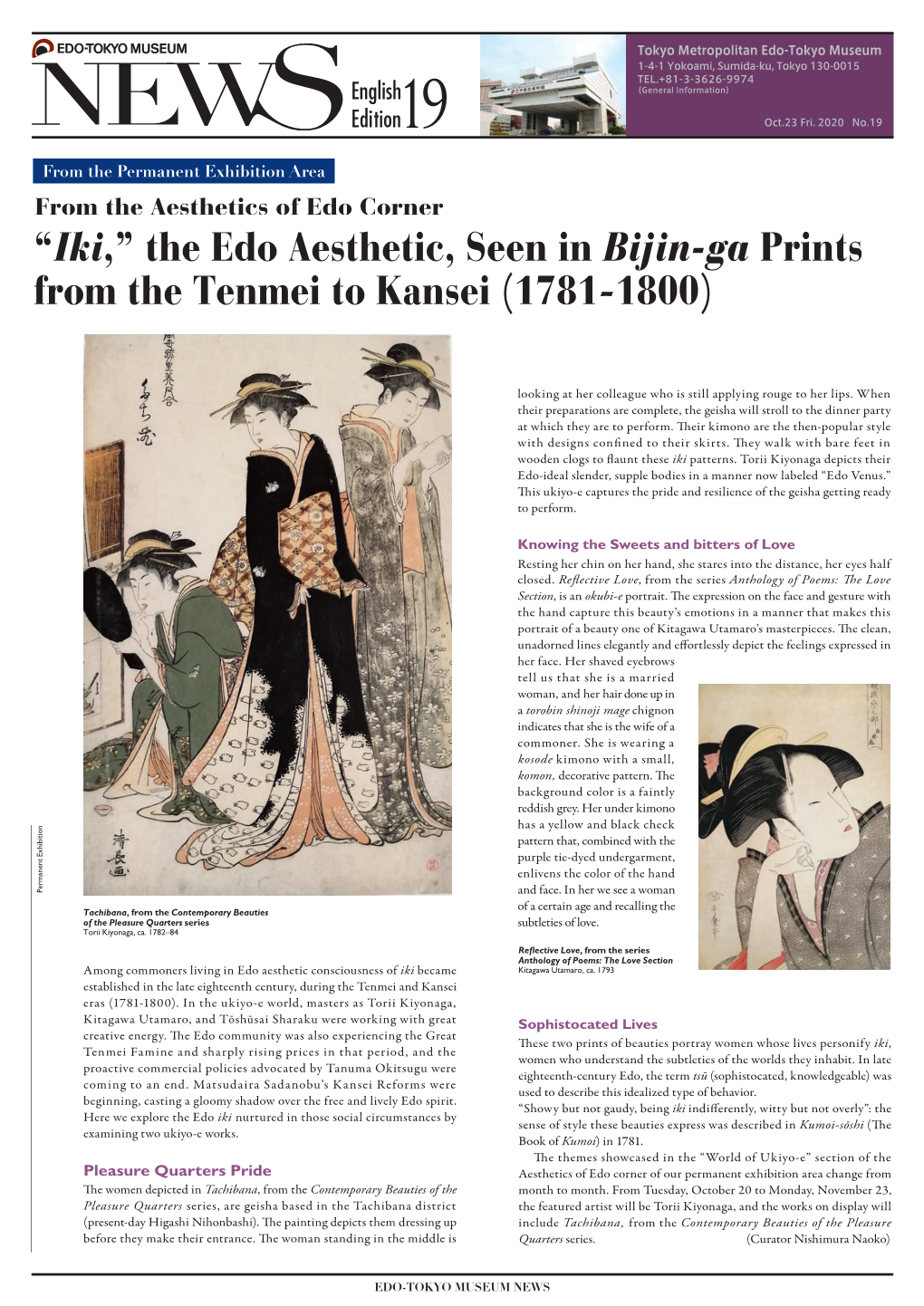

“Iki,” the Edo Aesthetic, Seen in Bijin-Ga Prints from the Tenmei To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’S Daughters – Part 2

