Adaptation, Immigration, and Identity: the Tensions of American Jewish Food Culture by Mariauna Moss Honors Thesis History Depa

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kosher Grocery Misc Manischewitz Kosher Potato Starch Manischewitz Kosher Soup/Matzo Ball Mix Real Salt Kosher Sea Salt R.W

Kosher Sugar Bowl Petite Brownie Bites Tumaros Tortillas – Many varieties Grocery Misc Western Bagel – Many varieties Manischewitz Kosher Potato Starch Manischewitz Kosher Soup/Matzo Ball Mix Cereal/Baking Real Salt Kosher Sea Salt Alpen-No Sugar/Salt R.W. Knudsen Kosher Sparkling Concord Grape Juice Alpen-Original Diamond Crystal Pure and Natural Kosher Salt Argo Corn Starch Manischewitz Egg Noodles Arm & Hammer Baking Soda Gefen Honey Bear Arrowhead Baking Mixes – Many varieties Manischewitz Potato Pancake Mix Back To Nature Granola Manischewitz Matzo Meal Bakery OnM.Granola AppleRaisWalnt Kedem Concord Grape Juice Bakery OnM.Granola ExFruit&Nut Kedem Plain Tea Biscuits Bakery OnM.Granola NuttyCranMaple Kedem Vanilla Tea Biscuits Barbaras Cereal – Many varieties Kedem Chocolate Tea Biscuits Carnation Evap.Milk Manischewitz Original Horseradish Sauce Dr. Oetker Mixes – Many varieties Healthy Times Baby Food – Many varieties Eco Planet GF Cereal – Many flavors Newmans Mints – Many varieties EnviroKidz Cereal – Many varieties Stretch Island Mango Erba Dolce Stevia 50pk Stretch Island Raspberry Familia SwissMuesli No Sugar Stretch Island Strawberry Familia SwissMuesli Orig Flavorganics Extract – Many flavors Bakery Florida Cryst.Sugar-Org. Alvarado – Many varieties Ghirardelli Baking Bar Arrowhead Stuffing Herb Ghirardelli Chocolate Chips Bays EnglishMuffin-Orig Ghirar.Cocoa-SweetChoc. Bays EnglishMuffin-Sourdough Ghirar.Cocoa-Unsweetened Food For Life – Many varieties Ghirar.Wht.Chip-Classic Kontos – Many varieties Gold Medal Flour La Tortilla -

Leket-Israel-Passove

Leave No Crumb Behind: Leket Israel’s Cookbook for Passover & More Passover Recipes from Leket Israel Serving as the country’s National Food Bank and largest food rescue network, Leket Israel works to alleviate the problem of nutritional insecurity among Israel’s poor. With the help of over 47,000 annual volunteers, Leket Israel rescues and delivers more than 2.2 million hot meals and 30.8 million pounds of fresh produce and perishable goods to underprivileged children, families and the elderly. This nutritious and healthy food, that would have otherwise gone to waste, is redistributed to Leket’s 200 nonprofit partner organizations caring for the needy, reaching 175,000+ people each week. In order to raise awareness about food waste in Israel and Leket Israel’s solution of food rescue, we have compiled this cookbook with the help of leading food experts and chefs from Israel, the UK , North America and Australia. This book is our gift to you in appreciation for your support throughout the year. It is thanks to your generosity that Leket Israel is able to continue to rescue surplus fresh nutritious food to distribute to Israelis who need it most. Would you like to learn more about the problem of food waste? Follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter or visit our website (www.leket.org/en). Together, we will raise awareness, continue to rescue nutritious food, and make this Passover a better one for thousands of Israeli families. Happy Holiday and as we say in Israel – Beteavon! Table of Contents Starters 4 Apple Beet Charoset 5 Mina -

