My Iranian Sukkah

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369

Mah Tir, Mah Bahman & Asfandarmad 1 Mah Asfandarmad 1369, Fravardin & l FEZAN A IN S I D E T HJ S I S S U E Federation of Zoroastrian • Summer 2000, Tabestal1 1369 YZ • Associations of North America http://www.fezana.org PRESIDENT: Framroze K. Patel 3 Editorial - Pallan R. Ichaporia 9 South Circle, Woodbridge, NJ 07095 (732) 634-8585, (732) 636-5957 (F) 4 From the President - Framroze K. Patel president@ fezana. org 5 FEZANA Update 6 On the North American Scene FEZ ANA 10 Coming Events (World Congress 2000) Jr ([]) UJIR<J~ AIL '14 Interfaith PUBLICATION OF THE FEDERATION OF ZOROASTRIAN ASSOCIATIONS OF '15 Around the World NORTH AMERICA 20 A Millennium Gift - Four New Agiaries in Mumbai CHAIRPERSON: Khorshed Jungalwala Rohinton M. Rivetna 53 Firecut Lane, Sudbury, MA 01776 Cover Story: (978) 443-6858, (978) 440-8370 (F) 22 kayj@ ziplink.net Honoring our Past: History of Iran, from Legendary Times EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Roshan Rivetna 5750 S. Jackson St. Hinsdale, IL 60521 through the Sasanian Empire (630) 325-5383, (630) 734-1579 (F) Guest Editor Pallan R. Ichaporia ri vetna@ lucent. com 23 A Place in World History MILESTONES/ ANNOUNCEMENTS Roshan Rivetna with Pallan R. Ichaporia Mahrukh Motafram 33 Legendary History of the Peshdadians - Pallan R. Ichaporia 2390 Chanticleer, Brookfield, WI 53045 (414) 821-5296, [email protected] 35 Jamshid, History or Myth? - Pen1in J. Mist1y EDITORS 37 The Kayanian Dynasty - Pallan R. Ichaporia Adel Engineer, Dolly Malva, Jamshed Udvadia 40 The Persian Empire of the Achaemenians Pallan R. Ichaporia YOUTHFULLY SPEAKING: Nenshad Bardoliwalla 47 The Parthian Empire - Rashna P. -

Leket-Israel-Passove

Leave No Crumb Behind: Leket Israel’s Cookbook for Passover & More Passover Recipes from Leket Israel Serving as the country’s National Food Bank and largest food rescue network, Leket Israel works to alleviate the problem of nutritional insecurity among Israel’s poor. With the help of over 47,000 annual volunteers, Leket Israel rescues and delivers more than 2.2 million hot meals and 30.8 million pounds of fresh produce and perishable goods to underprivileged children, families and the elderly. This nutritious and healthy food, that would have otherwise gone to waste, is redistributed to Leket’s 200 nonprofit partner organizations caring for the needy, reaching 175,000+ people each week. In order to raise awareness about food waste in Israel and Leket Israel’s solution of food rescue, we have compiled this cookbook with the help of leading food experts and chefs from Israel, the UK , North America and Australia. This book is our gift to you in appreciation for your support throughout the year. It is thanks to your generosity that Leket Israel is able to continue to rescue surplus fresh nutritious food to distribute to Israelis who need it most. Would you like to learn more about the problem of food waste? Follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter or visit our website (www.leket.org/en). Together, we will raise awareness, continue to rescue nutritious food, and make this Passover a better one for thousands of Israeli families. Happy Holiday and as we say in Israel – Beteavon! Table of Contents Starters 4 Apple Beet Charoset 5 Mina -

