Pine Nuts: a Review of Recent Sanitary Conditions and Market Development

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calophyllum Inophyllum L

Calophyllum inophyllum L. Guttiferae poon, beach calophyllum LOCAL NAMES Bengali (sultanachampa,punnang,kathchampa); Burmese (ph’ông,ponnyet); English (oil nut tree,beauty leaf,Borneo mahogany,dilo oil tree,alexandrian laurel); Filipino (bitaog,palo maria); Hindi (surpunka,pinnai,undi,surpan,sultanachampa,polanga); Javanese (njamplung); Malay (bentagor bunga,penaga pudek,pegana laut); Sanskrit (punnaga,nagachampa); Sinhala (domba); Swahili (mtondoo,mtomondo); Tamil (punnai,punnagam,pinnay); Thai (saraphee neen,naowakan,krathing); Trade name (poon,beach calophyllum); Vietnamese (c[aa]y m[uf]u) Calophyllum inophyllum leaves and fruit (Zhou Guangyi) BOTANIC DESCRIPTION Calophyllum inophyllum is a medium-sized tree up to 25 m tall, sometimes as large as 35 m, with sticky latex either clear or opaque and white, cream or yellow; bole usually twisted or leaning, up to 150 cm in diameter, without buttresses. Outer bark often with characteristic diamond to boat- shaped fissures becoming confluent with age, smooth, often with a yellowish or ochre tint, inner bark usually thick, soft, firm, fibrous and laminated, pink to red, darkening to brownish on exposure. Crown evenly conical to narrowly hemispherical; twigs 4-angled and rounded, with plump terminal buds 4-9 mm long. Shade tree in park (Rafael T. Cadiz) Leaves elliptical, thick, smooth and polished, ovate, obovate or oblong (min. 5.5) 8-20 (max. 23) cm long, rounded to cuneate at base, rounded, retuse or subacute at apex with latex canals that are usually less prominent; stipules absent. Inflorescence axillary, racemose, usually unbranched but occasionally with 3-flowered branches, 5-15 (max. 30)-flowered. Flowers usually bisexual but sometimes functionally unisexual, sweetly scented, with perianth of 8 (max. -

The Miracle Resource Eco-Link

Since 1989 Eco-Link Linking Social, Economic, and Ecological Issues The Miracle Resource Volume 14, Number 1 In the children’s book “The Giving Tree” by Shel Silverstein the main character is shown to beneÞ t in several ways from the generosity of one tree. The tree is a source of recreation, commodities, and solace. In this parable of giving, one is impressed by the wealth that a simple tree has to offer people: shade, food, lumber, comfort. And if we look beyond the wealth of a single tree to the benefits that we derive from entire forests one cannot help but be impressed by the bounty unmatched by any other natural resource in the world. That’s why trees are called the miracle resource. The forest is a factory where trees manufacture wood using energy from the sun, water and nutrients from the soil, and carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. In healthy growing forests, trees produce pure oxygen for us to breathe. Forests also provide clean air and water, wildlife habitat, and recreation opportunities to renew our spirits. Forests, trees, and wood have always been essential to civilization. In ancient Mesopotamia (now Iraq), the value of wood was equal to that of precious gems, stones, and metals. In Mycenaean Greece, wood was used to feed the great bronze furnaces that forged Greek culture. Rome’s monetary system was based on silver which required huge quantities of wood to convert ore into metal. For thousands of years, wood has been used for weapons and ships of war. Nations rose and fell based on their use and misuse of the forest resource. -

