CHAPTER 1 5 ABDA and ANZA CN the Second World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SEMAPHORE SEA POWER CENTRE - AUSTRALIA ISSUE 4, 2012 SHIPS NAMED CANBERRA in the Annals of the Royal Australian Navy (RAN), Two of 25 January 1929

SEMAPHORE SEA POWER CENTRE - AUSTRALIA ISSUE 4, 2012 SHIPS NAMED CANBERRA In the annals of the Royal Australian Navy (RAN), two of 25 January 1929. She then ‘showed the flag’ at Bunbury, its warships have proudly carried the name of Australia’s Albany, Adelaide and Melbourne, finally arriving in her capital city – Canberra. On 17 February 2011, a third ship, home port of Sydney on 16 February. In each port large the first of two new amphibious ships (LHD) built for the crowds gathered to see the RAN’s latest cruiser with its RAN, was launched in Spain. She is currently forecast to impressive main armament of eight, 8-inch guns. enter service in 2014 following her official commissioning as HMAS Canberra (III). With this in mind, it is timely to For the next ten years Canberra operated on the review the history of the Canberras, examine their Australian Station. Together with Australia she shared the contribution to Australian maritime security and highlight role of flagship of the RAN Squadron and the two formed the unique bonds forged between these ships and the the backbone of the RAN during the lean years of the citizens of our nation’s land-locked capital. Great Depression. At that time Canberra made only occasional overseas visits to the nearby Dutch East The name Canberra is derived from the language of the Indies, New Caledonia and Fiji. Ngunnawal people who traditionally occupied the district now recognised as the Australian Capital Territory (ACT). Following the outbreak of hostilities with Nazi Germany in The word means a ‘meeting place’ of either rivers, or of September 1939, Canberra began her wartime career tribes joining together to feast on Bogong moths in conducting patrols and escort duties in home waters mountains to the south of the region. -

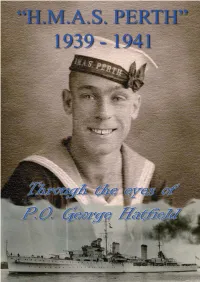

37845R CS3 Book Hatfield's Diaries.Indd

“H.M.A.S. PERTH” 1939 -1941 From the diaries of P.O. George Hatfield Published in Sydney Australia in 2009 Publishing layout and Cover Design by George Hatfield Jnr. Printed by Springwood Printing Co. Faulconbridge NSW 2776 1 2 Foreword Of all the ships that have flown the ensign of the Royal Australian Navy, there has never been one quite like the first HMAS Perth, a cruiser of the Second World War. In her short life of just less than three years as an Australian warship she sailed all the world’s great oceans, from the icy wastes of the North Atlantic to the steamy heat of the Indian Ocean and the far blue horizons of the Pacific. She survived a hurricane in the Caribbean and months of Italian and German bombing in the Mediterranean. One bomb hit her and nearly sank her. She fought the Italians at the Battle of Matapan in March, 1941, which was the last great fleet action of the British Royal Navy, and she was present in June that year off Syria when the three Australian services - Army, RAN and RAAF - fought together for the first time. Eventually, she was sunk in a heroic battle against an overwhelming Japanese force in the Java Sea off Indonesia in 1942. Fast and powerful and modern for her times, Perth was a light cruiser of some 7,000 tonnes, with a main armament of eight 6- inch guns, and a top speed of about 34 knots. She had a crew of about 650 men, give or take, most of them young men in their twenties. -