Crispy Ricotta Pierogi with Warm Apple-Cabbage Salad & Browned Butter

Crispy Ricotta Pierogi with Warm Apple-Cabbage Salad & Browned Butter With this dish, we’re welcoming in the season by preparing one of our favorite comfort foods— pierogi. The national dish of Poland, these stuffed dumplings have been enjoyed since the 13th Century. To save time without sacrificing flavor, we’re using pre-made dumpling wrappers, and crimping the dough around a delicious filling of ricotta cheese and classic spices. Smothered in nutty browned butter and served with a warm salad of sweet apple, aromatic fennel and hearty cabbage, these crispy pierogi make for the perfect early-autumn dinner. Ingredients 12 Dumpling Wrappers 1 Cup Part-Skim Ricotta Cheese 1 Apple 1 Baby Fennel Bulb ¾ Pound Cabbage Knick Knacks 2 Tablespoons Butter 2 Tablespoons Champagne Vinegar ⅓ Cup Sour Cream 2 Teaspoons Pierogi Spice Blend (Poppy Seeds, White Granulated Sugar, Ground Nutmeg & Whole Dried Caraway Seeds) Makes 2 Servings About 700 Calories Per Serving Prep Time: 10 min | Cook Time: 25 to 35 min For cooking tips & tablet view, visit blueapron.com/recipes/725 Recipe #725 Instructions For cooking tips & tablet view, visit blueapron.com/recipes/725 1 2 Prepare the ingredients: Form the pierogi: Wash and dry the fresh produce. Remove the dumpling wrappers To make the filling, in a medium bowl, combine the cheese and from their package and stack on a plate; cover with a damp paper half the spice blend; season with salt and pepper to taste. Fill a towel. Pick off and reserve some of the fennel fronds (the green, small bowl with lukewarm water. Lay the dumpling wrappers on a thread-like tops of the plant); cut off and discard the fennel stems. -

CATERING MENU for PRINTING V2 05232019

CATERING ACCESSORIES (Free for Order over $800)加热餐具 (Will be automatically included in the total order for best dining experience. Please let us know if you do not need it and we are happy to accommodate.) Chafer Set to Keep Your Food Warm $12 per set (Each set can hold 2 hot dishes) CATERING MENU READY TO ORDER? (Please let us know if your party准备好订餐了? have any food allergies before placing your order) To place orders and price inquries, please email us : [email protected] Cancellation Policy: Requires 48 hours’ notice, otherwise a 50% cancellation fee will apply Delivery/Handling Fee: $30 (NYC) www.yasotangbao.com Our Website: FIRST ORDER 10% OFF 第一次订餐 PROTEINS YASO CATERING 主菜 Pick a Set, Order a La Carte, or Mix and Match (Minimum $125) A La Carte (Ideal for 10) Braised Beef Shank 红烧牛肉 Braised Pork Meatballs 红烧狮子头 Spicy Diced Chicken 辣鸡肉丁 THE BASIC Sweet and Sour Pork Ribs 基础套餐 糖醋小排 Braised Tofu (V) 红烧豆腐 Small 1 Protein, 1 Side, 1 Egg, 1 Rice Ideal for 10 Drunken Chicken (Cold Dish) 绍兴醉鸡 Medium 2 Proteins, 2 Sides, 2 Eggs, 2 Rice Ideal for 20 Large 3 Proteins, 3 Sides, 3 Eggs, 3 Rice Ideal for 30 SIDES 配菜 A La Carte (Ideal for 10) Garlic Cucumber Salad (V) THE CLASSIC (BEST VALUE) 蒜蓉黄瓜 经典套餐(最超值) Garden Vegetable (V) 时蔬 Soy Glazed Egg Small 1 Dumpling, 1 Protein, 1 Side, 1 Egg, 1 Rice Ideal for 10 卤蛋 Soy Garlic Fried Noodle (V) Medium 2 Dumplings, 2 Proteins, 2 Sides, 2 Eggs, 2 Rice Ideal for 20 蒜香炒面 Soy Garlic Fried Rice (V) Large 3 Dumplings, 3 Proteins, 3 Sides, 3 Eggs, 3 Rice Ideal for 30 蒜香炒饭 White Rice 白饭 DUMPLINGS DRINKS 点心 饮品 A La Carte (20 pieces, with exceptions) Bruce Cost Ginger Ale 生姜汽水 Assorted YEO'S Canned Asian Beverage Steamed Baos (3 choices of fillings: Pork, Curry Chicken, Vegetable) 各式杨协成罐装饮料 蒸包 (Soy Milk , Chrysanthemum Tea , Green Tea , 豆浆 菊花茶 绿茶 Pan Fried Baos (3 choices of fillings: Pork, Curry Chicken, Vegetable) Iced Lemon Tea , Lychee Tea ) 煎包 柠檬茶 荔枝茶 Sweet and Spicy Pork Dumpling Jiaozi FIJI Water 甜辣猪肉饺子 斐济矿泉水 S.Pellegrino Sparkling Water 圣培露气泡水 . -