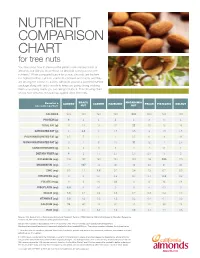

Nutrient Comparison Chart

NUTRIENT COMPARISON CHART for tree nuts You may know how to measure the perfect one-ounce portion of almonds, but did you know those 23 almonds come packed with nutrients? When compared ounce for ounce, almonds are the tree nut highest in fiber, calcium, vitamin E, riboflavin and niacin, and they are among the lowest in calories. Almonds provide a powerful nutrient package along with tasty crunch to keep you going strong, making them a satisfying snack you can feel good about. The following chart shows how almonds measure up against other tree nuts. BRAZIL MACADAMIA Based on a ALMOND CASHEW HAZELNUT PECAN PISTACHIO WALNUT one-ounce portion1 NUT NUT CALORIES 1602 190 160 180 200 200 160 190 PROTEIN (g) 6 4 4 4 2 3 6 4 TOTAL FAT (g) 14 19 13 17 22 20 13 19 SATURATED FAT (g) 1 4.5 3 1.5 3.5 2 1.5 1.5 POLYUNSATURATED FAT (g) 3.5 7 2 2 0.5 6 4 13 MONOUNSATURATED FAT (g) 9 7 8 13 17 12 7 2.5 CARBOHYDRATES (g) 6 3 9 5 4 4 8 4 DIETARY FIBER (g) 4 2 1.5 2.5 2.5 2.5 3 2 POTASSIUM (mg) 208 187 160 193 103 116 285 125 MAGNESIUM (mg) 77 107 74 46 33 34 31 45 ZINC (mg) 0.9 1.2 1.6 0.7 0.4 1.3 0.7 0.9 VITAMIN B6 (mg) 0 0 0.1 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.3 0.2 FOLATE (mcg) 12 6 20 32 3 6 14 28 RIBOFLAVIN (mg) 0.3 0 0.1 0 0 0 0.1 0 NIACIN (mg) 1.0 0.1 0.4 0.5 0.7 0.3 0.4 0.3 VITAMIN E (mg) 7.3 1.6 0.3 4.3 0.2 0.4 0.7 0.2 CALCIUM (mg) 76 45 13 32 20 20 30 28 IRON (mg) 1.1 0.7 1.7 1.3 0.8 0.7 1.1 0.8 Source: U.S. -

Tree Nut Allergy

TREE NUT ALLERGY Tree nut allergy is one of the most common food allergies in children and adults, and can cause a severe, potentially fatal allergic reaction (anaphylaxis). Tree nuts include, but are not limited to: almond, Brazil nut, cashew, hazelnut, macadamia, pecan, pine nut, pistachio and walnut. These are not to be confused or grouped together with peanut, which is a legume, or seeds, such as sunflower or sesame. What is a food allergy? test results with the information given Severe Symptoms or Anaphylaxis in your medical history for a diagnosis. Food allergy is a serious medical These tests may include: LUNG: Shortness of breath, condition affecting up to 32 million wheezing, repetitive cough people in the United States, including ● Skin prick test 1 in 13 children. Food allergy happens ● Blood test HEART: Pale or bluish skin, when your body’s immune defenses ● Oral food challenge faintness, weak pulse, dizziness that normally fight disease attack a ● Trial elimination diet food protein instead. The food protein THROAT: Tight or hoarse throat, is called an allergen, and your body’s Oral food challenges are considered the trouble breathing or swallowing response is called an allergic reaction. gold standard for definitive diagnosis. MOUTH: Significant swelling of the How common are nut allergies? Depending on your medical history and tongue or lips initial test results, you may need to take Nine foods account for a majority of more than one test before receiving your SKIN: Many hives over body, reactions: milk, eggs, peanuts, tree nuts, diagnosis. widespread redness soy, wheat, fish, sesame and shellfish. -

UNECE Standard for Pine Nuts (DDP-12)

UNECE STANDARD DDP-12 concerning the marketing and commercial quality control of PINE NUT KERNELS 2013 EDITION UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 2013 NOTE Working Party on Agricultural Quality Standards Working Party on Agricultural Quality Standards The commercial quality standards developed by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) Working Party on Agricultural Quality Standards help facilitate international trade, encourage high-quality production, improve profitability and protect consumer interests. UNECE standards are used by Governments, producers, traders, importers and exporters, and other international organizations. They cover a wide range of agricultural products, including fresh fruit and vegetables, dry and dried produce, seed potatoes, meat, cut flowers, eggs and egg products. Any member of the United Nations can participate, on an equal footing, in the activities of the Working Party. For more information on agricultural standards, please visit our website http://www.unece.org/trade/agr/welcome.html. The new Standard for Pine Nut Kernels is based on document ECE/TRADE/C/WP.7/2013/31, reviewed and adopted by the Working Party at its sixty-ninth session. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations Secretariat concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Mention of company -

