Breadfruit Production Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Calophyllum Inophyllum L

Calophyllum inophyllum L. Guttiferae poon, beach calophyllum LOCAL NAMES Bengali (sultanachampa,punnang,kathchampa); Burmese (ph’ông,ponnyet); English (oil nut tree,beauty leaf,Borneo mahogany,dilo oil tree,alexandrian laurel); Filipino (bitaog,palo maria); Hindi (surpunka,pinnai,undi,surpan,sultanachampa,polanga); Javanese (njamplung); Malay (bentagor bunga,penaga pudek,pegana laut); Sanskrit (punnaga,nagachampa); Sinhala (domba); Swahili (mtondoo,mtomondo); Tamil (punnai,punnagam,pinnay); Thai (saraphee neen,naowakan,krathing); Trade name (poon,beach calophyllum); Vietnamese (c[aa]y m[uf]u) Calophyllum inophyllum leaves and fruit (Zhou Guangyi) BOTANIC DESCRIPTION Calophyllum inophyllum is a medium-sized tree up to 25 m tall, sometimes as large as 35 m, with sticky latex either clear or opaque and white, cream or yellow; bole usually twisted or leaning, up to 150 cm in diameter, without buttresses. Outer bark often with characteristic diamond to boat- shaped fissures becoming confluent with age, smooth, often with a yellowish or ochre tint, inner bark usually thick, soft, firm, fibrous and laminated, pink to red, darkening to brownish on exposure. Crown evenly conical to narrowly hemispherical; twigs 4-angled and rounded, with plump terminal buds 4-9 mm long. Shade tree in park (Rafael T. Cadiz) Leaves elliptical, thick, smooth and polished, ovate, obovate or oblong (min. 5.5) 8-20 (max. 23) cm long, rounded to cuneate at base, rounded, retuse or subacute at apex with latex canals that are usually less prominent; stipules absent. Inflorescence axillary, racemose, usually unbranched but occasionally with 3-flowered branches, 5-15 (max. 30)-flowered. Flowers usually bisexual but sometimes functionally unisexual, sweetly scented, with perianth of 8 (max. -

Producing Fruit Trees for Home

Tree Fruits NC COOPERATIVE EXTENSION FORSYTH COUNTY CENTER 1450 Fairchild Road Winston-Salem NC 27105 Phone: 336-703-2850 Website: www.forsyth.cc/ces 1 Producing Tree Fruit for Home Use AG-28 Growing tree fruit in the home garden or yard can be a rewarding pastime. However, careful planning, preparation, and care of the trees are essential for success. This publication tells you what to consider before planting, how to plant your trees, and how to take care of them to ensure many seasons of enjoyment. Part 1: Planning Before Planting Fruit Selection Selecting the type of fruit to grow is the first step in tree fruit production. To begin, you need to know which tree fruit can be grown in North Carolina. Your region's climate determines the type of fruit you can grow successfully. The climate must be compatible with the growing requirements of the selected fruit crop. To take an extreme example, a tropical fruit such as the banana simply cannot survive in North Carolina. Bananas require a warmer climate and a longer growing season. Other tree fruit that may look promising in the glossy pages of mail order catalogs are also destined to fail if grown in incompatible climates. Climatic conditions vary greatly from one region to another in North Carolina, so make sure that the fruit you choose can grow successfully in your area. Table 1. Potential Tree Fruit Crops for North Carolina Fruit Location Varietal Considerations Management Most varieties will grow in North Apples Throughout North Carolina Moderate Carolina. Plant fire blight-resistant varieties Asian Pears Throughout North Carolina Moderate only. -

