Roads to Paradise

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

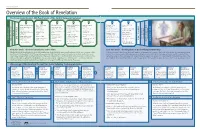

Overview of the Book of Revelation the Seven Seals (Seven 1,000-Year Periods of the Earth’S Temporal Existence)

NEW TESTAMENT Overview of the Book of Revelation The Seven Seals (Seven 1,000-Year Periods of the Earth’s Temporal Existence) 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Adam’s ministry began City of Enoch was Abraham’s ministry Israel was divided into John the Baptist’s Renaissance and Destruction of the translated two kingdoms ministry Reformation wicked Wickedness began to Isaac, Jacob, and spread Noah’s ministry twelve tribes of Israel Isaiah’s ministry Christ’s ministry Industrial Revolution Christ comes to reign as King of kings Repentance was Great Flood— Israel’s bondage in Ten tribes were taken Church was Joseph Smith’s ministry taught by prophets and mankind began Egypt captive established Earth receives Restored Church patriarchs again paradisiacal glory Moses’s ministry Judah was taken The Savior’s atoning becomes global CREATION Adam gathered and Tower of Babel captive, and temple sacrifice Satan is bound Conquest of land of Saints prepare for Christ EARTH’S DAY OF DAY EARTH’S blessed his children was destroyed OF DAY EARTH’S PROBATION ENDS PROBATION PROBATION ENDS PROBATION ETERNAL REWARD FALL OF ADAM FALL Jaredites traveled to Canaan Gospel was taken to Millennial era of peace ETERNAL REWARD ETERNITIES PAST Great calamities Great calamities FINAL JUDGMENT FINAL JUDGMENT PREMORTAL EXISTENCE PREMORTAL Adam died promised land Jews returned to the Gentiles and love and love ETERNITIES FUTURE Israelites began to ETERNITIES FUTURE ALL PEOPLE RECEIVE THEIR Jerusalem Zion established ALL PEOPLE RECEIVE THEIR Enoch’s ministry have kings Great Apostasy and Earth -

Fazlallah Astarabadi and the Hurufis

prelims.046 17/12/2004 4:58 PM Page i MAKERS of the MUSLIM WORLD Fazlallah Astarabadi and The Hurufis “Shahzad Bashir is to be commended for producing a remarkably accessible work on a complex subject; his explanations are models of lucidity and brevity.” PROFESSOR DEVIN DEWEESE, INDIANA UNIVERSITY prelims.046 14/12/2004 1:37 PM Page ii SELECTION OF TITLES IN THE MAKERS OF THE MUSLIM WORLD SERIES Series editor: Patricia Crone, Institute for Advanced Study,Princeton ‘Abd al-Malik, Chase F.Robinson Abd al-Rahman III, Maribel Fierro Abu Nuwas, Philip Kennedy Ahmad ibn Hanbal, Christopher Melchert Ahmad Riza Khan Barelwi, Usha Sanyal Al-Ma’mun, Michael Cooperson Al-Mutanabbi, Margaret Larkin Amir Khusraw, Sunil Sharma El Hajj Beshir Agha, Jane Hathaway Fazlallah Astarabadi and the Hurufis, Shazad Bashir Ibn ‘Arabi,William C. Chittick Ibn Fudi,Ahmad Dallal Ikhwan al-Safa, Godefroid de Callatay Shaykh Mufid,Tamima Bayhom-Daou For current information and details of other books in the series, please visit www.oneworld-publications.com/ subjects/makers-of-muslim-world.htm prelims.046 14/12/2004 1:37 PM Page iii MAKERS of the MUSLIM WORLD Fazlallah Astarabadi and The Hurufis SHAHZAD BASHIR prelims.046 14/12/2004 1:37 PM Page iv FAZLALLAH ASTARABADI AND THE HURUFIS Oneworld Publications (Sales and editorial) 185 Banbury Road Oxford OX2 7AR England www.oneworld-publications.com © Shahzad Bashir 2005 All rights reserved Copyright under Berne Convention A CIP record for this title is available from the British Library ISBN 1–85168–385–2 Typeset by Jayvee, -

Bur¯Aq Depicted As Amanita Muscaria in a 15Th Century Timurid-Illuminated Manuscript?

