led to a re-introduction of an extra-sensory world, beyond our faculties, which constituted a deeper or underlying ‘reality’. The success of new physical ideas inevitably helped this process. PCES 3.43 BRITISH EMPIRICISM I: Locke & “Sensations” Locke was the first British philosopher of note after Bacon; his work is a reaction to the European rationalists, and continues to elaborate ‘experimental philosophy’. -

HURON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE Philosophy 2202G: Early Modern Philosophy 2017-2018

HURON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE Philosophy 2202G: Early Modern Philosophy 2017-2018 Winter Term, 2018 Instructor: Dr. Steve Bland Prerequisites: none Office: A304 Tuesdays, 10:30-12:30pm, V207 Office hours: Thursdays, 12:30-2:30pm Thursdays, 11:30-12:30pm, V207 Email: [email protected] The Early Modern period (ca. 1600-1800) was one of the most fruitful and exciting eras in the history of philosophy and science. New methods of inquiry and theories of the universe and the mind marked a radical shift away from medieval philosophy and towards a novel philosophical landscape of ideas. This course will provide an introductory survey of the philosophical theories of some of the most well known and influential thinkers of the Early Modern age, including: Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz, Locke, Berkeley, and Hume. In reading and discussing some of the classic primary works of these philosophers, we will become engaged in the following topics: scepticism, the nature of reality and the mind, the existence of god, free will, and personal identity. More generally, this course will focus on the crucially important rationalism- empiricism debate, which concerned not only the source of knowledge, but the proper method of answering philosophical questions. In other words, we will canvass Early Modern philosophical theories in an effort to answer the question: how should philosophy be done? COURSE LEARNING OBJECTIVES On successful completion of this course, students will be able to: 1. Clearly formulate and explain the central philosophical theories discussed in this course. 2. Reformulate complex arguments found within primary sources. 3. Defend a plausible position on the question of the origins of philosophical knowledge. -

CVII: 2 (February 2000), Pp

TAMAR SZABÓ GENDLER July 2014 Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences · Yale University · P.O. Box 208365 · New Haven, CT 06520-8365 E-mail: [email protected] · Office telephone: 203.432.4444 ACADEMIC EMPLOYMENT 2006- Yale University Academic Vincent J. Scully Professor of Philosophy (F2012-present) Professor of Philosophy (F2006-F2012); Professor of Psychology (F2009-present); Professor of Humanities (S2007-present); Professor of Cognitive Science (F2006-present) Administrative Dean, Faculty of Arts and Sciences (Sum2014-present) Deputy Provost, Humanities and Initiatives (F2013-Sum2014) Chair, Department of Philosophy (Sum2010-Sum2013) Chair, Cognitive Science Program (F2006-Sum2010) 2003-2006 Cornell University Academic Associate Professor of Philosophy (with tenure) (F2003-S2006) Administrative Director of Graduate Studies, Department of Philosophy (F2004-S2006) Co-Director, Program in Cognitive Studies (F2004-S2006) 1997-2003 Syracuse University Academic Associate Professor of Philosophy (with tenure) (F2002-S2003) Assistant Professor of Philosophy (tenure-track) (F1999-S2002) Allen and Anita Sutton Distinguished Faculty Fellow (F1997-S1999) Administrative Director of Undergraduate Studies, Department of Philosophy (F2001-S2003) 1996-1997 Yale University Academic Lecturer (F1996-S1997) EDUCATION 1990-1996 Harvard University. PhD (Philosophy), August 1996. Dissertation title: ‘Imaginary Exceptions: On the Powers and Limits of Thought Experiment’ Advisors: Robert Nozick, Derek Parfit, Hilary Putnam 1989-1990 University of California -

