Pharmaceutical Applications of a Pinyon Oleoresin;

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tree Nut Allergy

TREE NUT ALLERGY Tree nut allergy is one of the most common food allergies in children and adults, and can cause a severe, potentially fatal allergic reaction (anaphylaxis). Tree nuts include, but are not limited to: almond, Brazil nut, cashew, hazelnut, macadamia, pecan, pine nut, pistachio and walnut. These are not to be confused or grouped together with peanut, which is a legume, or seeds, such as sunflower or sesame. What is a food allergy? test results with the information given Severe Symptoms or Anaphylaxis in your medical history for a diagnosis. Food allergy is a serious medical These tests may include: LUNG: Shortness of breath, condition affecting up to 32 million wheezing, repetitive cough people in the United States, including ● Skin prick test 1 in 13 children. Food allergy happens ● Blood test HEART: Pale or bluish skin, when your body’s immune defenses ● Oral food challenge faintness, weak pulse, dizziness that normally fight disease attack a ● Trial elimination diet food protein instead. The food protein THROAT: Tight or hoarse throat, is called an allergen, and your body’s Oral food challenges are considered the trouble breathing or swallowing response is called an allergic reaction. gold standard for definitive diagnosis. MOUTH: Significant swelling of the How common are nut allergies? Depending on your medical history and tongue or lips initial test results, you may need to take Nine foods account for a majority of more than one test before receiving your SKIN: Many hives over body, reactions: milk, eggs, peanuts, tree nuts, diagnosis. widespread redness soy, wheat, fish, sesame and shellfish. -

MF3246 Drought-Tolerant Trees for South-Central Kansas

Drought-Tolerant Trees for South-Central Kansas Jason Griffin, Ph.D., Nursery and Landscape Specialist Steps to establish a drought-tolerant tree Drought is a common occurence affecting the health of trees in south-central Kansas. Property owners who notice • Choose a healthy tree from a retail garden center. A healthy wilting and scorched leaves (below) may wonder if trees tree with a robust root system will establish rapidly, reducing will survive. Drought alone rarely kills well-established transplant shock and stress. To learn more, see Selecting and trees. But effects of extended drought, combined with other Planting a Tree (L870). stressors, can be serious and irreversible. Lack of water • Locate a suitable planting site. Ensure adequate soil volume limits a tree’s ability to absorb nutrients, weakens natural for the selected species. This allows the root system to spread defenses and leaves it vulnerable to heat, cold, insects, and and improves access to soil, water, nutrients, and oxygen. The pathogens. In some cases, the tree may die. root zone should contain fertile, well-drained soil free of pests, diseases, and foreign debris. Avoid any location that collects or All trees have natural protection from ordinary seasonal holds water for a long time. This deprives roots of oxygen, and drought, and some species are known for their ability to reduces root growth and overall plant health. withstand severe, prolonged drought conditions. Even for • Plant properly and at the right time of year. Many tree trees that are not particularly drought-tolerant, a healthy failures can be traced to poor planting practices. -

UNECE Standard for Pine Nuts (DDP-12)

UNECE STANDARD DDP-12 concerning the marketing and commercial quality control of PINE NUT KERNELS 2013 EDITION UNITED NATIONS New York and Geneva, 2013 NOTE Working Party on Agricultural Quality Standards Working Party on Agricultural Quality Standards The commercial quality standards developed by the United Nations Economic Commission for Europe (UNECE) Working Party on Agricultural Quality Standards help facilitate international trade, encourage high-quality production, improve profitability and protect consumer interests. UNECE standards are used by Governments, producers, traders, importers and exporters, and other international organizations. They cover a wide range of agricultural products, including fresh fruit and vegetables, dry and dried produce, seed potatoes, meat, cut flowers, eggs and egg products. Any member of the United Nations can participate, on an equal footing, in the activities of the Working Party. For more information on agricultural standards, please visit our website http://www.unece.org/trade/agr/welcome.html. The new Standard for Pine Nut Kernels is based on document ECE/TRADE/C/WP.7/2013/31, reviewed and adopted by the Working Party at its sixty-ninth session. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the United Nations Secretariat concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Mention of company -

The Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Bird Conservation Plan

The Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Bird Conservation Plan A Strategy for Protecting and Managing Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Habitats and Associated Birds in California A Project of California Partners in Flight and PRBO Conservation Science The Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Bird Conservation Plan A Strategy for Protecting and Managing Coastal Scrub and Chaparral Habitats and Associated Birds in California Version 2.0 2004 Conservation Plan Authors Grant Ballard, PRBO Conservation Science Mary K. Chase, PRBO Conservation Science Tom Gardali, PRBO Conservation Science Geoffrey R. Geupel, PRBO Conservation Science Tonya Haff, PRBO Conservation Science (Currently at Museum of Natural History Collections, Environmental Studies Dept., University of CA) Aaron Holmes, PRBO Conservation Science Diana Humple, PRBO Conservation Science John C. Lovio, Naval Facilities Engineering Command, U.S. Navy (Currently at TAIC, San Diego) Mike Lynes, PRBO Conservation Science (Currently at Hastings University) Sandy Scoggin, PRBO Conservation Science (Currently at San Francisco Bay Joint Venture) Christopher Solek, Cal Poly Ponoma (Currently at UC Berkeley) Diana Stralberg, PRBO Conservation Science Species Account Authors Completed Accounts Mountain Quail - Kirsten Winter, Cleveland National Forest. Greater Roadrunner - Pete Famolaro, Sweetwater Authority Water District. Coastal Cactus Wren - Laszlo Szijj and Chris Solek, Cal Poly Pomona. Wrentit - Geoff Geupel, Grant Ballard, and Mary K. Chase, PRBO Conservation Science. Gray Vireo - Kirsten Winter, Cleveland National Forest. Black-chinned Sparrow - Kirsten Winter, Cleveland National Forest. Costa's Hummingbird (coastal) - Kirsten Winter, Cleveland National Forest. Sage Sparrow - Barbara A. Carlson, UC-Riverside Reserve System, and Mary K. Chase. California Gnatcatcher - Patrick Mock, URS Consultants (San Diego). Accounts in Progress Rufous-crowned Sparrow - Scott Morrison, The Nature Conservancy (San Diego). -

Plants Used in Basketry by the California Indians

PLANTS USED IN BASKETRY BY THE CALIFORNIA INDIANS BY RUTH EARL MERRILL PLANTS USED IN BASKETRY BY THE CALIFORNIA INDIANS RUTH EARL MERRILL INTRODUCTION In undertaking, as a study in economic botany, a tabulation of all the plants used by the California Indians, I found it advisable to limit myself, for the time being, to a particular form of use of plants. Basketry was chosen on account of the availability of material in the University's Anthropological Museum. Appreciation is due the mem- bers of the departments of Botany and Anthropology for criticism and suggestions, especially to Drs. H. M. Hall and A. L. Kroeber, under whose direction the study was carried out; to Miss Harriet A. Walker of the University Herbarium, and Mr. E. W. Gifford, Asso- ciate Curator of the Museum of Anthropology, without whose interest and cooperation the identification of baskets and basketry materials would have been impossible; and to Dr. H. I. Priestley, of the Ban- croft Library, whose translation of Pedro Fages' Voyages greatly facilitated literary research. Purpose of the sttudy.-There is perhaps no phase of American Indian culture which is better known, at least outside strictly anthro- pological circles, than basketry. Indian baskets are not only concrete, durable, and easily handled, but also beautiful, and may serve a variety of purposes beyond mere ornament in the civilized household. Hence they are to be found in. our homes as well as our museums, and much has been written about the art from both the scientific and the popular standpoints. To these statements, California, where American basketry. -

Idaho's Registry of Champion Big Trees 06.13.2019 Yvonne Barkley, Director Idaho Big Tree Program TEL: (208) 885-7718; Email: [email protected]

