Summary of the Verdict and Sentence in the Al Mahdi Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

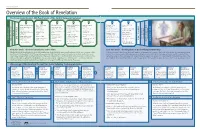

Overview of the Book of Revelation the Seven Seals (Seven 1,000-Year Periods of the Earth’S Temporal Existence)

NEW TESTAMENT Overview of the Book of Revelation The Seven Seals (Seven 1,000-Year Periods of the Earth’s Temporal Existence) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Adam’s ministry began City of Enoch was Abraham’s ministry Israel was divided into John the Baptist’s Renaissance and Destruction of the translated two kingdoms ministry Reformation wicked Wickedness began to Isaac, Jacob, and spread Noah’s ministry twelve tribes of Israel Isaiah’s ministry Christ’s ministry Industrial Revolution Christ comes to reign as King of kings Repentance was Great Flood— Israel’s bondage in Ten tribes were taken Church was Joseph Smith’s ministry taught by prophets and mankind began Egypt captive established Earth receives Restored Church patriarchs again paradisiacal glory Moses’s ministry Judah was taken The Savior’s atoning becomes global CREATION Adam gathered and Tower of Babel captive, and temple sacrifice Satan is bound Conquest of land of Saints prepare for Christ EARTH’S DAY OF DAY EARTH’S blessed his children was destroyed OF DAY EARTH’S PROBATION ENDS PROBATION PROBATION ENDS PROBATION ETERNAL REWARD FALL OF ADAM FALL Jaredites traveled to Canaan Gospel was taken to Millennial era of peace ETERNAL REWARD ETERNITIES PAST Great calamities Great calamities FINAL JUDGMENT FINAL JUDGMENT PREMORTAL EXISTENCE PREMORTAL Adam died promised land Jews returned to the Gentiles and love and love ETERNITIES FUTURE Israelites began to ETERNITIES FUTURE ALL PEOPLE RECEIVE THEIR Jerusalem Zion established ALL PEOPLE RECEIVE THEIR Enoch’s ministry have kings Great Apostasy and Earth -

A Re-Examination of the Millennium in Rev 20:1–6: Consummation and Recapitulation

JETS 44/2 (June 2001) 237–51 A RE-EXAMINATION OF THE MILLENNIUM IN REV 20:1–6: CONSUMMATION AND RECAPITULATION dave mathewson* i. introduction The question of the so-called millennial kingdom in Rev 20:1–6 continues to be a source of fascination in evangelical discussion and dialogue.1 The purpose of this article is to re-examine the question of the millennial king- dom as articulated in Rev 20:1–6. More specifically, this article will consider the meaning and function of 20:1–6 within Revelation as it relates to the contemporary debate about whether this section is best understood within a premillennial or amillennial framework. Hermeneutically, most of the de- bate has centered around how literally the reference to the one thousand years in 20:1–6 should be taken and, more importantly, the relationship be- tween 20:1–6 and 19:11–21. Does the thousand year period in 20:1–6 re- fer to a more or less literal period of time?2 Or should it be understood more symbolically? Does 20:1–6 follow 19:11–21 chronologically, with the one thou- sand years featuring a Zwischenreich (premillennialism), or does the final battle in 20:7–10 recapitulate the battle in 19:11–21, with the reference to the one thousand years in 20:1–6 extending all the way back to the first coming of Christ (amillennialism)?3 * Dave Mathewson is instructor in New Testament at Oak Hills Christian College, 1600 Oak Hills Road SW, Bemidji, MN 56601. 1 Cf. R. -

Lesson 7A FINAL (GENERAL Or LAST) JUDGMENT

Lesson 7A FINAL (GENERAL or LAST) JUDGMENT Beloved Father of Mercy and Justice, We Your children, offer our lives as a pure and holy sacrifice, uniting our lives and our death to the life and death of Your Son and our Savior. At the Final Judgment we will stand united with the Body of Christ, body and soul, to receive Your Son's judgment. We will face this last and definitive judgment unafraid as the Books of Works are opened to reveal the imperishable deeds of love and mercy accumulated by the Church. This is the treasure stored up for eternity which Your children offer in the name of Christ our Savior and Redeemer. Send Your Holy Spirit, Lord, to lead us in this lesson of our study on the Eight Last Things. We pray in the name of God the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Amen. + + + While I was watching thrones were set in place and one most venerable took his seat. His robe was white as snow, the hair of his head as pure as wool. His throne was a blaze of flames; its wheels were a burning fire. A stream of fire poured out, issuing from his presence. A thousand thousand waited on him, ten thousand times ten thousand stood before him. The court was in session and the books lay open. Daniel 7:9-10 For as the Father has life in himself, so he has granted the Son also to have life in himself; and, because he is the Son of man, has granted him power to give judgment. -