RAN Ships Lost

CALL THE HANDS OCCASIONAL PAPER 6 Issue No. 6 March 2017 Royal Australian Navy Ships Honour Roll Given the 75th anniversary commemoration events taking place around Australia and overseas in 2017 to honour ships lost in the RAN’s darkest year, 1942 it is timely to reproduce the full list of Royal Australian Navy vessels lost since 1914. The table below was prepared by the Directorate of Strategic and Historical Studies in the RAN’s Sea Power Centre, Canberra lists 31 vessels lost along with a total of 1,736 lives. Vessel (* Denotes Date sunk Casualties Location Comments NAP/CPB ship taken up (Ships lost from trade. Only with ships appearing casualties on the Navy Lists highlighted) as commissioned vessels are included.) HMA Submarine 14-Sep-14 35 Vicinity of Disappeared following a patrol near AE1 Blanche Bay, Cape Gazelle, New Guinea. Thought New Guinea to have struck a coral reef near the mouth of Blanche Bay while submerged. HMA Submarine 30-Apr-15 0 Sea of Scuttled after action against Turkish AE2 Marmara, torpedo boat. All crew became POWs, Turkey four died in captivity. Wreck located in June 1998. HMAS Goorangai* 20-Nov-40 24 Port Phillip Collided with MV Duntroon. No Bay survivors. HMAS Waterhen 30-Jun-41 0 Off Sollum, Damaged by German aircraft 29 June Egypt 1941. Sank early the next morning. HMAS Sydney (II) 19-Nov-41 645 207 km from Sunk with all hands following action Steep Point against HSK Kormoran. Located 16- WA, Indian Mar-08. Ocean HMAS Parramatta 27-Nov-41 138 Approximately Sunk by German submarine. -

Ordinary Council Information Bulletin November 2019

COUNCIL INFORMATION BULLETIN November 2019 November 2019 Council Information Bulletin PAGE 2 City of Rockingham Council Information Bulletin November 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS Planning and Development Services Bulletin 11 1. Health Services 11 1. Health Services Team Overview 11 2. Human Resource Update 11 3. Project Status Reports 11 3.1 FoodSafe 11 3.2 Industrial and Commercial Waste Monitoring 11 3.3 Mosquito Control Program 12 3.4 Environmental Waters Sampling 13 3.5 Food Sampling 14 4. Information Items 14 4.1 Food Recalls 14 4.2 Food Premises Inspections 14 4.3 Public Building Inspections 15 4.4 Outdoor Event Approvals 15 4.5 Permit Approvals 16 4.6 Complaint - Information 17 4.7 Noise Complaints – Detailed Information 17 4.8 Health Approvals 17 4.9 Septic Tank Applications 18 4.10 Demolitions 18 4.11 Swimming Pool and Drinking Water Samples 18 4.12 Rabbit Processing 18 4.13 Hairdressing and Skin Penetration Premises 18 2. Building Services 19 1. Building Services Team Overview 19 2. Human Resource Update 19 3. Project Status Reports 19 4. Information Items 19 4.1 Monthly Building Permit Approvals - (All Building Types) 19 4.2 Other Permits 20 4.3 Monthly Caravan Park Site Approvals 20 3. Compliance and Emergency Liaison 21 1. Compliance and Emergency Liaison Team Overview 21 2. Human Resource Update 21 3. Project Status Reports 21 3.1 Refurbishment of the New Compliance Services Building 21 4. Information Items 22 4.1 Ranger Services Action Reports 22 4.2 Pet Registration Drive Project 23 4.3 Building and Development Compliance 23 4.4 Land Use - Planning Enforcement 24 November 2019 Council Information Bulletin PAGE 3 City of Rockingham Council Information Bulletin November 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS 4.5 Emergency Management and Fire Prevention 26 4.6 CRM - October 2019 26 4.7 Fire Management Plans 26 4.8 Fire Control Notice 26 4.9 Firebreak Inspections 26 4.10 Fire and Rescue Service Urban Bushland Plans 26 4.11 SmartWatch Key Result Areas 26 4. -

