My Iranian Sukkah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Leket-Israel-Passove

Leave No Crumb Behind: Leket Israel’s Cookbook for Passover & More Passover Recipes from Leket Israel Serving as the country’s National Food Bank and largest food rescue network, Leket Israel works to alleviate the problem of nutritional insecurity among Israel’s poor. With the help of over 47,000 annual volunteers, Leket Israel rescues and delivers more than 2.2 million hot meals and 30.8 million pounds of fresh produce and perishable goods to underprivileged children, families and the elderly. This nutritious and healthy food, that would have otherwise gone to waste, is redistributed to Leket’s 200 nonprofit partner organizations caring for the needy, reaching 175,000+ people each week. In order to raise awareness about food waste in Israel and Leket Israel’s solution of food rescue, we have compiled this cookbook with the help of leading food experts and chefs from Israel, the UK , North America and Australia. This book is our gift to you in appreciation for your support throughout the year. It is thanks to your generosity that Leket Israel is able to continue to rescue surplus fresh nutritious food to distribute to Israelis who need it most. Would you like to learn more about the problem of food waste? Follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter or visit our website (www.leket.org/en). Together, we will raise awareness, continue to rescue nutritious food, and make this Passover a better one for thousands of Israeli families. Happy Holiday and as we say in Israel – Beteavon! Table of Contents Starters 4 Apple Beet Charoset 5 Mina -

Chanukah Cooking with Chef Michael Solomonov of the World

Non-Profit Org. U.S. POSTAGE PAID Pittsfield, MA Berkshire Permit No. 19 JEWISHA publication of the Jewish Federation of the Berkshires, serving V the Berkshires and surrounding ICE NY, CT and VT Vol. 28, No. 9 Kislev/Tevet 5781 November 23 to December 31, 2020 jewishberkshires.org Chanukah Cooking with Chef The Gifts of Chanukah Michael Solomonov of the May being more in each other’s presence be among World-Famous Restaurant Zahav our holiday presents On Wednesday, December 2 at 8 p.m., join Michael Solomonov, execu- tive chef and co-owner of Zahav – 2019 James Beard Foundation award winner for Outstanding Restaurant – to learn to make Apple Shrub, Abe Fisher’s Potato Latkes, Roman Artichokes with Arugula and Olive Oil, Poached Salmon, and Sfenj with Cinnamon and Sugar. Register for this live virtual event at www.tinyurl.com/FedCooks. The event link, password, recipes, and ingredient list will be sent before the event. Chef Michael Solomonov was born in G’nai Yehuda, Israel, and raised in Pittsburgh. At the age of 18, he returned to Israel with no Hebrew language skills, taking the only job he could get – working in a bakery – and his culinary career was born. Chef Solomonov is a beloved cham- pion of Israel’s extraordinarily diverse and vibrant culinary landscape. Chef Michael Solomonov Along with Zahav in Philadelphia, Solomonov’s village of restaurants include Federal Donuts, Dizengoff, Abe Inside Fisher, and Goldie. In July of 2019, Solomonov brought BJV Voluntary Subscriptions at an another significant slice of Israeli food All-Time High! .............................................2 culture to Philadelphia with K’Far, an Distanced Holidays? Been There, Israeli bakery and café. -

Considerations About Semitic Etyma in De Vaan's Latin Etymological Dictionary

applyparastyle “fig//caption/p[1]” parastyle “FigCapt” Philology, vol. 4/2018/2019, pp. 35–156 © 2019 Ephraim Nissan - DOI https://doi.org/10.3726/PHIL042019.2 2019 Considerations about Semitic Etyma in de Vaan’s Latin Etymological Dictionary: Terms for Plants, 4 Domestic Animals, Tools or Vessels Ephraim Nissan 00 35 Abstract In this long study, our point of departure is particular entries in Michiel de Vaan’s Latin Etymological Dictionary (2008). We are interested in possibly Semitic etyma. Among 156 the other things, we consider controversies not just concerning individual etymologies, but also concerning approaches. We provide a detailed discussion of names for plants, but we also consider names for domestic animals. 2018/2019 Keywords Latin etymologies, Historical linguistics, Semitic loanwords in antiquity, Botany, Zoonyms, Controversies. Contents Considerations about Semitic Etyma in de Vaan’s 1. Introduction Latin Etymological Dictionary: Terms for Plants, Domestic Animals, Tools or Vessels 35 In his article “Il problema dei semitismi antichi nel latino”, Paolo Martino Ephraim Nissan 35 (1993) at the very beginning lamented the neglect of Semitic etymolo- gies for Archaic and Classical Latin; as opposed to survivals from a sub- strate and to terms of Etruscan, Italic, Greek, Celtic origin, when it comes to loanwords of certain direct Semitic origin in Latin, Martino remarked, such loanwords have been only admitted in a surprisingly exiguous num- ber of cases, when they were not met with outright rejection, as though they merely were fanciful constructs:1 In seguito alle recenti acquisizioni archeologiche ed epigrafiche che hanno documen- tato una densità finora insospettata di contatti tra Semiti (soprattutto Fenici, Aramei e 1 If one thinks what one could come across in the 1890s (see below), fanciful constructs were not a rarity. -