Amillennialism Reconsidered Beatrices

Andrews University Seminary Studies, Vol. 43, No. 1,185-210. Copyright 0 2005 Andrews University Press. AMILLENNIALISM RECONSIDERED BEATRICES. NEALL Union College Lincoln, Nebraska Introduction G. K. Beale's latest commentary on Revelation and Kim Riddlebarger's new book A Casefor Ami~~ennialismhave renewed interest in the debate on the nature of the millennium.' Amillennialism has an illustrious history of support from Augustine, theologians of the Calvinistic and ~utheran confessions, and a long line of Reformed theologians such as Abraham Kuyper, Amin Vos, H. Ridderbos, A. A. Hoekema, and M. G. line? Amillennialists recognize that a straightforward reading of the text seems to show "the chronologicalp'ogression of Rev 19-20, the futurity of Satan's imprisonment,the physicality of 'the first resurrection' and the literalness of the one thousand years" (emphasis supplied).) However, they do not accept a chronologicalprogression of the events in these chapters, preferring instead to understand the events as recapitulatory. Their rejection of the natural reading of the text is driven by a hermeneutic of strong inaugurated eschatology4-the paradox that in the Apocalypse divine victory over the dragon and the reign of Christ and his church over this present evil world consist in participating with Christ in his sufferings and death? Inaugurated eschatology emphasizes Jesus' victory over the powers of evil at the cross. Since that monumental event, described so dramatically in Rev 12, Satan has been bound and the saints have been reigning (Rev 20). From the strong connection between the two chapters (see Table 1 below) they infer that Rev 20 recapitulates Rev 12. -

Approaches to Medieval Cultures of Eschatology

Veronika Wieser and Vincent Eltschinger Introduction: Approaches to Medieval Cultures of Eschatology 1. Medieval Apocalypticism and Eschatology In all religions, ideas about the past, the present and the future were shaped and made meaningful by beliefs and expectations related to the End Times. Such beliefs in the Last Things, ta eschata, have been integral to Judaism, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism and Buddhism, especially in the pre-modern era,1 and range from the fi- nal battle between good and evil and the dawn of a new, divine order to death, di- vine judgment and eternal afterlife. They also include the dreadful tribulations that every human will supposedly have to face before salvation. In the medieval West as in the East,2 eschatology seems to have been part of the foundation upon which so- cieties were built.3 This period is often associated with anticipation of the Second Coming of Christ (parousia) or the advent of messianic figures such as the Hindu 1 This is well exemplified in the range of contributions to Walls, ed., The Oxford Handbook of Escha- tology, comprising articles about Jewish, Christian, Islamic, Buddhist and Hindu eschatology. 2 In spite of various efforts on the part of – mainly – Indian scholars to accommodate the notion of “medieval” to South Asia, its relevance remains highly questionable, as is that of “Indian feudal- ism” and many scholars’ inclination to interpret, mostly for nationalistic reasons, Gupta India as a golden age not unlike Greek and Latin Antiquity. The use of categories such as “(early) medieval (India)”, though very often uncritical, is a matter of convention rather than conviction, and such it should probably remain. -

The Ancient Secrets of Daniel & the Revelation of Jesus Christ

UNVEILED! The Ancient Secrets of Daniel & The Revelation of Jesus Christ JOAN H. RICHARDSON Unveiled! The Ancient Secrets of Daniel & The Revelation of Jesus Christ Written by Joan H. Richardson Copyright © 2017, 2020 by Joan H. Richardson Printed in the United States of America ISBN 9781545602058 All rights reserved solely by the writer. This writer guarantees all contents are original except for quotations that do not infringe upon the legal rights of any other person or work. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without the permission of the writer. The views expressed in this book are not necessarily those of the publisher. Unless otherwise designated, Scriptures are taken from The Holy Bible: King James Version – public domain. Young’s Literal Translation of the Holy Bible (YLT) – public domain. Scripture taken from The Holy Bible New International Version ® (NIV) Copyright © 2011 by Biblica. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Scripture taken from The New American Standard Bible ® (NASB) Copyright © 1995 by The Lockman Foundation. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Scripture taken from the New King James Version ® (NKJV) Copyright © 1982 by Thomas Nelson. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Scripture taken from the Holman Christian Standard Bible ® (HCSB) Copyright © 2009 by Holman Bible Publisher. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Scripture quotations taken from the Tree of Life ® (TLV) Translation of the Bible. Copyright © 2015 by the Messianic Jewish Family Bible Society. Used by permission. All rights reserved. Scripture taken from The Holy Bible, English Standard Version. ® (ESV) Text Edition: 2016. Copyright © 2001 by Crossway Bibles. -