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations School of Arts and Sciences October 2012 Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 2 Cecilia S. Seigle Ph.D. University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc Part of the Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Seigle, Cecilia S. Ph.D., "Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 2" (2012). Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations. 8. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/8 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/8 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 2 Abstract This section discusses the complex psychological and philosophical reason for Shogun Yoshimune’s contrasting handlings of his two adopted daughters’ and his favorite son’s weddings. In my thinking, Yoshimune lived up to his philosophical principles by the illogical, puzzling treatment of the three weddings. We can witness the manifestation of his modest and frugal personality inherited from his ancestor Ieyasu, cohabiting with his strong but unconventional sense of obligation and respect for his benefactor Tsunayoshi. Disciplines Family, Life Course, and Society | Inequality and Stratification | Social and Cultural Anthropology This is available at ScholarlyCommons: https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/8 Weddings of Shogun’s Daughters #2- Seigle 1 11Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 2 e. -

Publisbing Culture in Eighteentb-Century Japan: the Case of the Edo Publisher Tsutaya Jqzaburô (1751-97)

Publisbing Culture in Eighteentb-Century Japan: The Case of the Edo Publisher Tsutaya JQzaburô (1751-97) Yu Chang A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Department of East Asian Studies University of Toronto 0 Copyright by Yu Chang 1997 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 1*1 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliogtaphic Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395. rue Wellingtm Ottawa ON K1A ON4 OnawaOFJ KlAW Canada Canada The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence diowing the exclusive permettant à la National Librq of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or seil reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of this thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/nlm, de reproduction sur papier ou sur format électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in this thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thèse. thesis nor substantial extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or othenvise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author' s ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT Publishing Culture in Eighteentb-Century Japan: The Case of the Edo Pubüsher Tsutaya Jûzaburô (1750-97) Master of Arts, March 1997 Yu Chang Department of East Asian Studies During the ideologicai program of the Senior Councillor Mitsudaira Sadanobu of the Tokugawa bah@[ governrnent, Tsutaya JÛzaburÔ's aggressive publishing venture found itseif on a collision course with Sadanobu's book censorship policy. -

The Creation of the Term Kojin (Individual)

The Creation of the Term Kojin (Individual) Saitō Tsuyoshi The term kojin 個人 (individual)—meaning that element which gives form to the opposition between state and society, the person who enjoys a freedom and independence that allows for no intrusion by others or state power, and the subject of free and equal rights, among other things—took shape extraor- dinarily late. So far as I have been able to determine, the term kojin was coined to correspond to the European word “individual” in 1884 (Meiji 17). The fact that the word shakai 社會 (society), as I have discussed elsewhere,1 was first employed in the sense that it is presently used in 1875 (Meiji 8) means that 1884 is really quite late. However, kojin and shakai as concepts must have been born in the same period. Before kojin as a word emerged, there is little doubt that kojin as a concept [even if there was no specific word to articulate it] would surely have existed. When I looked for the words that express the concept of kojin, words with which intellectuals from the late-Edo period [1600–1867] through early Meiji [1868–1912] were experimenting, I learned of the long, painful road traveled by them until they struck upon this simple term. This was also something of a major shock. 1 Translation Equivalents for kojin through the Meiji Era The first Japanese translation given to correspond to “individual” or its equivalent in European languages appears to have been a word matched to the Dutch term individueel. The first head of the Bansho shirabesho 蕃書調 所 (Institute of barbarian books) was a man by the name of Koga Masaru 古賀增 (Kin’ichirō 謹一郎, Chakei 茶溪, 1816–1884). -