Comparative Antimicrobial Activity Study of Brassica Oleceracea †

Proceedings Comparative Antimicrobial Activity Study of Brassica oleceracea † Sandeep Waghulde *, Nilofar Abid Khan *, Nilesh Gorde, Mohan Kale, Pravin Naik and Rupali Prashant Yewale Konkan Gyanpeeth Rahul Dharkar College of Pharmacy and Research Institute, Karjat, Dist-Raigad, Pin code 410201, India; [email protected] (N.G.); [email protected] (M.K.); [email protected] (P.N.); [email protected] (R.P.Y.) * Correspondence: [email protected] (S.W.); [email protected] (N.A.K.) † Presented at the 22nd International Electronic Conference on Synthetic Organic Chemistry, 15 November– 15 December 2018. Available Online: https://sciforum.net/conference/ecsoc-22. Published: 14 November 2018 Abstract: Medicinal plants are in rich source of antimicrobial agents. The present study was carried out to evaluate the antimicrobial effect of plants from the same species as Brassica oleceracea namely, white cabbage and red cabbage. The preliminary phytochemical analysis was tested by using a different extract of these plants for the presence of various secondary metabolites like alkaloids, flavonoids, tannins, saponins, terpenoids, glycosides, steroids, carbohydrates, and amino acids. The in vitro antimicrobial activity was screened against clinical isolates viz gram positive bacteria Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pyogenes, gram negative bacteria Escherichia coli, Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Extracts found significant inhibition against all the pathogens. Keywords: plant extract; phytochemicals; antibacterial activity; antifungal activity 1. Introduction Despite great progress in the development of medicines, infectious diseases caused by bacteria, fungi, viruses and parasites are still a major threat to public health. The impact is mainly observed in developing countries due to relative unavailability of medicines and the emergence of widespread drug resistance [1]. -

The Mineral Waters of Europe

ffti '.>\V‘ :: T -T'Tnt r TICEB9S5S & ;v~. >Vvv\\\\\vSVW<A\\vvVvi% V\\\WvVA ^.« .\v>V>»wv> ft ‘ai^trq I : ; ; THE MINERAL WATERS OF EUROPE: INCLUDING T DESCRIPTION OF ARTIFICIAL MINERAL WATERS. BY TICHBORNE, LL.D, F.C.S., M.R.I.A., Fellow of the Institute of Chemistry of Great Britain and Ireland ; Professor of Chemistry at the Carmichael College of Medicine, Dublin; Late Examiner in Chemistry in the University of Dublin; Professor of Chemistry, Apothecaries' Hall of Ireland ; President of the Pharmaceutical Society of Ireland Honorany and Corresponding Member of the Philadelphia and Chicago Colleges of Pharmacy ; Member of the Royal Geological Society of Ireland Analyst to the County of Longford ; £c., £c. AND PROSSER JAMES, M.D., M.R.C.P., Lecturer on Materia Medica and Therapeutics at the London Hospital; Physician to the Hospital for Diseases of the Throat and Chest ; Late Physician to the North London Consumption Hospital; Ac., tCc., &c. LONDON BAILLIERE, TINDALL & COX. 1883. Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2015 https://archive.org/details/b21939032 PREFACE. Most of the objects had in view in writing the present work have been incidentally mentioned in the Introductory Chapter. It may, however, be desiderable to enumerate concisely the chief points which have actuated the authors in penning the “ Mineral Waters of Europe.” The book is intended as a reliable work of reference in connection with the chief mineral waters, and also to give the character and locality of such other waters as are in use. In many of the books published upon the subject the analyses given do not represent the present com- position of the waters. -

YOM KIPPUR 2015 YOM KIPPUR 2015 * New Item V Vegetarian N Contains Nuts GF Gluten Free

YOM KIPPUR 2015 YOM KIPPUR 2015 * New Item V Vegetarian N Contains Nuts GF Gluten Free THE “BREAK THE FAST” PACKAGE No substitutions or deletions. In disposable containers except where noted. Package orders are available for 10 or more people in multiples of 5 thereafter. All “choice” items may be divided in multiples of 10 only. ALL PACKAGES INCLUDE Traditional creamy white albacore tuna salad. GF Nancy’s Noodle Kugel with corn flake and cinnamon topping. May also be ordered without raisins. V Fresh sliced fruit. V | GF SELECT A BASKET THE BEST SMOKED FISH BASKET 28.95/pp New York’s finest nova smoked salmon. Rolled. GF Smoked whitefish filet and peppered sable. Taster portion. GF Freshly baked assortment of “New York” bagels and bialys. 2 per person. Whipped plain and chive cream cheese. GF Sliced muenster, cheddar and swiss. Sliced tomato, shaved bermuda onion, seedless cucumber and mediterranean black olives. GF or NOVA LOX BASKET The Best Smoked Fish Basket without the smoked whitefish and peppered sable. 23.75/pp New York’s finest nova smoked salmon. Rolled. GF Freshly baked assortment of “New York” bagels and bialys. 2 per person. Whipped plain and chive cream cheese. GF Sliced muenster, cheddar and swiss. Sliced tomato, shaved bermuda onion, seedless cucumber and mediterranean black olives. GF or DELI BASKET 27.95/pp Eisenberg first-cut corned beef (50%), oven roasted turkey breast (30%), and sirloin (20%). Sliced cheddar and swiss cheese. Lettuce, tomato, pickle, red onion and black olives, mustard and mayonnaise. Freshly baked french onion rolls, old fashioned rolls, and light and dark rye. -