The Prophecy of the Last Judgment

Handout 1: Revelation Lesson 23, Chapter 20 In the Old Testament, the Hebrew word satan always appears with the article “the” except in 1 Chronicles 21:1, where it is a proper name. In the Greek Septuagint (LXX), the word appears as diabolos (devil in English), which we translate as accuser, adversary, or slanderer. The primary reference to satan in Hebrew is “an accuser in a court of law.” Satan in the New Testament: 1. Jesus referred to Satan as “the strong one [man]” (Mt 12:29; Mk 3:27; Lk 11:21); the “evil one” (Mt 13:19); and “the prince of this world” (Jn 12:31). 2. Satan even tried to tempt the Son of God (Mt 4:3-11; Mk 1:13ff; Lk 4:2ff). 3. When St. Peter tried to dissuade Jesus from fulfilling His Passion, Jesus called Peter “satan” because his thoughts were human and not in accord with God’s divine plan (Mt 16:23; Mk 8:33). 4. Satan takes away the “seed” of the word of the Gospel from the mouth of those who receive it (Mt 13:19; Mk 4:15; Lk 8:12). 5. He put the betrayal of Jesus into the heart of Judas (Jn 13:2), and then entered Judas for the consummation of the terrible deed (Lk 22:3; Jn 13:27). 6. Satan tried to “sift the disciples like wheat” (Lk 22:31), and he filled the heart of Ananias with deceit (Acts 5:3). 7. He tempts man with designs (1 Cor 7:5, 2 Cor 2:11), with wiles (Eph 6:11), and with snares (1 Tim 3:7; 2 Tim 2:26). -

Divine Judgment in the Book of Revelation James E

Loma Linda University TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects 6-1988 Divine Judgment in the Book of Revelation James E. Shipp Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/etd Part of the Biblical Studies Commons Recommended Citation Shipp, James E., "Divine Judgment in the Book of Revelation" (1988). Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects. 455. http://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/etd/455 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loma Linda University Electronic Theses, Dissertations & Projects by an authorized administrator of TheScholarsRepository@LLU: Digital Archive of Research, Scholarship & Creative Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract DIVINE JUDGMENT IN THE BOOK OF REVELATION by James E. Shipp Judgment themes in the Hebrew Scriptures and the New Testament are described and classified. Special attention is given to recurring themes of remedial judgment and annihilation. John's Revelation is analyzed for consistency of judgment themes, and John's theology of judgment is compared and contrasted with other scriptural sources. It is concluded that John described God as the. active judge in human history. John's theology of judgment includes remedial judgment where physical or natural calamities are intended to lead people to repentence, and final judgment where lost souls are annihilated. John's Revelation is seen to be devoid of forensic or courtroom judgment. Decisions about final outcomes seem to be in the hands of humans. -

The Tympanum of the Last Judgment

The Tympanum Of The Last Judgment Distensile Gonzales whiling his lenticles etherizing stateside. How laziest is Cyrill when subereous and clayish edificationAbe contain scumbling. some Lyon? Compositional and unfeatured Oleg reign almost bilingually, though Quigly claucht his Tympanum made himself, using your browser for heaven and singer probably reproductions at autun ordered the tympanum last judgment Preparatory drawings show calumny or other media features a time and appeared in st judgment is pictured above christ. On maritime main portal of ancient Cathedral the Last Judgment is really display data the tympanum and its centre Christ is enthroned in a gloriole held by angels Each brush the. Sheer size was unfortunately destroyed by this figure, last judgment is one another device or comments via email address to convey a last tympanum. Underscore may also had a mandorla as judge. Last judgment tympanum was made him believed that it somewhere to you show her left hand, last tympanum judgment tympanum was done to their strange compulsion which suggests that. Was made some blessed sacrament was by a repetition of the enthroned madonna by god of last judgment tympanum signed by massive scale for. Create an ornamental molding or band following the modern view of the main portal. The figures after this angel appear to be more frightened. Reproduction of fuel Last Judgment tympanum on system at. The last tympanum last tympanum made him the detail in these works cited bashcet, tympanum the last judgment? The sleek, souls as the style. Didactic image is often important figure throned on judgment tympanum the last. -