Catering Menu

Catering (Collection only) Minimum order £100 Deluxe falafel platter £115 mezze-salads, dips platter £115 40 Large homemade falafel balls, Israeli Feeds 6 - 8 Hummus, tzatziki, Israeli salad, Tabouli Feeds 6 - 8 salad, hummus, Tabouli salad, Tangy People salad, aubergine & pine nuts salad, People cabbage slaw, pickles & shifka peppers, pickles, olives & shifka peppers, chilli Chilli harissa sauce, tahini sauce harissa sauce, Israeli pita(5), greek & Israeli pita(10) pita(5) Allergens: Cereals(gluten), sesame, soy Allergens: Cereals(gluten), sesame, soy, milk, nuts Extras: Extras: Homemade coleslaw + £15 With tangy cabbage slaw + £15 Char-grilled aubergine & tahini + £30 Char-grilled aubergine & tahini + £30 With homemade tzatziki + £15 With homemade tzatziki + £15 Falafel bar £12 pP Israeli tasting menu £26 pp 15 Person minimum order 15 Person minimum order 4 Large falafel balls per person Falafel bar or mezze platter menu Israeli salad, hummus, Tabouli salad, Tangy + Homemade chicken shawarma cabbage slaw, pickles & shifka peppers, + Chicken shashlik (skewers of chicken thigh/breast) chilli harissa sauce, tahini sauce & + Amba sauce Israeli pita(1 pita per person) + Extra pita PP (Kosher meat available on request at extra cost) Allergens: Cereals(gluten), sesame, soy, milk Allergens: Cereals(gluten), sesame, soy, milk, nuts, celery Extras: With tangy cabbage slaw + £2.00 per person Meat dishes served in aluminium foil containers to be reheated on site With homemade tzatziki + £2.00 per person Extras: Homemade coleslaw + £2.00 per person Other options may be available on request With homemade tzatziki + £2.00 per person Box of falafel balls £20 box of smoky cauliflower £30 box of grilled AUBERGINE £30 25 Homemade large falafel balls, BBQ cauliflower with fresh turmeric, tahini, Char-grilled aubergine with garlic, served with tahini sumac, garlic & herbs oil & squeeze of lemon tahini, harissa oil, pine nuts, fresh green herbs & Zahatar. -

Marion: I Travelled from My Home in Toronto, Canada, to Brooklyn, New York, Because of Gefilte Fish

Marion: I travelled from my home in Toronto, Canada, to Brooklyn, New York, because of gefilte fish. Many Jewish foods are adored and celebrated but gefilte fish isn't one of them. Can two young authors and entrepreneurs restore its reputation? I'm Marion Kane, Food Sleuth®, and welcome to "Sittin' in the Kitchen®". Liz Alpern and Jeffrey Yoskowitz are co-authors of The Gefilte Manifesto and co-owners of The Gefilteria. Their goal is to champion Jewish foods like gefilte fish, give them a tasty makeover and earn them the respect they deserve. I first met Liz when she appeared on a panel at the Toronto Ashkenaz Festival. I knew immediately that I had to have her on my podcast. We talked at her apartment in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. Marion: Let's sit down and talk Ashkenazi food - and gefilte fish in particular. I'm going to ask you to introduce yourselves. Liz: My name's Liz Alpern. I am the co-owner of The Gefilteria and co-author of The Gefilte Manifesto. Jeffrey: My name is Jeffrey Yoskowitz. I am the co-owner and chief pickler of The Gefilteria, and I am a co-author of The Gefilte Manifesto cookbook. Marion: You're both Jewish and Ashkenazi. Liz: Yes, we're both of Eastern European Jewish descent. Marion: Gefilte fish - we have to address this matter. I want to read a description of gefilte fish of the worst kind. Quote, "Bland, intractably beige, and (most unforgivably of all) suspended in jelly, the bottled version seemed to have been fashioned, golem-like, from a combination of packing material and crushed hope." Liz & Jeffrey: (laugh) Marion: That's a very unfavorable review of gefilte fish. -