Experimental Philosophy Jordan Kiper, Stephen Stich, H. Clark Barrett

Experimental Philosophy Jordan Kiper, Stephen Stich, H. Clark Barrett, & Edouard Machery Kiper, J., Stich, S., Barrett, H.C., & Machery, E. (in press). Experimental philosophy. In D. Ludwig, I. Koskinen, Z. Mncube, L. Poliseli, & L. Reyes-Garcia (Eds.), Global Epistemologies and Philosophies of Science. New York, NY: Routledge. Acknowledgments: This publication was made possible through the support of a grant from the John Templeton Foundation. The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the John Templeton Foundation. Abstract Philosophers have argued that some philosophical concepts are universal, but it is increasingly clear that the question of philosophical universals is far from settled, and that far more cross- cultural research is necessary. In this chapter, we illustrate the relevance of investigating philosophical concepts and describe results from recent cross-cultural studies in experimental philosophy. We focus on the concept of knowledge and outline an ongoing project, the Geography of Philosophy Project, which empirically investigates the concepts of knowledge, understanding, and wisdom across cultures, languages, religions, and socioeconomic groups. We outline questions for future research on philosophical concepts across cultures, with an aim towards resolving questions about universals and variation in philosophical concepts. 1 Introduction For centuries, thinkers have urged that fundamental philosophical concepts, such as the concepts of knowledge or right and wrong, are universal or at least shared by all rational people (e.g., Plato 1892/375 BCE; Kant, 1998/1781; Foot, 2003). Yet many social scientists, in particular cultural anthropologists (e.g., Boas, 1940), but also continental philosophers such as Foucault (1969) have remained skeptical of these claims. -

“Modern” Philosophy: Introduction

“Modern” Philosophy: Introduction [from Debates in Modern Philosophy by Stewart Duncan and Antonia LoLordo (Routledge, 2013)] This course discusses the views of various European of his contemporaries (e.g. Thomas Hobbes) did see philosophers of the seventeenth century. Along with themselves as engaged in a new project in philosophy the thinkers of the eighteenth century, they are con- and the sciences, which somehow contained a new sidered “modern” philosophers. That might not seem way of explaining how the world worked. So, what terribly modern. René Descartes was writing in the was this new project? And what, if anything, did all 1630s and 1640s, and Immanuel Kant died in 1804. these modern philosophers have in common? By many standards, that was a long time ago. So, why is the work of Descartes, Kant, and their contempor- Two themes emerge when you read what Des- aries called modern philosophy? cartes and Hobbes say about their new philosophies. First, they think that earlier philosophers, particu- In one way this question has a trivial answer. larly so-called Scholastic Aristotelians—medieval “Modern” is being used here to describe a period of European philosophers who were influenced by time, and to contrast it with other periods of time. So, Aristotle—were mistaken about many issues, and modern philosophy is not the philosophy of today as that the new, modern way is better. (They say nicer contrasted with the philosophy of the 2020s or even things about Aristotle himself, and about some other the 1950s. Rather it’s the philosophy of the 1600s previous philosophers.) This view was shared by and onwards, as opposed to ancient and medieval many modern philosophers, but not all of them. -