Chanukah Cooking with Chef Michael Solomonov of the World

Non-Profit Org. U.S. POSTAGE PAID Pittsfield, MA Berkshire Permit No. 19 JEWISHA publication of the Jewish Federation of the Berkshires, serving V the Berkshires and surrounding ICE NY, CT and VT Vol. 28, No. 9 Kislev/Tevet 5781 November 23 to December 31, 2020 jewishberkshires.org Chanukah Cooking with Chef The Gifts of Chanukah Michael Solomonov of the May being more in each other’s presence be among World-Famous Restaurant Zahav our holiday presents On Wednesday, December 2 at 8 p.m., join Michael Solomonov, execu- tive chef and co-owner of Zahav – 2019 James Beard Foundation award winner for Outstanding Restaurant – to learn to make Apple Shrub, Abe Fisher’s Potato Latkes, Roman Artichokes with Arugula and Olive Oil, Poached Salmon, and Sfenj with Cinnamon and Sugar. Register for this live virtual event at www.tinyurl.com/FedCooks. The event link, password, recipes, and ingredient list will be sent before the event. Chef Michael Solomonov was born in G’nai Yehuda, Israel, and raised in Pittsburgh. At the age of 18, he returned to Israel with no Hebrew language skills, taking the only job he could get – working in a bakery – and his culinary career was born. Chef Solomonov is a beloved cham- pion of Israel’s extraordinarily diverse and vibrant culinary landscape. Chef Michael Solomonov Along with Zahav in Philadelphia, Solomonov’s village of restaurants include Federal Donuts, Dizengoff, Abe Inside Fisher, and Goldie. In July of 2019, Solomonov brought BJV Voluntary Subscriptions at an another significant slice of Israeli food All-Time High! .............................................2 culture to Philadelphia with K’Far, an Distanced Holidays? Been There, Israeli bakery and café. -

Considerations About Semitic Etyma in De Vaan's Latin Etymological Dictionary

applyparastyle “fig//caption/p[1]” parastyle “FigCapt” Philology, vol. 4/2018/2019, pp. 35–156 © 2019 Ephraim Nissan - DOI https://doi.org/10.3726/PHIL042019.2 2019 Considerations about Semitic Etyma in de Vaan’s Latin Etymological Dictionary: Terms for Plants, 4 Domestic Animals, Tools or Vessels Ephraim Nissan 00 35 Abstract In this long study, our point of departure is particular entries in Michiel de Vaan’s Latin Etymological Dictionary (2008). We are interested in possibly Semitic etyma. Among 156 the other things, we consider controversies not just concerning individual etymologies, but also concerning approaches. We provide a detailed discussion of names for plants, but we also consider names for domestic animals. 2018/2019 Keywords Latin etymologies, Historical linguistics, Semitic loanwords in antiquity, Botany, Zoonyms, Controversies. Contents Considerations about Semitic Etyma in de Vaan’s 1. Introduction Latin Etymological Dictionary: Terms for Plants, Domestic Animals, Tools or Vessels 35 In his article “Il problema dei semitismi antichi nel latino”, Paolo Martino Ephraim Nissan 35 (1993) at the very beginning lamented the neglect of Semitic etymolo- gies for Archaic and Classical Latin; as opposed to survivals from a sub- strate and to terms of Etruscan, Italic, Greek, Celtic origin, when it comes to loanwords of certain direct Semitic origin in Latin, Martino remarked, such loanwords have been only admitted in a surprisingly exiguous num- ber of cases, when they were not met with outright rejection, as though they merely were fanciful constructs:1 In seguito alle recenti acquisizioni archeologiche ed epigrafiche che hanno documen- tato una densità finora insospettata di contatti tra Semiti (soprattutto Fenici, Aramei e 1 If one thinks what one could come across in the 1890s (see below), fanciful constructs were not a rarity. -