Idaho's Registry of Champion Big Trees 06.13.2019 Yvonne Barkley, Director Idaho Big Tree Program TEL: (208) 885-7718; Email: [email protected] The Idaho Big Tree Program is part of a national program to locate, measure, and recognize the largest individual tree of each species in Idaho. The nominator(s) and owner(s) are recognized with a certificate, and the owners are encouraged to help protect the tree. Most states, including Idaho, keep records of state champion trees and forward contenders to the national program. To search the National Registry of Champion Big Trees, go to http://www.americanforests.org/bigtrees/bigtrees- search/ The National Big Tree program defines trees as woody plants that have one erect perennial stem or trunk at least 9½ inches in circumference at DBH, with a definitively formed crown of foliage and at least 13 feet in height. There are more than 870 species and varieties eligible for the National Register of Big Trees. Hybrids, minor varieties, and cultivars are excluded from the National listing but all but cultivars are accepted for the Idaho listing. The currently accepted scientific and common names are from the USDA Plants Database (PLANTS) http://plants.usda.gov/java/ and the Integrated Taxonomic Information System (ITIS) http://www.itis.gov/ Champion trees status is awarded using a point system. To calculate a tree’s total point value, American Forests uses the following equation: Trunk circumference (inches) + height (feet) + ¼ average crown spread (feet) = total points. The registered champion tree is the one in the nation with the most points. -

Wildland Fire in Ecosystems: Effects of Fire on Fauna

United States Department of Agriculture Wildland Fire in Forest Service Rocky Mountain Ecosystems Research Station General Technical Report RMRS-GTR-42- volume 1 Effects of Fire on Fauna January 2000 Abstract _____________________________________ Smith, Jane Kapler, ed. 2000. Wildland fire in ecosystems: effects of fire on fauna. Gen. Tech. Rep. RMRS-GTR-42-vol. 1. Ogden, UT: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Research Station. 83 p. Fires affect animals mainly through effects on their habitat. Fires often cause short-term increases in wildlife foods that contribute to increases in populations of some animals. These increases are moderated by the animals’ ability to thrive in the altered, often simplified, structure of the postfire environment. The extent of fire effects on animal communities generally depends on the extent of change in habitat structure and species composition caused by fire. Stand-replacement fires usually cause greater changes in the faunal communities of forests than in those of grasslands. Within forests, stand- replacement fires usually alter the animal community more dramatically than understory fires. Animal species are adapted to survive the pattern of fire frequency, season, size, severity, and uniformity that characterized their habitat in presettlement times. When fire frequency increases or decreases substantially or fire severity changes from presettlement patterns, habitat for many animal species declines. Keywords: fire effects, fire management, fire regime, habitat, succession, wildlife The volumes in “The Rainbow Series” will be published during the year 2000. To order, check the box or boxes below, fill in the address form, and send to the mailing address listed below. -

ISA Certified Arborist Exam Tree List Northern Nevada

ISA Certified Arborist Exam Tree List May 2007 Page 1 Northern Nevada Common Name Botanical Name 1. American Arborvitae Thuja occidentalis 2. American Elm Ulmus americana 3. American Linden Tilia americana 4. Amur Maple Acer ginnala 5. Arizona Cypress Cupressus arizonica 6. Austrian Pine Pinus nigra 7. Baldcypress Taxodium distichum 8. Black Locust Robinia pseudoacacia 9. Black Walnut Juglans nigra 10. Blue Ash Fraxinus quadrangulata 11. Blue Atlas Cedar Cedrus atlantica 'Glauca' 12. Border Pine Pinus strobiformis 13. Box Elder Acer negundo 14. Bristlecone Pine Pinus aristata 15. Bur Oak Quercus macrocarpa 16. Callery Pear Pyrus calleryana 17. Canada Red Chokecherry Prunus virginiana 18. Colorado Blue Spruce Picea pungens 'Glauca' 19. Common Hackberry Celtis occidentalis 20. Dawn Redwood Metasequoia glyptostroboides 21. Deodar Cedar Cedrus deodara 22. Douglas Fir Pseudotsuga menziesii 23. Eastern Redbud Cercis canadensis 24. English Oak Quercus robur 25. English Walnut Juglans regia 26. European Beech Fagus sylvatica 27. European Hornbeam Carpinus betulus 28. European Mountain Ash Sorbus aucuparia 29. European White Birch Betula pendula 30. Flowering Crabapple Malus spp. 31. Flowering Dogwood (many species) Cornus florida 32. Fremont Western Cottonwood Populus fremontii 33. Giant Sequoia Sequoiadendron giganteum 34. Ginkgo Ginkgo biloba 35. Golden Rain Tree Koelreuteria paniculata 36. Golden-Chain Tree Laburnum watereri 37. Green Ash Fraxinus pennsylvanica 38. Hawthorn (many species) Crataeus spp. 39. Honey Locust Gleditsia triacanthos 40. Horse Chestnut Aesculus hippocastanum ISA Certified Arborist Exam Tree List May 2007 Page 2 Northern Nevada Common Name Botanical Name 41. Idaho Locust Robinia x ambigua 'Idahoensis' 42. Japanese Black Pine Pinus thunbergiana 43. Incense Cedar Calocedrus decurrens 44. -