CURRICULUM VITAE January, 2018 DANIEL GARBER

CURRICULUM VITAE January, 2018 DANIEL GARBER Position: A. Watson Armour III University Professor of Philosophy Address: Department of Philosophy 1879 Hall Princeton University Princeton, NJ 08544-1006 Address (September 2017-July 2018) Institut d’études avancées 17, quai d’Anjou 75004 Paris France Telephone: 609-258-4307 (voice) 609-258-1502 (FAX) 609-258-4289 (Departmental office) Email: [email protected] Erdös number: 16 EDUCATIONAL RECORD Harvard University, 1967-1975 A.B. in Philosophy, 197l A.M. in Philosophy, 1974 Ph.D. in Philosophy, 1975 TEACHING EXPERIENCE Princeton University 2002- Professor of Philosophy and Associated Faculty, Program in the History of Science 2005-12 Chair, Department of Philosophy 2008-09 Old Dominion Professor 2009- Associated Faculty, Department of Politics 2009-16 Stuart Professor of Philosophy Garber -2- 2016- A. Watson Armour III University Professor of Philosophy University of Chicago 1995-2002 Lawrence Kimpton Distinguished Service Professor in Philosophy, the Committee on Conceptual and Historical Studies of Science, the Morris Fishbein Center for Study of History of Science and Medicine and the College 1986-2002 Professor 1982-86 Associate Professor (with tenure) 1975-82 Assistant Professor 1998-2002 Chairman, Committee on Conceptual and Historical Studies of Science (formerly Conceptual Foundations of Science) 2001 Acting Chairman, Department of Philosophy 1995-98 Associate Provost for Education and Research 1994-95 Chairman, Conceptual Foundations of Science 1987-94 Chairman, Department of Philosophy Harvard College 1972-75 Teaching Assistant and Tutor University of Minnesota, Spring 1979, Visiting Assistant Professor of Philosophy Johns Hopkins University, 1980-1981, Visiting Assistant Professor of Philosophy Princeton University 1982-1983 Visiting Associate Professor of Philosophy Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton, 1985-1986, Member École Normale Supérieure (Lettres) (Lyon, France), November 2000, Professeur invitée. -

1 Joshua Knobe Yale University Take a Few Courses in Cognitive Science

FREE WILL AND THE SCIENTIFIC VISION1 Joshua Knobe Yale University [Forthcoming in Edouard Machery and Elizabeth O’Neill (eds.), Current Controversies in Experimental Philosophy. RoutledGe.] Take a few courses in cognitive science, and you are likely to come across a certain kind of metaphor for the workinGs of the human mind. The metaphor Goes like this: Consider a piece of computer software. The software consists of a collection of states and processes. We can predict what the software will do by lookinG at the complex ways in which these states and processes interact. The human mind works in more or less the same way. It too is just a complex collection of states and processes, and we can predict what a human being will do by thinking about the complex ways in which these states and processes interact. One can imaGine someone sayinG: ‘I see all these states and processes, but aren’t you forgetting somethinG further – namely, the person herself?’ This question, however, is a foolish one. It is no more helpful than it would be to say: ‘I see all these states and processes, but where is the software itself?’ The software just is a collection of states and processes, and the human mind is the same sort of thinG. This metaphor does a Good job of capturinG the basic approach one finds throuGhout the sciences of the mind. We miGht say that it captures the scientific vision of how the human mind works. But one could also imaGine another, very different metaphor for the workinGs of the mind. -

2202F: Early Modern Philosophy

THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO DEPARTMENT OF PHILOSOPHY Undergraduate Course Outline Philosophy 2202F: Early Modern Philosophy Fall 2019 Instructor: Prof. Corey W. Dyck MWF 12:30-1:30 StH 4138, Office Hours: MW 1:30-2:30 Classroom: SSC 2036 661-2111 x85749 [email protected] DESCRIPTION The early Modern period (roughly 1600-1800) was an intellectually rich and immensely influential chapter in the history of philosophy. In this course, we will survey some of its key figures and ideas, including Descartes, Spinoza, Leibniz, Locke, Berkeley, and Hume, with special attention to topics in metaphysics and epistemology. We will also consider a number of contributions by marginalized thinkers in the period. TEXT Modern Philosophy: An Anthology of Primary Sources Ariew and Watkins, eds. (3rd ed. Hackett Publishing) OBJECTIVES Students completing this course successfully will: (1) be familiar with some of the principal themes and arguments of the philosophers of the early Modern period, as well as a number of minor and marginalized figures; (2) have demonstrated an ability to comprehend and reflect upon complex philosophical arguments; (3) be able to write a longer argumentative essay exhibiting writing, researching, and critical skills. REQUIREMENTS Assignment Due Date Value Study Question Responses in-class on Fridays 15% Mid-Term TBD 20% Term Paper (Multi-stage assignment) 25% Final Exam TBD 40% Study Question Responses Most weeks, you will be provided with 4-5 study questions designed to focus your attention to key points in the reading and lectures. During the last class of the week, you will provide a brief written response to one of the questions (of my choosing).