A Re-Examination of the Millennium in Rev 20:1–6: Consummation and Recapitulation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

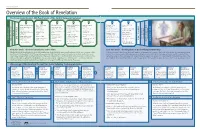

Overview of the Book of Revelation the Seven Seals (Seven 1,000-Year Periods of the Earth’S Temporal Existence)

NEW TESTAMENT Overview of the Book of Revelation The Seven Seals (Seven 1,000-Year Periods of the Earth’s Temporal Existence) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Adam’s ministry began City of Enoch was Abraham’s ministry Israel was divided into John the Baptist’s Renaissance and Destruction of the translated two kingdoms ministry Reformation wicked Wickedness began to Isaac, Jacob, and spread Noah’s ministry twelve tribes of Israel Isaiah’s ministry Christ’s ministry Industrial Revolution Christ comes to reign as King of kings Repentance was Great Flood— Israel’s bondage in Ten tribes were taken Church was Joseph Smith’s ministry taught by prophets and mankind began Egypt captive established Earth receives Restored Church patriarchs again paradisiacal glory Moses’s ministry Judah was taken The Savior’s atoning becomes global CREATION Adam gathered and Tower of Babel captive, and temple sacrifice Satan is bound Conquest of land of Saints prepare for Christ EARTH’S DAY OF DAY EARTH’S blessed his children was destroyed OF DAY EARTH’S PROBATION ENDS PROBATION PROBATION ENDS PROBATION ETERNAL REWARD FALL OF ADAM FALL Jaredites traveled to Canaan Gospel was taken to Millennial era of peace ETERNAL REWARD ETERNITIES PAST Great calamities Great calamities FINAL JUDGMENT FINAL JUDGMENT PREMORTAL EXISTENCE PREMORTAL Adam died promised land Jews returned to the Gentiles and love and love ETERNITIES FUTURE Israelites began to ETERNITIES FUTURE ALL PEOPLE RECEIVE THEIR Jerusalem Zion established ALL PEOPLE RECEIVE THEIR Enoch’s ministry have kings Great Apostasy and Earth -

How John Nelson Darby Went Visiting: Dispensational Premillennialism In

University of Dayton eCommons History Faculty Publications Department of History 2000 How John Nelson Darby Went Visiting: Dispensational Premillennialism in the Believers Church Tradition and the Historiography of Fundamentalism William Vance Trollinger University of Dayton, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://ecommons.udayton.edu/hst_fac_pub Part of the Comparative Methodologies and Theories Commons, History of Christianity Commons, History of Religion Commons, Other History Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons eCommons Citation Trollinger, William Vance, "How John Nelson Darby Went Visiting: Dispensational Premillennialism in the Believers Church Tradition and the Historiography of Fundamentalism" (2000). History Faculty Publications. Paper 8. http://ecommons.udayton.edu/hst_fac_pub/8 This Book Chapter is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Contents Introduction ............................................... ............ .. .... ....... .... .............. .. .. .. .. ......... 7 PART ONE: BIBLICAL PERSPECTIVES 1 Making Prophecy Come True: Human Responsibility for the End of the World, JAMES E. BRENNEMAN .... .............................................................. 21 2 Lions and Ovens and Visions, 0 My! A Satirical -

The City: the New Jerusalem

Chapter 1 The City: The New Jerusalem “I saw the holy city, the New Jerusalem” (Revelation 21:2). These words from the final book of the Bible set out a vision of heaven that has captivated the Christian imagina- tion. To speak of heaven is to affirm that the human long- ing to see God will one day be fulfilled – that we shall finally be able to gaze upon the face of what Christianity affirms to be the most wondrous sight anyone can hope to behold. One of Israel’s greatest Psalms asks to be granted the privilege of being able to gaze upon “the beauty of the Lord” in the land of the living (Psalm 27:4) – to be able to catch a glimpse of the face of God in the midst of the ambiguities and sorrows of this life. We see God but dimly in this life; yet, as Paul argued in his first letter to the Corinthian Christians, we shall one day see God “face to face” (1 Corinthians 13:12). To see God; to see heaven. From a Christian perspective, the horizons defined by the parameters of our human ex- istence merely limit what we can see; they do not define what there is to be seen. Imprisoned by its history and mortality, humanity has had to content itself with pressing its boundaries to their absolute limits, longing to know what lies beyond them. Can we break through the limits of time and space, and glimpse another realm – another dimension, hidden from us at present, yet which one day we shall encounter, and even enter? Images and the Christian Faith It has often been observed that humanity has the capacity to think. -