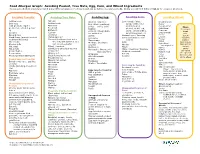

Avoiding Peanut, Tree Nuts, Egg, Corn, and Wheat Ingredients Common Food Allergens May Be Listed Many Different Ways on Food Labels and Can Be Hidden in Common Foods

Food Allergen Graph: Avoiding Peanut, Tree Nuts, Egg, Corn, and Wheat Ingredients Common food allergens may be listed many different ways on food labels and can be hidden in common foods. Below you will find different labels for common allergens. Avoiding Peanuts: Avoiding Tree Nuts: Avoiding Egg: Avoiding Corn: Avoiding Wheat: Artificial nuts Almond Albumin / albumen Corn - meal, flakes, Bread Crumbs Beer nuts Artificial nuts Egg (dried, powdered, syrup, solids, flour, Bulgur Cold pressed, expeller Brazil nut solids, white, yolk) niblets, kernel, Cereal extract Flour: pressed or extruded peanut Beechnut Eggnog alcohol, on the cob, Club Wheat all-purpose Butternut oil Globulin / Ovoglobulin starch, bread,muffins Conscous bread Goobers Cashew Fat subtitutes sugar/sweetener, oil, Cracker meal cake Durum Ground nuts Chestnut Livetin Caramel corn / flavoring durum Einkorn Mandelonas (peanuts soaked Chinquapin nut Lysozyme Citric acid (may be corn enriched Emmer in almond flavoring) Coconut (really is a fruit not a based) graham Mayonnaise Farina Mixed nuts tree nut, but classified as a Grits high gluten Meringue (meringue Hydrolyzed Monkey nuts nut on some charts) high protein powder) Hominy wheat protein Nut meat Filbert / hazelnut instant Ovalbumin Maize Kamut Gianduja -a chocolate-nut mix pastry Nut pieces Ovomucin / Ovomucoid / Malto / Dextrose / Dextrate Matzoh Peanut butter Ginkgo nut Modified cornstarch self-rising Ovotransferrin Matzoh meal steel ground Peanut flour Hickory nut Polenta Simplesse Pasta stone ground Peanut protein hydrolysate -