Keichū, Motoori Norinaga, and Kokugaku in Early Modern Japan

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles The Jeweled Broom and the Dust of the World: Keichū, Motoori Norinaga, and Kokugaku in Early Modern Japan A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Emi Joanne Foulk 2016 © Copyright by Emi Joanne Foulk 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Jeweled Broom and the Dust of the World: Keichū, Motoori Norinaga, and Kokugaku in Early Modern Japan by Emi Joanne Foulk Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2016 Professor Herman Ooms, Chair This dissertation seeks to reconsider the eighteenth-century kokugaku scholar Motoori Norinaga’s (1730-1801) conceptions of language, and in doing so also reformulate the manner in which we understand early modern kokugaku and its role in Japanese history. Previous studies have interpreted kokugaku as a linguistically constituted communitarian movement that paved the way for the makings of Japanese national identity. My analysis demonstrates, however, that Norinaga¾by far the most well-known kokugaku thinker¾was more interested in pulling a fundamental ontology out from language than tying a politics of identity into it: grammatical codes, prosodic rhythms, and sounds and their attendant sensations were taken not as tools for interpersonal communication but as themselves visible and/or audible threads in the fabric of the cosmos. Norinaga’s work was thus undergirded by a positive understanding ii of language as ontologically grounded within the cosmos, a framework he borrowed implicitly from the seventeenth-century Shingon monk Keichū (1640-1701) and esoteric Buddhist (mikkyō) theories of language. Through philological investigation into ancient texts, both Norinaga and Keichū believed, the profane dust that clouded (sacred, cosmic) truth could be swept away, as if by a jeweled broom. -

Politics, Classicism, and Medicine During the Eighteenth Century 十八世紀在德川日本 "頌華者" 和 "貶華者" 的 問題 – 以中醫及漢方為主

East Asian Science, Technology and Society: an International Journal DOI 10.1007/s12280-008-9042-9 Sinophiles and Sinophobes in Tokugawa Japan: Politics, Classicism, and Medicine During the Eighteenth Century 十八世紀在德川日本 "頌華者" 和 "貶華者" 的 問題 – 以中醫及漢方為主 Benjamin A. Elman Received: 12 May 2008 /Accepted: 12 May 2008 # National Science Council, Taiwan 2008 Abstract This article first reviews the political, economic, and cultural context within which Japanese during the Tokugawa era (1600–1866) mastered Kanbun 漢 文 as their elite lingua franca. Sino-Japanese cultural exchanges were based on prestigious classical Chinese texts imported from Ming (1368–1644) and Qing (1644–1911) China via the controlled Ningbo-Nagasaki trade and Kanbun texts sent in the other direction, from Japan back to China. The role of Japanese Kanbun teachers in presenting language textbooks for instruction and the larger Japanese adaptation of Chinese studies in the eighteenth century is then contextualized within a new, socio-cultural framework to understand the local, regional, and urban role of the Confucian teacher–scholar in a rapidly changing Tokugawa society. The concluding part of the article is based on new research using rare Kanbun medical materials in the Fujikawa Bunko 富士川文庫 at Kyoto University, which show how some increasingly iconoclastic Japanese scholar–physicians (known as the Goiha 古醫派) appropriated the late Ming and early Qing revival of interest in ancient This article is dedicated to Nathan Sivin for his contributions to the History of Science and Medicine in China. Unfortunately, I was unable to present it at the Johns Hopkins University sessions in July 2008 honoring Professor Sivin or include it in the forthcoming Asia Major festschrift in his honor. -