Leadership, Devotion to Duty, Self Sacrifice

SEMAPHORE SEA POWER CENTRE - AUSTRALIA ISSUE 3, 2017 LEADERSHIP, DEVOTION TO DUTY, SELF SACRIFCE – HMAS YARRA IN ACTION 1942 “We were taken on deck and shown, as they tried to become supportive of Germany and there was concern impress us, the might of the Japanese Navy. The Yarra that Nazi forces, which had recently invaded Russia, was the only ship left and we could see flames and a would drive southwards to the Persian Gulf. great deal of smoke. The two destroyers were circling Yarra took part in the subjugation of Iran on 25 August Yarra which appeared stationary and were pouring fire sinking the Iranian sloop Babr, at her berth at into her. She was still firing back as we could see the odd Khorramshahr, with No. 2 gun, under the control of Acting gun flashes. The three cruisers then formed a line ahead Leading Seaman Ronald ‘Buck’ Taylor, the first to open and steamed away from the scene. The last we saw of fire. Yarra also captured two Iranian gunboats by boarding Yarra was a high column of smoke - but we were all party. The leaders of the boarding parties; Petty Officer vividly impressed by her fight.”1 Cook Norman Fraser, Petty Officer Steward Robert The first six months of the Pacific campaign were the Hoskins and Stoker Petty Officer Donald Neal were each darkest days in the history of Australia and her Navy. On awarded a Distinguished Service Medal. Harrington was 15 February 1942 the Malayan campaign ended with the awarded a Distinguished Service Order.3 fall of Singapore and over 15,000 Australian Service The sloop remained in the Persian Gulf and Arabian Sea personnel became Prisoners of War. -

INFANTRYMAN August 2015

INFANTRYMAN The Journal of the RAR Association SA August 2015 Keeping the Spirit Alive ANZAC Centenary Memorial Garden Walk project a long hard trek any of you would be aware of ANZAC MCentenary Memorial Garden Walk project which, to the best of our knowledge, has been on the wish list drawing board for about nine years. Not wishing to bore you with the detailed financial arrangements however it is a joint effort by A distinguished 7RAR Association marching on ANZAC the Federal and State Governments, the Adelaide City Day. For those less observant notice they are all dressed Council and Government House. This, as you can in collar, tie and coats out of respect for their lost mates imagine, has taken an enormous amount of time and and the occasion. effort to finally pull together where all stakeholders is like a goat track. The old green tin fence containing including veterans have been consulted and some basic the Government House grounds looks like the back of design elements taking shape. a warehouse. The view to the Torrens and the Parade Ground is fragmented. Overall much will be done through The walk will start at the National War Memorial on North this project to improve the aesthetics and feel of the Terrace and finish at the end where the current footpath whole of the Kintore Avenue and the eastern boundary of approaches the Avenue of Honour and Torrens Parade Government House. Ground. The Governor of South Australia, His Excellency the Honorable Hieu Van Le AO, has relinquished 10 It is proposed that only the three services and theatres of metres of the eastern gardens abutting Kintore Avenue war will be incorporated with the lovely old Dardanelles for the project. -

03 Chapters 4-7 Burns

76 CHAPTER 4 THE REALITY BEHIND THE BRISBANE LINE ALLEGATIONS Curtin lacked expertise in defence matters. He did not understand the duties or responsibilities of military commanders and never attended Chiefs of Staff meetings, choosing to rely chiefly on the Governments public service advisers. Thus Shedden established himself as Curtins chief defence adviser. Under Curtin his influence was far greater than 1 it had ever been in Menzies day. Curtins lack of understanding of the role of military commanders, shared by Forde, created misunderstandings and brought about refusal to give political direction. These factors contributed to events that underlay the Brisbane Line controversy. Necessarily, Curtin had as his main purpose the fighting and the winning of the war. Some Labor politicians however saw no reason why the conduct of the war should prevent Labor introducing social reforms. Many, because of their anti-conscriptionist beliefs, were unsympathetic 2 to military needs. Conversely, the Army Staff Corps were mistrustful of their new masters. The most influential of their critics was Eddie Ward, the new Minister for Labour and National Service. His hatred of Menzies, distrust of the conservative parties, and suspicion of the military impelled him towards endangering national security during the course of the Brisbane Line controversy. But this lay in the future in the early days of the Curtin Government. Not a great deal changed immediately under Curtin. A report to Forde by Mackay on 27 October indicated that appreciations and planning for local defence in Queensland and New South Wales were based on the assumption that the vital area of Newcastle-Sydney-Port Kembla had priority in defence. -