The Miracle Resource Eco-Link

Since 1989 Eco-Link Linking Social, Economic, and Ecological Issues The Miracle Resource Volume 14, Number 1 In the children’s book “The Giving Tree” by Shel Silverstein the main character is shown to beneÞ t in several ways from the generosity of one tree. The tree is a source of recreation, commodities, and solace. In this parable of giving, one is impressed by the wealth that a simple tree has to offer people: shade, food, lumber, comfort. And if we look beyond the wealth of a single tree to the benefits that we derive from entire forests one cannot help but be impressed by the bounty unmatched by any other natural resource in the world. That’s why trees are called the miracle resource. The forest is a factory where trees manufacture wood using energy from the sun, water and nutrients from the soil, and carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. In healthy growing forests, trees produce pure oxygen for us to breathe. Forests also provide clean air and water, wildlife habitat, and recreation opportunities to renew our spirits. Forests, trees, and wood have always been essential to civilization. In ancient Mesopotamia (now Iraq), the value of wood was equal to that of precious gems, stones, and metals. In Mycenaean Greece, wood was used to feed the great bronze furnaces that forged Greek culture. Rome’s monetary system was based on silver which required huge quantities of wood to convert ore into metal. For thousands of years, wood has been used for weapons and ships of war. Nations rose and fell based on their use and misuse of the forest resource. -

Sassafras Tea: Using a Traditional Method of Preparation to Reduce the Carcinogenic Compound Safrole Kate Cummings Clemson University, [email protected]

Clemson University TigerPrints All Theses Theses 5-2012 Sassafras Tea: Using a Traditional Method of Preparation to Reduce the Carcinogenic Compound Safrole Kate Cummings Clemson University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses Part of the Forest Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Cummings, Kate, "Sassafras Tea: Using a Traditional Method of Preparation to Reduce the Carcinogenic Compound Safrole" (2012). All Theses. 1345. https://tigerprints.clemson.edu/all_theses/1345 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses at TigerPrints. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Theses by an authorized administrator of TigerPrints. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SASSAFRAS TEA: USING A TRADITIONAL METHOD OF PREPARATION TO REDUCE THE CARCINOGENIC COMPOUND SAFROLE A Thesis Presented to the Graduate School of Clemson University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Forest Resources by Kate Cummings May 2012 Accepted by: Patricia Layton, Ph.D., Committee Chair Karen C. Hall, Ph.D Feng Chen, Ph. D. Christina Wells, Ph. D. ABSTRACT The purpose of this research is to quantify the carcinogenic compound safrole in the traditional preparation method of making sassafras tea from the root of Sassafras albidum. The traditional method investigated was typical of preparation by members of the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians and other Appalachian peoples. Sassafras is a tree common to the eastern coast of the United States, especially in the mountainous regions. Historically and continuing until today, roots of the tree are used to prepare fragrant teas and syrups. -

Tea Seed Oil and Health Properties Fatih Seyis1, Emine

Tea Seed Oil and Health Properties Fatih Seyis1, Emine Yurteri1, Aysel Özcan1 1Recep Tayyip Erdoğan University: Faculty of Agriculture and Natural Science, Field Crops Department, Rize/Turkey, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: Tea Oil has a mild fragrant flavor that goes with anything. It’s not a heavy oil like Olive Oil, but thinner – more like almond oil. If the taste or “oiliness” of olive oil overpowers your food. Along with its mild taste and pleasant tea-like aroma, this oil touts impressive health benefits. Tea seed oil has a high smoke point, contains more monounsaturated fatty acids than olive oil, contains fewer saturated fatty acids than olive oil, contains high levels of Vitamin E, polyphenol antioxidants and both Omegas 3 and 6, but has less Omega 6 and Polyunsaturated Fats than olive oil. Health Benefits of tea seed oil are: it can be applied topically and consumed internally to obtain its health benefits, camellia oil can be used for skin, hair, has anti-cancer effects, effects boost immunity and reduces oxidative stress. Camellia oil is used for a variety of other purposes, for example for cooking, as machinery lubricant, as ingredient in beauty products like night creams, salves, in hair care products and perfumes and is used to coat iron products to prevent rusting. Key words: Tea, seed oil, health 1. Introduction Like other genera of Camellia (from Theaceae family), the tea plant (C.sinensis) produces large oily seeds. In some countries where tea seed oil is abundantly available, it has been accepted as edible oil (Sahari et al., 2004). -