Premillennialism in the New Testament: Five Biblically Doctrinal Truths

MSJ 29/2 (Fall 2018) 177–205 PREMILLENNIALISM IN THE NEW TESTAMENT: FIVE BIBLICALLY DOCTRINAL TRUTHS Gregory H. Harris Professor of Bible Exposition The Master’s Seminary Many scholars hold that premillennial statements are found only in Revelation 20:1–10. Although these verses are extremely important in supporting the premillen- nial doctrine, many other verses throughout the New Testament also offer support for premillennialism. Our study limits itself to five biblically doctrinal premillennial truths from the New Testament that seamlessly blend throughout the Bible with the person and work—and reign—of Jesus the Messiah on earth after His Second Com- ing. * * * * * Introduction Whenever discussions between premillennialists and amillennialists occur, Revelation 19 and 20 is usually the section of Scripture on which many base their argumentation, especially Revelation 20:1–10. Before we examine these specific pas- sages, we know that God has already made several prophecies elsewhere. And how one interprets these passages has been determined long before by how those other related futuristic biblical texts have already been interpreted, before ever approaching certain crucial biblical passages such as Revelation 20:1–10. So, as we shall see, one should actually end the argumentation for this important component of eschatological theology in Revelation 19–20, not start there. In setting forth the New Testament case for premillennialism we will present the following: (1) a presentation of three of the five premillennial biblical truths -

The Chronology of Revelation 19—20

Session #5 The Chronology of Revelation 19—20 The Expositors Seminary Super Seminar—April 8–9, 2016 I. Introduction § Key Question: Do the events of Rev 20:1–6 follow the events of Rev 19:11–21? OR Does Rev 20 take the reader back to the beginning of the NT era so that verses 1–6 describe the present age? Comparison of Views Ø The Sequential View of Premillennialism The Millennium of Rev 20 ____________ the Second Coming of Rev 19 Ø The Recapitulation View of Amillennialism The Millennium of Rev 20 ____________ the Second Coming of Rev 19 II. The Sequential View of Premillennialism A. The Introductory “And I Saw” (Rev 20:1) § Used _______ in Book of Revelation § Almost always introduces _______________ ________________ § Argument is _______________ but places burden of proof on amillennial view B. The Content of the Visions (Rev 20:1–6) § The binding of Satan is ____________ (not present) § The first resurrection is ____________ (not spiritual) § The thousand years is ____________ (not symbolic) Ø Therefore: The chronology of Rev 19-20 must be ________________! 19 C. The Use of “Any Longer” (Rev 20:3) § Rev 12–19 repeatedly highlights the satanic deception of the nations in the second half of the Tribulation (12:9; 13:14; 16:14; 18:23; 19:19–20). § Satan is then locked in the abyss “so that he would not deceive the nations any longer” (Rev 20:3), which indicates the interruption of a deception that was already taking place. § This connection indicates a historical progression in which the binding of Rev 20 is designed to halt the deception described in Rev 12–19. -

Visions of the End? Revelation and Climate Change

Visions of the End? Revelation and Climate Change By The Revd Professor T.J. Gorringe; a chapter from Sebastian Kim and Jonathan Draper (eds.) Christianity and the Renewal of Nature, SPCK, 2011; reproduced with kind permission of the author and publisher. Rev 8: 1 When the Lamb opened the seventh seal, there was silence in heaven for about half an hour. In chapter four of Revelation the author tells us that the song of praise before God ‘never ceases’ (4:8), but now there is silence. ‘Heaven seems to hold its breath because of what is about to happen on earth’. Perhaps the author is thinking of the passage in 2 Esdras where the world returns to its “original silence” as “at the beginning of creation” when nobody will be left alive (7:30 cf.6:39)i. It is an intensely dramatic image which has caught people’s imaginations all the way from the first century to Ingmar Bergman. It could speak about the fear we feel about the possible effects of climate change as represented by James Lovelock in The Revenge of Gaia, or Mark Lynas in Six Degrees. But the silence does not last. Seven trumpets are given to seven angels. These may be the seven archangels found in Jewish tradition and in this tradition trumpets are used to warn or to call. “All you inhabitants of the world, when a trumpet is blown, hear!” says Isaiah(Is.18:3) It is the task of prophets as watchmen to call the people to “give heed to the sound of the trumpet”, to hear the warning says Jeremiah (Jer 6:17 ). -