Resale Catalog Dumplings & Potstickers

Resale Catalog Dumplings & Potstickers Chicken & Lemongrass Potsticker: Edamame Dumpling: An Asian potsticker filled with tender A traditional Asian potsticker filled chicken coupled with lemongrass, and with an amalgam of tender soybeans, scallions. cabbage, sweet corn and shiitake mushrooms. - Vegan Item # CO261242 150/case Item # CO261587 150/case Kale & Vegetable Dumpling: Pork Potsticker: An Asian potsticker loaded with kale, A traditional Asian potsticker filled with spinach, corn, tofu, cabbage, carrots, tender pork, cabbage and mushrooms, edamame, onions, and a touch of folded into an authentic wrapper. sesame oil. - Vegan Item # CO261730 150/case Item # CO261365 150/case Vegetable Posticker: Shrimp Dumpling: Traditional Asian potsticker filled with A traditional Asian potsticker filled a blend of cabbage, carrots, tofu, bean with shrimp, and folded in an authentic sprouts, vermicelli, onions, scallions, and dumpling. celery. Item # CO701014 150/case Item # CO242043 150/case Peking Duck Mini Dumpling: Chicken Teriyaki Potsticker: A miniature traditional Asian potsticker A traditional Asian potsticker filled with filled with Peking style duck and an tender chicken and traditional teriyaki amalgam of scallions, cabbage, cilantro sauce. and hoisin sauce and folded into an authentic dumpling. Item # CO261617 150/case Item # CO261259 150/case Bulgogi Beef Dumpling: Pork Kimchi Dumpling: Korean inspired dumpling stuffed with Korean inspired dumpling filled with beef marinated in a traditional Korean savory pork balanced against the bulgogi -

Catering Menu

Catering (Collection only) Minimum order £100 Deluxe falafel platter £115 mezze-salads, dips platter £115 40 Large homemade falafel balls, Israeli Feeds 6 - 8 Hummus, tzatziki, Israeli salad, Tabouli Feeds 6 - 8 salad, hummus, Tabouli salad, Tangy People salad, aubergine & pine nuts salad, People cabbage slaw, pickles & shifka peppers, pickles, olives & shifka peppers, chilli Chilli harissa sauce, tahini sauce harissa sauce, Israeli pita(5), greek & Israeli pita(10) pita(5) Allergens: Cereals(gluten), sesame, soy Allergens: Cereals(gluten), sesame, soy, milk, nuts Extras: Extras: Homemade coleslaw + £15 With tangy cabbage slaw + £15 Char-grilled aubergine & tahini + £30 Char-grilled aubergine & tahini + £30 With homemade tzatziki + £15 With homemade tzatziki + £15 Falafel bar £12 pP Israeli tasting menu £26 pp 15 Person minimum order 15 Person minimum order 4 Large falafel balls per person Falafel bar or mezze platter menu Israeli salad, hummus, Tabouli salad, Tangy + Homemade chicken shawarma cabbage slaw, pickles & shifka peppers, + Chicken shashlik (skewers of chicken thigh/breast) chilli harissa sauce, tahini sauce & + Amba sauce Israeli pita(1 pita per person) + Extra pita PP (Kosher meat available on request at extra cost) Allergens: Cereals(gluten), sesame, soy, milk Allergens: Cereals(gluten), sesame, soy, milk, nuts, celery Extras: With tangy cabbage slaw + £2.00 per person Meat dishes served in aluminium foil containers to be reheated on site With homemade tzatziki + £2.00 per person Extras: Homemade coleslaw + £2.00 per person Other options may be available on request With homemade tzatziki + £2.00 per person Box of falafel balls £20 box of smoky cauliflower £30 box of grilled AUBERGINE £30 25 Homemade large falafel balls, BBQ cauliflower with fresh turmeric, tahini, Char-grilled aubergine with garlic, served with tahini sumac, garlic & herbs oil & squeeze of lemon tahini, harissa oil, pine nuts, fresh green herbs & Zahatar. -