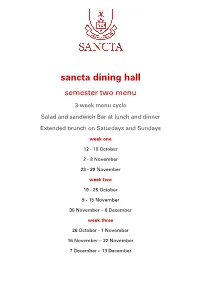

Sancta Dining Hall Semester Two Menu

sancta dining hall semester two menu 3-week menu cycle Salad and sandwich Bar at lunch and dinner Extended brunch on Saturdays and Sundays week one 12 - 18 October 2 - 8 November 23 - 29 November week two 19 - 25 October 9 - 15 November 30 November – 6 December week three 26 October - 1 November 16 November – 22 November 7 December – 13 December week one menu week one menu dates 12 - 18 October 2 - 8 November 23 - 29 November VG = Vegan V= Vegetarian GF = Gluten-free DF = Dairy-free WEEK ONE – MONDAY LUNCH Country NSW Kitchen theme Herb roasted chicken thighs DF GF Kidney Bean and Quinoa Balls VG GF DF Brown Rice with mushroom and garlic DF GF "Superfood Salad", Kale, Spinach, Peas, Grains & Seeds GF DF Roasted broccolini, paprika roasted cauliflower DF GF Tahini Salad Dressing, Soy Salad Dressing, Fresh Lemon wedges, Tartare Sauce, Herb Aioli, Tomato Sugo DINNER Roast Dinner Theme Roast Beef (gravy optional) DF GF Spiced Baked Lentil and Veggie Burgers VG GF DF White Potato Mash VG GF DF Minted Peas / Steamed Brussel Sprouts / Herb roasted vegetables: pumpkin, eggplant, capsicum / Cauliflower Bake Coconut Yoghurt with Fruit and Berries DF + Daily Gourmet Salad and Sandwich Bar + WEEK ONE - TUESDAY LUNCH Summer theme Mango chicken breast (chicken breast diced, cooked in mango slices and olive oil) DF GF Chickpea and Spinach Falafels GF DF Steamed Jasmine Rice GF DF Mixed Leaf Salad with mango slices GF DF DINNER (excludes 13 October Formal Dinner) Israeli theme 8-hour Slow Cooked Lamb Shoulder GF DF Chickpea Falafel VG, GF, DF Cinnamon -

View Paprika & Colbeh Full Menu

Catering for All Occasions | Gift Certificates Available FOR PICKUP & DELIVERY SCAN HERE TO ORDER ONLINE 32 W 39th Street New York, New York OU Certified (212) 354-8181 (212) 679-1100 www.colbeh.com www.paprikacater.com @colbencaterer @paprikakosher גלאט כשר OU Certified Download the app: Colbeh & Paprika Kosher HUMMUS PLATES SANDWICHES Choose A Bread: Served with Pickles $9.50 hummus falafel (gf,v) $13.50 original hummus (gf,v) *lafa $2 $13.50 Hummus Plate with Falafel Balls, Tahini, sabich *white baguette $2 *white wrap Eggplant, Hard Boiled Egg, Pickles, Tahini, and Pita hummus shawarma (gf) $17.50 *whole wheat wrap *white pita Harisa, and Amba Hummus Plate with Chicken Shawarma falafel (v) $9.50 shawarma $16.50 and Pita With Hummus, Cabbage Salad, Pickles APPETIZERS Hummus, Israeli Salad, Pickles, and Tahini $16.50 $17.50 soup of the day $9.50 french fries $8.50 malawach roll (v) pap burger Hard Boiled Egg, Israeli Salad, Hummus, 8oz. Juicy Beef Burger, Tomatoes, Lettuce, cauliflower over tahini $9.50 duck taco $14.50 Schug, Wrapped in a Yeminite Puff Pastry Pickles, Avocado, Garlic Aioli, Served on a (gf,v) Served with Enoki Mushrooms, Daikon Bread *add chicken $8.50 Bun Warm Cauliflower with Pine Nuts, Mint, and Radish in a Sweet Potato Shell Topped with $18.50 $18.50 Parsley over Tahini Scallions koobideh sandwich white koobideh sandwich Ground Beef Sandwich Ground Chicken Breast Sandwich arays $18.50 $14.50 shakshuka (gf,v) $13.50 Grilled Kebab Stuffed in a Pita to 3 Poached Eggs in a Tomato Stew and impossible burger (v) $17.50 cauliflower shawarma Perfection. -