Taro Improvement and Development in Papua New Guinea

Taro Improvement and Development in Papua New Guinea - A Success Story Abner Yalu1, Davinder Singh1#, Shyam Singh Yadav1 1National Agricultural Research Institute, Lae, PNG Corresponding author email: [email protected] 2Current address: CIMMYT, Nairobi, Kenya [email protected] Asia-Pacific Association of Agricultural Research Institutions c/o FAO Regional Office for Asia and the Pacific Bangkok, Thailand For copies and further information, please write to: The Executive Secretary Asia-Pacific Association of Agricultural Research Institutions (APAARI) C/o FAO Regional Office for Asia & the Pacific (FAO RAP) Maliwan Mansion, 39 Phra Atit Road Bangkok 10200, Thailand Tel : (+66 2) 697 4371 – 3 Fax : (+66 2) 697 4408 E-Mail : [email protected] Printed in August 2009 Foreword Taro (Colocasia esculenta) is a crop of prime economic importance, used as a major food in the Pacific Island Countries (PICs). In Papua New Guinea (PNG), taro is consumed by the majority of people whose livelihood is mainly dependent on subsistence agriculture. It is the second most important root staple crop after sweet potato in terms of consumption, and is ranked fourth root crop after sweet potato, yam and cassava in terms of production. PNG is currently ranked fourth highest taro producing nation in the world. This success story illustrates as to how National Agricultural Research Institute (NARI) of PNG in collaboration with national, regional and international partners implemented a south Pacific regional project on taro conservation and utilization (TaroGen), and how the threat of taro leaf blight disease was successfully addressed by properly utilizing national capacity. So far, four high yielding leaf blight resistant taro varieties have been released to the farmers, which are widely adopted now. -

Maafala Fact Sheet

MA‘AFALA This popular breadfruit variety originated in Samoa and Tonga and has been grown in Hawai‘i for decades. Ma‘afala is a fast-growing tree that tends to be shorter, with a more compact shape than most breadfruit varieties. Trees can begin bearing fruit in 2-1/2 to 3 years. 16-month-old tree 36-month-old tree Season in Hawai‘i 100 Ma‘afala ‘Ulu 0 Jan Feb Mar Apr May June July Aug Sept Oct Nov Dec Average seasonality profile of Ma‘afala compared to the Hawaiian ‘Ulu. BREADFRUIT INSTITUTE - NATIONAL TROPICAL BOTANICAL GARDEN 3530 Papalina Road, Kalaheo, Kauai, Hawaii 96741 Phone: 808.332.7324 ext 221 Fax: 808.332.9765 www.ntbg.org/breadfruit MA‘AFALA Weight 1.4 - 2.3 lbs (634-1053 g) 1.7 lbs (783g) average Shape & Size Oval; 5-6“ long x 4-5“ wide Edible Portion 83% Protein Ma’afala ‘Ulu Taro White Rice Potato g/100 g 0 1 2 3 4 5 Fiber Ma’afala ‘Ulu Taro White Rice Potato g/100 g 0 2 4 6 8 10 Potassium Ma’afala ‘Ulu Taro White Rice Potato mg/100 g Ma‘afala produces 150-200, or more, 0 250 500 750 1000 1250 delicious, nutritious fruits per year. The fruit has a creamy to pale yellow flesh and is Calcium usually seedless. The flesh has a soft, tender Ma’afala texture when cooked. ‘Ulu Breadfruit is a starchy energy-rich Taro White Rice carbohydrate food and is also gluten free. Potato mg/100 g Ma‘afala is higher in protein (3.3%) than 0 20 40 60 80 100 most breadfruit varieties, and flour made from the dried fruit contains 7.6% protein. -

Chemical Constituents from Flueggea Virosa and the Structural Revision of Dehydrochebulic Acid Trimethyl Ester

