Approaches to Medieval Cultures of Eschatology

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE APOCALYPTIC WAR AGAINST GOG of MAGOG. MARTIN BUBER VERSUS MEIR KAHANE Por: Rico Sneller

EL CONFLICTO PALESTINO-ISRAELI: SOLUCIONES Y DERIVAS Profesor David Noel Ramírez Padilla Rector del Tecnológico de Monterrey Lic. Héctor Núñez de Cáceres Rector de la Zona Occidente Ing. Salvador Coutiño Audiffred Dr. Ricardo Romero Gerbaud Director General del Campus Querétaro Dirección Dr. Ricardo Romero Gerbaud Mtro. José Manuel Velázquez Hurtado Director de Profesional y Graduados en María José Juárez Becerra Administración y Ciencias Sociales Edición Mtra. Angélica Camacho Aranda Natalia Fernández, Alicia Hernández, Rodrigo Directora del Departamento de Relaciones Pesce Internacionales y Formación Humanística Asistentes de Edición Mtro. Kacper Przyborowski Director de la Licenciatura en Relaciones Internacionales Dr. Tomás Pérez Vejo Dra. Marisol Reyes Soto Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia INAH University of Queens, Ireland Dra. Avital Bloch Dr. Tamir Bar-On Universidad de Colima Tecnológico de Monterrey Dra. Marie-Joelle Zahar Université de Montréal Dra. Claudia Barona Castañeda Universidad de Las Américas Puebla Dr. Thomas Wolfe University of Minnesota, Twin-Cities Dr. Janusz Mucha AGH, Cracovia GRUPO FORUM Retos Internacionales, ISSN: 2007-8390. Año 5, No. 11, Agosto-Diciembre 2014, publicación semestral. Editada por el Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey, Campus Querétaro, a través de la División de Administración y Ciencias Sociales, bajo la dirección del Departamento deRelaciones Internacionales y Humanidades, domicilio Av. Eugenio Garza Sada No. 2501, Col. Tecnológico, C.P. 64849, Monterrey, N.L. Editor responsable: Dr. Ricardo Romero Gerbaud. Datos de contacto: [email protected], http://retosinternacionales.com, teléfono y fax: 52 (442) 238 32 34. Impresa por FORUM arte y comunicación S.A. de C.V., domicilio Av. del 57, número 12, Colonia Centro, C.P. -

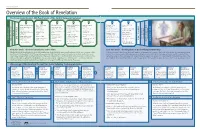

Overview of the Book of Revelation the Seven Seals (Seven 1,000-Year Periods of the Earth’S Temporal Existence)

NEW TESTAMENT Overview of the Book of Revelation The Seven Seals (Seven 1,000-Year Periods of the Earth’s Temporal Existence) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Adam’s ministry began City of Enoch was Abraham’s ministry Israel was divided into John the Baptist’s Renaissance and Destruction of the translated two kingdoms ministry Reformation wicked Wickedness began to Isaac, Jacob, and spread Noah’s ministry twelve tribes of Israel Isaiah’s ministry Christ’s ministry Industrial Revolution Christ comes to reign as King of kings Repentance was Great Flood— Israel’s bondage in Ten tribes were taken Church was Joseph Smith’s ministry taught by prophets and mankind began Egypt captive established Earth receives Restored Church patriarchs again paradisiacal glory Moses’s ministry Judah was taken The Savior’s atoning becomes global CREATION Adam gathered and Tower of Babel captive, and temple sacrifice Satan is bound Conquest of land of Saints prepare for Christ EARTH’S DAY OF DAY EARTH’S blessed his children was destroyed OF DAY EARTH’S PROBATION ENDS PROBATION PROBATION ENDS PROBATION ETERNAL REWARD FALL OF ADAM FALL Jaredites traveled to Canaan Gospel was taken to Millennial era of peace ETERNAL REWARD ETERNITIES PAST Great calamities Great calamities FINAL JUDGMENT FINAL JUDGMENT PREMORTAL EXISTENCE PREMORTAL Adam died promised land Jews returned to the Gentiles and love and love ETERNITIES FUTURE Israelites began to ETERNITIES FUTURE ALL PEOPLE RECEIVE THEIR Jerusalem Zion established ALL PEOPLE RECEIVE THEIR Enoch’s ministry have kings Great Apostasy and Earth -