February 2010 VOL

Registered by AUSTRALIA POST NO. PP607128/00001 THE February 2010 VOL. 33 No.1 The official journal of The ReTuRNed & ServiceS League OF austraLia POSTAGE PAID SURFACE ListeningListeningWa Branch incorporated • PO Box 3023 adelaide Tce, Perth 6832 • est. 1920 PostPostAUSTRALIA MAIL Toodyay Remembered RSL gratefully acknowledges the financial support from the Veteran Community and the Aged Fund. Australia Day Legal How I Readers Awards Loopholes Lost Weight Satisfactory Page Page Page Survey 15 Legal Loopholes 21 22 Page 28 Rick Hart - Proudly supporting your local RSL Belmont 9373 4400 COUNTRY STORES BunBury SuperStore 9722 6200 AlBAny - kitcHen & LaunDrY onLY 9842 1855 CIty meGAStore 9227 4100 Broome 9192 3399 ClAremont 9284 3699 BunBury SuperStore 9722 6200 JoondAlup SuperStore 9301 4833 kAtAnnInG 9821 1577 mAndurAh SuperStore 9586 4700 Country CAllerS FreeCAll 1800 654 599 mIdlAnd SuperStore 9267 9700 o’Connor SuperStore 9337 7822 oSBorne pArk SuperStore 9445 5000 VIC pArk - Park Discount suPerstore 9470 4949 RSL Members receive special pricing. “We won’t be beaten on price. I put my name on it.”* Just show your membership card! 2 The ListeNiNg Post February 2010 Delivering Complete Satisfaction Northside 14 Berriman drive, wangara phone: 6400 0950 09 Micra 5 door iT’S A great movE automatic TiidA ST • Powerful 1.4L engine sedan or • 4 sp automatic hatch • DOHC • Air conditioning • Power steering • CD player # # • ABS Brakes • Dual Front Airbags $15,715 $16,490 • 6 Speed Manual # dRiveaway# Applicable to TPI card holders only. Manual. Metallic colours $395 extra dRiveaway Applicable to TPI card holders only. Manual. Metallic colours $395 extra movE into A dualiS NAvara turbO diesel ThE all new RX 4X4 dualiS st LiMited stock # # • ABS Brakes • Dual Airbags • CD Player • Dual SRS Airbags , $35,490 • 3000kg Towing Capacity $24860 • Air Conditioning # dRiveaway# Applicable to TPI card holders only. -

Publisher's Note

Adam Matthew Publications is an imprint of Adam Matthew Digital Ltd, Pelham House, London Road, Marlborough, Wiltshire, SN8 2AG, ENGLAND Telephone: +44 (1672) 511921 Fax: +44 (1672) 511663 Email: [email protected] POPULAR NEWSPAPERS DURING WORLD WAR II Parts 1 to 5: 1939-1945 (The Daily Express, The Mirror, The News of The World, The People and The Sunday Express) Publisher's Note This microfilm publication makes available complete runs the Daily Express, The Daily Mirror, the News of the World, The People, and the Sunday Express for the years 1939 through to 1945. The project is organised in five parts and covers the newspapers in chronological sequence. Part 1 provides full coverage for 1939; Part 2: 1940; Part 3: 1941; Part 4: 1942-1943; and finally, Part 5 covers 1944-1945. At last social historians and students of journalism can consult complete war-time runs of Britain’s popular newspapers in their libraries. Less august than the papers of record, it is these papers which reveal most about the impact of the war on the home front, the way in which people amused themselves in the face of adversity, and the way in which public morale was kept high through a mixture of propaganda and judicious reporting. Most importantly, it is through these papers that we can see how most ordinary people received news of the war. For, with a combined circulation of over 23 million by 1948, and a secondary readership far in excess of these figures, the News of the World, The People, the Daily Express, The Daily Mirror, and the Sunday Express reached into the homes of the majority of the British public and played a critical role in shaping public perceptions of the war. -