A Taste of Teaneck

.."' Ill • Ill INTRODUCTION In honor of our centennial year by Dorothy Belle Pollack A cookbook is presented here We offer you this recipe book Pl Whether or not you know how to cook Well, here we are, with recipes! Some are simple some are not Have fun; enjoy! We aim to please. Some are cold and some are hot If you love to eat or want to diet We've gathered for you many a dish, The least you can do, my dears, is try it. - From meats and veggies to salads and fish. Lillian D. Krugman - And you will find a true variety; - So cook and eat unto satiety! - - - Printed in U.S.A. by flarecorp. 2884 nostrand avenue • brooklyn, new york 11229 (718) 258-8860 Fax (718) 252-5568 • • SUBSTITUTIONS AND EQUIVALENTS When A Recipe Calls For You Will Need 2 Tbsps. fat 1 oz. 1 cup fat 112 lb. - 2 cups fat 1 lb. 2 cups or 4 sticks butter 1 lb. 2 cups cottage cheese 1 lb. 2 cups whipped cream 1 cup heavy sweet cream 3 cups whipped cream 1 cup evaporated milk - 4 cups shredded American Cheese 1 lb. Table 1 cup crumbled Blue cheese V4 lb. 1 cup egg whites 8-10 whites of 1 cup egg yolks 12-14 yolks - 2 cups sugar 1 lb. Contents 21/2 cups packed brown sugar 1 lb. 3112" cups powdered sugar 1 lb. 4 cups sifted-all purpose flour 1 lb. 4112 cups sifted cake flour 1 lb. - Appetizers ..... .... 1 3% cups unsifted whole wheat flour 1 lb. -

Cholent Available Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday Schnitzel Marinated in a Barbecue Sauce with a Bissli Coating Half Lb

Specials All sides are half-pound per portion; does not include grilled vegetables and special salads. Lunch (12:30pm - 4:00pm) Choice of any chicken main with two sides and a small fountain drink Yap-Chicken Bar $6.99 TOPPINGS: Cole Slaw, Sauerkraut, Pickle Chips, Israeli Pickles, Sour Pickles, Hot Banana Peppers, Jalapeno Dinner Peppers, Sweet Peppers, Sweet Relish, Fried Onions, Diced Onions, Red Onions, Chummus, Choice of two chicken mains, two sides, Romaine Lettuce, Iceberg Lettuce, Tomatoes, Cucumbers, Green Olives, Black Olives, Sauteed and two small fountain drinks Mushrooms, Sliced Eggs, Fried Eggplant $13.99 SauCeS: Ketchup, Mustard, Deli Mustard, Spicy Deli Mustard, Honey Mustard, Mayo, Garlic Mayo, Spicy Mayo, Russian Dressing, Pesto, Chimichurri, Sweet Chili Sauce, Barbecue Sauce, Creamy Choice of four chicken mains and four sides Dijonnaise, Buffalo Sauce, Spicy Jalapeno Sauce, Some of This (hot & spicy), Some of That (sweet & spicy) $24.49 SeRVeD Choice of eight chicken mains, eight sides and one salad on a crispy baguette (regular or whole wheat) w/ choice of toppings from our bar. $49.99 Good Old Fashioned Barbecue and Bissli Cholent Available Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday Schnitzel Marinated in a barbecue sauce with a Bissli coating Half lb. ....... $2.99 1 lb. ............ $5.99 2 lb. ........... $9.99 Yitzy’s Sweet Style Marinated in a sweet tangy sauce Israeli Style Schnitzel with a crunchy cornflake coating With a Mediterranean spice Cholent Special 1 lb cholent, kishka, overnight potato kugel, & small fountain -