Gefilte Fish CARTE

5 SENSES A LA CARTE IDENTITIES Gefilte Fish For many people gelte sh is the epitome of traditional Jewish cooking. It was served on Shabbat and other high holidays in the For about 26 patties: shtetl, the small towns in Eastern Europe shaped by Jewish 7–7 ½ pounds whole carp, whitesh, and culture. Housewives procured a living sh, usually a carp, which pike, lleted and ground* was then killed at home. They cut open the sh’s belly in such a 4 quarts (liter) cold water or to just cover way that they could remove the bones and meat without tearing 3 teaspoons salt or to taste the skin. After mixing the meat of the sh with matzo meal or 3 onions, peeled white bread, they lled the sh skin with the farce. This way, one 4 medium carrots, peeled sh was enough to satisfy the whole hungry family. Since 2 tablespoons sugar cooking is not permitted on Shabbat, the dish was prepared 1 small parsnip, chopped before it began and eaten cold. 3–4 large eggs Even though gelte sh can be found in all varieties of Ashkenazi freshly ground pepper to taste cuisine, there were two distinct ways to prepare it in Eastern ½ cold water Europe, separated by a clear geographical line. In southwest ⅓ cup matza meal Poland, Galicia, and German-speaking regions, people preferred * Have your shmonger grind the sh and ask him to eat their gelte sh sweet. By contrast, the so-called Litvaks, to save and give you the tails, ns, heads, and Jews from Lithuania and other regions under Russian inuence, bones. -

Adaptation, Immigration, and Identity: the Tensions of American Jewish Food Culture by Mariauna Moss Honors Thesis History Depa

Adaptation, Immigration, and Identity: The Tensions of American Jewish Food Culture By Mariauna Moss Honors Thesis History Department University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill 03/01/2016 Approved: _______________________ Karen Auerbach: Advisor _______________________ Chad Bryant: Advisor Table of Contents Acknowledgements Introduction 4 Chapter 1 12 Preparation: The Making of American Jewish Food Culture Chapter 2 31 Consumption: The Impact of Migration on Holocaust Survivor Food Culture Chapter 3 48 Interpretation: The Impact of the Holocaust on American-Jewish Food Culture Conclusion 66 2 Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my correspondents, Jay Ipson, Esther Lederman, and Kaja Finkler. Without each of your willingness to invite me into your homes and share your stories, this thesis would not have been possible. Kaja, I thank you especially for your continued support and guidance. Next, I want to give a shout-out to my family and friends, especially my fellow thesis writers, who listened to me talk about my thesis constantly and without a doubt saw the bulk of my negative stress reactions. Thank you all for being such a great support system. It is my hope that at least one of you will read this- here’s looking at you, Mom. Third, I would like to thank Professor Waterhouse for sticking with me throughout this entire process. I could not have done this without your constant kind words and encouragement (though I could have done without your negative commentary about Billy Joel). Thank you for making this possible. Finally, I extend the largest thank you to my wonderful thesis advisors, Professor Karen Auerbach and Professor Chad Bryant. -