Various Terminologies Associated with Areca Nut and Tobacco Chewing: a Review

Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology Vol. 19 Issue 1 Jan ‑ Apr 2015 69 REVIEW ARTICLE Various terminologies associated with areca nut and tobacco chewing: A review Kalpana A Patidar, Rajkumar Parwani, Sangeeta P Wanjari, Atul P Patidar Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, Modern Dental College and Research Center, Indore, Madhya Pradesh, India Address for correspondence: ABSTRACT Dr. Kalpana A Patidar, Globally, arecanut and tobacco are among the most common addictions. Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, Tobacco and arecanut alone or in combination are practiced in different regions Modern Dental College and Research Centre, in various forms. Subsequently, oral mucosal lesions also show marked Airport Road, Gandhi Nagar, Indore ‑ 452 001, Madhya Pradesh, India. variations in their clinical as well as histopathological appearance. However, it E‑mail: [email protected] has been found that there is no uniformity and awareness while reporting these habits. Various terminologies used by investigators like ‘betel chewing’,‘betel Received: 26‑02‑2014 quid chewing’,‘betel nut chewing’,‘betel nut habit’,‘tobacco chewing’and ‘paan Accepted: 28‑03‑2015 chewing’ clearly indicate that there is lack of knowledge and lots of confusion about the exact terminology and content of the habit. If the health promotion initiatives are to be considered, a thorough knowledge of composition and way of practicing the habit is essential. In this article we reviewed composition and various terminologies associated with areca nut and tobacco habits in an effort to clearly delineate various habits. Key words: Areca nut, habit, paan, quid, tobacco INTRODUCTION Tobacco plant, probably cultivated by man about 1,000 years back have now crept into each and every part of world. -

Pharmaceutical Applications of a Pinyon Oleoresin;

PHARMAC E UT I CAL A PPL ICAT IONS OF A PINYON OLEORESIN by VICTOR H. DUKE A thesis submitted to the faculty of the University of Utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Pharmacognosy College of Pharmacy University of Utah May, 1961 LIBRARY UNIVERSITY elF UTAH I I This Thesis for the Ph. D. degree by Victor H. Duke has been approved by Reader, Supervisory Head, Major Department iii Acknowledgements The author wishes to acknowledge his gratitude to each of the following: To Dr. L. David Hiner, his Dean, counselor, and friend, who suggested the problem and encouraged its completion. To Dr. Ewart A. Swinyard, critical advisor and respected teacher, for inspiring his original interest in pharmacology. To Dr. Irving B. McNulty and Dr. Robert K. Vickery, true gentlemen of the botanical world, for patiently intro ducing him to its wonders. To Dr. Robert V. Peterson, an amiable faculty con sultant, for his unstinting assistance. To his wife, Shirley and to his children, who have worked with him, worried with him, and who now have succeeded with him. i v TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. REPORTED USES OF PINYON OLEORESI N 6 A. Internal Uses 6 B. External Uses 9 III. GENUS PINUS 1 3 A. Introduction 13 B. Pinyon Pines 14 1. Pinus edulis Engelm 18 2. Pinus monophylla Torr. and Frem. 23 3. Anatomy 27 (a) Leaves 27 (b) Bark 27 (c) Wood 30 IV. COLLECTION OF THE OLEORESIN 36 A. Ch ip Method 40 B. -

Virtually Bringing the Nut & Dried Fruit Sector Together

Edition 81. Nº 3 November 2020 INC ONLINE CONFERENCE Virtually Bringing the Nut & Dried Fruit Sector Together p. 57 www.nutfruit.org November 2020 | NUTFRUIT November 2020 | NUTFRUIT Edition 81. Nº 3 November 2020 The INC is the international umbrella organization for the nut and dried fruit industry and the source for information on health, nutrition, statistics, food safety, and international standards and regulations regarding nuts and dried fruits. BOARD OF TRUSTEES Michael Waring - Chairman Business News 9 INC Congress 54 MWT Foods, Australia Ashok Krishen - 1st Vice Chairman 9 Partnership Besana-Importaco 54 Dubai, INC XXXIX World Nut and Dried Olam International Limited, Singapore Fruit Congress Pino Calcagni - 2nd Vice Chairman 10 PepsiCo Targets 100% Renewable Besana Group, Italy Electricity Globally Riccardo Calcagni Besana Group, Italy 11 Danone’s Alpro Celebrates 40 Years INC News 57 Bill Carriere Carriere Family Farms, USA 12 Creamy, Crunchy, Chewy: Introducing 57 INC Online Conference Karsten Dankert Nature Valley Packed, a New Sustained Max Kiene GmbH, Germany Energy Bar 60 INC Academia: The Best Training Program in Roby Danon the Nut and Dried Fruit Industry Voicevale Ltd, UK Cao Derong 62 INC Webinars China Chamber of Commerce, China Gourmet 14 Joan Fortuny Borges Agricultural & Industrial Nuts (BAIN), Spain 63 Trend Research: International Market Giles Hacking 14 Carme Ruscalleda, Barcelona, Spain Opportunities CG Hacking & Sons Limited, UK Mike Hohmann 64 Real Power for Real People: Boost your The Wonderful Company, -