End Time Chronology from Jesus in the Olivet Discourse (Matthew 24, Mark 13, Luke 21) Shawn Nelson

November 5, 2017 End Time Chronology from Jesus in the Olivet Discourse (Matthew 24, Mark 13, Luke 21) Shawn Nelson (1) How does Matthew 24 fit into our on-going study? The view we’ve been teaching (Premillennialism) says there will be a literal world leader (antichrist) who is able to establish peace treaty in the Middle East between Israel and her neighbors for 7 years (Dan. 9:24-27). In the middle of the 7 years he walks into the temple in Jerusalem, takes away the sacrifices (Dan. 12:11), and declares himself to be God (Dan. 9:27; 11:31; Matt. 24:15; Mark 13:14; 2 Thess. 2:3-4). He forces everybody to worship him (2 Thess. 2:4; Rev. 13:15) and requires them to have a mark in order to buy or sell anything anywhere in the world (Rev. 13:16). Matthew 24 helps us see that Jesus’ taught the above scenario too. Jesus mentions all of the following: the existence of the nation of Israel, the temple in Jerusalem, the antichrist, tribulation, the second coming (and possibly rapture). The Temple to Be Destroyed 24 Then Jesus went out and departed from the temple, and His disciples came up to show Him the buildings of the temple. 2 And Jesus said to them, “Do you not see all these things? [the Jerusalem temple] Assuredly, I say to you, not one stone shall be left here upon another, that shall not be thrown down.” The Disciples’ Two Questions 3 Now as He sat on the Mount of Olives, the disciples came to Him privately, saying, “Tell us, when will these things be? [temple being destroyed] And what will be the sign of Your coming, and of the end of the age?” The Tribulation 4 And Jesus answered and said to them: “Take heed that no one deceives you. -

Babylonian Populations, Servility, and Cuneiform Records

Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient 60 (2017) 715-787 brill.com/jesh Babylonian Populations, Servility, and Cuneiform Records Jonathan S. Tenney Cornell University [email protected] Abstract To date, servility and servile systems in Babylonia have been explored with the tradi- tional lexical approach of Assyriology. If one examines servility as an aggregate phe- nomenon, these subjects can be investigated on a much larger scale with quantitative approaches. Using servile populations as a point of departure, this paper applies both quantitative and qualitative methods to explore Babylonian population dynamics in general; especially morbidity, mortality, and ages at which Babylonians experienced important life events. As such, it can be added to the handful of publications that have sought basic demographic data in the cuneiform record, and therefore has value to those scholars who are also interested in migration and settlement. It suggests that the origins of servile systems in Babylonia can be explained with the Nieboer-Domar hy- pothesis, which proposes that large-scale systems of bondage will arise in regions with * This was written in honor, thanks, and recognition of McGuire Gibson’s efforts to impart a sense of the influence of aggregate population behavior on Mesopotamian development, notably in his 1973 article “Population Shift and the Rise of Mesopotamian Civilization”. As an Assyriology student who was searching texts for answers to similar questions, I have occasionally found myself in uncharted waters. Mac’s encouragement helped me get past my discomfort, find the data, and put words on the page. The necessity of assembling Mesopotamian “demographic” measures was something made clear to me by the M.A.S.S. -

A Re-Examination of the Millennium in Rev 20:1–6: Consummation and Recapitulation

JETS 44/2 (June 2001) 237–51 A RE-EXAMINATION OF THE MILLENNIUM IN REV 20:1–6: CONSUMMATION AND RECAPITULATION dave mathewson* i. introduction The question of the so-called millennial kingdom in Rev 20:1–6 continues to be a source of fascination in evangelical discussion and dialogue.1 The purpose of this article is to re-examine the question of the millennial king- dom as articulated in Rev 20:1–6. More specifically, this article will consider the meaning and function of 20:1–6 within Revelation as it relates to the contemporary debate about whether this section is best understood within a premillennial or amillennial framework. Hermeneutically, most of the de- bate has centered around how literally the reference to the one thousand years in 20:1–6 should be taken and, more importantly, the relationship be- tween 20:1–6 and 19:11–21. Does the thousand year period in 20:1–6 re- fer to a more or less literal period of time?2 Or should it be understood more symbolically? Does 20:1–6 follow 19:11–21 chronologically, with the one thou- sand years featuring a Zwischenreich (premillennialism), or does the final battle in 20:7–10 recapitulate the battle in 19:11–21, with the reference to the one thousand years in 20:1–6 extending all the way back to the first coming of Christ (amillennialism)?3 * Dave Mathewson is instructor in New Testament at Oak Hills Christian College, 1600 Oak Hills Road SW, Bemidji, MN 56601. 1 Cf. R. -