A Collection of Passover Recipes Passed Down from Generation to Generation

Temple Beth El of South Orange County’s BE Sisters and Adult Education Present A Collection of Passover Recipes passed down from generation to generation pesach 2021 enjoy these Passover recipes that have been passed down and shared from members of our community. Wishing you a joyous Passover from BE Sisters and Adult Education! "These recipes do include kitniyot. While it is permissible to use on Passover, it is not everyone’s custom." Charoset & Appetizers, 11 Classic Charoset Charosis Crunchy, Chopped (more, please!) Charoset Sephardic Passover Charoset Hot & Spicy Mexican Gefilte Fish Gefilte Fish Beet Horseradish Mold Soups & Salads, 21 Matzah Balls From my mom Shari’s Matzo Balls Passover Soup Muffins Cucumber Salad Main Course, 26 Holiday Brisket Instant Pot Jewish Brisket One-Dish Chicken & Stuffing Savory Baked Chicken Side Dishes, 35 Baked Apricot Tzimmes Apple Matzah Kugel Matzo Kugel Matzah Kugel Springtime Kugel Passover Apple-Cinnamon Farfel Kugel Mina Asparagus Nicoise Desserts, 47 Passover Mousse Chocolate-Macaroon Tart Coconut Macaroons Lemon Squares Rocky Road Cookies & Snacks, 54 Chewy Meringue Cookies Farfel-Almond Cookies Peanut Butter Cookies Pignoli Cookies Mini-Morsel Meringue Cookies Cinnamon Snack Bars Matzo Toffee Passover GranolA Apple Pie Passover Brittle Lemon Puffs Breakfast & Miscellaneous, 69 Spinach Frittata Kugel Muffins Passover Vegetable Muffins Matzot, Egg & Cottage Cheese Custard Green Chile Matzah Quiche Chocolate Dipped Potato Chips Charoset & Appetizers 11 Classic Charoset By Mona Davis Ingredients: 3 medium apples, such as Fuji or Honeycrisp, peeled and finely diced 1c. toasted walnuts, roughly chopped 1/4 c. golden raisins 1/4 c. sweet red wine, such as Manischewitz 1/2 tbsp. -

Gender, Acculturation, and American Jewish Cookbooks: 1870S-1930S

Becoming American in the Kitchen: Gender, Acculturation, and American Jewish Cookbooks: 1870s-1930s By Roselyn Bell A thesis submitted to the School of Graduate Studies Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey In partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts Graduate Program in Jewish Studies Written under the direction of Nancy Sinkoff And approved by ________________________ ________________________ ________________________ New Brunswick, New Jersey January 2019 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS: BECOMING AMERICAN IN THE KITCHEN: GENDER, ACCULTURATION, AND AMERICAN JEWISH COOKBOOKS: 1870s-1930s By ROSELYN M. BELL Thesis Director: Dr. Nancy Sinkoff This thesis examines American Jewish cookbooks from the 1870s through the 1930s as artifacts of acculturation—in particular, the acculturation process of Jewish women as distinct from that of Jewish men. These cookbooks are gendered primary documents in that they were written by women and for women, and they reflect messages about women’s place in society coming from the broad American cultural climate and from Jewish sources. In serving charitable ends, the cookbooks mirror the American Protestant notion that women’s spirituality is expressed through good deeds of philanthropy. They also reveal lessons about health and hygiene directed at new immigrants to make them and their children accepted in mainstream society, and fads and fashions of hostessing that were being imitated by Jewish women. These elements of “becoming American” were more significant in the acculturation process of Jewish women than of Jewish men. ii Cookbooks, particularly those of the fund-raising charitable variety, were instruments for building women’s sense of community. Through community cookbooks, women in the sisterhoods of synagogues as well as in other philanthropic groups could assert control over a portion of the budget of the synagogue or charitable institution. -

Januaryfebruarybulletin2017.Pdf

Bulletin January/February 2017 Volume 64 Issue 4 Shabbat Services: Friday, January 6 Shabbat Hallelu 7:45 PM From the Desk of Rabbi Sagal Vayigash Saturday, January 7 Shabbat Minyan 9:45 AM Announcing Fourth Friday! Worship at 6 PM! Friday, January 13 Kehillah Tefillah/Shabbat B’Yachad 6:00 PM Here at Temple Emanu-El, we are constantly attempting to create worship services that are meaningful, Erev Shabbat Service w/Choir 7:45 PM deeply spiritual, joyful, and spirited. Saturday, January 14 Vayechi Simchat Shabbat 9:00 AM Traditionally, Shabbat evening services began at sundown and then the family would gather for Shabbat Shabbat Minyan 9:45 AM dinner. In the 1950’s, the practice began of late evening Friday night services, in order to accommodate Friday, January 20 the growing number of Jews who lived in the suburbs and were commuting to and from work. Hence the Zimrat Social Justice Shabbat and services at 8 or 8:30. Presentation of the Gilbert Award 7:45 PM Saturday, January 21 Shemot Reform Jewish communities across North America and Israel, in order to more fully embrace the arc of Tiny Tot Shabbat 9:30 AM Shabbat, are turning to an earlier and more time-honored Friday evening model—consisting of an earlier Shabbat Minyan 9:45 AM start time for services followed by a traditional Shabbat meal in homes and/or the synagogue. Friday, January 27 (note time change) Erev Shabbat Service 6:00 PM At Temple Emanu-El we are excited to begin a “pilot” Fourth Friday of the month Kabbalat Shabbat experience.