'Whole Nut' Processing of Coconut

All ACP Agriculture Commodities Programme AAACP Pacific Brief No. 5 October 2011 ‘Whole nut’ processing of coconut – opportunities and challenges for the Pacific region Key messages • Reorienting coconut industries to produce multiple high-value products (‘whole nut’ processing) has the potential to stimulate economic growth in the Pacific region. • Some high-value products can be made at the village level, directly addressing rural poverty. • A new initiative aims to develop pilot multipurpose processing centres in six countries, to demonstrate technical and commercial viability of ‘whole nut’ processing. • Success will depend on support from governments, the private sector, and regional research and development organisations. Compared to other parts of the world, notably tropical ‘Whole nut’ processing – i.e. processing the different Asia, coconut-based industries in the Pacific region parts of the coconut to produce multiple high-value are stagnating. Pacific island countries have mostly products – has the potential to revitalise coconut failed to invest in new developments, and copra and industries in the region. If opportunities can be low-quality coconut oil continue to be the main created at the village level, and viable market chains products. Low global prices for these commodities developed for products, this will also contribute to create little incentive for producers, and failure to reducing rural poverty. replant coconut palms has led to an overall picture of senile trees and declining production. Coconuts are currently mostly processed into copra and low-grade coconut oil. Photo: Richard Markham 1 | AAACP PACIFIC BRIEF No. 5 The ‘whole-nut’ concept • Changes the focus of coconut industries to higher value products • By multipurpose processing, maximises the returns on each coconut Products and markets With the focus on copra and coconut oil, the parts of the coconut that are currently going to waste are the husks, shells and coconut water. -

Naval Stores Review and Journal of Trade

NAVAL STORES REVIEW AND JOURNAL OF TRADE A Weekly Paper for Naval Stores Producers, Factors, Exporters, Dealers, and Manufacturers of Soaps, Varnishes, Paper, Printing Inks, Etc. VOL. XXIV, No. 23. SAVANNAH, GA., Saturday, September 5, 1914. Price, $5.00 Per Annum W. D. KRENSON. H. D. WEED : J. A. Gd. CARSON, President. J. D. WEED & CO.. H.L.KAYTON, 1st Vice-President. J. A. G. CARSON, Jr., 2nd Vice=President W. L. McDOWELL, 3d Vice-President H. F. E. SCHUSTER, Secretary Savannah, Georgia. W. A. CHRISTIAN, Treasurer. Wholesale Hardware Cason Naval Stores Railroad Spikes. Bar Band and Hoop Iron, ...Factors and Wholesale Grocers... Turpentine Tools, Ete. ORGANIZED IN 1879. OLDEST HOUSE IN THE BUSINESS. Principal Office, SAVANNAH, GEORGIA, National Bank Building. OHHH MA Branch Office, JACKSONVILLE, FLORIDA, OHO a Atlantic National Bank Building. NIV £1) OHHH 1 With an organization unsurpassed and ample means at our 0) 301340 command, our facilities for handling your business are HHH TTVAVN ALS second to none. SONINNAC ‘dL .... WE INVITE YOUR CORRESPONDENCE.... HH “ J pure ‘V100VSNId CHE terrier trstropesbotentestesbstrrteofesetente frosted |B INEST OH UOIISBISIIBS ‘V1 ‘XQ TYAUN 1U6PISOIJ-00TA CHESNUTT & O'NEILL, 0) ITVSITOHM SSIPUBYDIII Ino HH NAVAL STORES FACTORS, A HoNvao HOH S3HOLS -00T HH SUPPLIES. daddies Suosjed 20140 HO UI ‘NOXIAT'V'H SIH0LS JUOPISOIJ sjuawilsedsap Ship your naval stores to mus at MIN OHH Savannah, the Leading Market of the Yjoq World, and thus aid in keeping up HHH SHIOOYUD ‘DM Competition and maintaining High HH [BARN deeds Prices. ‘SNVITHO £3,008 HHO PUB V1 HOH ‘HEHLVE $31031S * Send Us Your Orders at Savannah, Georgia. -