Detailed Instructions of the Electric Pyrolytic Oven

GB IE MT DETAILED INSTRUCTIONS OF THE ELECTRIC PYROLYTIC OVEN www.gorenje.com We thank you for your trust in purchasing our appliance. This detailed instruction manual is supplied to allow you to learn about your new appliance as quickly as possible. Make sure you have received an undamaged appliance. Should you notice any transport damage, please notify your dealer or regional warehouse where your appliance was supplied from. The telephone number can be found on the invoice or on the delivery note. Instructions for installation and connection are supplied on a separate sheet. Instructions for use are also available at our website: www.gorenje.com / < http://www. gorenje.com /> Important information Tip, note CONTENTS WARNINGS 4 IMPORTANT SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS 6 Before connecting the appliance 7 THE ELECTRIC PYROLYTIC OVEN INTRODUCTION 10 Control unit 12 Information on the appliance - data plate (depending on the model) 13 BEFORE THE FIRST USE INITIAL PREPARATION OF THE 14 FIRST USE APPLIANCE 15 SELECTING THE MAIN MENUS FOR BAKING AND SETTINGS SETTINGS AND BAKING 16 A) Baking by selecting the type of food (automatic mode auto) 18 B) Baking by selecting the mode of operation (professional (pro) mode) 24 C) Storing your own programme (my mode) 25 START OF BAKING 25 END OF BAKING AND OVEN SHUT-OFF 26 SELECTING ADDITIONAL FEATURES 28 SELECTING GENERAL SETTINGS 30 DESCRIPTIONS OF SYSTEMS (COOKING MODES) AND COOKING TABLES 45 MAINTENANCE & CLEANING CLEANING AND MAINTENANCE 46 Conventional oven cleaning 47 Automatic oven cleaning – pyrolysis 49 Aqua clean cleaning program 50 Removing and cleaning wire and telescopic extendible guides 51 Removing and inserting the oven door 53 Removing and inserting the oven door glass pane 54 Replacing the bulb PROBLEM 55 TROUBLESHOOTING TABLE SOLVING 56 DISPOSAL 697193 3 IMPORTANT SAFETY INSTRUCTIONS CAREFULLY READ THE INSTRUCTIONS AND SAVE THEM FOR FUTURE REFERENCE. -

Kohlrabi, Be Sure It Your Money Stays Locally and Is Is No Larger Than 2 1/2” in Diameter, Recirculated in Your Community

Selection Why Buy Local? When selecting kohlrabi, be sure it Your money stays locally and is is no larger than 2 1/2” in diameter, recirculated in your community. with the greens still attached. Fresh fruits and vegetables are The greens should be deep green more flavorful, more nutritious all over with no yellow spots. and keeps more of its vitamins and Yellow leaves are an indicator that minerals than processed foods. the kohlrabi is no longer fresh. You are keeping farmers farming, which protects productive farmland from urban sprawl and being developed. What you spend supports the family farms who are your neighbors. Care and Storage Always wash your hands for 20 seconds with warm water and soap before and after preparing produce. Wash all produce before eating, FOR MORE INFORMATION... cutting, or cooking. Contact your local Extension office: Kohlrabi can be kept for up to a month in the refrigerator. Polk County UW-Extension Drying produce with a clean 100 Polk County Plaza, Suite 190 cloth or paper towel will further Balsam Lake, WI 54810 help to reduce bacteria that may (715)485-8600 be present. http://polk.uwex.edu Keep produce and meats away Kohlrabi from each other in the refrigerator. Originally developed by: Jennifer Blazek, UW Extension Polk County, Balsam Lake, WI; Colinabo http://polk.uwex.edu (June, 2014) Uses Try It! Kohlrabi is good steamed, Kohlrabi Sauté barbecued or stir-fried. It can also be used raw by chopping and INGREDIENTS putting into salads, or use grated or 4 Medium kohlrabi diced in a salad. -

Over 100 More Deals on Our Shelves! Not All Sales Items Are Listed

Sales list 3/13 - 4/2 Bulk Department Product Name Size Sale Coupons Bulk Organic Green Lentils Per Pound 1.99 Bulk Organic Hulled Millet Per Pound 1.19 Equal Exchange Select Organic Coffee Per Pound 8.99 Fantastic Foods Falafel Mix Per Pound 3.39 Fantastic Foods Hummus Mix Per Pound 4.39 Fantastic Foods Instant Black Beans Per Pound 4.39 Fantastic Foods Instant Refried Beans Per Pound 4.39 Fantastic Foods Vegetarian Chili Mix Per Pound 4.39 Grandy Oats Coconut Granola Per Pound 8.99 Woodstock Dark Chocolate Almonds Per Pound 11.69 Refrigerated Product Name Size Sale Coupons Brown Cow Cream Top Yogurt 5.3-6 oz 4/$3 Earth Balance Buttery Sticks, Original and Soy-Free 16 oz 3.69 Earth Balance Natural Buttery Spread 15 oz 3.69 Earth Balance Organic Whipped Buttery Spread 13 oz 3.69 Earth Balance Organic Coconut Spread 10 oz 3.69 Earth Balance Soy-Free Buttery Spread 15 oz 3.69 Earth Balance Omega-3 Spread 13 oz 3.69 Field Roast Celebration Roast 2 lb 12.99 Field Roast Celebration Roast 1 lb 5.99 Field Roast Hazelnut-Cranberry Stuffed Roast 2 lb 16.99 Florida’s Natural Orange Juice 59 oz 3.69 Follow Your Heart Vegan Egg Powder 4 oz 5.99 Green Valley Organics Lactose-Free Yogurt 24 oz 3.99 Green Valley Organics Lactose-Free Cream Cheese 8 oz 2.99 Hail Merry Macaroon Bites 3.5 oz 2.69 Hail Merry Miracle Tarts 3 oz 2.99 Harmless Harvest Organic Raw Coconut Water 16 oz 3.99 Harmless Harvest Organic Raw Coconut Water 32 oz 7.99 Immaculate Baking Company Flaky Biscuits 16 oz 2/$5 Immaculate Baking Company Cinnamon Rolls 17.5 oz 3.69 Immaculate -