Ecosystems and Diversity of the Sierra Madre Occidental

Ecosystems and Diversity of the Sierra Madre Occidental M. S. González-Elizondo, M. González-Elizondo, L. Ruacho González, I.L. Lopez Enriquez, F.I. Retana Rentería, and J.A. Tena Flores CIIDIR I.P.N. Unidad Durango, Mexico Abstract—The Sierra Madre Occidental (SMO) is the largest continuous ignimbrite plate on Earth. Despite its high biological and cultural diversity and enormous environmental and economical importance, it is yet not well known. We describe the vegetation and present a preliminary regionalization based on physio- graphic, climatic, and floristic criteria. A confluence of three main ecoregions in the area corresponds with three ecosystems: Temperate Sierras (Madrean), Semi-Arid Highlands (Madrean Xerophylous) and Tropical Dry Forests (Tropical). The Madrean region harbors five major vegetation types: pine forests, mixed conifer forests, pine-oak forests, oak forests and temperate mesophytic forests. The Madrean Xerophylous region has oak or pine-oak woodlands and evergreen juniper scrub with transitions toward the grassland and xerophylous scrub areas of the Mexican high plateau. The Tropical ecosystem, not discussed here, includes tropical deciduous forests and subtropical scrub. Besides fragmentation and deforestation resulting from anthropogenic activities, other dramatic changes are occurring in the SMO, including damage caused by bark beetles (Dendroctonus) in extensive areas, particularly in drought-stressed forests, as well as the expansion of chaparral and Dodoneaea scrub at the expense of temperate forest and woodlands. Comments on how these effects are being addressed are made. Introduction as megacenters of plant diversity: northern Sierra Madre Occidental and the Madrean Archipelago (Felger and others 1997) and the Upper The Sierra Madre Occidental (SMO) or Western Sierra Madre is the Mezquital River region (González-Elizondo 1997). -

Pinus Monophylla

One of a Kind: Pinus monophylla Nancy Rose ’ve led many plant identification classes and Pinus monophylla grows in a semi-arid native walks in my career as a horticulturist. When range that runs from northern Baja California to Iit comes to pines (Pinus), I’ve taught that southern and eastern California, Nevada, the pines always carry multiple needles grouped southeastern corner of Idaho, western Utah, in fascicles (bundles), which readily differenti- and parts of Arizona and New Mexico. It is cold ates them from spruces (Picea) and firs (Abies) hardy enough (USDA Zone 6, average annual (the other common “tall, pointy evergreens”), minimum temperature -10 to 0°F [-23.3 to which both bear single needles. To then identify -17.8°C]) for Boston, but our much wetter cli- individual pine species, the first step is to see mate may be part of the reason this pine has if the bundles hold two, three, or five needles. been difficult to grow at the Arboretum. That’s still good advice about 99 percent of the We have tried a number of P. monophylla time, but when I came to the Arnold Arbore- accessions through the years, the first one in tum I discovered a notable exception to those 1908, but we currently have no living speci- rules: Pinus monophylla, the single-leaf pine. mens in the collections. The last one was Pinus monophylla is a member of the pine accession 400-88-B, which was a repropagation family (Pinaceae) and is one of 114 species in (by grafting) of a 1964 accession (287-64), which the genus Pinus. -

University of Nevada, Reno the Effects of Climate on Singleleaf Pinyon Pine Cone Production Across an Elevational Gradient A

University of Nevada, Reno The Effects of Climate on Singleleaf Pinyon Pine Cone Production across an Elevational Gradient A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF SCIENCE, WILDLIFE ECOLOGY AND CONSERVATION by Britney Khuu Miranda Redmond, Thesis Advisor Peter Weisberg, Thesis Advisor May 2017 UNIVERSITY OF NEVADA THE HONORS PROGRAM RENO We recommend that the thesis prepared under our supervision by BRITNEY KHUU entitled The Effects of Climate on Singleleaf Pinyon Pine Cone Production across an Elevational Gradient be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF SCIENCE, WILDLIFE ECOLOGY AND CONSERVATION ______________________________________________ Peter Weisberg, Ph. D., Thesis Advisor ______________________________________________ Tamara Valentine, Ph. D., Director, Honors Program May 2017 i Abstract Climate change affects forest structure and composition through increasing temperatures and altered precipitation regimes. Arid and semi-arid ecosystems have shown signs of susceptibility towards regional warming. Climate warming may negatively affect tree reproduction, which is an important factor in tree population dynamics. The relationship between climate change and tree reproduction is not fully understood, particularly in mast seeding tree species. This project aims to determine how climate affects seed production across an elevational gradient in singleleaf pinyon pine (Pinus monophylla), a dominant, widespread mast seeding conifer of the Great Basin. Historical cone production data were collected and reconstructed for the past 15 years at three sites that span an elevational gradient on Rawe Peak near Dayton, Nevada. The low elevation site had only one year of high seed cone production; therefore, seed production data were not sufficient enough to test any relationships between cone production and climate.