Apocalyptic Millennialism in the West: the Case of the Solar Temple

Apocalyptic Millennialism in the West: The Case of the Solar Temple Jean Francois Mayer Ministry of Defense of Switzerland University of Fribourg author of The Solar Temple and other works on emergent religious movements Discussion and Commentary by: • Jeffrey K. Hadden, Professor of Sociology, UVA • David G. Bromley, Professor of Sociology and Religious Studies, Virginia Commonwealth University • James T. Richardson, Professor of Sociology and Judicial Studies, University of Nevada • Gregory Saathoff, M.D. Associate Professor of Clinical Psychiatric Medicine, and Executive Director of the Critical Incident Analysis Group, UVA A presentation held on Friday, November 13, 1998 at The University of Virginia Sponsored by: The Critical Incident Analysis Group at the University of Virginia Department of Sociology, Department of Religious Studies UVA Continuing Education Center for Study of Mind and Human Interaction Apocalyptic Millennialism in the West:The Case of the Solar Temple Copyright © 1998 by the Rector and Board of Visitors of the University of Virginia Critical Incident Analysis Group 1 INTRODUCTION Gregory B. Saathoff, M.D. Executive Director, Critical Incident Analysis Group On November 13, 1998, the University of Virginia was pleased to host an important session that examined many issues surrounding the emergence of Apocalyptic Millenialism in the 1990s. This event was organized by the Critical Incident Analysis Group at the University of Virginia, and co-sponsored by the Departments of Religious Studies and Sociology, and by the Medical School’s Center for the Study of Mind and Human Interaction. As the year 2000 approaches, many groups with apocalyptic, violent, and even suicidal designs are becoming prominent in their preparations for catastrophic, millennial events. -

Reading the Book of Revelation Politically

start page: 339 Stellenbosch eological Journal 2017, Vol 3, No 2, 339–360 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17570/stj.2017.v3n2.a15 Online ISSN 2413-9467 | Print ISSN 2413-9459 2017 © Pieter de Waal Neethling Trust Reading the Book of Revelation politically De Villiers, Pieter GR University of the Free State [email protected] Abstract In this essay the political use of Revelation in the first five centuries will be analysed in greatest detail, with some references to other examples. Focus will be on two trajectories of interpretation: literalist, eschatological readings and symbolic, spiritualizing interpretations of the text. Whilst the first approach reads the book as predictions of future events, the second approach links the text with spiritual themes and contents that do not refer to outstanding events in time and history. The essay will argue that both of these trajectories are ultimately determined by political considerations. In a final section, a contemporary reading of Revelation will be analysed in order to illustrate the continuing and important presence of political readings in the reception history of Revelation, albeit in new, unique forms. Key words Book of Revelation; eschatological; symbolic; spiritualizing; political considerations 1. Introduction Revelation is often associated with movements on the fringes of societies that are preoccupied with visions and calculations about the end time.1 The book has also been used throughout the centuries to reflect on and challenge political structures and 1 Cf. Barbara R. Rossing, The Rapture Exposed: the Message of Hope in the Book of Revelation (Westview Press, Boulder, CO., 2004). Robert Jewett, Jesus against the Rapture. -