Apocalyptic Millennialism in the West: the Case of the Solar Temple

Apocalyptic Millennialism in the West: The Case of the Solar Temple Jean Francois Mayer Ministry of Defense of Switzerland University of Fribourg author of The Solar Temple and other works on emergent religious movements Discussion and Commentary by: • Jeffrey K. Hadden, Professor of Sociology, UVA • David G. Bromley, Professor of Sociology and Religious Studies, Virginia Commonwealth University • James T. Richardson, Professor of Sociology and Judicial Studies, University of Nevada • Gregory Saathoff, M.D. Associate Professor of Clinical Psychiatric Medicine, and Executive Director of the Critical Incident Analysis Group, UVA A presentation held on Friday, November 13, 1998 at The University of Virginia Sponsored by: The Critical Incident Analysis Group at the University of Virginia Department of Sociology, Department of Religious Studies UVA Continuing Education Center for Study of Mind and Human Interaction Apocalyptic Millennialism in the West:The Case of the Solar Temple Copyright © 1998 by the Rector and Board of Visitors of the University of Virginia Critical Incident Analysis Group 1 INTRODUCTION Gregory B. Saathoff, M.D. Executive Director, Critical Incident Analysis Group On November 13, 1998, the University of Virginia was pleased to host an important session that examined many issues surrounding the emergence of Apocalyptic Millenialism in the 1990s. This event was organized by the Critical Incident Analysis Group at the University of Virginia, and co-sponsored by the Departments of Religious Studies and Sociology, and by the Medical School’s Center for the Study of Mind and Human Interaction. As the year 2000 approaches, many groups with apocalyptic, violent, and even suicidal designs are becoming prominent in their preparations for catastrophic, millennial events. -

Reading the Book of Revelation Politically

start page: 339 Stellenbosch eological Journal 2017, Vol 3, No 2, 339–360 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.17570/stj.2017.v3n2.a15 Online ISSN 2413-9467 | Print ISSN 2413-9459 2017 © Pieter de Waal Neethling Trust Reading the Book of Revelation politically De Villiers, Pieter GR University of the Free State [email protected] Abstract In this essay the political use of Revelation in the first five centuries will be analysed in greatest detail, with some references to other examples. Focus will be on two trajectories of interpretation: literalist, eschatological readings and symbolic, spiritualizing interpretations of the text. Whilst the first approach reads the book as predictions of future events, the second approach links the text with spiritual themes and contents that do not refer to outstanding events in time and history. The essay will argue that both of these trajectories are ultimately determined by political considerations. In a final section, a contemporary reading of Revelation will be analysed in order to illustrate the continuing and important presence of political readings in the reception history of Revelation, albeit in new, unique forms. Key words Book of Revelation; eschatological; symbolic; spiritualizing; political considerations 1. Introduction Revelation is often associated with movements on the fringes of societies that are preoccupied with visions and calculations about the end time.1 The book has also been used throughout the centuries to reflect on and challenge political structures and 1 Cf. Barbara R. Rossing, The Rapture Exposed: the Message of Hope in the Book of Revelation (Westview Press, Boulder, CO., 2004). Robert Jewett, Jesus against the Rapture. -

Gog and Magog and Ethnic Difference in the Catalan Atlas (1375) Thomas Franke

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository History ETDs Electronic Theses and Dissertations 9-12-2014 Monsters at the End of Time: Gog and Magog and Ethnic Difference in the Catalan Atlas (1375) Thomas Franke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds Recommended Citation Franke, Thomas. "Monsters at the End of Time: Gog and Magog and Ethnic Difference in the Catalan Atlas (1375)." (2014). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/hist_etds/30 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Electronic Theses and Dissertations at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in History ETDs by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thomas Samuel Franke Candidate History Department This thesis is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication: Approved by the Thesis Committee: Michael A. Ryan , Chairperson Timothy C. Graham Sarah Davis-Secord Franke i MONSTERS AT THE END OF TIME: GOG AND MAGOG AND ETHNIC DIFFERENCE IN THE CATALAN ATLAS (1375) by THOMAS FRANKE BACHELOR OF ARTS, UC IRVINE 2012 THESIS Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS HISTORY The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico JULY 2014 Franke ii Abstract Franke, Thomas. Monsters at the End of Time: Gog and Magog and Ethnic Difference in the Catalan Atlas (1375). University of New Mexico, 2014. Although they are only mentioned briefly in Revelation, the destructive Gog and Magog formed an important component of apocalyptic thought for medieval European Christians, who associated Gog and Magog with a number of non-Christian peoples. -