molecules Article Chemical Constituents from Flueggea virosa and the Structural Revision of Dehydrochebulic Acid Trimethyl Ester Chih-Hua Chao 1,2,*, Ying-Ju Lin 3,4, Ju-Chien Cheng 5, Hui-Chi Huang 6, Yung-Ju Yeh 5, Tian-Shung Wu 7,8, Syh-Yuan Hwang 9 and Yang-Chang Wu 1,2,10,11,* 1 School of Pharmacy, China Medical University, Taichung 40402, Taiwan 2 Chinese Medicine Research and Development Center, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung 40447, Taiwan 3 School of Chinese Medicine, China Medical University, Taichung 40402, Taiwan; [email protected] 4 Genetic Center, Department of Medical Research, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung 40447, Taiwan 5 Department of Medical Laboratory Science and Biotechnology, China Medical University, Taichung 40402, Taiwan; [email protected] (J.-C.C.); [email protected] (Y.-J.Y.) 6 Department of Chinese Pharmaceutical Sciences and Chinese Medicine Resources, China Medical University, Taichung 40402, Taiwan; [email protected] 7 Department of Pharmacy, National Cheng Kung University, Tainan 70101, Taiwan; [email protected] 8 Department of Pharmacy and Graduate Institute of Pharmaceutical Technology, Tajen University, Pingtung 90741, Taiwan 9 Endemic Species Research Institute, Council of Agriculture, Nantou 55244, Taiwan; [email protected] 10 Center for Molecular Medicine, China Medical University Hospital, Taichung 40447, Taiwan 11 Graduate Institute of Natural Products, Kaohsiung Medical University, Kaohsiung 80708, Taiwan * Correspondence: [email protected] (C.-H.C.); [email protected] (Y.-C.W.); Tel.: +886-4-2205-3366 (ext. 5157) (C.-H.C.) Academic Editor: Derek J. McPhee Received: 9 August 2016; Accepted: 12 September 2016; Published: 16 September 2016 Abstract: In an attempt to study the chemical constituents from the twigs and leaves of Flueggea virosa, a new terpenoid, 9(10!20)-abeo-ent-podocarpane, 3β,10α-dihydroxy-12-methoxy-13- methyl-9(10!20)-abeo-ent-podocarpa-6,8,11,13-tetraene (1), as well as five known compounds were characterized. -

Olive Oil Jars Left Behind By

live oil jars left behind by the ancient Greeks are testament to our centuries- old use of cooking oil. Along with salt and pepper, oil Oremains one of the most important and versatile tools in your kitchen. It keeps food from sticking to pans, adds flavor and moisture, and conducts the heat that turns a humble stick of potato into a glorious french fry. Like butter and other fats, cooking oil also acts as a powerful solvent, unleashing fat-soluble nutrients and flavor compounds in everything from tomatoes and onions to spices and herbs. It’s why so many strike recipes begin with heating garlic in oil rather than, say, simmering it in water. The ancient Greeks didn’t tap many cooking oils. (Let’s see: olive oil, olive oil, or—ooh, this is exciting!—how about olive oil?) But you certainly can. From canola to safflower to grapeseed to walnut, each oil has its own unique flavor (or lack thereof), aroma, and optimal cooking temperature. Choosing the right kind for the task at hand can save you money, boost your health, and improve your cooking. OK, so you probably don’t stop to consider your cooking oil very often. But there’s a surprising amount to learn about What’s this? this liquid gold. BY VIRGINIAWILLIS Pumpkin seed oil suspended in corn oil—it looks like a homemade Lava Lamp! 84 allrecipes.com PHOTOS BY KATE SEARS WHERE TO store CANOLA OIL GRAPESEED OIL are more likely to exhibit the characteristic YOUR OIL flavor and aroma of their base nut or seed. -

Reliable Fruit Tree Varieties for Santa Cruz County

for the Gardener Reliable Fruit Tree Varieties for Santa Cruz County lanting a fruit tree is, or at least should be, a considered act involving a well thought-out plan. In a sense, you “design” a tree, or by extension, an orchard—and as tempting as it may be to grab a shovel and start digging, the Plast thing you do is plant the tree. There are many elements to the plan for successful deciduous fruit tree growing. They include, but are not limited to – • Site selection • Sanitation, particularly on the orchard floor • Soil—assessment and improvement • Weed management • Scale and diversity of the planting • Pruning/training systems • What genera and species (apple, pear, plum, • Thinning peach, etc.) and what varieties grow well in an area • Pest and disease control • Pollination • Sourcing quality trees • Irrigation • The planting hole and process • A fertility plan and associated fertilizers • Harvest and post-harvest All of the above factors comprise the jigsaw puzzle or the Rubik’s Cube of fruit growing. In essence, you must align all the colored cubes to induce smiles on the faces of both growers and consumers. This article focuses on the selection of genera, species, and varieties that do well in Santa Cruz County, and discusses chill hour requirements as one major criterion for successful fruit tree growing. THE RELIABLE—AND NOT SO RELIABLE What Grows Well Here By “what grows well,” I mean what produces a reliable annual crop and is relatively disease and pest free. In Santa Cruz County, that includes— • Apples • Pluots • Pears -