Nybb Togo Menu 2019.Indd

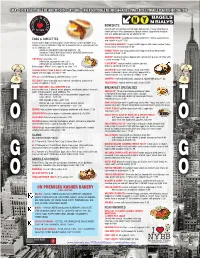

BENEDICTS Served with two gently poached eggs, housemade cheesy hollandaise & choice of home fries, tomatoes or cottage cheese. Upgrade to seasonal fruit or a potato pancake for an additional .99 SOUTHWESTERN* jalapeño bialy topped with beef chorizo, queso fresco EGGS & OMELETTES and chipotle drizzle 11.99 Served with a bagel or bialy & plain cream cheese. Choice of home fries, cottage cheese or tomatoes. Upgrade to seasonal fruit or a potato pancake CALIFORNIA BENEDICT* English muffin topped with house roasted turkey for an additional .99 breast, bacon and avocado 12.49 substitute EGG WHITES OR EGG BEATERS® .99 HUMBLE HASH* two crisp potato latkes topped with our housemade substitute TURKEY BACON or TURKEY SAUSAGE for breakfast corned beef hash 13.49 meat at no additional charge. REUBEN* toasted rye bread topped with corned beef & kraut, drizzled with TWO EGGS* any style. 7.49 russian dressing 12.49 with bacon, sausage or ham. 9.99 with brisket or corned beef hash. 10.49 FLORENTINE* toasted challah, sautéed spinach, Extra hungry? Make it three eggs for an extra 1.49 onions & sprinkled with feta 11.99 CHICKEN FRIED STEAK & EGGS* with home fries, smothered in gravy COLORADO* warm flour tortillas, steak and refried topped with two eggs any style 12.99 beans smothered in green chili gravy, topped with a chipotle drizzle and a sprinkle of cheddar 13.99 LEO Lox, scrambled eggs & sautéed onions. 12.99 COUNTRY* fresh baked biscuits, sausage & housemade gravy 11.99 DELI EGGS* three eggs with your choice of corned beef, pastrami or salami scrambled -

Morphological Characterisation of White Head Cabbage (Brassica Oleracea Var. Capitata Subvar. Alba) Genotypes in Turkey

NewBalkaya Zealand et al.—Morphological Journal of Crop and characterisation Horticultural ofScience, white head2005, cabbage Vol. 33: 333–341 333 0014–0671/05/3304–0333 © The Royal Society of New Zealand 2005 Morphological characterisation of white head cabbage (Brassica oleracea var. capitata subvar. alba) genotypes in Turkey AHMET BALKAYA Keywords cabbage; classification; morphological Department of Horticulture variation; Brassica oleracea; Turkey Faculty of Agriculture University of Ondokuz Mayis Samsun, Turkey INTRODUCTION email: [email protected] Brassica oleracea L. is an important vegetable crop RUHSAR YANMAZ species which includes fully cross-fertile cultivars or Department of Horticulture form groups with widely differing morphological Faculty of Agriculture characteristics (cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower, University of Ankara collards, Brussel sprouts, kohlrabi, and kale). His- Ankara, Turkey torical evidence indicates that modern head cabbage email: [email protected] cultivars are descended from wild non-heading brassicas originating from the eastern Mediterranean AYDIN APAYDIN and Asia Minor (Dickson & Wallace 1986). It is HAYATI KAR commonly accepted that the origin of cabbage is the Black Sea Agricultural Research Institute north European countries and the Baltic Sea coast Samsun, Turkey (Monteiro & Lunn 1998), and the Mediterranean region (Vural et al. 2000). Zhukovsky considered that the origin of the white head cabbage was the Van Abstract Crops belonging to the Brassica genus region in Anatolia and that the greatest cabbages of are widely grown in Turkey. Cabbages are one of the the world were grown in this region (Bayraktar 1976; most important Brassica vegetable crops in Turkey. Günay 1984). The aim of this study was to determine similarities In Turkey, there are local cultivars of cabbage (B.