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Journal of Psychedelic Studies 3(2), pp. 133–141 (2019) DOI: 10.1556/2054.2019.023 First published online September 24, 2019 Bur¯aq depicted as Amanita muscaria in a 15th century Timurid-illuminated manuscript? ALAN PIPER* Independent Scholar, Newham, London, UK (Received: May 8, 2019; accepted: August 2, 2019) A series of illustrations in a 15th century Timurid manuscript record the mi’raj, the ascent through the seven heavens by Mohammed, the Prophet of Islam. Several of the illustrations depict Bur¯aq, the fabulous creature by means of which Mohammed achieves his ascent, with distinctive features of the Amanita muscaria mushroom. A. muscaria or “fly agaric” is a psychoactive mushroom used by Siberian shamans to enter the spirit world for the purposes of conversing with spirits or diagnosing and curing disease. Using an interdisciplinary approach, the author explores the routes by which Bur¯aq could have come to be depicted in this manuscript with the characteristics of a psychoactive fungus, when any suggestion that the Prophet might have had recourse to a drug to accomplish his spirit journey would be anathema to orthodox Islam. There is no suggestion that Mohammad’s night journey (isra) or ascent (mi’raj) was accomplished under the influence of a psychoactive mushroom or plant. Keywords: Mi’raj, Timurid, Central Asia, shamanism, Siberia, Amanita muscaria CULTURAL CONTEXT Bur¯aq depicted as Amanita muscaria in the mi’raj manscript The mi’raj manuscript In the Muslim tradition, the mi’raj was preceded by the isra or “Night Journey” during which Mohammed traveled An illustrated manuscript depicting, in a series of miniatures, overnight from Mecca to Jerusalem by means of a fabulous thesuccessivestagesofthemi’raj, the miraculous ascent of beast called Bur¯aq. -

Janna & Jahannam 05 September 2020

05 September 2020 Janna & Jahannam Objective: To know what Janna and Jahannam represent to Muslims. To explain how Allah decides where people go. Starter: Write all the bad things you’ve done today i.e. Not doing h/w; and all the good things you’ve done today i.e. holding a door open for someone. Tally them up- do you have more good/bad deeds? BWS God weighs our deeds • Muslims believe that God will Think back to weigh up our good and bad last lesson… deeds in life and this will What determine what happens to us constitutes a after death. good deed? • God judges our actions, but also our intentions (niyyah) BWS Munkar and Nakir • https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yH5TGtGiHsM •Who are Munkar and Nakir? •What is their role? •What questions do they ask? BWS Barzakh •Barzakh: A place of waiting, after death until the day of judgement. •For those who die before the day of judgement, the angel of death Azrail, will take their souls to wait in the state of barzakh until the sound of the final trumpet. BWS Janna ‘In paradise, I prepare for the • What might this tell us about righteous believers Janna? what no eye has • A state of joy, happiness and peace. ever seen…’ • A reward for living a good life. (Hadith) • Everything one longs for on earth, you will find in paradise. BWS Jahannam • A place of terror. • Physical torment as well as being separated from God. • Disbelievers and sinners will go here. BWS Important questions •Read the 3 questions. -

A Re-Examination of the Millennium in Rev 20:1–6: Consummation and Recapitulation

JETS 44/2 (June 2001) 237–51 A RE-EXAMINATION OF THE MILLENNIUM IN REV 20:1–6: CONSUMMATION AND RECAPITULATION dave mathewson* i. introduction The question of the so-called millennial kingdom in Rev 20:1–6 continues to be a source of fascination in evangelical discussion and dialogue.1 The purpose of this article is to re-examine the question of the millennial king- dom as articulated in Rev 20:1–6. More specifically, this article will consider the meaning and function of 20:1–6 within Revelation as it relates to the contemporary debate about whether this section is best understood within a premillennial or amillennial framework. Hermeneutically, most of the de- bate has centered around how literally the reference to the one thousand years in 20:1–6 should be taken and, more importantly, the relationship be- tween 20:1–6 and 19:11–21. Does the thousand year period in 20:1–6 re- fer to a more or less literal period of time?2 Or should it be understood more symbolically? Does 20:1–6 follow 19:11–21 chronologically, with the one thou- sand years featuring a Zwischenreich (premillennialism), or does the final battle in 20:7–10 recapitulate the battle in 19:11–21, with the reference to the one thousand years in 20:1–6 extending all the way back to the first coming of Christ (amillennialism)?3 * Dave Mathewson is instructor in New Testament at Oak Hills Christian College, 1600 Oak Hills Road SW, Bemidji, MN 56601. 1 Cf. R. -

The Role of Fitrah As an Element in the Personality of a Da’I in Achieving the Identity of a True Da’I