Marion: I Travelled from My Home in Toronto, Canada, to Brooklyn, New York, Because of Gefilte Fish

Marion: I travelled from my home in Toronto, Canada, to Brooklyn, New York, because of gefilte fish. Many Jewish foods are adored and celebrated but gefilte fish isn't one of them. Can two young authors and entrepreneurs restore its reputation? I'm Marion Kane, Food Sleuth®, and welcome to "Sittin' in the Kitchen®". Liz Alpern and Jeffrey Yoskowitz are co-authors of The Gefilte Manifesto and co-owners of The Gefilteria. Their goal is to champion Jewish foods like gefilte fish, give them a tasty makeover and earn them the respect they deserve. I first met Liz when she appeared on a panel at the Toronto Ashkenaz Festival. I knew immediately that I had to have her on my podcast. We talked at her apartment in Crown Heights, Brooklyn. Marion: Let's sit down and talk Ashkenazi food - and gefilte fish in particular. I'm going to ask you to introduce yourselves. Liz: My name's Liz Alpern. I am the co-owner of The Gefilteria and co-author of The Gefilte Manifesto. Jeffrey: My name is Jeffrey Yoskowitz. I am the co-owner and chief pickler of The Gefilteria, and I am a co-author of The Gefilte Manifesto cookbook. Marion: You're both Jewish and Ashkenazi. Liz: Yes, we're both of Eastern European Jewish descent. Marion: Gefilte fish - we have to address this matter. I want to read a description of gefilte fish of the worst kind. Quote, "Bland, intractably beige, and (most unforgivably of all) suspended in jelly, the bottled version seemed to have been fashioned, golem-like, from a combination of packing material and crushed hope." Liz & Jeffrey: (laugh) Marion: That's a very unfavorable review of gefilte fish. -

Cavalier Cooking 101: Dumplings from Around the World

Cavalier Cooking 101: Dumplings from Around the World Chicken Potstickers Filling: 1 lb. of ground chicken Dipping Sauce: 2 tbsp. of soy sauce 2 tbsp. of soy sauce 2 tbsp. of sweet soy sauce 2 tbsp. of sweet soy sauce 2 tbsp. of fish sauce 1 tsp. of sesame oil 1 tsp. of sesame oil 1 tbsp. of brown sugar 1 bunch of sliced scallions Squeeze of lime juice 1 tbsp. of minced garlic 1 tsp. of minced ginger 1 tbsp. of minced ginger 1 tbsp. of corn starch 4 bok choy heads 2 tsp. of Chinese 5 spice Vegetable Oil for frying Salt and Pepper to taste Wonton wrappers Instructions Blanch the bok choy heads for 3-4 minutes. Mince the bok choy and combine with the rest of the ingredients to make filling. *Tip: To taste the filling, microwave a small ball of the filling until cooked (15 seconds) and taste. Add seasonings according to your preferences. Take 1-2 tsp. of your filling and put into the center of your wonton wrapper. Dip your finger in water and moisten the edges. Then fold your potsticker into whatever shape you want! This video shows some traditional ways to fold your dumpling: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aE82VmqPYj4 Coat non-stick pan with vegetable oil and allow oil to heat up for a few minutes. Put potstickers in pot and fry for 3-4 minutes. Put a 1 tbsp. of water into the pan and cover. Allow the potstickers to steam for 2-3 minutes and then take cover off. -