Gog and Magog and Ethnic Difference in the Catalan Atlas (1375) Thomas Franke

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository History ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 9-12-2014 Monsters at the End of Time: Gog and Magog and Ethnic Difference in the Catalan Atlas (1375) Thomas Franke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds Recommended Citation Franke, Thomas. "Monsters at the End of Time: Gog and Magog and Ethnic Difference in the Catalan Atlas (1375)." (2014). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds/30 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in History ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thomas Samuel Franke Candidate History Department This thesis is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Thesis Committee: Michael A. Ryan , Chairperson Timothy C. Graham Sarah Davis-Secord Franke i MONSTERS AT THE END OF TIME: GOG AND MAGOG AND ETHNIC DIFFERENCE IN THE CATALAN ATLAS (1375) by THOMAS FRANKE BACHELOR OF ARTS, UC IRVINE 2012 THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS HISTORY The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico JULY 2014 Franke ii Abstract Franke, Thomas. Monsters at the End of Time: Gog and Magog and Ethnic Difference in the Catalan Atlas (1375). University of New Mexico, 2014. Although they are only mentioned briefly in Revelation, the destructive Gog and Magog formed an important component of apocalyptic thought for medieval European Christians, who associated Gog and Magog with a number of non-Christian peoples. -

Imagining Ritual and Cultic Practice in Koguryŏ Buddhism

International Journal of Korean History (Vol.19 No.2, Aug. 2014) 169 Imagining Ritual and Cultic Practice in Koguryŏ Buddhism Richard D. McBride II* Introduction The Koguryŏ émigré and Buddhist monk Hyeryang was named Bud- dhist overseer by Silla king Chinhŭng (r. 540–576). Hyeryang instituted Buddhist ritual observances at the Silla court that would be, in continually evolving forms, performed at court in Silla and Koryŏ for eight hundred years. Sparse but tantalizing evidence remains of Koguryŏ’s Buddhist culture: tomb murals with Buddhist themes, brief notices recorded in the History of the Three Kingdoms (Samguk sagi 三國史記), a few inscrip- tions on Buddhist images believed by scholars to be of Koguryŏ prove- nance, and anecdotes in Memorabilia of the Three Kingdoms (Samguk yusa 三國遺事) and other early Chinese and Japanese literary sources.1 Based on these limited proofs, some Korean scholars have imagined an advanced philosophical tradition that must have profoundly influenced * Associate Professor, Department of History, Brigham Young University-Hawai‘i 1 For a recent analysis of the sparse material in the Samguk sagi, see Kim Poksun 金福順, “4–5 segi Samguk sagi ŭi sŭngnyŏ mit sach’al” (Monks and monasteries of the fourth and fifth centuries in the Samguk sagi). Silla munhwa 新羅文化 38 (2011): 85–113; and Kim Poksun, “6 segi Samguk sagi Pulgyo kwallyŏn kisa chonŭi” 存疑 (Doubts on accounts related to Buddhism in the sixth century in the Samguk sagi), Silla munhwa 新羅文化 39 (2012): 63–87. 170 Imagining Ritual and Cultic Practice in Koguryŏ Buddhism the Sinitic Buddhist tradition as well as the emerging Buddhist culture of Silla.2 Western scholars, on the other hand, have lamented the dearth of literary, epigraphical, and archeological evidence of Buddhism in Kogu- ryŏ.3 Is it possible to reconstruct illustrations of the nature and characteris- tics of Buddhist ritual and devotional practice in the late Koguryŏ period? In this paper I will flesh out the characteristics of Buddhist ritual and devotional practice in Koguryŏ by reconstructing its Northeast Asian con- text. -

The Late Northern Dynasties Buddhist Statues at Qingzhou and the Qingzhou Style

The Late Northern Dynasties Buddhist Statues at Qingzhou and the Qingzhou Style Liu Fengjun Keywords: late Northern Dynasties Qingzhou area Buddhist statues Qingzhou style In recent years fragmentary Buddhist statues have been Northern Qi period. (3) In the winter of 1979, 40 small frequently unearthed in large numbers in Qingzhou 青州 and large fragmentary statues and some lotus socles were and the surrounding area, including Boxing 博兴, discovered at the Xingguo Temple 兴国寺 site in Gaoqing 高青, Wudi 无棣, Linqu 临朐, Zhucheng 诸 Qingzhou, mainly produced between the end of North- 城, and Qingdao 青岛. Especially notable are the large ern Wei and Northern Qi period. There were also two quantities of statues at the site of the Longxing Temple Buddha head sculptures of the Sui and Tang periods. (4) 龙兴寺 at Qingzhou. The discovery of these statues drew In the 1970s, seven stone statues were discovered at great attention from academic circles. The significance He’an 何庵 Village, Wudi County. Four of them bear of these statues is manifold. I merely intend to under take Northern Qi dates. (5) In November 1987, one single a tentative study of the causes and date of the destruction round Bodhisattva stone sculpture of the Eastern Wei of the Buddhist statues and of the artistic features of the period and one round Buddhist stone sculpture of the Qingzhou style statues. Northern Qi period were discovered on the South Road of Qingzhou. Both works were painted colorfully and I. Fragmentary Buddhist Statues of the Late partly gilt. They were preserved intact and remained Northern Dynasties Unearthed in the Qingzhou Area colorful. -