International Journal of Business and Social Science Vol. 3 No. 4 [Special Issue - February 2012] THE ROLE OF FITRAH AS AN ELEMENT IN THE PERSONALITY OF A DA’I IN ACHIEVING THE IDENTITY OF A TRUE DA’I Zaizul Ab. Rahman Jabatan Usuluddin dan Falsafah Islamic Studies Faculty Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Malaysia Abstract In the era of fast-paced development, a dā„ī is constantly faced with a variety of challenges as a result of globalization, among which are attacks on mentality headed and sponsored by other religious groups. A strong element of true fitrah (which translates as „disposition‟) is a critical requirement in dealing with these challenges by supplying oneself with knowledge, faith and good deeds. With these elements, a dā„ī can face the era of globalization that is so rife with tribulations. A dā„ī that has no true identity is an easy mark for exploitation by those with interest in doing so. Introduction Fitrah is a highly important factor in shaping the identity of a dā„ī who is capable of carrying out a successful mission in his da‟wah movements. A dā„ī who is not in possession of an element of fitrah that has been sown with the seeds of an untainted personality cannot face the trials he will encounter from the target audience of his da‟wah. This is especially so if a comparison is made to the missionaries of other religions such as Christianity, whose missions move systematically and with detailed planning. Fitrah in Developing the Personality of a Dā‘ī In Islam, “tendency” may bear similarity to the term “fitrah”. -

Heaven in the Early History of Western Religions

Alison Joanne GREIG University of Wales Trinity Saint David MA in Cultural Astronomy and Astrology Module Name: Dissertation Module Code: AHAH7001 Alison Joanne Greig Student No. 27001842 31 December 2012 Heaven in the early history of Western religions Chapter 1 Approaches to concepts of heaven This dissertation examines concepts of heaven in the early history of Western religions and the extent to which themes found in other traditions are found in Christianity. Russell, in A History of Heaven, investigates the origins of the concept of heaven, which he dates at about 200 B.C.E. and observes that heaven, a concept that has shaped much of Christian thought and attitudes, has been strangely neglected by modern historians.1 Christianity has played a central role in Western civilization and instructs its believers to direct their life in this world with a view to achieving eternal life in the next, as observed by Liebeschuetz. 2 It is of the greatest historical importance that a very large number of people could for many centuries be persuaded to see life in an imperfect visible world as merely a stage in their progress to a world that was perfect but invisible; yet, it has been neglected as a subject for study. Russell notes that Heaven: A History3 by McDannell and Lang mainly offers sociological insights.4 Russell holds that the most important aspects of the concept of heaven are the beatific vision and the mystical union.5 Heaven, he says, is the state of being in 1 Jeffrey Burton Russell, A History of Heaven – The Singing Silence (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1997) xiii, xiv. -

An Inquiry Into How Some Muslims and Hindus in Indonesia Relate to Death

An Inquiry into how some Muslims and Hindus in Indonesia Relate to Death EVA ELANA SALTVEDT APPLETON SUPERVISOR Levi Geir Eidhamar Sissel Undheim University of Agder, 2020 Faculty of humanities and pedagogics Department of religion, philosophy and history Doctor, Doctor shall I die? Yes, my child, and so shall I. Rhyme by unknown author 2 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................... 5 METHOD ...................................................................................................................... 7 THE EMPIRICAL DATA ..................................................................................................... 7 MOST-SIMILAR SYSTEM DESIGN .................................................................................. 8 LANGUAGE CHALLENGES .............................................................................................. 8 DATA SAMPLING ............................................................................................................... 9 INTERVIEW STRUCTURE ............................................................................................... 10 ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS ......................................................................................... 10 GROUNDED THEORY ...................................................................................................... 13 METHODOLOGICAL CHALLENGES ............................................................................. 15 THE RELIGIOUS -

Lesson 7A FINAL (GENERAL Or LAST) JUDGMENT

Lesson 7A FINAL (GENERAL or LAST) JUDGMENT Beloved Father of Mercy and Justice, We Your children, offer our lives as a pure and holy sacrifice, uniting our lives and our death to the life and death of Your Son and our Savior. At the Final Judgment we will stand united with the Body of Christ, body and soul, to receive Your Son's judgment. We will face this last and definitive judgment unafraid as the Books of Works are opened to reveal the imperishable deeds of love and mercy accumulated by the Church. This is the treasure stored up for eternity which Your children offer in the name of Christ our Savior and Redeemer. Send Your Holy Spirit, Lord, to lead us in this lesson of our study on the Eight Last Things. We pray in the name of God the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. Amen. + + + While I was watching thrones were set in place and one most venerable took his seat. His robe was white as snow, the hair of his head as pure as wool. His throne was a blaze of flames; its wheels were a burning fire. A stream of fire poured out, issuing from his presence. A thousand thousand waited on him, ten thousand times ten thousand stood before him. The court was in session and the books lay open. Daniel 7:9-10 For as the Father has life in himself, so he has granted the Son also to have life in himself; and, because he is the Son of man, has granted him power to give judgment. -

The Barzakh of Flamenco: Tracing the Spirituality, Locality and Musicality of Flamenco from South of the Strait of Gibraltar