The Durability of the Bakuhan Taisei Is Stunning

Tokugawa Yoshimune versus Tokugawa Muneharu: Rival Visions of Benevolent Rule by Tim Ervin Cooper III A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Mary Elizabeth Berry, Chair Professor Irwin Scheiner Professor Susan Matisoff Fall 2010 Abstract Tokugawa Yoshimune versus Tokugawa Muneharu: Rival Visions of Benevolent Rule by Tim Ervin Cooper III Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Mary Elizabeth Berry, Chair This dissertation examines the political rivalry between the eighth Tokugawa shogun, Yoshimune (1684‐1751, r. 1716‐45), and his cousin, the daimyo lord of Owari domain, Tokugawa Muneharu (1696‐1764, r. 1730‐39). For nearly a decade, Muneharu ruled Owari domain in a manner that directly contravened the policies and edicts of his cousin, the shogun. Muneharu ignored admonishments of his behavior, and he openly criticized the shogun’s Kyōhō era (1716‐36) reforms for the hardship that they brought people throughout Japan. Muneharu’s flamboyance and visibility transgressed traditional status boundaries between rulers and their subjects, and his lenient economic and social policies allowed commoners to enjoy the pleasures and profits of Nagoya entertainment districts that were expanding in response to the Owari lord’s personal fondness for the floating world. Ultimately, Muneharu’s fiscal extravagance and moral lenience—benevolent rule (jinsei), as he defined it—bankrupted domain coffers and led to his removal from office by Yoshimune. Although Muneharu’s challenge to Yoshimune’s political authority ended in failure, it nevertheless reveals the important role that competing notions of benevolence (jin) were coming to play in the rhetoric of Tokugawa rulership. -

Age of the Dandy: the Flowering of Yoshiwara Arts

5 Age of the Dandy: The Flowering of Yoshiwara Arts Kiragawa Uramaro. Two geisha in typical niwaka festival attire with their hair dressed in the style of a young man. Ohide of the Tamamura-ya, seated, is receiving shamisen instruc- tion from Toyoshina of the Tomimoto school, ca. 1789. Courtesy of n 1751, Tanuma Okitsugu, a politician who left a significant mark on Christie’s New York. the second half of the eighteenth century, was one of many osobashti I serving the ninth shogun Ieshige. Osobashti were secretaries who con- veyed messages between the shogun and counselors, a position of a modest income, which in Tanuma’s case carried an annual salary of 150 koku. By 1767, Tanuma was receiving approximately 20,000 koku as the personal secretary to the tenth shogun, Ieharu. Two years later, with a salary of 57,000 koku, Tanuma was a member of the powerful shogunate council. Although examples of favoritism and extravagant promotion had occurred under the previous shoguns Tsunayoshi and Ienobu, there was no precedent for the degree of actual power Tanuma Okitsugu had assumed. He won his position through a combination of superior intelligence, political skill, and personal charm. In addition, he made unscrupulous use of bribery to coun- selors in key positions and ladies of the shogun’s harem.1 In 1783, after his son Okitomo’s name was added to the shogun’s select list of counselors, father and son virtually ruled Japan. Kitagawa Utamaro. Komurasaki of To strengthen the nation’s economy, Tanuma Okitsugu allied himself the Great Miura and her lover Shirai with the commercial powers of Edo and Osaka and promoted industry and Gonpachi (discussed in Chapter 3). -

The History of Merrymaking In

The 50th anniversary of the Suntory Foundation for the Arts Styles of Play: The History of Merrymaking in Art ● = National Treasure ◎ = Important Cultural Property June 26 to August 18, 2019 Suntory Museum of Art = Now on View ○ = Important Art Object 6/26 7/17 7/24 7/31 ▼▼▼ ▼▼▼ ▼▼▼ ▼▼▼ No. Title Artist Period Collection 7/15 7/22 7/29 8/18 Section 1: The World of “Customs, Month by Month”: Play as Part of Life 7/10 ~ ◎ scene change 1 Customs, Month by Month, Throughout the Twelve Months of the Year Momoyama period, 16th-17th century Hoshun Yamaguchi Memorial Hall 2 Customs, Month by Month Edo period, 17th century Suntory Museum of Art 3 Precious Children's Games of the Five Festivals Torii Kiyonaga Edo period, dated Kansei 7-8 (1795-1796) Suntory Museum of Art Section 2: The Origins of Enjoyment: Cultivated Pleasures to Relish with All Five Senses scene Painting by Sumiyoshi Jyokei, 4 The Tale of Genji Edo period, 17th century Suntory Museum of Art change inscription by Sono Motoyoshi 5 Suma and Hashihime, Scenes from the Tale of Genji Tosa school Edo period, 17th century Suntory Museum of Art 6 The Tale of Joruri Muromachi period, 16th century Suntory Museum of Art 7 Sugoroku Game Board with Floral Design in Maki-e Edo period, 19th century Kyoto National Museum scene 8 Tsurezure-gusa (Essays in Idleness) Kaiho Yusetsu Edo period, 17th century Suntory Museum of Art change 9 Customs (Japanese and Chinese Amusements) Edo period, 17th century Private Collection scene 10 Fan Papers Decorated with Amusements Edo period, 17th century Hosomi -