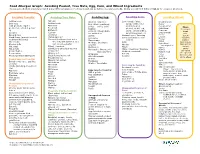

Avoiding Peanut, Tree Nuts, Egg, Corn, and Wheat Ingredients Common Food Allergens May Be Listed Many Different Ways on Food Labels and Can Be Hidden in Common Foods

Food Allergen Graph: Avoiding Peanut, Tree Nuts, Egg, Corn, and Wheat Ingredients Common food allergens may be listed many different ways on food labels and can be hidden in common foods. Below you will find different labels for common allergens. Avoiding Peanuts: Avoiding Tree Nuts: Avoiding Egg: Avoiding Corn: Avoiding Wheat: Artificial nuts Almond Albumin / albumen Corn - meal, flakes, Bread Crumbs Beer nuts Artificial nuts Egg (dried, powdered, syrup, solids, flour, Bulgur Cold pressed, expeller Brazil nut solids, white, yolk) niblets, kernel, Cereal extract Flour: pressed or extruded peanut Beechnut Eggnog alcohol, on the cob, Club Wheat all-purpose Butternut oil Globulin / Ovoglobulin starch, bread,muffins Conscous bread Goobers Cashew Fat subtitutes sugar/sweetener, oil, Cracker meal cake Durum Ground nuts Chestnut Livetin Caramel corn / flavoring durum Einkorn Mandelonas (peanuts soaked Chinquapin nut Lysozyme Citric acid (may be corn enriched Emmer in almond flavoring) Coconut (really is a fruit not a based) graham Mayonnaise Farina Mixed nuts tree nut, but classified as a Grits high gluten Meringue (meringue Hydrolyzed Monkey nuts nut on some charts) high protein powder) Hominy wheat protein Nut meat Filbert / hazelnut instant Ovalbumin Maize Kamut Gianduja -a chocolate-nut mix pastry Nut pieces Ovomucin / Ovomucoid / Malto / Dextrose / Dextrate Matzoh Peanut butter Ginkgo nut Modified cornstarch self-rising Ovotransferrin Matzoh meal steel ground Peanut flour Hickory nut Polenta Simplesse Pasta stone ground Peanut protein hydrolysate -

Breadfruit Production Guide

BREADFRUIT PRODUCTION RECOMMENDED PRACTICES GUIDE FOR GROWING, HARVESTING, AND HANDLING 2nd Edition By Craig Elevitch, Diane Ragone, and Ian Cole Breadfruit Production Guide: Recommended Acknowledgments practices for growing, harvesting, and handling We are indebted to the many reviewers of this work, who con- tributed numerous corrections and suggestions that shaped By Craig Elevitch, Diane Ragone, and Ian Cole the final publication: Failautusi Avegalio, Jr., Heidi Bornhorst, © 2013, 2014 Craig Elevitch, Diane Ragone, and Ian Cole. All John Cadman, Jesus Castro, Jim Currie, Andrea Dean, Emih- Rights Reserved. Second Edition 2014. ner Johnson, Shirley Kauhaihao, Robert Paull, Grant Percival, the Pacific Breadfruit Project (Andrew McGregor, Livai Tora, Photographs are copyright their respective owners. Kyle Stice, and Kaitu Erasito), and the Scientific Research Or- ISBN: 978-1939618030 ganisation of Samoa (Tilafono David Hunter, Kenneth Wong, Gaufa Salesa Fetu, Kuinimeri Asora Finau). The authors grate- This is a publication of Ho‘oulu ka ‘Ulu—Revitalizing fully acknowledge Andrea Dean for input in formulating the Breadfruit, a project of Hawai‘i Homegrown Food Network content of this guide. Photo contributions by Jim Wiseman, Ric and Breadfruit Institute of the National Tropical Botanical Rocker, and Kamaui Aiona, are greatly appreciated. The kapa Garden. The Ho‘oulu ka ‘Ulu project is directed by Andrea ‘ulu artwork pictured on cover was crafted by Kumu Wesley Sen. Dean, Craig Elevitch, and Diane Ragone. Finally, our deepest gratitude to all of the Pacific Island farmers Recommended citation who have contributed to the knowledge base for breadfruit for generations. Elevitch, C., D. Ragone, and I. Cole. 2014. Breadfruit Produc- tion Guide: Recommended practices for growing, harvest- Author bios ing, and handling (2nd Edition).