SIT Graduate Institute/SIT Study Abroad SIT Digital Collections Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection SIT Study Abroad Fall 2011 The aB rzakh of Flamenco: Tracing the Spirituality, Locality and Musicality of Flamenco From South of the Strait of Gibraltar Tania Flores SIT Study Abroad Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection Part of the Dance Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, and the Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons Recommended Citation Flores, Tania, "The aB rzakh of Flamenco: Tracing the Spirituality, Locality and Musicality of Flamenco From South of the Strait of Gibraltar" (2011). Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection. 1118. https://digitalcollections.sit.edu/isp_collection/1118 This Unpublished Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the SIT Study Abroad at SIT Digital Collections. It has been accepted for inclusion in Independent Study Project (ISP) Collection by an authorized administrator of SIT Digital Collections. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Barzakh of Flamenco: Tracing the Spirituality, Locality and Musicality of Flamenco from South of the Strait of Gibraltar Tania Flores Occidental College Migration and Transnational Identity: Fall 2011 Flores 2 Acknowledgments I could not have completed this project without the advice and guidance of my academic director, Professor Souad Eddouada; my advisor, Professor Taieb Belghazi; my professor of music at Occidental College, Professor Simeon Pillich; my professor of Islamic studies at Occidental, Professor Malek Moazzam-Doulat; or my gracious and helpful interviewees. I am also grateful to Elvira Roca Rey for allowing me to use her studio to choreograph after we had finished dance class, and to Professor Said Graiouid for his guidance and time. -

Amillennialism Reconsidered Beatrices

Andrews University Seminary Studies, Vol. 43, No. 1,185-210. Copyright 0 2005 Andrews University Press. AMILLENNIALISM RECONSIDERED BEATRICES. NEALL Union College Lincoln, Nebraska Introduction G. K. Beale's latest commentary on Revelation and Kim Riddlebarger's new book A Casefor Ami~~ennialismhave renewed interest in the debate on the nature of the millennium.' Amillennialism has an illustrious history of support from Augustine, theologians of the Calvinistic and ~utheran confessions, and a long line of Reformed theologians such as Abraham Kuyper, Amin Vos, H. Ridderbos, A. A. Hoekema, and M. G. line? Amillennialists recognize that a straightforward reading of the text seems to show "the chronologicalp'ogression of Rev 19-20, the futurity of Satan's imprisonment,the physicality of 'the first resurrection' and the literalness of the one thousand years" (emphasis supplied).) However, they do not accept a chronologicalprogression of the events in these chapters, preferring instead to understand the events as recapitulatory. Their rejection of the natural reading of the text is driven by a hermeneutic of strong inaugurated eschatology4-the paradox that in the Apocalypse divine victory over the dragon and the reign of Christ and his church over this present evil world consist in participating with Christ in his sufferings and death? Inaugurated eschatology emphasizes Jesus' victory over the powers of evil at the cross. Since that monumental event, described so dramatically in Rev 12, Satan has been bound and the saints have been reigning (Rev 20). From the strong connection between the two chapters (see Table 1 below) they infer that Rev 20 recapitulates Rev 12. -

Islam in Process—Historical and Civilizational Perspectives Yearbook of the Sociology of Islam Volume 7

Islam in Process—Historical and Civilizational Perspectives Yearbook of the Sociology of Islam Volume 7 2006-12-06 16-23-03 --- Projekt: T491.gli.arnason.yearbook7 / Dokument: FAX ID 00fb133402603594|(S. 1 ) T00_01 Schmutztitel.p 133402603618 Yearbook of the Sociology of Islam Edited by Georg Stauth and Armando Salvatore The Yearbook of the Sociology of Islam investigates the making of Islam into an important component of modern society and cultural globalization. Sociology is, by common consent, the most ambitious advocate of modern society. In other words, it undertakes to develop an understanding of modern existence in terms of breakthroughs from ancient cosmological cultures to ordered and plural civic life based on the gradual subsiding of communal life. Thus, within this undertaking, the sociological project of modernity figures as the cultural machine that dislodges the rationale of social being from local, communal, hierarchic contexts into the logic of individualism and social differentiation. The conventional wisdom of sociology has been challenged by post-modern debate, abolishing this dichotomous evolutionism while embracing a more heterogeneous view of coexistence and exchange between local cultures and modern institutions. Islam, however, is often described as a different cultural machine for the holistic reproduction of pre-modern religion, and Muslims are seen as community-bound social actors embodying a powerful potential for the rejec- tion of and opposition to Western modernity. Sociologists insist on looking for social differentiation and cultural differ- ences. However, their concepts remain evolutionist and inherently tied to the cultural machine of modernity. The Yearbook of the Sociology of Islam takes these antinomies and contradic- tions as a challenge.