To Ise at All Costs Religious and Economic Implications of Early Modern Nukemairi

Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 33/1: 75–114 © 2006 Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture Laura Nenzi To Ise at All Costs Religious and Economic Implications of Early Modern Nukemairi If pilgrimages are ideal platforms for contention, nowhere more than in early modern nukemairi did tensions come to the fore so prominently, and contrast- ing interests clash so stridently. This article looks at Edo-period (1600–1868) unauthorized pilgrimages to highlight the inherent disjunctions between the interests of the individual and those of the community, and between the pri- orities of faith and the practical necessities of the economy. It also follows the evolution of nukemairi over time by looking at the repercussions that the fis- cal reforms of the late eighteenth century had on the identification of travelers as “runaways.” keywords: Ise – nukemairi – okagemairi – money – alms – pilgrimage – travel – recreation – economy – Konno Oito Laura Nenzi is Assistant Professor of History at Florida International University. Her main field of interest is the culture of travel in early modern Japan. 75 n a work titled Shokoku nukemairi yume monogatari 諸国抜参夢物語 [Tale of a dream about nukemairi in various provinces, 1771], the author Zedōshi 是道子 describes a distinct type of religious journey that remained popular Ithroughout the Edo or Tokugawa period (1600–1868). He writes: I do not know at what point in time nukemairi began. A long, long time ago, at the end of the Tenshō era [1573–1592], nukemairi were widely popular in Kyoto. […] In this year of the rabbit, Meiwa 8 [1771], spring has come early, and pil- grims from all provinces [have set out], needless to say, in large numbers. -

Removal of the Ban on Meat

The End of a 1,200-year-old Ban on the Eating of Meat Removal of the Ban on Meat Introduction Zenjiro Watanabe Mr. Watanabe was born in Tokyo in 1932 and In March 1854, the Tokugawa Shogunate concluded The graduated from Waseda University in 1956. In 1961, he received his Ph.D in commerce from Treaty of Peace and Amity between the United States and the same university and began working at the the Empire of Japan followed shortly by peace treaties National Diet Library. Mr. Watanabe worked there as manager of the with various Western countries such as England, The department that researches the law as it th applies to agriculture. He then worked as Netherlands, and Russia. 2004 marks the 150 anniversary manager of the department that researches foreign affairs, and finally he devoted himself to of this opening of Japan’s borders to other nations. research at the Library. Mr. Watanabe retired in 1991 and is now head of a history laboratory researching various The opening of Japan’s borders, along with the restoration aspects of cities, farms and villages. Mr. Watanabe’s major works include Toshi to of political power to the Imperial court, was seen as an Noson no Aida—Toshikinko Nogyo Shiron, 1983, Ronsosha; Kikigaki •Tokyo no Shokuji, opportunity to aggressively integrate Western customs into edited 1987, Nobunkyo; Kyodai Toshi Edo ga Japanese culture. In terms of diet, removal of the long- Washoku wo Tsukutta, 1988, Nobunkyo; Nou no Aru Machizukuri, edited 1989, Gakuyo- standing social taboo against the eating of meat became a shobo; Tokyo ni Nochi ga Atte Naze Warui, collaboration 1991, Gakuyoshobo; Kindai symbol of this integration. -