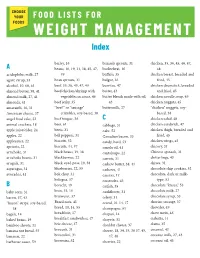

WEIGHT MANAGEMENT Index

CHOOSE YOUR FOOD LISTS FOR FOODS WEIGHT MANAGEMENT Index barley, 16 brussels sprouts, 31 chicken, 35, 36, 45, 46, 47, A beans, 10, 19, 31, 38, 45, 47, buckwheat, 16 48 acidophilus milk, 27 49 buffalo, 35 chicken breast, breaded and agave syrup, 53 bean sprouts, 31 bulgur, 16 fried, 45 alcohol, 10, 60, 61 beef, 35, 36, 45, 47, 49 burritos, 47 chicken drumstick, breaded almond butter, 38, 41 beef/chicken/shrimp with butter, 43 and fried, 45 almond milk, 27, 41 vegetables in sauce, 46 butter blends made with oil, chicken noodle soup, 49 almonds, 41 beef jerky, 35 43 chicken nuggets, 45 amaranth, 16, 31 “beef” or “sausage” buttermilk, 27 “chicken” nuggets, soy- American cheese, 37 crumbles, soy-based, 38 based, 38 angel food cake, 52 beef tongue, 36 C chicken salad, 48 animal crackers, 18 beer, 61 cabbage, 31 chicken sandwich, 47 apple juice/cider, 24 beets, 31 cake, 52 chicken thigh, breaded and apples, 22 bell peppers, 31 Canadian bacon, 35 fried, 45 applesauce, 22 biscotti, 52 candy, hard, 53 chicken wings, 45 apricots, 22 biscuits, 14, 47 canola oil, 41 chicory, 31 artichoke, 31 black beans, 19, 38 cantaloupe, 22 Chinese spinach, 31 artichoke hearts, 31 blackberries, 22 carrots, 31 chitterlings, 43 arugula, 31 black-eyed peas, 19, 38 cashew butter, 38, 41 chives, 31 asparagus, 31 blueberries, 22, 55 cashews, 41 chocolate chip cookies, 52 avocados, 41 bok choy, 31 cassava, 17 chocolate, dark or milk- bologna, 37 casseroles, 45 type, 53 B borscht, 49 catfish, 35 chocolate “kisses,” 53 baby corn, 31 bran, 15, 16 cauliflower, 31 chocolate -

Various Terminologies Associated with Areca Nut and Tobacco Chewing: a Review

Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology Vol. 19 Issue 1 Jan ‑ Apr 2015 69 REVIEW ARTICLE Various terminologies associated with areca nut and tobacco chewing: A review Kalpana A Patidar, Rajkumar Parwani, Sangeeta P Wanjari, Atul P Patidar Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, Modern Dental College and Research Center, Indore, Madhya Pradesh, India Address for correspondence: ABSTRACT Dr. Kalpana A Patidar, Globally, arecanut and tobacco are among the most common addictions. Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology, Tobacco and arecanut alone or in combination are practiced in different regions Modern Dental College and Research Centre, in various forms. Subsequently, oral mucosal lesions also show marked Airport Road, Gandhi Nagar, Indore ‑ 452 001, Madhya Pradesh, India. variations in their clinical as well as histopathological appearance. However, it E‑mail: [email protected] has been found that there is no uniformity and awareness while reporting these habits. Various terminologies used by investigators like ‘betel chewing’,‘betel Received: 26‑02‑2014 quid chewing’,‘betel nut chewing’,‘betel nut habit’,‘tobacco chewing’and ‘paan Accepted: 28‑03‑2015 chewing’ clearly indicate that there is lack of knowledge and lots of confusion about the exact terminology and content of the habit. If the health promotion initiatives are to be considered, a thorough knowledge of composition and way of practicing the habit is essential. In this article we reviewed composition and various terminologies associated with areca nut and tobacco habits in an effort to clearly delineate various habits. Key words: Areca nut, habit, paan, quid, tobacco INTRODUCTION Tobacco plant, probably cultivated by man about 1,000 years back have now crept into each and every part of world.