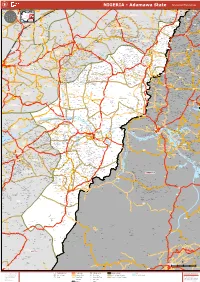

NIGERIA - Adamawa State General Overview

f NIGERIA - Adamawa State General Overview ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Lafiawo Gantsa Mow Sandaouadjiri ! ! Nogagueyguey Suko Bauro ! Joure-Bose Yamtage Loka Fadagwe !Attagara Lumputi !Ngalda ! Dalame ! ! Basle Garin Baruo! Pridang Yard ! ! ! Colare !Dawaluwa ! Tadangara !Agum Charif-Moussari Sabon ! !Bindi Kau Bul ! Halawa Agapalawa Clan ! ! !Munfi Gwano ! Potiskum ! !Two Buruo Sabon Nafada !Nafada ! !Layi Colare Bornu Fadagwe Guduf !Guduku ! ! Tarmoua ! Gari !Gubi ! !Zinkur Gwoza Hyawa ! Djebrili Takomari! Kacalla Fulani ! Bubaya ! ! !Gudoko ! Balaigaje ! ! ! ! Njenam! a ! Ngurunbile ! Lomara Tala Malabrahim ! !Gabai ! !Gawa Tasha ! Gwoza Vredeke ! !Yarbulas NIGER ! !Yelwa Bularaba Dufa Gouedjele ! \! FIKA CHAD ! Kidjimatari Garin GUJBA ! ! ! Wu! rd! bege !Kukwari !Manawaji !Jege Gangawa !Maza !Kotufa Arbokko Clan Gadari !Bukarti ! ! !Nguzowa !Skatikume Je!ngi ! !Korode ! Gabari Jouro-Jallo! !Gumsuri Salakatchi Gargar Gumsuri ! !Guelapar ! ! Jauro Guetam! a !Glovda ! Gashinge !Gole Wakato Daushi Ajir ! ! \! !Ngeltowa ! ! Kunde Talkomari Ganiana ! !Mainya Kaviri-Damboa ! Blamanya !Baba ! Shole Shind! o ! ! Kundulu ! Sherfuri N'Djamena Allagarno Wulade ! ! !Hong Vadagum Hambadga ! Moundongwa ! ! Wakato ! ! Geldavi Karama Koy!aya Abuduski Kunadur Kaviri ! Danga Danga ! Kudu Mondu ! Jouro-Ahmadu ! ! ! ! Manori !Ecole Fulani ! !Clan Tagoshe ! !Goueledje Geldavi ! !Ngurum Gwoza ! ! Vreke! ! ! ! Horogoua ! !Kirshigi Yabal !Gombi ! Kughum Kouyape Yayaro ! ! ! !Mbuga ! ! ! Ka! dubu Garjam Santow Horessa Malougoudje Gadum ! ! GWOZA ! Loghpere Bolari -

Gefilte Fish CARTE

5 SENSES A LA CARTE IDENTITIES Gefilte Fish For many people gelte sh is the epitome of traditional Jewish cooking. It was served on Shabbat and other high holidays in the For about 26 patties: shtetl, the small towns in Eastern Europe shaped by Jewish 7–7 ½ pounds whole carp, whitesh, and culture. Housewives procured a living sh, usually a carp, which pike, lleted and ground* was then killed at home. They cut open the sh’s belly in such a 4 quarts (liter) cold water or to just cover way that they could remove the bones and meat without tearing 3 teaspoons salt or to taste the skin. After mixing the meat of the sh with matzo meal or 3 onions, peeled white bread, they lled the sh skin with the farce. This way, one 4 medium carrots, peeled sh was enough to satisfy the whole hungry family. Since 2 tablespoons sugar cooking is not permitted on Shabbat, the dish was prepared 1 small parsnip, chopped before it began and eaten cold. 3–4 large eggs Even though gelte sh can be found in all varieties of Ashkenazi freshly ground pepper to taste cuisine, there were two distinct ways to prepare it in Eastern ½ cold water Europe, separated by a clear geographical line. In southwest ⅓ cup matza meal Poland, Galicia, and German-speaking regions, people preferred * Have your shmonger grind the sh and ask him to eat their gelte sh sweet. By contrast, the so-called Litvaks, to save and give you the tails, ns, heads, and Jews from Lithuania and other regions under Russian inuence, bones.