Yosan-E and the Aesthetics of Post-Tenpo Reforms Era Sericulture Prints 61 S , One One , Which in Which 2) Yōsan-E )

ART RESEARCH vol.18 Yosan-e and The Aesthetics of Post-Tenpo Reforms Era Sericulture Prints Vanessa Tothill (立命館大学 日本デジタル・ヒューマニティーズ拠点 博士課程後期課程D5) E-mail [email protected] abstract Sericulture prints (yōsan-e), showing women industriously cultivating silkworms, were a publishing trend that emerged in the late-eighteenth century, possibly in response to the growth of Japanese silk production and the spread of commercial agricultural practices. yōsan-e combined the content of informative agricultural texts (nōsho) with the aesthetic conventions of 'pictures of beauties' (bijinga) - an ukiyo-e genre commonly associated with the depiction of urban prostitutes and teahouse waitresses. An analysis of the text- image compositions published before and after the Tenpō Reforms (1841-1843) reveals how, in a small number of cases, nishiki-e publishers and kyōka poets exploited the official narratives of filial piety (kō) and diligence (kinben) as part of a larger strategy to allow for the continued production of prints of beauties during periods of heightened censorship. Introduction When looking at Edo-period yōsan-e, one should bear in mind that a large portion of the population was forbidden to wear silk by official This article will focus on three mid-nineteenth sumptuary laws that restricted the consumption century yōsan-e series, which depict silk cultivation: of luxury products. Excessive expenditure was from the careful handling of the egg papers, to linked to immorality, mainly because it could the reeling of raw silk from boiled cocoons by lead to insolvency, but also because it blurred the Yosan-e young female sericulturists. The kyōka poems that distinction between those of high and low status. -

Monumenta Nipponica Style Sheet

Monumenta Nipponica Style Sheet Completely revised edition SOPHIA UNIVERSITY, TOKYO Monumenta Nipponica Style Sheet Completely revised edition (May 2017) Sophia University 7–1 Kioi-chō, Chiyoda-ku Tokyo 102-8554 Tel: 81-3-3238-3543; Fax: 81-3-3238-3835 e-mail: [email protected] Website: http://dept.sophia.ac.jp/monumenta Copyright 2017 by Sophia University, all rights reserved. CONTENTS 1 GENERAL DIRECTIONS 1 1.1. Preparation of Manuscripts 1 1.2. Copyright 1 2 OVERVIEW OF STYLISTIC CONVENTIONS 2 2.1. Italics/Japanese Terms 2 2.2. Macrons and Plurals 2 2.3. Romanization 2 2.3.1. Word division 3 2.3.2. Use of hyphens 3 2.3.3. Romanization of Chinese and Korean names and terms 4 2.4. Names 4 2.5. Characters (Kanji/Kana) 4 2.6. Translation and Transcription of Japanese Terms and Phrases 4 2.7. Dates 5 2.8. Spelling, Punctuation, and Capitalization of Western Terms 5 2.9. Parts of a Book 6 2.10. Numbers 6 2.11. Transcription of Poetry 6 3 TREATMENT OF NAMES AND TERMS 7 3.1. Personal Names 7 3.1.1. Kami, Buddhist deities, etc. 7 3.1.2. “Go” emperors 7 3.1.3. Honorifics 7 3.2. Names of Companies, Publishers, Associations, Schools, Museums 7 3.3. Archives and Published Collections 8 3.4. Names of Prefectures, Provinces, Villages, Streets 8 3.5. Topographical Names 9 3.6. Religious Institutions and Palaces 9 3.7. Titles 10 3.7.1. Emperors, etc. 10 3.7.2. Retired emperors 10 3.7.3.