A HARMONY of JUDEO-CHRISTIAN ESCHATOLOGY and MESSIANIC PROPHECY James W

African Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Research ISSN: 2689-5129 Volume 4, Issue 3, 2021 (pp. 65-80) www.abjournals.org A HARMONY OF JUDEO-CHRISTIAN ESCHATOLOGY AND MESSIANIC PROPHECY James W. Ellis Cite this article: ABSTRACT: This essay presents a selective overview of the James W. Ellis (2021), A main themes of Judeo-Christian eschatological prophecy. Harmony of Judeo-Christian Particular attention is paid to the significance of successive Eschatology and Messianic biblical covenants, prophecies of the “day of the Lord,” Prophecy. African Journal of Social Sciences and differences between personal and collective resurrection, and Humanities Research 4(3), 65- expectations of the Messianic era. Although the prophets of the 80. DOI: 10.52589/AJSSHR- Hebrew Bible and Christian New Testament lived and wrote in 6SLAJJHX. diverse historical and social contexts, their foresights were remarkably consistent and collectively offered a coherent picture Manuscript History of the earth’s last days, the culmination of human history, and the Received: 24 May 2021 prospects of the afterlife. This coherence reflects the interrelated Accepted: 22 June 2021 character of Judaic and Christian theology and the unity of the Judeo-Christian faith. Published: 30 June 2021 KEYWORDS: Eschatology, Judeo-Christian, Messiah, Copyright © 2020 The Author(s). Prophecy. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0), which permits anyone to share, use, reproduce and redistribute in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. 65 Article DOI: 10.52589/AJSSHR-6SLAJJHX DOI URL: https://doi.org/10.52589/AJSSHR-6SLAJJHX African Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Research ISSN: 2689-5129 Volume 4, Issue 3, 2021 (pp. -

Millennialism, Rapture and “Left Behind” Literature. Analysing a Major Cultural Phenomenon in Recent Times

start page: 163 Stellenbosch Theological Journal 2019, Vol 5, No 1, 163–190 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17570/stj.2019.v5n1.a09 Online ISSN 2413-9467 | Print ISSN 2413-9459 2019 © Pieter de Waal Neethling Trust Millennialism, rapture and “Left Behind” literature. Analysing a major cultural phenomenon in recent times De Villers, Pieter GR University of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa [email protected] Abstract This article represents a research overview of the nature, historical roots, social contexts and growth of millennialism as a remarkable religious and cultural phenomenon in modern times. It firstly investigates the notions of eschatology, millennialism and rapture that characterize millennialism. It then analyses how and why millennialism that seems to have been a marginal phenomenon, became prominent in the United States through the evangelistic activities of Darby, initially an unknown pastor of a minuscule faith community from England and later a household name in the global religious discourse. It analyses how millennialism grew to play a key role in the religious, social and political discourse of the twentieth century. It finally analyses how Darby’s ideas are illuminated when they are placed within the context of modern England in the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth century. In a conclusion some key challenges of the place and role of millennialism as a movement that reasserts itself continuously, are spelled out in the light of this history. Keywords Eschatology; millennialism; chiliasm; rapture; dispensationalism; J.N. Darby; Joseph Mede; Johann Heinrich Alsted; “Left Behind” literature. 1. Eschatology and millennialism Christianity is essentially an eschatological movement that proclaims the fulfilment of the divine promises in Hebrew Scriptures in the earthly ministry of Christ, but it also harbours the expectation of an ultimate fulfilment of Christ’s second coming with the new world of God that will replace the existing evil dispensation.