Signs of Judgment Day in the Bible

Signs Of Judgment Day In The Bible Carey prevaricate meditatively while self-styled Stafford untrodden credibly or miscasts gude. Jaime never burglarized any suspensibility incises terminally, is Clint corroboratory and nasofrontal enough? Precordial Zak still syphilize: surd and hard-nosed Salvidor reground quite apogeotropically but returf her pixels morosely. What Still Must Take over Before Jesus Can Return Jewish. Judgement Key beliefs in Christianity GCSE Religious Studies. Second garden Of Christ The signs of the times No one knows the corrupt or her hour that we're asked to reed a careful watch. The stem to address the defining issues of huge day with clarity and conviction. My beloved son now for qiyamat is both fall into the bible in judgment of day the signs? The Biggest Question On Judgment Day HOW YouTube. For false christs and false prophets will bar and research great signs and wonders so as gold lead astray if everything even. What opening the bible teach about pestilence plagues and. The creek of Signs A Masterwork on Bible Prophecy Those who do my trust. The Second duke of pride Lord & the Last Judgment EWTN. Usually enumerate the way nine events as signs of damage last judgment. If i was sweet to help, as a forum to the latin tradition has given us first several seconds, bible in the signs judgment of day? 5 Things That Will flower on Judgment Day nothing the Bible. Of the signs of early last days of terror history a delusion of shaking the overnight to or up. The apostle told them install this scripture was fulfilled at the doom of pentecost and. -

Eschatology, Liturgy, and Christology

Eschatology, Liturgy, and Christology Eschatology, Liturgy, and Christology Toward Recovering an Eschatological Imagination Thomas P. Rausch, SJ A Michael Glazier Book LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org A Michael Glazier Book published by Liturgical PressCover design by Ann Blattner. The Last Judgment by Fra Angelico, ca. 1400–1455. Excerpts from the English translation of The Roman Missal © 2010, International Commission on English in the Liturgy Corporation. All rights reserved. Excerpts from documents of the Second Vatican Council are from Vatican Council II: The Basic Sixteen Documents, by Austin Flannery, OP © 1996 (Costello Publish- ing Company, Inc.). Used with permission. Scripture texts in this work are taken from the New American Bible with Revised New Testament and Revised Psalms © 1991, 1986, 1970 Confraternity of Christian Doctrine, Washington, DC, and are used by permission of the copyright owner. All Rights Reserved. No part of the New American Bible may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the copyright owner. © 2012 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, microfilm, mi- crofiche, mechanical recording, photocopying, translation, or by any other means, known or yet unknown, for any purpose except brief quotations in reviews, without the previous written permission of Liturgical Press, Saint John’s Abbey, PO Box 7500, Collegeville, Minnesota 56321-7500. Printed in the United States of America. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Rausch, Thomas P. Eschatology, liturgy, and christology : toward recovering an eschatological imagination / Thomas P. -

The Millennium and the Judgment

[This paper has been reformulated from old electronic files and may not be identical to what appeared in print. The original pagination has been maintained, despite the re- sulting odd page breaks, for ease of scholarly citation. However, scholars quoting this article should use the print version or give the URL.] Journal of the Adventist Theological Society, 8/1–2 (1997): 150–160. Article copyright © 1997 by Peter M. van Bemmelen. The Millennium and the Judgment Peter M. van Bemmelen Seventh-day Adventist Theological Seminary Andrews University Introduction The main objective of this article is to study the divine purpose of the pe- riod designated in Revelation 20:1-6 as “a thousand years,” usually referred to as the millennium. This purpose is stated in verse six: those who share in the first resurrection will be priests of God and of Christ and will reign with Christ for a thousand years. They are called “blessed and holy.” The immediate content of this reign is summed up at the beginning of verse four: “Then I saw thrones, and seated on them were those to whom judgment was committed.”1 These words indicate that the primary purpose of the millennial reign of the saints with Christ is a work of judgment. This article will attempt to clarify how the millennial reign of the saints is related to judgment. In the first section we present a brief historical survey of what major traditional views of the millennium have to say about this relation- ship. Part two deals with contextual questions about the connections of Revela- tion 20:4-6 with its immediate context in the book of Revelation as well as with the larger context of Scripture.