Demystifying the Number of the Beast in the Book of Revelation: Examples of Ancient Cryptology and the Interpretation of the “666” Conundrum

University of Wollongong Research Online Faculty of Engineering and Information Faculty of Informatics - Papers (Archive) Sciences 2010 Demystifying the number of the beast in the book of revelation: examples of ancient cryptology and the interpretation of the “666” conundrum M G. Michael University of Wollongong, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/infopapers Part of the Physical Sciences and Mathematics Commons Recommended Citation Michael, M G.: Demystifying the number of the beast in the book of revelation: examples of ancient cryptology and the interpretation of the “666” conundrum 2010. https://ro.uow.edu.au/infopapers/3585 Research Online is the open access institutional repository for the University of Wollongong. For further information contact the UOW Library: [email protected] Demystifying the number of the beast in the book of revelation: examples of ancient cryptology and the interpretation of the “666” conundrum Abstract As the year 2000 came and went, with the suitably forecasted fuse-box of utopian and apocalyptic responses, the question of "666" (Rev 13:18) was once more brought to our attention in different ways. Biblical scholars, for instance, focused again on the interpretation of the notorious conundrum and on the Traditionsgeschichte of Antichrist. For some of those commentators it was a reply to the outpouring of sensationalist publications fuelled by the millennial mania. This paper aims to shed some light on the background, the sources, and the interpretation of the “number of the beast”. It explores the ancient techniques for understanding the conundrum including: gematria, arithmetic, symbolic, and riddle-based solutions. -

The Beast, the Whore, the Bride & the Groom

The Beast, The Whore, The Bride & The Groom Revelation 12-19 Revelation 12:1-6 The Woman & Dragon Act 2: After the Seventh Trumpet - Setting: Heaven moving to Earth. - The Woman with the Sun, Moon and Crown: Giving Birth (12:2) - The Red Dragon (Satan), with his tail he sweeps a third of the stars down from heaven. He opposes the Woman (12:3-4) - The Child: Identified as Jesus, was caught up to Heaven. The Woman Retreats into the wilderness. (12:5-6) Revelation 12:7-12 The Heavenly War Michael and His Angels declare war on the Dragon Satan is Cast Down with his minions Heaven Rejoices: “Now Salvation the of our Christ has come” Revelation 12:13-17 The Woman & The Dragon Part 2 The Dragon Pursues her and the earth aids the woman. The earth opens its mouth to swallow the water that the Dragon intends to destroy her with. The Dragon then pursues her children, attempting to make war with them. Discussion Question #1 Koester notes that the woman in labor should be understood as the people of God, and notes, “Christian readers might naturally identify her with Mary… By the end of the chapter, however, it becomes clear that the woman is the mother of all believers…” (123) Is this interpretation of the woman valid? Why or why not? Revelation 13: The Beasts ● The Beast from the Sea (13:1-10): 10 Horns and 7 Heads and 10 Diadems. It was worshipped, given authority to conquer and was utterly blasphemous. Everyone worshipped it except those who were found in the Book of Life. -

Lesson 7A FINAL (GENERAL Or LAST) JUDGMENT

Lesson 7A FINAL (GENERAL or LAST) JUDGMENT Beloved Father of Mercy and Justice, We Your children, offer our lives as a pure and holy sacrifice, uniting our lives and our death to the life and death of Your Son and our Savior. At the Final Judgment we will stand united with the Body of Christ, body and soul, to receive Your Son's judgment. We will face this last and definitive judgment unafraid as the Books of Works are opened to reveal the imperishable deeds of love and mercy accumulated by the Church. This is the treasure stored up for eternity which Your children offer in the name of Christ our Savior and Redeemer. Send Your Holy Spirit, Lord, to lead us in this lesson of our study on the Eight Last Things. We pray in the name of God the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Amen. + + + While I was watching thrones were set in place and one most venerable took his seat. His robe was white as snow, the hair of his head as pure as wool. His throne was a blaze of flames; its wheels were a burning fire. A stream of fire poured out, issuing from his presence. A thousand thousand waited on him, ten thousand times ten thousand stood before him. The court was in session and the books lay open. Daniel 7:9-10 For as the Father has life in himself, so he has granted the Son also to have life in himself; and, because he is the Son of man, has granted him power to give judgment.