Pearl Harbor Revisited: U.S

United States Cryptologic History Cryptologic States United United States Cryptologic History Pearl Harbor Revisited: U.S. Navy Communications Intelligence 1924–1941 Pearl Harbor Revisited Harbor Pearl 2013 Series IV: World War II | Volume 6 n57370 Center for Cryptologic History This publication presents a historical perspective for informational and educational purposes, is the result of independent research, and does not necessarily reflect a position of NSA/CSS or any other U.S. government entity. This publication is distributed free by the National Security Agency. If you would like additional copies, please submit your request to: Center for Cryptologic History National Security Agency 9800 Savage Road, Suite 6886 Fort George G. Meade, MD 20755 Frederick D. Parker retired from NSA in 1984 after thirty-two years of service. Following his retirement, he worked as a reemployed annuitant and volunteer in the Center for Cryptologic His- tory. Mr. Parker served in the U.S. Marine Corps from 1943 to 1945 and from 1950 to 1952. He holds a B.S. from the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service. Cover: First Army photo of the bombing of Hawaii, 7 December 1941; the battleship USS Arizona in background is on fire and sinking. Signal Corps photo taken from Aeia Heights. Pearl Harbor Revisited: U.S. Navy Communications Intelligence 1924–1941 Frederick D. Parker Series IV: World War II | Volume 6 Third edition 2013 Contents Foreword ...................................................................... 5 Introduction ................................................................. -

History of the Royal Marines 1837-1914 HE Blumberg

History of the Royal Marines 1837-1914 HE Blumberg (Minor editing by Alastair Donald) In preparing this Record I have consulted, wherever possible, the original reports, Battalion War and other Diaries, accounts in Globe and Laurel, etc. The War Office Official Accounts, where extant, the London Gazettes, and Orders in Council have been taken as the basis of events recounted, and I have made free use of the standard histories, eg History of the British Army (Fortescue), History of the Navy (Laird Clowes), Britain's Sea Soldiers (Field), etc. Also the Lives of Admirals and Generals bearing on the campaigns. The authorities consulted have been quoted for each campaign, in order that those desirous of making a fuller study can do so. I have made no pretence of writing a history or making comments, but I have tried to place on record all facts which can show the development of the Corps through the Nineteenth and early part of the Twentieth Centuries. H E BLUMBERG Devonport January, 1934 1 P A R T I 1837 – 1839 The Long Peace On 20 June, 1837, Her Majesty Queen Victoria ascended the Throne and commenced the long reign which was to bring such glory and honour to England, but the year found the fortunes of the Corps at a very low ebb. The numbers voted were 9007, but the RM Artillery had officially ceased to exist - a School of Laboratory and nominally two companies quartered at Fort Cumberland as part of the Portsmouth Division only being maintained. The Portsmouth Division were still in the old inadequate Clarence Barracks in the High Street; Plymouth and Chatham were in their present barracks, which had not then been enlarged to their present size, and Woolwich were in the western part of the Royal Artillery Barracks. -

INDO 20 0 1107105566 1 57.Pdf (5.476Mb)

J f < r Pahang Channel ....... ,Ci' p p ' rw \ * 0 xv# t‘ p'r; Ua/ S' f - \jg , f t ’ 1 1 « « * 1 * « f 1 * *, M m v t 1 * * * a g % * * *«ii f»i i 1 1 1 n > fc 1 1 ? ' Old Channel Western Channel Eastern Channel Old Channel Map 1 LANDFALL ON THE PALEMBANG COAST IN MEDIEVAL TIMES O. W. Wolters The Palembang Coast during the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Centuries I had always supposed that the metropolitan centers of Srivijaya, though probably dispersed according to their royal, social, commercial, or food-supplying functions, were in the neighborhood o f modern Palem bang city. I was among those influenced by the presence there of seventh century inscriptions, and I also assumed that the area where Bukit Seguntang stood had long ago possessed relig iou s prestige among Malays and contributed to the fame of the Palembang area. I did not believe that the capital of Srivijaya had always been in the Palembang area. Palembang enjoyed this status from the seventh century until the second half of the eleventh, when the Malay overlord*s center was moved to the Jambi area where it remained until turbulent events in the second half of the fourteenth century set in train the foundation of the Malay maritime empire of Malacca by a Palembang prince. After the shift in political hegemony from Palembang to Jambi, perhaps only officials in the Chinese court anachronistically continued to use the expression "San-fo-ch*iM ("Srivijaya") to identify the prominent polit ica l center on the southeastern coast of Sumatra.